Abstract

Purpose

The Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) is a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded initiative to develop reliable, valid, and normed item banks to measure health. We describe the first large-scale translation and cross-cultural adaptation effort to German and Spanish of eight pediatric PROMIS item banks: Physical activity (PAC), subjective well-being (SWB), experiences of stress (EOS), and family relations (FAM).

Methods

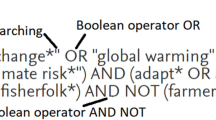

We utilized methods outlined in the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) PRO Translation Task Force recommendations. Ten professional translators performed a translatability assessment and generated forward translations. Forward Translations were compared within a country and cross-culturally to identify problems and to produce a consensus-derived version, which was then back translated, evaluated, and revised where necessary. Reconciled versions were evaluated in cognitive interviews with 126 children before finalization.

Results

Eight resulting pediatric PROMIS® item banks were translated: Two PAC banks (22 total items), three SWB banks (125 total items), two EOS banks (45 total items), and one FAM bank (47 total items). Up to 92% of all items raised no or only minor translation difficulties, 0–5.6% were difficult to translate. Up to 20% item revisions were necessary to ensure conceptual equivalence and comprehensibility. Cognitive interviews indicated that 91–94% of the final items were appropriate for children (8–17 years).

Conclusions

German and Spanish translations of eight PROMIS Pediatric item banks were created for clinical trials and routine pediatric health care. Initial translatability assessment and rigorous translation methodology helped to ensure conceptual equivalence and comprehensibility. Next steps include cross-cultural validation and adaptation studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

25 August 2018

In the original publication of the article, two of the author names “L. A. Schröder, F. Metzner” and email address of the authors “J. Devine, J. Moon, A. C. Haller” were missed out. The correct author group with affiliations are provided in this correction.

Notes

In the following, we will use the term “child” or “children” whenever referring to children and/or adolescents.

An example for an item revision in the 7th step is that the German translation of the PA item “I felt pleased” (FT) was “war ich gut gelaunt,” which translated back to “I was in a good mood” (BT). The reviewer noticed the different concepts between FT and BT and talked to the translators, who then suggested the item revision to “war ich glücklich und zufrieden.” (This was then tested fine within the following CIs with children, i.e., the original concept was covered.)

Abbreviations

- BT:

-

Backward translation

- CAT:

-

Computerized Adaptive Test

- CI:

-

Cognitive interview

- DIF:

-

Differential item functioning

- EMEA:

-

European agency for the evaluation of medicinal products

- EORTC:

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- EuroQol:

-

European Quality of Life Group

- EOS:

-

Experience of stress

- EOS-P:

-

Experience of stress—subdomain: psychological stress responses

- EOS-S:

-

Experience of Stress—subdomain: somatic (physical) stress responses

- FAM:

-

Family relations

- FAM-FB:

-

Family relations—subdomain: family belonging

- FAM-FI:

-

Family relations—subdomain: family involvement

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Agency

- FT:

-

Forward translation

- ISPOR:

-

The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes

- IQOLA:

-

The International Quality of Life Assessment Project

- MOS:

-

Medical outcome trust

- PAC:

-

Physical Activity

- PAC-M:

-

Physical Activity—subdomain mobility

- PAC-S:

-

Physical Activity—subdomain strength

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcome

- PROMIS:

-

Patient-reported outcome measurement information system

- RFT:

-

Reconciled forward translation

- SWB:

-

Subjective well-being

- SWB-PA:

-

Subjective well-being—subdomain positive affect

- SWB-LS:

-

Subjective well-being—subdomain life satisfaction

- SWB-MP:

-

Subjective well-being—subdomain meaning and purpose

- WHOQOL:

-

World Health Organization Quality of Life

References

Cella, D., Yount, S., Rothrock, N., Gershon, R., Cook, K., Reeve, B., et al. (2007). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care, 45(5 Suppl 1), S3–S11. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55.

Cella, D., Riley, W., Stone, A., Rothrock, N., Reeve, B., Yount, S., et al. (2010). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005e2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63, 1179–1194.

Fries, J. F., Krishnan, E., Rose, M., Lingala, B., & Bruce, B. (2011). Improved responsiveness and reduced sample size requirements of PROMIS physical function scales with item response theory. Arthritis Research Therapy, 13(5), R147.

Rose, M., Bjorner, J. B., Gandek, B., Bruce, B., Fries, J. F., & Ware, J. E. Jr. (2014). The PROMIS Physical Function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(5), 516–526.

Khanna, D., Krishnan, E., Dewitt, E. M., Khanna, P. P., Spiegel, B., & Hays, R. D. (2011). The future of measuring patient-reported outcomes in rheumatology: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Arthritis Care Research, 63(Suppl 11), S486–S490.

Riley, W. T., PIlkonis, P., & Cella, D. (2011). Application of the National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to mental health research. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 14(4), 201–208.

Cella, D., Gershon, R., Lai, J. S., & Choi, S. (2007). The future of outcomes measurement: Item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Quality Life Research, 16(Suppl.1), 133–141.

