Abstract

Most poverty studies build on measures that take account of recurring incomes from sources such as labour or social transfers. However, other financial resources such as savings and assets also affect living standards, often in very significant ways. Previous studies that have sought to incorporate assets into poverty measures agree that (1) poverty estimates including wealth are considerably lower than the traditional income-based measures; (2) poverty rates of the elderly are more affected than those of the non-elderly and (3) poverty rates are especially affected by the household’s main residence. This paper assesses the sensitivity of these conclusions to various plausible alternative assumptions, such as the poverty line calculation, the types of assets included in the wealth concept and choices with respect to the equivalence scale. Moreover, we check whether the impact of alternative assumptions is consistent across age and institutional settings. To that effect we compare Belgium and Germany, two countries with similar living standards and income poverty rates, but very different levels and distributions of wealth. Using data from the Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey we show that accounting for wealth affects the incidence and age structure of poverty in a very substantial way. However, we also illustrate that results strongly depend on all kinds of measurement choices. We show that poverty rates may increase as well as decrease depending on how wealth is accounted for. Cross-country rankings may also change, overall or for specific groups. Second, current measures are not representative for young households such that any conclusion on the age ratio of poverty is highly sensitive to the assumptions made.

Source: Brandolini et al. (2010, pp. 270, 272)

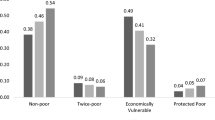

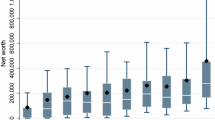

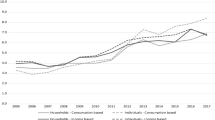

Source: own calculations based on HFCS

Source: own calculations based on HFCS

Source: own calculations based on HFCS

Source: own calculations based on HFCS

Source: own calculations based on HFCS

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It should be clear that not all asset types can be easily sold or bought on the market. In the case of non-liquid assets like real estate it is certain that an immediate sale would mean incurring substantial costs.

The specification of n in function of expected lifetimes of both partners is proposed by Rendall and Speare (1993). Although Brandolini et al. (2010) discuss this broader specification, they do not implement it. As most authors they use the longest of the two expected lifetimes. We prefer to use the Rendall and Speare specification because it represents the improved economic situation of the surviving household as the same level of wealth is then available to fulfill the needs of fewer household members. Ideally, one should take into account the wealth loss due to inheritance taxes.

Authors tend to refer to wealth poverty when implementing the unidimensional approach, while the term asset poverty is mostly used for the two-dimensional approach. As both approaches use net worth in their calculations, this reflects only a difference in terminology.

In Belgium this oversampling was based on the NUTS 1 region and the average income by neighbourhood of residence.

Property taxes could not be taken into account because the HFCS does not include cadastral values.

A Eurostat study (2013) proposes another method to jointly assess poverty in disposable income and net wealth. By statistically matching the EU-SILC and HFCS data they largely find the same results.

Also saved income from the ongoing year can be represented in the net worth measure. As we have no information on current incomes we cannot correct for this.

We cannot assign life expectancies if we do not have information on the exact age. As a consequence for both countries about 80 sample households were not included in the analysis.

Elderly is defined as at least one of the adults being 65 years or older, the legal retirement age in Belgium and Germany.

It is also possible to use broader wealth concepts. For example, augmented wealth will add to disposable wealth some valuation of pension rights and human capital or a comparable measure of future earnings possibilities (Wolff 1990). However, since this kind of information is not covered in the HFCS data, we do not implement such a wider wealth concept.

θ equal to 0.5 refers to the square root equivalence scale, which is used in the baseline indicators.

If wealth is annuitized over an infinite period it would be equal to the traditional income poverty indicator.

Weisbrod and Hansen (1968) argue: “the fact that intergenerational transfers are so frequently made via the estate route rather than by transfers before death may be less an indication of people’s desires to pass on their wealth than it is a reflection of their inability to anticipate the time of their death.” Indeed, if people were to know exactly when they would die, they would transfer their wealth before death so as to avoid inheritance taxes.

This is not only true for the joint income-wealth poverty measures; equivalence scales also have the largest impact on the elderly in terms of traditional income poverty (e.g. de Vos and Zaidi 1997).

References

Almås, I., & Mogstad, M. (2012). Older or wealthier? The impact of age adjustment on wealth inequality. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 114(1), 24–54.

Aratani, Y., & Chau, M. (2010). Asset poverty and debt among families with children. New York: National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

Arrondel, L., Roger, M., & Savignac, F. (2014). Wealth and income in the Euro area. Heterogeneity in households’ behaviours? ECB working paper no. 1709.

Atkinson, A. B. (1971). The distribution of wealth and the individual life-cycle. Oxford Economic Papers, 23(2), 239–254.

