Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the influence of recall periods on the assessment of physical function, we compared, in cancer and general population samples, the standard administration of PROMIS Physical Function items without a recall period to administrations with 24-hour and 7-day recall periods.

Methods

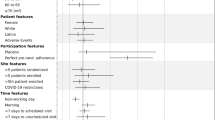

We administered 31 items from the PROMIS Physical Function v2.0 item bank to 2400 respondents (n = 1001 with cancer; n = 1399 from the general population). Respondents were randomly assigned to one of three recall conditions (no recall, 24-hours, or 7-days) and one of two “reminder” conditions (with recall periods presented only at the start of the survey or with every item). We assessed items for potential differential item functioning (DIF) by recall time period. We then tested recall and reminder effects with analysis of variance controlling for demographics, English fluency, and co-morbidities.

Results

Based on conservative pre-set criteria, no items were flagged for recall time period-related DIF. Using analysis of variance, each condition was compared to the standard PROMIS administration for Physical Function (no recall period). There was no evidence of significant differences among groups in the cancer sample. In the general population sample, only the 24-hour recall condition with reminders was significantly different from the “no recall” PROMIS standard. At the item level, for both samples, the number of items with non-trivial effect size differences across conditions was minimal.

Conclusions

Compared to no recall, the use of a recall period has little to no effect upon PROMIS physical function responses or scores. We recommend that PROMIS Physical Function be administered with the standard PROMIS “no recall” period.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Weeks, W. B., & Weinstein, J. N. (2016). Patient-reported data can help people make better health care choices. New England Journal of Medicine. Retrieved from https://catalyst.nejm.org/patient-reported-data-can-help-people-make-better-health-care-choices/. Accessed 18 Dec 2017.

Butt, Z., & Reeve, B. (2012). Enhancing the patient’s voice: Standards in the design and selection of patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) for use in patient-centered outcomes research. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Food and Drug Administration. (2009). Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Federal Register,74(235), 65132–65133.

Brundage, M., Blazeby, J., Revicki, D., Bass, B., de Vet, H., Duffy, H., et al. (2013). Patient-reported outcomes in randomized clinical trials: Development of ISOQOL reporting standards. Quality of Life Research,22(6), 1161–1175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0252-1.

Cella, D., Yount, S., Rothrock, N., Gershon, R., Cook, K., Reeve, B., et al. (2007). The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care,45(Suppl 1), S3–S11. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55.

Cella, D., Riley, W., Stone, A., Rothrock, N., Reeve, B., Yount, S., et al. (2010). Initial adult health item banks and first wave testing of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) network: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,63(11), 1179–1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011.

Calvert, M., Kyte, D., Mercieca-Bebber, R., Slade, A., Chan, A.-W., King, M. T., et al. (2018). Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols. JAMA,319(5), 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.21903.

Cook, K., Jensen, S. E., Schalet, B. D., Beaumont, J. L., Amtmann, D., Czajkowski, S., et al. (2016). PROMIS measures of pain, fatigue, negative affect, physical function, and social function demonstrated clinical validity across a range of chronic conditions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,73, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.038.

Jensen, R. E., Potosky, A. L., Reeve, B. B., Hahn, E., Cella, D., Fries, J., et al. (2015). Validation of the PROMIS physical function measures in a diverse US population-based cohort of cancer patients. Quality of Life Research,24(10), 2333–2344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-0992-9.

Lai, J.-S., Cella, D., Choi, S., Junghaenel, D. U., Christodoulou, C., Gershon, R., et al. (2011). How item banks and their application can influence measurement practice in rehabilitation medicine: A PROMIS fatigue item bank example. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation,92(10), S20–S27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.033.

Broderick, J. E., Schneider, S., Junghaenel, D. U., Schwartz, J. E., & Stone, A. A. (2013). Validity and reliability of patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) instruments in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care & Research,65(10), 1625–1633. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22025.

Rothrock, N., Hays, R., Spritzer, K., Yount, S., Riley, W., & Cella, D. (2010). Relative to the general US population, chronic diseases are associated with poorer health-related quality of life as measured by the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,63(11), 1195–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.012.

