Abstract

Since the 1960s, public support for gender egalitarianism has risen substantially in many western countries. Although earlier research proposed that structural and cultural developments, such as educational expansion, declining religiosity, and the rise of women’s employment may explain this upward trend, these theoretical speculations have not yet been thoroughly tested. In the present research, we aim to contribute to the existing literature by empirically analyzing the influence of educational expansion, secularization, and the rise of women’s labor force participation on support for gender egalitarianism in the Netherlands and to explore to what extent these influences differ for men and women. We use repeated cross-sectional survey data from the Netherlands involving 12,146 men and 13,858 women. To capture cohort and period effects, we include historical and contemporary contextual measures of educational expansion, secularization, and female labor force participation obtained from population censuses and labor force surveys, covering about 100 birth cohorts and 25 survey years. Of these three indicators, educational expansion contributed most to the rise in men’s, and particularly women’s, support for gender egalitarianism by changing the normative societal climate in which men and women have grown up and live. Promoting educational levels may therefore have far-reaching benefits for gender equality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Although gender equality has improved throughout the world, considerable gender-based inequality, discrimination, and exclusion persist (World Economic Forum 2015). Public support for gender egalitarianism may be an important factor in achieving gender equality because it contributes to a more egalitarian division of work and family responsibilities between partners, and it increases women’s opportunities, political participation, and labor market outcomes (Corrigall and Konrad 2007; Fortin 2005; Inglehart and Norris 2003). Gender egalitarianism is referred to as a belief system that supports equal rights, roles, and responsibilities for men and women and, vice versa, opposes the notion that men and women have innately different roles (i.e., women would essentially be more suited for caretaking and homemaking whereas men’s natural role is that of the breadwinner) (Davis and Greenstein 2009). Since the 1960s, a liberalizing trend toward greater public support for gender egalitarianism has been found in a wide range of countries, including the United States (Cotter et al. 2011; Mason and Lu 1988; Thornton et al. 1983), western Europe (Kraaykamp 2012; Lee et al. 2007; Scott et al. 1996), Australia (Van Egmond et al. 2010), as well as non-western countries (Inglehart and Norris 2003).

Theoretically, it is argued that structural and cultural developments, such as increasing levels of education, declining religiosity, the rise of women’s employment, declining fertility, and the women’s movement have propelled support for gender egalitarianism (Brewster and Padavic 2000; Cotter et al. 2011; Mason and Lu 1988; Pampel 2011; Scott et al. 1996; Shorrocks 2016). These developments have supposedly transformed the dominant societal discourse, exposing all individuals, and particularly those in late adolescence and early adulthood (the so-called “impressionable years”; Sears 1983, p. 81), to ideas of gender egalitarianism (Inglehart and Norris 2003). Instead, to explain the upward trend in support for gender egalitarianism, previous research has mainly compared levels of support for gender egalitarianism over time and across different birth cohorts (so-called period and cohort effects, respectively) (Brewster and Padavic 2000; Brooks and Bolzendahl 2004; Cotter et al. 2011; Firebaugh 1992; Kraaykamp 2012; Mason and Lu 1988; Neve 1995; Thijs et al. 2017). However, by using temporal measures of birth cohort and survey year as broad indicators of historical and contemporary societal developments, these studies leave unexplained why people living and growing up in times of different structural and cultural circumstances vary in their support for gender egalitarianism. In their literature review, Davis and Greenstein (2009, p. 91) concluded that “several researchers have found period effects, but the impetus for change continues to be unclear.” Thus, still surprisingly little is known about the underlying determinants of the overall upward trend in support for gender egalitarianism in the past decennia.

More recently, scholarly attention has been directed to an apparent slowdown of the trend toward gender egalitarianism in the mid-1990s, also referred to as the stalled gender revolution (Cotter et al. 2011; England 2010, p. 149–150; Pepin and Cotter 2018, p. 7; Shu and Meagher 2017, p. 1). Since then, studies have started to take the societal context into account to explain this stall in gender egalitarianism. For example, Shu and Meagher (2017) found that increased gender equality in the labor force partly accounted for the increase in gender attitudes in the United States in the 1980s, whereas the rise of men’s overwork appeared to explain part of the slowdown in gender attitudes in the 1990s as well as a restart of liberal gender attitudes from 2004 onwards. Pepin and Cotter (2018), by contrast, found that contextual increases in mothers’ education and employment played a minimal role in explaining American high school students’ gender attitudes about work and family. Based on cross-national comparisons, Dotti Sani and Quaranta (2017) found that adolescents’ gender attitudes are influenced by the dominant societal discourse on gender inequality, but it remains to be seen whether this persists over the lifecourse. To our knowledge, however, no prior study has as yet tested the influence of important structural and cultural developments in the societal context during people’s early adulthood on the upward trend in public support for gender egalitarianism.

In the present research, we aim to contribute to the existing literature on changes in gender egalitarianism by empirically analyzing the influence of three theoretically relevant societal developments—educational expansion, secularization, and the rise of women’s labor force participation—on support for gender egalitarianism among women and men in the Netherlands. Instead of estimating the influence of birth cohort and survey year to capture cohort and period effects as has been done in previous research, we analyze the influence of contextual measures of these three societal developments (a) when the respondents were in their late adolescence and early adulthood (16–20 years-old), and (b) in times of the survey year, while controlling for age effects and differences in the composition of the population. We thereby provide a more thorough test of the previously theorized influence of educational expansion, secularization, and female labor force participation on changes in gender egalitarianism over time and across cohorts (Menard 1991; Rodgers 1990). In addition, we analyze whether the influence of these structural and cultural developments is gendered because men and women have different interests in gender equality and may respond differently to questions about gender egalitarianism (Ciabattari 2001; Jennings 2006).

In the Netherlands, public support for gender egalitarianism has risen substantially to one of the highest levels in Europe (Merens and Van den Brakel 2014). Notwithstanding, views on childcare arrangements and responsibilities seem more ambivalent because women are still being held primarily responsible for their children and they spend more time on caregiving than men do (Knijn 1994; Merens and Van den Brakel 2014; Wiesmann et al. 2008). We therefore focus on one aspect of support for gender egalitarianism that seems of particular interest in the Netherlands as well as in many other western countries: whether women are viewed as more suited to raise little children than men are. Moreover, the Netherlands provides an interesting case because the Dutch societal and cultural context has vastly changed since the 1960s. As compared to many other countries, the Netherlands has been in the vanguard of educational expansion (Bar Haim and Shavit 2013) and secularization (Becker and De Hart 2006). In addition, Dutch women’s labor force participation has increased rapidly, shifting from one of the lowest in Europe to one of the highest in only a few decades, notwithstanding that the majority of women works part-time (Merens and Van den Brakel 2014; Pott-Buter 1993). Although other explanations for trends toward gender egalitarianism have been proposed in the literature, such as declining fertility or the women’s movement, we focus on these three developments because these have been very pervasive in the Netherlands. The Dutch women’s movement has been relatively small as compared to the United States. Moreover, we lack historical data on these contextual indicators during respondents’ emerging adulthood, and developments such as the women’s movement are difficult to operationalize in terms of numbers and impact.