Azpitarte, F. (2011). Measurement and identification of asset poor households: A cross-national comparison of Spain and the United Kingdom. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(1), 87–110.

Azpitarte, F. (2012). Measuring poverty using both income and wealth: A cross-country comparison between the U.S. and Spain. Review of Income and Wealth, 58(1), 24–50.

Bernheim, B. D., Shleifer, A., & Summers, L. H. (1985). The strategic bequest motive. Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1045–1076.

Beverly, S., Sherraden, M., Cramer, R., Williams, T. R., Nam, Y., & Zhan, M. (2008). Determinants of asset holdings. In S.-M. McKernan & M. Sherraden (Eds.), Asset building and low-income families (pp. 89–151). Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press.

Brandolini, A., Magri, S., & Smeeding, T. (2010). Asset-based measurement of poverty. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29(2), 267–284.

Bucks, B. (2011). Economic vulnerability in the United States: Measurement and trends. Paper prepared for the IARIW-OECD conference on economic insecurity, Paris, France, 22–23 November 2011.

Buhmann, B., Rainwater, L., Schmaus, G., & Smeeding, T. (1988). Equivalence scales, well-being, inequality, and poverty: Sensitivity estimates across ten countries using the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) database. Review of Income and Wealth, 34(2), 115–142.

Canberra Group. (2011). Canberra Group handbook on household income statistics (2nd ed.). Geneva: United Nations.

Caner, A., & Wolff, E. N. (2004). Asset poverty in the United States, 1984–99: Evidence from the panel study of income dynamics. Review of Income and Wealth, 50(4), 493–518.

Coulter, F., Cowell, F., & Jenkins, S. (1992). Equivalence scale relativities and the extent of inequality and poverty. Economic Journal, 102(414), 1067–1082.

Cowell, F., & Van Kerm, P. (2015). Wealth inequality: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(4), 671–710.

Cremer, H., & Pestieau, P. (2006). Wealth transfer taxation: A survey of the theoretical literature. In S. C. Kolm & J. Mercier Ythier (Eds.), Handbook on altruism, giving and reciprocity (Vol. 2, pp. 1108–1134). Amsterdam: North Holland.

D’Ambrosio, C., Frick, J. R., & Jäntti, M. (2009). Satisfaction with life and economic well-being: Evidence from Germany. Schmollers Jahrbuch: Journal of Applied Social Science Studies/Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften, 192(2), 283–295.

Davies, J. B., Sandström, S., Shorrocks, A., & Wolff, E. N. (2011). The level and distribution of global household wealth. The Economic Journal, 121(551), 223–254.

De Decker, P. (2011). Understanding housing sprawl: The case of Flanders, Belgium. Environment and Planning Part A, 43(7), 1634–1654.

De Decker, P., & Dewilde, C. (2010). Home-ownership and asset-based welfare: The case of Belgium. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(2), 243–262.

de Vos, K., & Zaidi, A. (1997). Equivalence scale sensitivity of poverty statistics for the member states of the European Community. Review of Income and Wealth, 43(3), 319–333.

Directorate-General Statistics, Department Economics of the Belgian Federal Government. (2014). Sterftetafels jaarlijks in exacte leeftijd (1994–2012). Retrieved June 19, 2014 from http://statbel.fgiv.be/nl/modules/publications/statistiques/bevolking/downloads/bevolking_sterftetafels.jsp

European Central Bank. (n.d.). (2013). European Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS) wave 1. Retrieved from https://www.ecb.europa.eu/secure/hfcs/login.html

Eurostat. (2013). Data matching—Final report ESTAT study. Case study on income and wealth (SILC-HFCS). Document LC-LEGAL/19/13 presented at the 7th meeting of the Task force on the revision of the EU-SILC legal basis 5–6 December 2013.

Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Network. (2013a). The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey—Methodological report for the first wave. ECB statistics paper no. 1

Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Network. (2013b). The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey—Results from the first wave. ECB statistics paper no. 2

Haveman, R., & Wolff, E. N. (2004). The concept and measurement of asset poverty: Levels, trends and composition for the U.S., 1983–2001. Journal of Economic Inequality, 2(2), 145–169.

Headey, B. (2008). Poverty is low consumption and low wealth, not just low income. Social Indicators Research, 89(1), 23–39.

Headey, B., & Wooden, M. (2004). The effects of wealth and income on subjective well-being and ill-being. The Economic Record, 80(S1), S24–S33.

Jäntti, M., Sierminska, E., & Van Kerm, P. (2013). The joint distribution of income and wealth. In J. C. Gornick & M. Jäntti (Eds.), Income inequality. Economic disparities and the middle class in affluent countries (pp. 312–333). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Jappelli, T., & Padula, M. (2013). Investment in financial literacy and saving decisions. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(8), 2779–2792.