Irwin, D. E., Stucky, B., Langer, M. M., Thissen, D., Dewitt, E. M., Lai, J. S., et al. (2010). An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Quality of Life Research, 19(4), 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9619-3.

Varni, J. W., Stucky, B. D., Thissen, D., DeWitt, E. M., Irwin, D. E., Lai, J.-S., et al. (2010). PROMIS Pediatric Pain Interference Scale: An item response theory analysis of the pediatric pain item bank. The Journal of Pain, 11(11), 1109–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.005.

Bevans, K. B., Gardner, W., Pajer, K., Riley, A. W., & Forrest, C. B. (2013). Qualitative development of the PROMIS® pediatric stress response item banks. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss107.

Forrest, C. B., Bevans, K. B., Tucker, C., Riley, A. W., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Gardner, W., et al. (2012). Commentary: The Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS(R)) for children and youth: Application to pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37(6), 614–621. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jss038.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Devine, J., Bevans, K., Riley, A. W., Moon, J., Salsman, J. M., et al. (2014). Subjective well-being measures for children were developed within the PROMIS project: Presentation of first results. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.018.

Forrest, C. B., Devine, J., Bevans, K. B., Becker, B. D., Carle, A. C., Teneralli, R. E., Moon, J., Tucker, C. A., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2018). Development and psychometric evaluation of the PROMIS Pediatric Life Satisfaction item banks, child-report, and parent-proxy editions. Quality of Life Research, 27(1), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1681-7.

Forrest, C. B., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Devine, J., Becker, B. D., Teneralli, R. E., Moon, J., et al. (2017). Development and evaluation of the PROMIS® pediatric positive affect item bank, child-report and parent-proxy editions. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9843-9.

Dewalt, D. A., Thissen, D., Stucky, B. D., Langer, M. M., Dewitt, M., Irwin, E.D.E., et al (2013). PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships Scale: Development of a peer relationships item bank as part of social health measurement. Health Psychology, 32(10), 1093–1103. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032670.

Bevans, K. B., Riley, A. W., Landgraf, J. M., Carle, A. C., Tenerallis, R. E., Fiese, B. H., Meltzer, L. J., Ettinger, A. K., Becker, B. D., & Forrest, C. B. (2017). Children’s family experiences: Development of the PROMIS pediatric family relationships measures. Quality of Life Research, 26(11), 3011–3023.

Herdman, M., Fox-Rushby, J., & Badia, X. (1997). Equivalence and the translation and adaptation of health-related Quality of Life questionnaires. Quality of Life Research, 6(3), 237–247.

Wild, D., Grove, A., Martin, M., Eremenco, S., McElroy, S., Verjee-Lorenz, A., et al. (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value in Health, 8(2), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x.

Wild, D., Eremenco, S., Mear, I., Martin, M., Houchin, C., Gawlicki, M., et al. (2009). Multinational trials—recommendations on the translations required, approaches to using the same language in different countries, and the approaches to support pooling the data: The ISPOR patient-reported outcomes translation and linguistic validation good research practices Task Force Report. Value in Health, 12(4), 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00471.x.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2009). Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Federal Register 74(235), 65132–65133

European Medicines Agency (2005). Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related Quality of Life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products. London: EMA.

Epstein, J., Santo, R. M., & Guillemin, F. (2015). A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68(4), 435–441.

Acquadro, C., Conway, K., Hareendran, A., Aaronson, N., & Regulatory, E., Issues and Quality of Life Assessment (ERIQA) Group (2008). Literature review of methods to translate health-related Quality of Life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value in Health, 11(3), 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00292.x.

Lenderking, W. R. (2005). Comments on the ISPOR Task Force Report on translation and adaptation of outcomes measures: Guidelines and the need for more research. Value in Health, 8(2), 92–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.08201.x.

WHOQOL Group (1993). Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Quality of Life Research, 2(2), 153–159, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00435734.

The EuroQol Group (2000). Draft guidelines for cultural adaptations of EQ-5D. Rotterdam: EuroQol.

Cull, A., Sprangers, M., Bjordal, K., Aaronson, N., West, K., & Bottomley, A. (2002). EORTC Quality of Life Group Translation Procedure (2nd Edn). Brussels: EORTC.

Guillemin, F., Bombardier, C., & Beaton, D. (1993). Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related Quality of Life measures: Literature review and proposed guidelines. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 46(12), 1417–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N.

MapiGroup (2016). Linguistic Validation. Retrieved March 9, 2017 from https://mapigroup.com/services/language-services/linguistic-validation/.

Medical Outcomes Trust (1997). Trust introduces new translation criteria. Bulletin, 5(4), 3–4.

Eremenco, S., Cella, D., & Arnold, B. J. (2005). A Comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 28(2), 212–232.

IQOLA (2011). The International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Retrieved March 9, 2017 from http://www.iqola.org/project.aspx.

Correia, H. (2010). PROMIS translation methodology: The minimum standard. Evanston: Northwestern University.

Herdman, M., Fox-Rushby, J., & Badia, X. (1997). Equivalence and the translation and adaptation of health-related Quality of Life questionnaires. Quality of Life Research. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026410721664.