We address the following research question: To what extent have historical and contemporary contextual indicators of educational expansion, secularization, and female labor force participation contributed to the trend toward stronger support for gender egalitarianism among men and women in the Netherlands since 1979? We use nationally representative cross-sectional data from the Cultural Changes in the Netherlands surveys between 1979 and 2006. We complement these data with historical and contemporary indicators of educational expansion, secularization, and female labor force participation collected from the Dutch population censuses and labor force surveys, covering a timespan of about 100 cohort years and about 25 survey years.

From Micro-Level Theories to Macro-Level Explanations

Two theoretical approaches are mainly used to explain individual variation in support for gender egalitarianism: the interest-based approach and the socialization or exposure approach. The interest-based perspective argues that people adopt and maintain attitudes that are in line with their personal goals and interests (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004). According to theories of socialization and exposure, people adopt egalitarian beliefs when socialized into liberal gender norms or when exposed to egalitarian ideas about gender (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004; Inglehart and Norris 2003). These perspectives are often employed to explain why women support gender egalitarianism more than men do (Davis and Greenstein 2009). Because women in general continue to have a deprived position in society as compared to men (Epstein 2007; World Economic Forum 2015), promoting gender equality benefits their interests (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004). Men, by contrast, gain less from supporting gender egalitarianism because it may undermine their dominant position or because they are simply unaware of their favorable position (Baxter and Kane 1995; Ciabattari 2001). In addition, childhood socialization in and exposure to egalitarian ideas and contexts are supposed to impact women more than men (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004; Dotti Sani and Quaranta 2017), resulting in stronger support for gender egalitarianism among women.

These individual-level theoretical perspectives, however, cannot explain changes in support for gender egalitarianism over time. Previous studies have therefore argued that people’s interest in and exposure to gender egalitarianism may have changed due to societal developments that have taken place during the past decades. For example, it is argued that women’s interest in gender egalitarianism in society has increased due to their rising educational levels, declining religiosity, and increasing labor market participation, which makes them more likely to adopt gender egalitarian views (Brooks and Bolzendahl 2004; Pampel 2011). Yet, the influence of these societal developments may even spill over to other individuals by shifting the normative climate to which all individuals, including men, are exposed (Inglehart and Norris 2003).

Historical and Contemporary Societal Developments

Building on theories of social change, societal developments could have influenced support for gender egalitarianism in two ways. First, according to theories of socialization, historical circumstances and events that people experience during late adolescence and early adulthood shape their basic values, attitudes, and worldviews (Jennings and Niemi 1981; Krosnick and Alwin 1989; Mannheim 1952; Sears 1983). It is argued that this period between late adolescence and early adulthood, also referred to as emerging adulthood (Arnett 2000), is a crucial period in people’s lives in which they are especially impressionable to the social and political context (Jennings and Niemi 1981; Krosnick and Alwin 1989). According to Mannheim (1952), people who share the same year of birth experience similar societal circumstances during their impressionable years. These so-called cohort effects are supposed to have a lasting influence on people’s attitudes throughout the lifecourse (Alwin and McCammon 2003; Inglehart 1997; Jennings and Niemi 1981; Krosnick and Alwin 1989; Sears 1983). People who are socialized under societal circumstances in which egalitarian gender norms prevail may therefore show more support for gender egalitarianism, even at later stages in their lives. Social change then originates from the natural replacement of older cohorts by younger cohorts with different experiences and, therefore, different attitudes (Mannheim 1952; Ryder 1965).

A second explanation assumes that people are open to change throughout the lifecourse and that they alter their attitudes in response to certain events and developments (Alwin and McCammon 2003). Contemporary societal circumstances at a certain moment in time, also referred to as period effects, may expose the entire population equally and simultaneously to a certain cultural discourse of gender egalitarianism, resulting in a broad shift in aggregate support for gender egalitarianism from one period to another (Inglehart and Norris 2003). Drawing on these theoretical notions of socialization and exposure, we derive predictions on cohort- and period-specific societal developments in the Netherlands that may have contributed to the upward trend toward gender egalitarianism.

Given the greater interest of women in supporting gender egalitarianism due to their relatively disadvantaged position, as well as their supposedly stronger socialization in and exposure to more egalitarian beliefs (Brooks and Bolzendahl 2004), we expect the influence of these societal circumstances to be consistently stronger for women as compared to men. Adopting egalitarian gender norms could benefit women’s educational and occupational opportunities and may reduce the double burden of paid labor and family responsibilities that women often experience (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004; Van der Lippe and Van Dijk 2001). For example, Dotti Sani and Quaranta (2017) found that the dominant societal discourse on gender equality had a strong influence on young women’s gender egalitarianism, but not on young men’s.

Educational Expansion

The educational level of the Dutch population has increased substantially in the last century (Bar Haim and Shavit 2013). It is argued that education has a liberalizing influence, transmitting ideas about diversity and equality, countering gender stereotypes, and increasing individuals’ openness to alternative perspectives on the roles of women and men in the public and private spheres (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004; Vogt 1997). Previous research has consistently shown that obtaining a higher educational level is related to more support for gender egalitarianism (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004; Brewster and Padavic 2000). When educational levels rise in society, the likelihood of interacting with people who endorse more egalitarian gender attitudes increases. Moreover, educational expansion may shift the dominant societal discourse regarding gendered roles, signaling a culture shift toward more opportunities for women. As a consequence, people in their emerging adult years have become socialized into an increasingly egalitarian societal context, instilling stronger support for gender egalitarianism in these cohorts. Although Pepin and Cotter (2018) found that contextual increases in mother’s educational levels in the United States played a minimal role in explaining changes in adolescents’ gender attitudes, a stronger influence of rising educational levels may be found when comparing gender egalitarianism across a larger number of generations. Hence, we propose that the higher the level of education in society to which people are exposed during emerging adulthood, the stronger people will support gender egalitarianism, and this cohort effect will be stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 1a).

Contemporary exposure to a highly educated societal context, characterized by a more egalitarian discourse, may also spill over to other individuals in such contexts, inducing support for gender egalitarianism among these individuals regardless of their own social position. For example, Banaszak and Plutzer (1993) found stronger support for gender egalitarianism in U.S. regions where women’s educational attainment approached that of men. To investigate whether this also applies when comparing different time points instead of regions, we formulate the following hypothesis: The higher the level of education to which people are exposed at a specific historical moment in time, the stronger people will support gender egalitarianism, and this period effect will be stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 1b).

Secularization

Traditional religious institutions have long prescribed and actively enforced social norms regarding which activities and behaviors are considered appropriate for men and women, assigning women a separate and subordinate position in society confined to the care for children and household chores (Inglehart and Norris 2003; Peek et al. 1991). According to Voas, McAndrew and Storm (2013, p. 264): “[t]he conservative ethos of religious organizations validates and reinforces the choice [of a woman] to be a home-maker.” Over the past decades, the Netherlands has witnessed a dramatic decline in church membership, church attendance, and religious beliefs (De Graaf and Te Grotenhuis 2008). This process of secularization is supposed to have weakened the strength of traditional gender norms, leading people to dissociate themselves from their prescribed roles as homemakers or breadwinners (Inglehart and Norris 2003). Previous studies indeed found higher levels of support for gender egalitarianism among non-religious individuals (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004; Thornton et al. 1983; Voicu 2009). With advancing secularization, people in their emerging adult years are likely socialized into an increasingly egalitarian cultural climate, which may have instilled higher levels of support for gender egalitarianism in these cohorts. We thus expect that the higher the level of secularization in society to which people are exposed during emerging adulthood, the stronger people will support gender egalitarianism, and this cohort effect will be stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 2a).

