Abstract

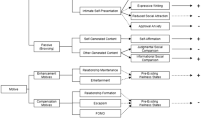

Although previous research demonstrated that networks matter for health-related outcomes, few studies have investigated the possibility that network effects may differ between women and men. In a multivariate regression analysis of a US sample of 548 hurricane victims, we ask whether effects of network composition, density, and size affect perceived adequacy of social support and depressive symptoms more strongly among women than among men. We find evidence for these moderating effects, for direct effects of density on support adequacy and size on depressive symptoms. Our examination of indirect effects of network structure on depressive symptoms, in the pathway through perceived adequacy of social support, suggests that gender may exert more substantial moderating effects than previous health studies suggest.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Antonucci, T. C. (1994). A life-span view of women’s social relations. In B. F. Turner, & L. E. Troll (Eds.), Women growing older: Psychological perspectives (pp. 239–269). Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications.

Antonucci, T. C., & Akiyama, H. (1987). An examination of sex differences in social support among older men and women. Sex Roles, 17, 737–749.

Antonucci, T. C., Akiyama, H., & Lansford, J. E. (1998). Negative effects of close social relations. Family Relations, 47, 379–384.

Bailey, S., & Marsden, P. V. (1999). Interpretation and interview context: Examining the General Social Survey name generator using cognitive methods. Social Networks, 21, 287–309.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2003). The essential difference. The truth about the male and female brain. London: Basic Books.

Beggs, J. J., Haines, V. A., & Hurlbert, J. S. (1996). Situational contingencies surrounding the receipt of informal support. Social Forces, 75, 201–222.

Belle, D. (1982). Lives in stress: Women and depression. Beverly Hills, CA, USA: Sage.

Belle, D. (1987). Gender differences in the social moderators of stress. In R. C. Barnett, L. Biener, & G. K. Baruch (Eds.), Gender and stress (pp. 257–277). New York: The Free Press.

Bem, S. L. (1974). On the utility of alternative procedures for assessing psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 45, 196–205.

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., & Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine, 51, 843–857.

Berkman, L. F., & Syme, S. L. (1979). Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 109, 186–204.

Browne, I., & England, P. (1997). Oppression from within and without in sociological theories: An application to gender. Current Perspectives in Social Theory, 17, 77–104.

Campbell, K. E., Marsden, P. V., & Hurlbert, J. S. (1986). Social resources and socioeconomic status. Social Networks, 8, 97–117.

Chan, Y. K., & Lee, R. P. L. (2006). Network size, social support and happiness in later life: A comparative study of Beijing and Hong Kong. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 87–112.

Chodorow, N. (1978). The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94(Supplement), S95–S120.

Cramer, L. A., Riley, P. J., & Kiger, G. (1991). Support and antagonism in social networks: Effects of community and gender. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6, 991–1005.

Cyranowski, J. M., Frank, E., Young, E., & Shear, M. K. (2000). Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: A theoretical model. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 21–27.

Denton, M., Prus, S., & Walters, V. (2004). Gender differences in health: A Canadian study of the psychosocial, structural and behavioral determinants of health. Social Science and Medicine, 58, 2585–2600.

Dubas, J. S. (2001). How gender moderates the grandparent–grandchild relationship: A comparison of kin-keeper and kin-selector theories. Journal of Family Issues, 22, 478–492.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ellaway, A., & Macintyre, S. (2001). Women in their place: Gender and perceptions of neighbourhoods and health in the West of Scotland. In I. Dyck, N. Davis Lewis, & S. Mcafferty (Eds.), Geographies of women’s health (pp. 265–281). London: Routledge.

Erickson, B. (2003). Social networks: The value of variety. Contexts, 2, 25–31.

Feingold, A. (1994). Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 429–456.

Fischer, C. S. (1982). To dwell among friends: Personal networks in town and city. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Folbre, N. (1993). Micro, macro, choice, and structure. In P. England (Ed.), Theory on gender/feminism on theory (pp. 323–331). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Freedy, J. R., Kilpatrick, D. G., & Resnick, H. S. (1993). Natural disasters and mental health: Theory, assessment, and intervention. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 8, 49–103.