Reeve, B., Hays, R., Bjorner, J., Cook, K. F., Crane, P. K., Teresi, J. A., et al. (2007). Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: Plans for the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). Medical Care,45(5), S22–S31. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04.

Schalet, B. D., Revicki, D. A., Cook, K. F., Krishnan, E., Fries, J. F., & Cella, D. (2015). Establishing a common metric for physical function: Linking the HAQ-DI and SF-36 PF subscale to PROMIS physical function. Journal of General Internal Medicine,30(10), 1517–1523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3360-0.

Riley, W., Rothrock, N., Bruce, B., Christodolou, C., Cook, K., Hahn, E., et al. (2010). Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: Further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Quality of Life Research,19(9), 1311–1321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9694-5.

Hays, R. D., Spritzer, K. L., Schalet, B. D., & Cella, D. (2018). PROMIS-29 v2.0 profile physical and mental health summary scores. Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1842-3.

Cella, D., Lai, J.-S., Jensen, S. E., Christodoulou, C., Junghaenel, D. U., Reeve, B. B., et al. (2016). PROMIS® fatigue item bank has clinical validity across diverse chronic conditions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.037.

Liu, H., Cella, D., Gershon, R., Shen, J., Morales, L. S., Riley, W., et al. (2010). Representativeness of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system internet panel. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,63(11), 1169–1178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.021.

Schalet, B. D., Cook, K. F., Choi, S. W., & Cella, D. (2014). Establishing a common metric for self-reported anxiety: Linking the MASQ, PANAS, and GAD-7 to PROMIS anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders,28, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.11.006.

DeWalt, D., Rothrock, N., Yount, S., & Stone, A. A. (2007). Evaluation of item candidates: The PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical Care,45(5 Suppl 1), S12–S21. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2.

Garcia, S. F., Cella, D., Clauser, S. B., Flynn, K. E., Lad, T., Lai, J. S., et al. (2007). Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: A patient-reported outcomes measurement information system initiative,25(32), 5106–5112. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2341.

Schwarz, N., & Sudman, S. (2012). Autobiographical memory and the validity of retrospective reports. New York: Springer.

Bradburn, N. M., Rips, L. J., & Shevell, S. K. (1987). Answering autobiographical questions: The impact of memory and inference on surveys. Science,236(4798), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3563494.

Erskine, A., Morley, S., & Pain, S. P. (1990). Memory for pain: A review. Pain,41, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(90)90002-U.

Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Belief and feeling: Evidence for an accessibility model of emotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin,128(6), 934–960. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.934.

Gorin, A. A., & Stone, A. A. (2001). Recall biases and cognitive errors in retrospective self-reports: A call for momentary assessments. Handbook of Health Psychology,23, 405–413.

Redelmeier, D. A., & Pain, D. K. (1996). Patients’ memories of painful medical treatments: Real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures. Pain,66, 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(96)02994-6.

Menon, G., & Yorkston, E. A. (1999). The use of memory and contextual cues in the formation of behavioral frequency judgments. In A. A. Stone, J. S. Turkkan, C. A. Bachrach, J. B. Jobe, H. S. Kurtzman, & V. S. Cain (Eds.), The science of self-report implications for research and practice (pp. 63–79). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Rose, M., Bjorner, J. B., Becker, J., Fries, J. F., & Ware, J. E. (2008). Evaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,61(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.025.

Rose, M., Bjorner, J. B., Gandek, B., Bruce, B., Fries, J. F., & Ware, J. E., Jr. (2014). The PROMIS physical function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,67(5), 516–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.024.

de Vries, S. T., Haaijer-Ruskamp, F. M., de Zeeuw, D., & Denig, P. (2014). The validity of a patient-reported adverse drug event questionnaire using different recall periods. Quality of Life Research,23(9), 2439–2445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0715-7.