Exposure to a context with higher shares of non-religious people not only may influence support for gender egalitarianism among those in their emerging adult years, but also may affect all individuals in such context. Comparing differences in gender attitudes between U.S. states, Moore and Vanneman (2003) found that people living in states with higher proportions of religious fundamentalists held less egalitarian gender beliefs. Hence, we expect that the decline of religiosity in society exposes both religious and non-religious people to increasingly egalitarian gender norms. We expect that the higher the level of secularization to which people are exposed at a specific historical moment in time, the stronger people will support gender egalitarianism, and this period effect will be stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 2b).

The Feminization of the Labor Force

The rise of women’s labor force participation is one of the most frequently mentioned explanations for the increase in support for gender egalitarianism (Banaszak and Plutzer 1993; Brooks and Bolzendahl 2004; Cotter et al. 2011; Mason and Lu 1988). In the Netherlands, women’s participation in the labor force has increased considerably over the past decades (Merens and Van den Brakel 2014; Pott-Buter 1993). As a consequence, people are more likely to interact with working women as family, friends, neighbors, and colleagues, which may challenge ideas about a traditional division of paid and unpaid labor as well as women’s dependency on men, in turn legitimizing alternative family and childcare arrangements. It is argued that exposure to working women’s ability to be self-reliant and to perform in the labor market induces higher levels of gender egalitarianism (Meuleman et al. 2016). Moreover, societal norms on women’s capability to work outside the home may be more widespread when female labor force participation is higher. Particularly for people during their emerging adult years, socialization in such a normative climate may have a lasting influence on their support for gender egalitarianism. Dotti Sani and Quaranta (2017), for example, showed that adolescents, especially young women, are more likely to internalize gender egalitarian attitudes in countries where women are more emancipated and visible in the public sphere. Yet, the influence of changes in the societal context within one country over time may differ from variation between countries. We therefore formulate the following hypothesis: The higher the level of female labor force participation in society to which people are exposed during emerging adulthood, the stronger people will support gender egalitarianism, and this cohort effect will be stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 3a).

Increased female labor force participation may also influence people who are not in their emerging adult years, exposing the entire population to a more egalitarian normative climate. In addition, employed women’s gender egalitarianism may spillover to other individuals in society, inducing more support for gender egalitarianism independent from people’s own employment status. In a cross-national study, André et al. (2013) indeed found stronger support for gender egalitarianism in countries with higher female labor force participation, particularly among women. By contrast, Meuleman and colleagues (2016) found no such effect, whereas Banaszak and Plutzer (1993) found regional rates of labor force participation in the United States to be related to lower gender egalitarianism among non-working women. Focusing on changes over time instead of differences between countries or regions, Shu and Meagher (2017) found that contextual changes in women’s labor force participation in the United States indeed partly accounted for the rise in support for gender egalitarianism, as well as for the mid-1990s slowdown. Hence, we expect that: The higher the level of female labor force participation to which people are exposed at a specific historical moment in time, the stronger people will support gender egalitarianism, and this period effect will be stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 3b).

Method

To test our hypotheses we employed repeated cross-sectional data from 14 waves of the Cultural Changes in the Netherlands surveys (CV). These data were collected in face-to-face interviews between 1979 and 2006 by The Netherlands Institute for Social Research, and Statistics Netherlands (2016) to monitor opinions about society and culture among the Dutch population. Each wave consists of a representative national sample of around 2000 individuals aged between 16 and 74 years-old. We combined all 14 waves into one pooled dataset, containing 28,091 respondents. We enriched these data with contextual data to measure period- and cohort-specific societal circumstances.

Support for Gender Egalitarianism

Support for gender egalitarianism was measured with the question: “A woman is more suited to raise little children than a man.” Response categories ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). This question relates to a specific aspect of the private dimension of gender egalitarianism (Wilcox and Jelen 1991) and captures a gender essentialist notion of women and men having innately different interests and skills, which may guide preferences for a gender-typed division of roles (Charles 2011). Although gender egalitarianism consists of various dimensions (Davis and Greenstein 2009), other questions on gender egalitarianism in the data were only available in a more limited number of waves. A higher score on the dependent variable indicates more support for gender egalitarianism. We excluded individuals with a missing value on the dependent variable (n = 756, 2.7%).

Individual-Level Characteristics

The respondents’ gender was measured as (0) male or (1) female. We operationalized educational attainment as the respondents’ highest educational level followed. We harmonized the educational categories across the waves, resulting in seven categories of educational attainment ranging from (1) primary education to (7) university education. To measure church attendance, respondents were asked how often they had attended church or any other house of prayer in the past half year, measured in five categories ranging from once a week or more (0) to never (4). In addition, we included a variable indicating whether or not respondents considered themselves a member of any church or religious community (0 = yes; 1 = no). To measure employment status, we combined information about the respondents’ socio-economic position and working hours, based on the commonly used definition of Statistics Netherlands (Janssen and Dirven 2015; Kraaykamp 2012), which distinguishes between full-time employment (more than 35 h a week, coded 0), part-time employment (12–35 h working per week, coded 1), and not in paid employment (0–12 h a week). We grouped respondents in the latter category into four additional categories based on information about their socio-economic position: unemployed (2), household labor (3), pensioned or disabled (4), student (5) or other (6). We included a variable indicating whether there are children in the household (0 = no; 1 = yes). Because people may become more conservative as they age, we included a continuous measure of age of the respondent as a control variable. We excluded missing values on the individual level characteristics (n = 1021, 3.7%).

Historical and Contemporary Contextual Characteristics

To measure historical and contemporary societal circumstances, we complemented the data with contextual information on the average educational level, the share of non-religious people, and women’s participation in the labor force at the province level. The Netherlands is divided into 12 provinces, with on average about 1.5 million inhabitants per province. Considerable differences among these provinces exist in the levels and rates of educational expansion, secularization, and rising female labor force participation. We propose that circumstances at the province level provide a more direct measurement of socialization or exposure than national-level circumstances. Moreover, contextual characteristics on the national level show far less variation.

We measured educational expansion by calculating per province the average educational level of the cohort that entered the labor market (Te Grotenhuis 1999), derived from the Dutch population census 1960 (Statistics Netherlands 1999) and the Dutch labor force surveys 1992, 1994, 1996, and 2016 (Statistics Netherlands 1987, 2016). Labor force entry was determined by adding the number of years required to finish a certain educational level to a cohort’s birth year (excluding those still in education). We used the Dutch Standard Education Classification (SOI), which ranges from 1 (primary education) to 5 (tertiary education). In 1900 the average educational level of people who entered the labor market amounted to 1.06 (SD = .04; M = 1.04, SD = .03, among women and M = 1.07, SD = .05, among men), which is just above primary education level (see Fig. 1s in the online supplement). By 2006, the Dutch educational level had risen to 3.44 (SD = .18; M = 3.55, SD = .21 among women and M = 3.33, SD = .21 among men), corresponding to (upper) secondary education. In the early 1990s, women’s educational level surpassed that of men.