Fuhrer, R., & Stansfeld, S. A. (2002). How gender affects patterns of social relations and their impact on health: A comparison of one or multiple sources of support from ‘close persons’. Social Science and Medicine, 54, 811–825.

Fuhrer, R., Stansfeld, S. A., Chemali, J., & Shipley, M. J. (1999). Gender, social relations and mental health: Prospective findings from an occupational cohort (Whitehall II study). Social Science and Medicine, 48, 77–87.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press.

Glass, T. A., Mendes de Leon, C. F., Seeman, T. E., & Berkman, L. F. (1997). Beyond single indicators of social networks: A LISREL analysis of social ties among the elderly. Social Science and Medicine, 44, 1503–1517.

Granovetter, M. (1982). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. In P. V. Marsden, & N. Lin (Eds.), Social structure and network analysis (pp. 105–130). Beverly Hills, CA, USA: Sage.

Haines, V. A., Beggs, J. J., & Hurlbert, J. S. (2002). Exploring the structural contexts of the support process: Social networks, social statuses, social support, and psychological distress. Advances in Medical Sociology, 8, 269–292.

Haines, V. A., & Hurlbert, J. S. (1992). Network range and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 254–266.

Haines, V. A., Hurlbert, J. S., & Beggs, J. J. (1996). Exploring the determinants of support provision: Provider characteristics, personal networks, community contexts, and support following life events. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37, 252–264.

Haines, V. A., Hurlbert, J. S., & Beggs, J. J. (1999). The disaster framing of the stress process: A test of an expanded model. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 17, 367–397.

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., & Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241, 540–545.

Hurlbert, J. S., Haines, V. A., & Beggs, J. J. (2000). Core networks and tie activation: What kinds of routine networks allocate resources in nonroutine situations? American Sociological Review, 65, 598–618.

Ibarra, H. (1992). Homophily and differential returns: Sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37, 422–447.

Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. H. (1995). In search of altruistic community: Patterns of social support mobilization following hurricane Hugo. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 447–477.

Kavanagh, A. M., Bentley, R., Turrell, G., Broom, D. H., & Subramanian, S. V. (2006). Does gender modify associations between self rated health and the social and economic characteristics of local environments? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 490–495.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 78, 458–467.

Kessler, R. C., & McLeod, J. D. (1984). Sex differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. American Sociological Review, 49, 620–631.

Kessler, R. C., McLeod, J. D., & Wethington, E. (1985). The costs of caring: A perspective on the relationship between sex and psychological distress. In I. G. Sarason, & B.R. Sarason (Eds.), Social support: Theory, research and applications (pp. 491–506). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Nijhoff.

Knipscheer, K. C. P. M., & Antonucci, K. C. (1990). Social network research: Substantive issues and methodological questions. Amsterdam: Swets and Zeitlinger.

Lahelma, E., Martikainen, P., Rahkonen, O., & Silventoinen, K. (1999). Gender differences in ill health in Finland: Patterns, magnitude and change. Social Science and Medicine, 48, 7–19.

Lin, N., Ye, X., & Ensel, W. M. (1999). Social support and depressed mood: A structural analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 344–359.

Marsden, P. V. (1987). Core discussion networks of Americans. American Sociological Review, 52, 122–131.

MacIntyre, S., Hunt, K., & Sweeting, H. (1996). Gender differences in health: Are things really as simple as they seem? Social Science and Medicine, 42, 617–624.

McDonough, P., & Walters, V. (2001). Gender and health: Reassessing patterns and explanations. Social Science and Medicine, 52, 547–559.

McPherson, J. M., & Smith-Lovin, L. (1987). Homophily in voluntary organizations: Status distance and the composition of face-to-face groups. American Sociological Review, 52, 370–379.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Brashears, M. E. (2006). Social isolation in America: Changes in core discussion networks over two decades. American Sociological Review, 71, 353–375.

Miller, J. B. (1987). Toward a new psychology of women. London: Beacon Press.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1990). Control or defense? Depression and the sense of control over good and bad outcomes. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 31, 71–86.