Broderick, J. E., Schwartz, J. E., Vikingstad, G., Pribbernow, M., Grossman, S., & Stone, A. A. (2008). The accuracy of pain and fatigue items across different reporting periods. Pain,139(1), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.024.

Broderick, J. E., Schneider, S., Schwartz, J. E., & Stone, A. A. (2010). Interference with activities due to pain and fatigue: Accuracy of ratings across different reporting periods. Quality of Life Research,19(8), 1163–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9681-x.

Stull, D. E., Leidy, N. K., Parasuraman, B., & Chassany, O. (2009). Optimal recall periods for patient-reported outcomes: Challenges and potential solutions. Current Medical Research and Opinion,25(4), 929–942. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990902774765.

Norquist, J. M., Girman, C., Fehnel, S., DeMuro-Mercon, C., & Santanello, N. (2012). Choice of recall period for patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures: Criteria for consideration. Quality of Life Research,21(6), 1013–1020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-0003-8.

Lai, J.-S., Cook, K., Stone, A., Beaumont, J., & Cella, D. (2009). Classical test theory and item response theory/Rasch model to assess differences between patient-reported fatigue using 7-day and 4-week recall periods. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,62(9), 991–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.007.

Batterham, P. J., Sunderland, M., Carragher, N., & Calear, A. L. (2017). Psychometric properties of 7- and 30-day versions of the PROMIS emotional distress item banks in an Australian adult sample. Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116685809.

Barta, W. D., Tennen, H., & Litt, M. D. (2012). Measurement reactivity in diary research. In M. R. Mehl & M. Connor (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 108–123). New York: Guilford Press.

Yost, K. J., Eton, D. T., Garcia, S. F., & Cella, D. (2011). Minimally important differences were estimated for six patient-reported outcomes measurement information system-cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology,64(5), 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.018.

Northwestern University. (2018). HealthMeasures: Transforming how health is measured. Retrieved from http://www.healthmeasures.net/. Accessed 11 Jan 2018.

Hays, R., Bjorner, J., Revicki, D., Spritzer, K., & Cella, D. (2009). Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. European Journal of Cancer,18(7), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9.

Yanez, B., Pearman, T., Lis, C. G., Beaumont, J. L., & Cella, D. (2012). The FACT-G7: A rapid version of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G) for monitoring symptoms and concerns in oncology practice and research. Annals of Oncology,24(4), 1073–1078. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mds539.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin,107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238.

Cook, K. F., Kallen, M. A., & Amtmann, D. (2009). Having a fit: Impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT’s unidimensionality assumption. Quality of Life Research,18(4), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9464-4.

Hatcher, L. (1994). A step-by-step approach to using SAS for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary: SAS Institute Inc.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling a Multidisciplinary Journal,6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Reise, S. P., Morizot, J., & Hays, R. D. (2007). The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Quality of Life Research,16(Suppl 1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9183-7.

Reise, S. P., Moore, T. M., & Haviland, M. G. (2010). Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment,92(6), 544–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.496477.

Reise, S. P., Bonifay, W. E., & Haviland, M. G. (2013). Scoring and modeling psychological measures in the presence of multidimensionality. Journal of Personality Assessment,95(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.725437.

Rodriguez, A., Reise, S. P., & Haviland, M. G. (2016). Evaluating bifactor models: Calculating and interpreting statistical indices. Psychological Methods,21(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000045.

Choi, S. W., Gibbons, L. E., & Crane, P. K. (2011). Lordif: An R package for detecting differential item functioning using iterative hybrid ordinal logistic regression/item response theory and monte carlo simulations. Journal of Statistical Software,39(8), 1–30.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Released 2017.

Rosenthal, R., Rosnow, R. L., & Rubin, D. B. (2000). Contrasts and effect sizes in behavioral research: A correlational approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Funding

The funding was provided by National Institutes of Health (Grant No. U2CCA186878), AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Condon, D.M., Chapman, R., Shaunfield, S. et al. Does recall period matter? Comparing PROMIS® physical function with no recall, 24-hr recall, and 7-day recall. Qual Life Res 29, 745–753 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02344-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02344-0