Secularization was measured as the percentage of individuals not belonging to any religious denomination per province, derived from the Dutch population censuses from 1899, 1909, 1920, 1930, 1947, 1960, and 1971 (Statistics Netherlands 1999), the Cultural Changes in the Netherlands surveys 1970–2006 (The Netherlands Institute for Social Research and Statistics Netherlands 2016), and the Socio-cultural Developments in the Netherlands surveys (SOCON) 1979–2011 (Eisinga et al. 2012). Between 1900 and 2006, the share of non-religious individuals increased from 2.6% (2.5% among women and 2.3% among men) to 63.0% (59.2% among women and 67.4% among men) (see Fig. 2s in the online supplement).

Female labor force participation was measured as the percentage of women above 14 years of age who were active in paid labor in each province, based on the number of women in an occupation (excluding those who are [temporarily] unemployed, in education, who do household labor, who are unable to work or who are institutionalized) derived from the Dutch population censuses from 1899, 1909, 1920, 1930, 1947, 1956, 1960, and 1971 (Statistics Netherlands 1999) and on the number of women employed for at least 12 h a week retrieved from the Dutch labor force surveys 1981–2013 (Statistics Netherlands 2014). These statistics do not allow to differentiate between full-time and part-time employment at the province level. The share of women participating in the labor force more than doubled from 16.7% in 1900 to 35.4% in 2006 (see Fig. 3s in the online supplement). However, female labor force participation only slightly increased in the years before the Second World War, and even dropped below 15% afterwards. From the late 1950s, women’s participation on the labor market increased again, but it was not until the second half of the 1980s that women’s employment really took off.

Societal circumstances during people’s emerging adult years were operationalized by calculating for each respondent a 5-year average of each of these three indicators when the respondent was between 16 and 20 years-old. Although there is no general agreement regarding precisely which are the impressionable years, socialization perspectives agree that the period around people’s 18th birth year is important for the formation of attitudes (Arnett 2000; Jennings and Niemi 1981; Krosnick and Alwin 1989). Hence, we consider the emerging adult years between 16 and 20 to be an important part of people’s impressionable years. Furthermore, data for younger ages were not available in the survey. Unfortunately, no information about the province in which people were living during their impressionable years was available. However, according to Statistics Netherlands, only 17% of all residential mobility in 2015 was between provinces. Considering processes of geographical mobility and urbanization in the Netherlands, this percentage likely was lower in the past.

Contemporary societal circumstances that are specific for a certain time period were operationalized by using the average values on the indicators of educational expansion, secularization, and female labor force participation per province from the year preceding the year of the survey (i.e., lagged by one year). Missing values on the historical and contemporary contextual measures were replaced using linear interpolation. Because one of the Dutch provinces (Flevoland) was established only in 1986, we lacked information on cohort-specific circumstances for people in this province. We excluded respondents living in this province from our analyses (1.2%), resulting in a sample size of 26,004 individuals (12,146 men and 13,858 women). Descriptive statistics for the individual and contextual variables are presented in Table 1.

Analytical Strategy

To test our hypotheses, we estimated OLS regression models for men and women separately, using historical and contemporary contextual characteristics as proxies for cohort and period effects (Menard 1991; Rodgers 1990). For this purpose, we included continuous measurements of the percentage tertiary-educated people, the percentage non-religious people, and the percentage employed women during the respondents’ emerging adulthood (instead of birth year) to capture cohort effects, and continuous measurements of these developments during the survey year (instead of survey year itself) to capture period effects. This method allowed us to estimate the separate influences of three indicators of important societal circumstances and, moreover, to provide a more meaningful interpretation of previously proposed theoretical explanations of the rise of public support for gender egalitarianism over time. All cohort- and period-specific contextual characteristics were mean-centred, and the values of the percentage non-religious people and percentage employed women were divided by 10 to facilitate interpretation of the unstandardized coefficients. All control variables, including age, were entered as dummy variables to allow for possible non-linear relationships with the dependent variable. Because we expect the influence of all contextual characteristics to differ between men and women, we analyzed models for men and women separately. To assess whether the effects for men and women are significantly different, we used a z-test for the difference between two regression coefficients, based on the work of Paternoster et al. (1998).

First, we analyzed the influence of cohort- and period-specific indicators of educational expansion, secularization, and feminization of the labor force separately, while controlling for a dummified age variable (see Table 1s in the online supplement). To analyze the influence of each of these developments net of one another, we subsequently included all contextual characteristics simultaneously in one model. We could, however, not obtain reliable estimates due to harmful multicollinearity resulting from the confounding of the contextual characteristics with age. One solution to this conundrum is to impose a restriction on the effect of age, that is, we constrained the effects for all respondents between 16 and 29 years of age to be equal (following the approach of Firebaugh and Chen 1995). This restriction can be theoretically justified because younger men and women, who generally are not yet confronted with the care for little children, are likely to respond similarly to the question whether women and men are equally suited to raise little children, whereas older people may respond differently depending on their experiences regarding family formation and parenthood. In the Netherlands, the average age at which couples expect their first child lies around 29 years (Statistics Netherlands 2017). Previous studies indeed showed that support for gender egalitarianism decreases after marriage, and after the birth of the first child (Baxter et al. 2015; Corrigall and Konrad 2007).

Moreover, models, in which we separately analyzed the influence of cohort- and period-specific educational expansion, secularization, and feminization of the labor force while controlling for age (see Table 1s in the online supplement), showed that the older people are, the less they support gender egalitarianism, starting from their mid-thirties. People aged 16 to 29 years-old seem not to differ in their support for gender egalitarianism (see Fig. 4s in the online supplement), providing statistical support for a restriction on age. We therefore collapsed the age dummies for respondents aged between 16 and 29 into one reference category, and we included all other age dummies in our models to control for age effects. This allowed us to analyze the influence of our contextual characteristics simultaneously in Models 1a and 1b, while controlling for age. Because the structure of the population may change with respect to individual characteristics that dispose people toward more support for gender egalitarianism, we included the individual characteristics in Model 2a and 2b to account for compositional differences.

Results

Support for Gender Egalitarianism over Time

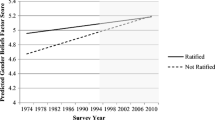

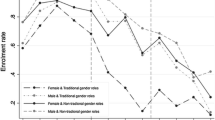

Figure 1 shows the trend in support for gender egalitarianism for men and women in the Netherlands over time. The average level of support for gender egalitarianism among men increased from 2.5 in 1979 to almost 2.8 in 1996 (on a scale from 1 to 5). Women’s support for gender egalitarianism is higher and increased somewhat stronger from 2.8 in 1979 to 3.4 in 1996. Between 1997 and 2002, however, the trend reversed slightly and stabilized after 2002.