Moore, G. (1990). Structural determinants of men’s and women’s personal networks. American Sociological Review, 55, 726–735.

Moore, S., Shiell, A., Hawe, P., & Haines, V. A. (2005). The privileging of communitarian ideas: Citation practices and the translation of social capital into public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 1330–1337.

Peek, M. K., & Lin, N. (1999). Age differences in the effects of network composition on psychological distress. Social Science and Medicine, 49, 621–636.

Pescosolido, B. A., & Georgianna, S. (1989). Durkheim, suicide, and religion: Toward a network theory of suicide. American Sociological Review, 54, 33–48.

Pett, M. A., Lang, N., & Gander, A. (1992). Late-life divorce: Its impact on family rituals. Journal of Family Issues, 13, 526–552.

Prus, S. G., & Gee, E. (2003). Gender differences in the influence of economic, lifestyle, and psychosocial factors on late-life health. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 94, 306–309.

Pugliesi, K., & Shook, S. L. (1998). Gender, ethnicity, and network characteristics: Variation in social support resources. Sex Roles, 38, 215–238.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3, 249–265.

Reevy, G. M., & Maslach, C. (2001). Use of social support: Gender and personality differences. Sex Roles, 44, 437–459.

Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (1989). Explaining the social patterns of depression: Control and problem-solving—or support and talking? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 206–219.

Ryan, R. M., La Guardia, J. G., Solky-Butzel, J., Chirkov, V., & Kim, Y. (2005). On the interpersonal regulation of emotions: Emotional reliance across gender, relationships, and culture. Personal Relationships, 12, 145–163.

Sachs-Ericsson, N., & Ciarlo, J. A. (2000). Gender, social roles, and mental health: An epidemiological perspective. Sex Roles, 43, 605–628.

Salari, S., & Zhang, W. (2006). Kin keepers and good providers: Influence of gender socialization on well-being among USA birth cohorts. Aging and Mental Health, 10, 485–496.

Seeman, T. E., & Berkman, L. F. (1988). Structural characteristics of social networks and their relationship with social support in the elderly: Who provides support? Social Science and Medicine, 26, 737–749.

Shields, S. A. (1995). The role of emotional beliefs and values during gender development. Review of Personality and Social Psychology, 15, 212–232.

Shye, D., Mullooly, J. P., Freeborn, D. K., & Pope, C. R. (1995). Gender differences in the relationship between social network support and mortality: A longitudinal study of an elderly cohort. Social Science and Medicine, 41, 935–947.

Skrabski, A., Kapp, M., & Kawachi, I. (2003). Social capital in a changing society: Cross-sectional associations with middle aged female and male mortality rates. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 114–119.

Smith-Lovin, L., & McPherson, J. M. (1993). You are who you know: A network approach to gender. In P. England (Ed.), Theory on gender/feminism on theory (pp. 223–251). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Stafford, M., Bartley, M., Mitchell, R., & Marmot, M. (2001). Characteristics of individuals and characteristics of areas: Investigating their influence on health in the Whitehall II study. Health and Place, 7, 117–129.

Stafford, M., Cummins, S., Macintyre, S., Ellaway, A., & Marmot, M. (2005). Gender differences in the associations between health and neighbourhood environment. Social Science and Medicine, 60, 1681–1692.

Stansfeld, S., & Marmot, M. (1992). Deriving a survey measure of social support: The reliability and validity of the close persons questionnaire. Social Science and Medicine, 35, 1027–1035.

Steiner-Pappalardo, N. L., & Gurung, R. A. R. (2002). The femininity effect: Relationship qualitiy, sex, gender, attachment, and significant-other concepts. Personal Relationships, 9, 313–325.

Suitor, J. J., & Pillemer, K. (2002). Gender, social support, and experiential similarity during chronic stress: The case of family caregivers. Advances in Medical Sociology, 8, 247–266.

Szreter, S., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 650–667.

Taylor, J., & Turner, R. J. (2001). A longitudinal study of the role and significance of mattering to others for depressive symptoms. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, 310–325.

Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Extra Issue, 53–79.