Catherine Acquadro, Donald L. Patrick, Sonya Eremenco, Mona L. Martin, Dagmara Kuliś, Helena Correia, Katrin Conway, (2017) Emerging good practices for Translatability Assessment (TA) of Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) measures. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes 2(1).

Mariana, V., Cox, T., Melby, A. (2015). The multidimensional quality metrics (MQM) framework: A new framework for translation quality assessment. The Journal of Specialized Translation. https://www.jostrans.org/issue23/art_melby.pdf.

Drennan, J. (2003). Cognitive interviewing: Verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02579.x.

Irwin, D. E., Varni, J. W., Yeatts, K., & DeWalt, D. A. (2009). Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: A patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-3.

Prüfer, P., & Rexroth, M. (2005). Kognitive Interviews. GESIS-How-to (Vol. 15). Mannheim: Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen.

Prüfer, P., & Rexroth, M. (2000). Zwei-Phasen-Pretesting. In M. u. A. Zentrum für Umfragen (Ed.). ZUMA-Arbeitsbericht (Vol. 2000/08). Mannheim: Zentrum für Umfragen, Mehtoden und Analysen.

Willis, G. B. (2004). Cognitive interviewing. A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

DeWalt, D. A., Rothrock, N., Yount, S., & Stone, A. A. (2007). Evaluation of item candidates: The PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical Care, 45(5), S12–S21. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2.

Liu, Y., Hinds, P. S., Wang, J., Correia, H., Du, S., Ding, J., Gao, W. J., & Yuan, C. (2013). Translation and linguistic validation of the pediatric patient-reported outcomes measurement information system measures into simplified chinese using cognitive interviewing methodology. Cancer Nursing, 2013, 36(5), 368–376.

Haverman, L., Grootenhuis, M. A., Raat, H., van Rossum, M. A. J., van Dulmen-den Broeder, E., Hoppenbrouwers, K., & Terwee, C. B. (2016). Dutch-Flemish translation of nine pediatric item banks from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Quality of Life Research, 25, 761–765.

Terwee, C. B., Roorda, L. D., de Vet, H. C. W., Westhovens, R., van Leeuwen, J., Cella, D., Correia, H., Arnold, B., Perez, B., & Boers, M. (2014). Dutch-Flemisch translation of 17 item banks from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Quality of Life Research, 23(6), 1733–1734.

Bonomi, A. E., Cella, D. F., Hahn, E. A., Bjordal, K., Sperner-Unterweger, B., Gangeri, L., Bergman, B., Wilems-Groot, J., Hanquet, P., & Zittoun, R. (1996). Multilingual translation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy (FACT) Quality of Life measurement system. Quality of Life Research, 5(3), 309–320.

Conway, K., Acquadro, C., & Patrick, D. L. (2014). Usefulness of translatability assessment: Results from a retrospective study. Quality of Life Research, 23(1), 199–210.

Swaine-Verdier, A., Doward, L. C., Hagell, P., Thorsen, H., & McKenna, S. P. (2004). Adapting Quality of Life instruments. Value in Health, 7(Suppl 1), 27–30.

Hurtado, M. P., Angeles, J., Blahut, S. A., & Hays, R. D. (2005). Assessment of the equivalence of the Spanish and English Versions of the CAHPS® hospital survey on the quality of inpatient care. Health Services Research, 40, 2140–2161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00469.x.

Hays, R. D., Calderon, J. L., Spritzer, K. L., Reise, S. P., & Paz, S. H. (2018). Differential item functioning by language on the PROMIS physical functioning items for children and adolescents. Quality of Life Research, 27(1), 235–247.

Nagl, M., Gramm, L., Heyduck, K., Glattacker, M., & Farin, E. (2013). Development and psychometric evaluation of a German version of the PROMIS ® item banks for satisfaction with participation. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 38(2), 160–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278713503468.

Jakob, T., Nagl, M., Gramm, L., Heyduck, K., Farin, E., & Glattacker, M. (2015). Psychometric properties of a German translation of the PROMIS® depression item bank. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 40(1), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278715598600.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joanie Jean for her extensive contributions in summarizing the data and Veronika Ottová-Jordan for her help in editing the manuscript. Furthermore, we thank the translation team, the experts, and all children/adolescents participating in the translation process.

Funding

This PROMIS work was funded by the National Institutes of Health through the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, 1 U01 AR057956-02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The Principal Investigators of this study were Prof. C. Forrest (U.S.) and Prof. U. Ravens-Sieberer (Germany) leading the translation process. Researchers overseeing and conducting the translation process were J. Moon, F. Klasen, J. Devine (German team), and M. Herdman, M.P. Hurtado, and G. Castillo, (Spanish team). The first and second authors wrote this manuscript. All co-authors read, revised, added their comments, discussed, and finally approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. More Information on the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) can be found at http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/ and http://www.nihpromis.org.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Devine, J., Klasen, F., Moon, J. et al. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of eight pediatric PROMIS® item banks into Spanish and German. Qual Life Res 27, 2415–2430 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1874-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1874-8