Contributions to the Upward Trend in Support for Gender Egalitarianism

Table 2 shows the multivariate results from regression analyses including period- and cohort-specific contextual characteristics simultaneously, controlled for age. Models 1a and 1b demonstrate that socialization in times of a higher average educational level in the population during people’s emerging adult years exerts a substantial positive and significant influence on men’s (b = .42, p < .001) and women’s (b = .92, p < .001) support for gender. For example, women socialized in times of the highest average level of education in Dutch society (3.78) score on average 2.40 points higher (on a scale from 1 to 5) on the measure of gender egalitarianism as compared to women socialized when the average educational level in the Netherlands was at its lowest point (1.17)—calculation: (3.78–1.17) * .92 = 2.40. The standardized coefficients indicate that the influence of cohort-specific educational expansion is twice as strong for women (β = .43) as for men (β = .21). The difference between the regression coefficients for men and women is significant (z = −3.96, p < .001). This provides preliminary support for Hypothesis 1a. Exposure to a higher average educational level in society at a specific historical moment in time (i.e., in times of the survey year) has an additional positive influence on both men’s (b = .26, p = .01; β = .05) and women’s (b = .44, p < .001; β = .08) support for gender egalitarianism, although the standardized coefficients show that these effects are less strong as compared to the influence of educational expansion during emerging adulthood. The effect is not significantly stronger for women than for men (z = −1.26, p = .21). Thus, we find partial support for Hypothesis 1b.

Models 1a and 1b show that socialization in times of higher shares of non-religious people during people’s emerging adult years has a small yet significant influence on men’s support for gender egalitarianism (b = .05, p < .001; β = .09), whereas such effect is absent for women. This suggests that Hypothesis 2a is only partially supported. Exposure to higher shares of non-religious people in society at a specific historical moment in time (i.e., in times of the survey year) exerts a small significant influence on women’s support for gender egalitarianism (b = .07, p < .001; β = .08), but not on men’s. Hence, Hypothesis 2b also seems only partially supported.

Contrary to our expectation, socialization in times of higher female labor force participation during emerging adulthood is related to significantly lower levels of support for gender egalitarianism among men (b = −.12, p < .001; β = −.04) and women (b = −.20, p < .001; β = −.07). This would lead to a rejection of Hypothesis 3a. Yet, Dutch women’s participation on the labor market remained rather stable for a long period, and even declined during the first half of the 1950s. Only since then, people in the Netherlands started to be exposed to rising female labor force participation.

Model 1a and 1b show a negative effect of period-specific female labor force participation for both men (b = −.16, p < .001; β = −.08) and women (b = −.31, p < .001; β = −.14), indicating that exposure to working women in society at a specific historical moment in time (i.e., in times of the survey year) also reduces people’s support for gender egalitarianism. Additional analyses showed that this effect of period-specific labor force participation was positive when analyzed in a model without educational expansion (see Table 1s in the online supplement), but the effect turned negative (but remained significant) once the level of educational expansion was taken into account. This may be due to the high correlation between educational expansion and female labor force participation (the correlation matrix is presented in Table 2s in the online supplement). Hence, this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Table 2 also presents a coefficient which summarizes the effects of all age dummies in the model. This so-called Sheaf-coefficient is to be interpreted as a standardized regression coefficient and is always positive (Heise 1972). To ascertain the direction of the age effect, we plotted the b-coefficients of all age dummies (see Fig. 5s in the online supplement). The results show that the older men are, the less they support gender egalitarianism, whereas there is no significant age effect for women. Model 1 explains 10.7% of the variance among men and 12.5% among women.

In Models 2a and 2b in Table 2, individual characteristics are taken into account to control for compositional differences in the structure of the population. The results show that the influences of historical and contemporary societal circumstances on gender egalitarianism remain present once accounted for people’s structural positions in society. The estimates of educational expansion and secularization become slightly smaller, indicating that a small part of these contextual effects is due to changes in the composition of the population with respect to the individual characteristics. The negative influence of period-specific female labor force participation becomes somewhat stronger for both men and women once the individual characteristics are taken into account. This suggests that shifts in the population composition, for a small part, counterbalance the negative influence of exposure to women on the labor market. The individual-level characteristics in Model 2a and 2b indicate that support for gender egalitarianism is stronger among higher educated people, people who attend church less than once a week, non-religious people, full-time and part-time working men and women, men working in the household, and when there are no children present in the household. The variance explained by our final model amounts to 13.7% for men and 17.5% for women.

To summarize, people who are exposed to a higher average educational level in society, particularly during their emerging adult years, support gender egalitarianism more, independent of their own social position. This pattern supports Hypotheses 1a and 1b, although it is only the socialization effect that is stronger for women than for men. Being socialized in a more secular society increases men’s, but not women’s support for gender egalitarianism, which only partly supports Hypothesis 2a. On the contrary, women who were exposed to higher shares of non-religious people in a specific time period showed more support for gender egalitarianism, over and above their own level of religiosity, but this relationship was not found among men. This pattern confirms Hypothesis 2b, although for women only. Finally, socialization in times of higher female labor force participation did not have the expected positive influence on support for gender egalitarianism, and people who have been exposed to larger shares of employed women in society seem to support gender egalitarianism less once accounting for the level of educational expansion in society. This pattern contradicts Hypothesis 3a and 3b. Of all characteristics in the model, educational expansion during emerging adulthood was found to be the most important indicator of support for gender egalitarianism.

Additional Analyses

Because our dependent variable is an ordinal outcome measure, we performed an additional analysis of the final model using an ordinal logistic regression procedure (polytomous universal models or PLUM in SPSS) as a robustness check. The results are highly similar to the outcomes of our linear regression model (see Table 3s in the online supplement). We also analyzed the contextual influence of gender-specific educational expansion and secularization on men’s and women’s support for gender egalitarianism. For example, we analyzed whether the rise of men’s educational levels in society influenced women’s support for gender egalitarianism (see Table 4s in the online supplement), and vice versa (see Table 5s in the online supplement). These analyses do not alter our conclusions, with the exception that exposure to higher educated women in society in times of the survey year has no significant influence on men’s support for gender egalitarianism. Moreover, we analyzed the final model excluding respondents still in their late adolescence and preadult years (between 16 and 20 years). This analysis yielded highly similar results (see Table 6s in the online supplement).

Lastly, we lacked information about the province in which respondents lived during their impressionable years. Because higher educated respondents are more likely to have moved between provinces during the transition to adulthood (most notably to attend a university), we may have overestimated the cohort effect among higher educated respondents. As a robustness check, we ran our model on a selection of respondents excluding tertiairy educated respondents (those with a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree). The results are highly similar, with the exception that the effects among men became slightly smaller and the (already small and marginally significant) effects of cohort-specific female labor force participation and period-specific educational expansion become non-significant (see Table 7s in the online supplement). This suggests that we may have slightly overestimated the cohort effects among men, although we believe that our overall conclusions remain valid.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to answer the question to what extent changes in the historical and contemporary societal context have contributed to the trend toward stronger support for gender egalitarianism among men and women in the Netherlands. Using data from 16 waves of nationally representative surveys collected in the Netherlands between 1979 and 2006, we showed that the liberalizing trend toward greater gender egalitarianism that has been found in a wide range of countries (e.g., Cotter et al. 2011; Inglehart and Norris 2003; Lee et al. 2007) was also present in the Netherlands.

We empirically analyzed the influence of three important and widely theorized societal developments that have taken place in many countries over the past decades, including the Netherlands: educational expansion, secularization, and the rise of female labor force participation. Whereas previous research mainly focused on temporal indicators of birth cohort and time period to explain the rise in support for gender egalitarianism over time, we used contextual measures of these three developments as indicators of the societal context during the respondents’ emerging adult years and in specific historical times when the survey was held. In this way, we offered a closer look into the black box of why people living and growing up in different times vary in their support for gender egalitarianism.