Kim, K. S., & Kim, Y. M. (2013). Asset poverty in Korea: Levels and composition based on Wolff’s definition. International Journal of Social Welfare, 22(2), 175–185.

Kopczuk, W., & Lupton, J. P. (2007). To leave or not to leave: The distribution of bequest motives. Review of Economic Studies, 74(1), 207–235.

Kuypers, S., Figari, F., & Verbist, G. (2015). Improving the incorporation of wealth information in data for policy analysis. Converting the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS) for microsimulation purposes. Paper prepared for the 5th general conference of the International Microsimulation Association (IMA) 2–4 September 2015, Luxembourg.

Lerman, D. L., & Mikesell, J. J. (1988). Impacts of adding net worth to the poverty definition. Eastern Economic Journal, 15(2), 357–370.

Mattonetti, M. (2013). European household income by groups of households. Eurostat methodologies and working papers.

McKernan, S.-M., Ratcliffe, C., & Williams Shanks, T. (2012). Is poverty incompatible with asset accumulation? In P. N. Jefferson (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the economics of poverty (pp. 463–493). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Milanovic, B. (2006). Global income inequality: What it is and why it matters. World Bank Policy Research working paper 3865.

Nam, Y., Huang, J., & Sherraden, M. (2008). Asset definitions. In S.-M. McKernan & M. Sherraden (Eds.), Asset building and low-income families (pp. 1–31). Washington: The Urban Institute Press.

OECD. (2008). Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013a). OECD guidelines for micro statistics on household wealth. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013b). OECD framework for statistics on the distribution of household income, consumption and wealth. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2014). OECD employment outlook 2014. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Radner, D. B. (1990). Assessing the economic status of the aged and nonaged using alternative income-wealth measures. Social Security Bulletin March, 53(3), 2–14.

Rendall, M. S., & Speare, A. (1993). Comparing economic well-being among elderly Americans. Review if Income and Wealth, 39(1), 1–21.

Sen, A. (1985). Commodities and capabilties. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Sen, A. (1997). From income inequality to economic inequality. Southern Economic Journal, 64(2), 384–401.

Shefrin, H. M., & Thaler, R. H. (1992). Mental accounting, saving, and self-control. In G. Loewenstein & J. Elster (Eds.), Choice over time (pp. 287–330). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sherraden, M. W. (1991). Assets and the poor: A new American welfare policy. New York: M.E. Sharpe Inc.

Short, K., & Ruggles, P. (2005). Experimental measures of poverty and net worth: 1996. Journal of Income Distribution Special Issue on Assest and Poverty, 13(3–4), 8–21.

Skopek, N., Kolb, K., Buchholz, S., & Blossfeld, H. P. (2012). Income rich–asset poor? The composition of wealth and the meaning of different wealth components in a European comparison. Berliner Journal für Soziologie, 22(2), 163–187.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2012). Periodensterbetafeln für Deutschland.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress.

Sullivan, J. X. (2008). Borrowing during unemployment: Unsecured debt as a safety net. Journal of Human Resources, 43(2), 383–412.

Szydlik, M. (2011). Inheritance in Europe. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 63(4), 543–565.

Thaler, R. H. (1990). Saving, fungibility and mental accounts. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(1), 193–205.

Törmälehto, V.-M., Kannas, O., & Säylä, M. (2013). Integrated measurement of household-level income, wealth and non-monetary well-being in Finland. Statistics Finland working paper.

Van den Bosch, K. (1998). Poverty and assets in Belgium. Review of Income and Wealth, 44(2), 215–228.

Vuchelen, J. (1991). De beleggingen van de Belgische gezinnen, 1960–88 (The investments of Belgian households, 1960–88). Brussels Economic Review, 130, 189–217.

Wagner, G., & Grabka, M. (1999). Robustness assessment report (RAR) socio-economic panel 1984–1998. Berlin: German Socio-Economic Panel.

Weisbrod, B. A., & Hansen, W. L. (1968). An income-net worth approach to measuring economic welfare. American Economic Review, 58(5), 1315–1329.

Wolff, E. N. (1990). Methodological issues in the estimation of the size distribution of household wealth. Journal of Econometrics, 25(2), 179–195.

Zagorsky, J. L. (2005). Measuring poverty using both income and wealth. Journal of Income Distribution Special Issue on Assets and Poverty, 13(3–4), 22–40.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Belgian Science Policy Office (BELSPO) under contract BR/121/A5/CRESUS. We would like to thank Koen Decancq, Gerlinde Verbist and participants of the 2015 Spring Meeting of the ISA RC28, the 2015 LISER/DSEF Joint PhD Workshop, the 2016 Improve Final conference and 34th IARIW General Conference 2016 for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuypers, S., Marx, I. Estimation of Joint Income-Wealth Poverty: A Sensitivity Analysis. Soc Indic Res 136, 117–137 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1529-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1529-5