Turner, H. A. (1994). Gender and social support: Taking the bad with the good. Sex Roles, 30, 521–541.

Turner, R. J., & Avison, W. R. (1989). Gender and depression: Assessing exposure and vulnerability to life events in a chronically strained population. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 177, 443–455.

Turner, R. J., & Avison, W. R. (2003). Status variations in stress exposure: Implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 488–505.

Turner, R. J., & Marino, F. (1994). Social support and social structure: A descriptive epidemiology. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 193–212.

Turner, H. A., & Turner, R. J. (1999). Gender, social status, and emotional reliance. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 360–373.

Umberson, D., Chen, M. D., House, J. S., Hopkins, K., & Slaten, E. (1996). The effect of social relationships on psychological well-being: Are men and women really so different? American Sociological Review, 61, 837–857.

Vaux, A. (1990). An ecological approach to understanding and facilitating social support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 507–518.

Walker, M. E., Wasserman, S., & Wellman, B. (1993). Statistical models for social support networks. Sociological Methods and Research, 22, 71–98.

Wamala, S. P., & Agren, G. (2004). Gender differences in health. In Encyclopedia of Health and Behavior Management Sage. Retrieved March 19, 2008, from http://www.credoreference.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/entry/5063409.

Wellman, B. (1992). Which types of ties and networks provide what kinds of social support? Advances in Group Processes, 9, 207–235.

Wellman, B., & Frank, K. A. (2001). Network capital in a multilevel world: Getting support from personal communities. In N. Lin, K. Cook, & R. S. Burt (Eds.), Social capital: Theory and research (pp. 233–273). New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Wellman, B., & Wortley, S. (1989). Brothers’ keepers: Situating kinship relations in broader networks of social support. Sociological Perspectives, 32, 273–306.

Wellman, B., & Wortley, S. (1990). Different strokes from different folks: Community ties and social support. American Journal of Sociology, 96, 558–588.

Williams, C. L. (1993). Psychoanalytic theory and the sociology of gender. In P. England (Ed.), Theory on gender/feminism on theory (pp. 131–149). New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was supported by Grant #SES922444 from the National Science Foundation. The first author was supported by the Population Health Intervention Research Centre of the University of Calgary. We thank Bernice Pescosolido for comments on an earlier version of this paper; we also thank the reviewers and editor for their comments.

Appendix

Appendix

Unstandardized coefficients for perceived adequacy of social support and depressive symptoms, interaction terms for female difference.

Independent variable | Perceived adequacy of social support | Depressive symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Main | Female interaction | Main | Female interaction | |

Individual characteristics | ||||

Female | −1.311** | 15.350 | ||

Education | .010 | .016 | −.063 | |

Family income | .001 | −.004 | −.062* | |

Age | −.001 | .496*** | −1.382** | |

Age squared | −.005* | .011** | ||

Race (white) | .006 | .225* | .278 | |

Never married | −.241* | .298* | 4.304 | −7.456* |

Separated/divorced | −.240** | −2.226 | 6.760* | |

Disaster loss | −.036 | −.071 | .473 | 1.798 |

Household dependents | −.048* | 1.160 | −2.986** | |

Chronic health problems | −.153*** | .125 | 4.729** | |

Hurricane experience | −.115 | .161 | −6.508* | 7.441* |

Household insurance | −.045 | −1.656 | −6.040* | |

Social support | ||||

Perceived adequacy | −9.073** | 5.416* | ||

Network structure | ||||

Proportion kin | .020 | .556 | ||

Proportion female | −.108 | .131 | −5.470** | |

Mean closeness | .170 | .578*** | 3.086 | |

Relationship duration | −.038 | .421* | 3.777 | −4.687 |

Size | .046** | −.001 | .960*** | |

Intercept | 3.842 | 34.690 | ||

R 2 | .210 | .297 | ||

N | 548 | 548 | ||

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haines, V.A., Beggs, J.J. & Hurlbert, J.S. Contextualizing Health Outcomes: Do Effects of Network Structure Differ for Women and Men?. Sex Roles 59, 164–175 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9441-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9441-3