We showed that changes in the societal context in which people have grown up and live contributed to the upward trend in support for gender egalitarianism. Of the three explanations we tested, educational expansion proved the most important societal development that contributed to the upward trend. The cohort-specific effect of educational expansion was particularly strong, which suggests that people in their emerging adult impressionable years are especially susceptible to the societal climate, providing support for the socialization perspective (Mannheim 1952). That is, due to educational expansion, subsequent cohorts have been socialized in a more egalitarian-normative climate, which has induced support for egalitarianism regarding the care for little children among men, and especially among women. Exposure to such a climate exerts an additional influence on people’s support for gender egalitarianism, independent of their own social position (Alwin and McCammon 2003). Additionally, although the contribution of secularization is modest, increased shares of secular individuals in Dutch society during people’s emerging adult years have promoted some support for gender egalitarianism among men, whereas a higher share of secular individuals in the year preceding the survey positively influenced women’s support for gender egalitarianism. A possible explanation for this differential finding is that men are, in general, less religious than women are and leave the church at younger ages. Moreover, it is argued that religious socialization differs between men and women (Trzebiatowska and Bruce 2012). As a consequence, men may be more impressionable to secular influences in the social context during emerging adulthood than are women.

In contrast to our hypotheses, we found that exposure to the rise of female labor force participation could not in itself explain the upward trend in support for gender egalitarianism, that is, not independently from educational expansion. Given that women’s labor force participation in the Netherlands remained stable at a rather low level during the first half of the twentieth century and only started to rise substantially since the late 1980s, many Dutch cohorts had been exposed to low levels of female labor force participation during emerging adulthood. Kraaykamp (2002) also observed high levels of female labor force participation in people’s pre-adult years to be related to more conservative attitudes toward premarital and extramarital sexuality in the Netherlands. Moreover, we found that people who are exposed to higher rates of female labor force participation during later periods support gender egalitarianism less, after accounting for the level of educational expansion. Hence, the positive influence of female labor force participation may be entirely driven by the expansion of educational levels in society. Given the high correlation between educational expansion and female labor force participation, however, this result should be interpreted with caution.

Alternatively, a theoretical explanation may be proposed. As argued in previous research (see Cotter et al. 2011), the increased participation of women in the labor market has possibly evoked a discussion in society about motherhood and who should care for children when women work (Damaske 2013). This argument may as well apply to the Dutch context. Although support for mothers’ employment is high in the Netherlands (Merens and Van den Brakel 2014) and views toward men’s and women’s (natural) roles concerning the care for little children have become increasingly egalitarian, a strong motherhood ideology—with the mother seen as primarily responsible for the child’s well-being—has long been present in the Netherlands, originating from its strong Christian tradition and emphasized by the government as women’s contribution to the rebuilding of the country after the Second World War (Knijn 1994). With women’s rising education and labor force participation, this motherhood ideology may have become more culturally salient (Douglas and Michaels 2005; Hays 1996). For example, Damaske (2013, p. 441) argued that “the tension between rising workforce participation and intensive mothering, …appears resolved not through a reduction in mothering efforts, but through a discourse that emphasizes conformity to good mothering ideals.” In a context in which women’s employment becomes more common, women (and especially working mothers) may adopt more traditional views on childcare responsibilities as a strategy to legitimize their lower commitment to their careers and/or their higher involvement with childcare and household tasks as compared to men (Johnston and Swanson 2006).

Moreover, increased labor force participation in the Netherlands does not necessarily reflect an increasingly egalitarian societal discourse. About three-quarters of Dutch women in paid labor work part-time, and the majority of women works in traditionally female sectors such as education and care (Merens and Van den Brakel 2014). In addition, full-time working women in the Netherlands generally spend more time on household tasks and childcare than men do (Merens and Van den Brakel 2014). Hence, women’s increased participation in the labor force has not yet been met with symmetrical changes in men’s position in the public and private domain (England 2010). Unfortunately, the available data did not allow a distinction between part-time and full-time employment of women. This may be an important contribution to the present study, especially in the context of the Netherlands. Future research should further explore the role of female labor force participation—and mother’s employment in particular—for explaining trends in public support for gender egalitarianism, taking into account occupational segregation and part-time employment.

Lastly, in line with previous research (Dotti Sani and Quaranta 2017), we found that the influence of changes in the societal context was generally stronger for women than for men. Young women appear the forerunners in the process toward more gender egalitarianism, which signifies their greater interest in promoting gender equality (Bolzendahl and Myers 2004). Notwithstanding, men’s support for gender egalitarianism also has benefited from the rise of societal educational levels and secularism during their emerging adult years.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations and directions for future research should be discussed. First, only one item in the data was suited to indicate changes in support for gender egalitarianism in the Netherlands over a longer period of time. Although gender egalitarianism consists of various dimensions (Davis and Greenstein 2009), we could only study one dimension related to the raising of little children. We thus may have sketched an incomplete picture of changes in gender ideology in the Netherlands. Yet, the trend in this measure of gender egalitarianism is highly comparable to trends in other measures of gender egalitarianism that have been found in various studies (e.g., Cotter et al. 2011; Pepin and Cotter 2018; Shu and Meagher 2017). To what extent the indicators studied here also contributed to trends in other measures of gender egalitarianism remains a question for future research.

Second, we could not explain why support for gender egalitarianism temporarily reversed in the Netherlands in the late 1990s, despite continuing educational expansion, secularization, and rising female labor force participation. Yet, this finding is highly consistent with a reversal of the trend during the same period in other parts of the world (e.g., in the United States: Cotter et al. 2011; Shu and Meagher 2017; Australia: Van Egmond et al. 2010), in particular with regard to attitudes about the role of men and women in the family (Pepin and Cotter 2018). This suggests that a rather universal development that is not limited to a specific national context may explain the stalled gender revolution in the 1990s. For example, Shu and Meagher (2017) found that a rise of men’s overwork partially accounted for the stagnation in Americans’ gender attitudes. Such a rise in men’s overwork may have also taken place in the Netherlands, but it remains to be seen whether this explanation holds in the Dutch context. Another possible explanation is that rising female labor force participation has induced an essentialist counter-reaction in the family domain (Cotter et al. 2011). Whether progress of women’s positions in the public domain indeed produces resistance to egalitarianism in the private domain (Pepin and Cotter 2018) needs further investigation.

Third, absence of information on the province in which respondents lived after 2006 hindered the inclusion of contextual data for more recently interviewed respondents. Moreover, respondents were not asked in which province they had lived during their emerging adult years. As a consequence, we could not exactly determine the geographical context of the respondents’ emerging adulthood because they may have moved in the years between their youth and the moment of the interview. This is a serious limitation, which we are unfortunately unable to resolve. Yet, only 17% of residential mobility takes place between provinces (Statistics Netherlands 2018), and we have shown that our conclusions are fairly robust. We also lacked information on the employment status of the respondents’ mother and partner, which both may affect people’s support for gender egalitarianism. In addition, fathers’ part-time work and involvement in the family during people’s, and especially men’s, emerging adult years may also influence their support for the statement that women and men are equally suited to raise little children. Studies that aim to explain trends in gender egalitarianism may benefit from including other indicators of socialization at different levels, such as the family or the neighborhood.

Lastly, our study is limited to three contextual indicators of historical societal circumstances due to the lack of other contextual measures going back to the early adult years of the older cohorts in the data. Previous studies have argued that, among others, rising employment of married mothers, increased divorce rates, declining fertility, and the emergence of women’s movements may have advanced public support for gender egalitarianism (Brewster and Padavic 2000; Brooks and Bolzendahl 2004; Cotter et al. 2011; Inglehart and Norris 2003; Lee et al. 2007; Pampel 2011; Shorrocks 2016). Family policies may also play a role in changing public views on gender egalitarianism. Unfortunately, it is not possible to directly test the influence of these developments because such data are not available in the Netherlands at the level of provinces. Future research could take more historical and contemporary contextual factors into account, although such data are scarce, if available at all.

Practice Implications

Gender equality, particularly in the field of education, has been high on the policy agenda in the Netherlands. Emancipation policies have been primarily aimed at increasing girls’ participation rates and advancement to higher levels of education, and they have successfully done so over the past decades (Van Hek et al. 2015). By increasing women’s educational levels, these policies have secondarily also propelled support for gender egalitarianism, which in turn may advance girls’ and women’s educational and occupational opportunities even further. This suggests that progress in one domain may spillover to other domains of gender equality.

However, it seems that women have reacted more strongly to changes in the normative climate than men have, given women’s stronger interest in adopting gender egalitarian attitudes and/or because emancipation policies in the Netherlands have been mainly directed at girls and women. Moreover, women’s increased educational and occupational participation has not yet been matched with men’s equal involvement in the household (Merens and Van den Brakel 2014). Nonetheless, our findings showed that men also adopt more gender egalitarian attitudes in response to changes in the societal context. Promoting an emancipatory societal context therefore has the potential to further enhance gender equality.

Conclusion

Our study highlights that the societal normative climate to which people are exposed, especially during their early adult years, plays an important role in shaping their current views on gender egalitarianism. Promoting educational levels within the population seems to have far-reaching benefits for advancing support for gender equality, not only for men and women who obtain higher educational levels themselves, but also for society writ large.

References

Alwin, D. F., & McCammon, R. J. (2003). Generations, cohorts, and social change. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 23–49). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

André, S., Gesthuizen, M., & Scheepers, P. (2013). Support for traditional female roles across 32 countries: Female labour market participation, policy models and gender differences. Comparative Sociology, 12(4), 447–476. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-12341270.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469.

Banaszak, L. A., & Plutzer, E. (1993). Contextual determinants of feminist attitudes. National and subnational influences in Western Europe. American Political Science Review, 87(1), 145–157.

Bar Haim, E., & Shavit, Y. (2013). Expansion and inequality of educational opportunity: A comparative study. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 31, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2012.10.001.

Baxter, J., & Kane, E. W. (1995). Dependence and independence. A cross-national analysis of gender inequality and gender attitudes. Gender and Society, 9(2), 193–215.

Baxter, J., Buchler, S., Perales, F., & Western, M. (2015). A life-changing event: First births and men’s and women’s attitudes to mothering and gender divisions of labour. Social Forces, 93(3), 989–1014. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou103.

Becker, J., & De Hart, J. (2006). Godsdienstige veranderingen in Nederland [Religious changes in the Netherlands]. Retrieved from http://www.scp.nl/Publicaties/Alle_publicaties/Publicaties_2006/Godsdienstige_veranderingen_in_Nederland.

Bolzendahl, C. I., & Myers, D. J. (2004). Feminist attitudes and support for gender equality: Opinion change in women and men, 1974-1998. Social Forces, 83(2), 759–789. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0005.

Brewster, K. L., & Padavic, I. (2000). Change in gender-ideology, 1977-1996: The contributions of intracohort change and population turnover. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00477.x.

Brooks, C., & Bolzendahl, C. (2004). The transformation of US gender role attitudes: Cohort replacement, social-structural change, and ideological learning. Social Science Research, 33(1), 106–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00041-3.

Charles, M. (2011). A world of difference: International trends in women’s economic status. Annual Sociological Review, 37, 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102548.

Ciabattari, T. (2001). Changes in men’s conservative gender ideologies: Cohort and period influences. Gender and Society, 15(4), 574–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015004005.

Corrigall, E. A., & Konrad, A. M. (2007). Gender role attitudes and careers: A longitudinal study. Sex Roles, 56(11–12), 847–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9242-0.

Cotter, D., Hermsen, J. M., & Vanneman, R. (2011). The end of the gender revolution? Gender role attitudes from 1977 to 2008. American Journal of Sociology, 117(1), 259–289. https://doi.org/10.1086/658853.

Damaske, S. (2013). Work, family, and accounts of mothers’ lives using discourse to navigate intensive mothering ideals. Sociology Compass, 7(6), 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12043.

Davis, S. N., & Greenstein, T. N. (2009). Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115920.

De Graaf, N. D., & Te Grotenhuis, M. (2008). Traditional Christian belief and belief in the supernatural: Diverging trends in the Netherlands between 1979 and 2005? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47(4), 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00428.x.

Dotti Sani, G. M., & Quaranta, M. (2017). The best is yet to come? Attitudes toward gender roles among adolescents in 36 countries. Sex Roles, 77(1–2), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0698-7.

Douglas, S., & Michaels, M. (2005). The mommy myth: The idealization of motherhood and how it has undermined all women. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Eisinga, R., Kraaykamp, G., Scheepers, P., & Thijs, P. (2012). Religion in Dutch society 2011–2012. Documentation of a national survey on religious and secular attitudes and behaviour in 2011–2012 (DANS data guide, 11). Amsterdam: Pallas Publications.

England, P. (2010). The gender revolution: Uneven and stalled. Gender and Society, 24(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210361475.

Epstein, C. (2007). Great divides: The cultural, cognitive, and social bases of the global subordination of women. American Sociological Review, 72(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240707200101.

Firebaugh, G. (1992). Where does social change come from? Estimating the relative contributions of individual change and population turnover. Population Research and Policy Review, 11(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00136392.

Firebaugh, G., & Chen, K. (1995). Vote turnout of nineteenth amendment women: The enduring effect of disenfranchisement. American Journal of Sociology, 100(4), 972–996.

Fortin, N. M. (2005). Gender role attitudes and the labour-market outcomes of women across OECD countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21(3), 416–438. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/gri024.

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Heise, D. R. (1972). Employing nominal variables, induced variables, and block variables in path analyses. Sociological Methods and Research, 1(2), 147–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/004912417200100201.

Inglehart, R. F. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies (Vol. 19). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R. F., & Norris, P. (2003). Rising tide. Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Janssen, B., & Dirven, H.-J. (2015). Werkloosheid: Twee afbakeningen. Sociaaleconomische trends 2015/2. [Unemployment: Two delineations. Socioeconomic trends 2015/2]. The Hague: Statistics Netherlands.

Jennings, M. K. (2006). The gender gap in attitudes and beliefs about the place of women in American political life: A longitudinal, cross-generational analysis. Politics and Gender, 2, 193–219. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X06060089.

Jennings, M. K., & Niemi, R. G. (1981). Generations and politics: A panel study of young adults and their parents. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Johnston, D. D., & Swanson, D. H. (2006). Constructing the “good mother”: The experience of mothering ideologies by work status. Sex Roles, 54(7–8), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9021-3.

Knijn, T. (1994). Social dilemmas in images of motherhood in the Netherlands. The European Journal of Women’s Studies, 1, 183–205.

Kraaykamp, G. (2002). Trends and countertrends in sexual permissiveness: Three decades of attitude change in the Netherlands 1965–1995. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 225–239.

Kraaykamp, G. (2012). Employment status and family role attitudes: A trend analysis for the Netherlands. International Sociology, 27(3), 308–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580911423046.

Krosnick, J. A., & Alwin, D. F. (1989). Aging and susceptibility to attitude change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 416–425.

Lee, K. S., Alwin, D. F., & Tufiş, P. A. (2007). Beliefs about women’s labour in the reunified Germany, 1991-2004. European Sociological Review, 23(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm015.

Mannheim, K. (1952). The problem of generations. In P. Kecskemeti (Ed.), Essays in the sociology of knowledge (Vol. 5, pp. 276–322). Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Mason, K. O., & Lu, Y.-H. (1988). Attitudes towards women’s familial roles: Changes in the United States, 1977-1985. Gender and Society, 2(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124388002001004.

Menard, S. (1991). Longitudinal research: Quantitative applications in the social sciences. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Merens, A., & Van den Brakel, M. (2014). Emancipatiemonitor 2014 [Emancipation monitor 2014]. Retrieved from https://www.scp.nl/Publicaties/Alle_publicaties/Publicaties_2014/Emancipatiemonitor_2014.

Meuleman, R., Kraaykamp, G., & Verbakel, E. (2016). Do female colleagues and supervisors influence family role attitudes? A three-level test of exposure explanations among employed men and women in 27 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79, 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12335.

Moore, L. M., & Vanneman, R. (2003). Context matters: Effects of the proportion of fundamentalists on gender attitudes. Social Forces, 82(1), 115–139.

Neve, R. J. M. (1995). Changes in attitudes toward women’s emancipation in the Netherlands over two decades: Unraveling an trend. Social Science Research, 24, 167–187.

Pampel, F. (2011). Cohort changes in the socio-demographic determinants of gender egalitarianism. Social Forces, 89(3), 961–982. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2011.0011.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36(4), 859–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01268.x.

Peek, C. W., Lowe, G. D., & Williams, L. S. (1991). Gender and God’s word: Another look at religious fundamentalism and sexism. Social Forces, 69(4), 1205–1221. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/69.4.1205.

Pepin, J. R., & Cotter, D. A. (2018). Separating spheres? Diverging trends in youth’s gender attitudes about work and family. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12434.

Pott-Buter, H. A. (1993). Facts and fairy tales about female labour, family and fertility: A seven-country comparison, 1850–1990. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Rodgers, W. L. (1990). Interpreting the components of time trends. Sociological Methodology, 20, 421–438. https://doi.org/10.2307/271092.

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Association, 30(6), 843–861.

Scott, J., Alwin, D. F., & Braun, M. (1996). Generational changes in gender-role attitudes: Britain in a cross-national perspective. Sociology, 30(3), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038596030003004.

Sears, D. O. (1983). The persistence of early political predispositions. The roles of attitude object and life stage. In L. Wheeler & P. Shaver (Eds.), Review of personality and social psychology, Vol. 4 (pp. 79–116). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Shorrocks, R. (2016). A feminist generation? Cohort change in gender-role attitudes and the second-wave feminist movement. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(1), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw028.

Shu, X., & Meagher, K. D. (2017). Beyond the stalled gender revolution: Historical and cohort dynamics in gender attitudes from 1977 to 2016. Social Forces, 96(3), 1243–1274. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sox090.

Statistics Netherlands. (1987). Enquête beroepsbevolking (EBB) jaargangen 1987 t/m 2012 [labour force survey (LFS) years 1987 to 2012] [data file]. The Hague: DANS. https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xmh-qg63.

Statistics Netherlands. (1999). Thematic collection: Dutch censuses 1795-1971. The Hague: DANS. https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-x6t-brh5.

Statistics Netherlands. (2014). Beroepsbevolking; provincie naar geslacht 12-uursgrens (1981–2013 [Labour force: province by sex 12-hours threshold (1981–2013)] [Data file]. Retrieved from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/80068ned/table?dl=17AE5.

Statistics Netherlands. (2016). Enquête beroepsbevolking (EBB) 2016 [Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2016] [Data file]. The Hague: DANS. https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-26j-x8wp.

Statistics Netherlands. (2017). Birth; key figures [Data file]. Retrieved from http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=37422ENG&D1=1&D2=a&LA=EN&VW=T.

Statistics Netherlands. (2018). Bevolking en bevolkingsontwikkeling; per maand, kwartaal en jaar [Population and population dynamics by month] [Data file]. Retrieved from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/37943ned/table?ts=1544384927641.

Te Grotenhuis, M. (1999). Ontkerkelijking: Oorzaken en gevolgen (Doctoral dissertation). Radboud University, Nijmegen.

The Netherlands Institute for Social Research & Statistics Netherlands. (2016). Thematische collectie: Culturele Veranderingen in Nederland (CV) en SCP Leefsituatie index (SLI) [thematic collection: Cultural changes in the Netherlands and living situation index] [data file]. The Hague: DANS. https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-zpa-9uwp.

Thijs, P., Te Grotenhuis, M., & Scheepers, P. (2017). The relationship between societal change and rising support for gender egalitarianism among men and women: Results from counterfactual analyses in the Netherlands, 1979–2012. Social Science Research, 68 , 176–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.05.004.

Thornton, A., Alwin, D. F., & Camburn, D. (1983). Causes and consequences of sex-role attitudes and attitude change. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 211–227.

Trzebiatowska, M., & Bruce, S. (2012). Why are women more religious than men? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van der Lippe, T., & Van Dijk, L. (2001). Women’s employment in a comparative perspective. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Van Egmond, M., Baxter, J., Buchler, S., & Western, M. (2010). A stalled revolution? Gender role attitudes in Australia, 1986-2005. Journal of Population Research, 27(3), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-010-9039-9.

Van Hek, M., Kraaykamp, G., & Wolbers, M. H. J. (2015). Family resources and male–female educational attainment. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 40, 29–38.

Voas, D., McAndrew, S., & Storm, I. (2013). Modernization and the gender gap in religiosity: Evidence from cross-national European surveys. Kölner Zeitschift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 65, 259–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-013-0226-5.

Vogt, P. W. (1997). Tolerance and education: Learning to live with diversity and difference. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Voicu, M. (2009). Religion and gender across Europe. Social Compass, 56(2), 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0037768609103350.

Wiesmann, S., Boeije, H., Van Doorne-huiskes, A., & Den Dulk, L. (2008). “Not worth mentioning”: The implicit and explicit nature of decision-making about the division of paid and domestic work. Community, Work and Family, 11(4), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800802361781.

Wilcox, C., & Jelen, T. G. (1991). The effects of employment and religion on women’s feminist attitudes. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 1(3), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr0103.

World Economic Forum. (2015). The global gender gap report 2015 (Vol. 25). https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X04267098.

Acknowledgement

Manfred Te Grotenhuis died before publication of this work was completed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 81.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Thijs, P., Te Grotenhuis, M., Scheepers, P. et al. The Rise in Support for Gender Egalitarianism in the Netherlands, 1979-2006: The Roles of Educational Expansion, Secularization, and Female Labor Force Participation. Sex Roles 81, 594–609 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-1015-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-1015-z