Abstract

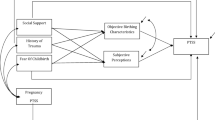

This study examined the incidence of PTSD and psychiatric co-morbidity among women who experienced stillbirth and investigated the relationship between locus of control, trauma characteristics of stillbirth, posttraumatic cognitions, PTSD and co-morbid psychiatric symptoms following stillbirth. Fifty women recorded information on stillbirth experiences, and completed the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale, General Health Questionnaire-28, Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale, Rotter’s Locus of Control Scale and the Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory. 60, 28 and 12 % met the diagnostic criteria for probable full-PTSD, partial and no-PTSD respectively. Sixty-two percent and 54 % scored at or above the cutoff of the General Health Questionnaire-28 and postnatal depression respectively. Women who experienced stillbirth reported significantly more psychiatric co-morbid and post-natal depressive symptoms than the comparison group. Both groups were similar in locus of control. Women who experienced stillbirth reported negative cognitions about the self the most. After adjusting for postnatal depression, trauma characteristics were significantly correlated with Posttraumatic cognitions which, in turn, were significantly correlated with PTSD and psychiatric co-morbidity. Locus of control was not significantly correlated with psychological outcomes. Mediational analyses showed that negative cognitions about self mediated the relationship between trauma characteristics and psychiatric co-morbidity only. Women reported a high incidence of probable PTSD and co-morbid psychiatric symptoms following stillbirth. Stillbirth trauma characteristics influenced how they negatively perceived themselves. This then specifically influenced general psychological problems rather than PTSD symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Engelhard IM, van den Hout MA, Arntz A.: Posttraumatic stress disorder after pregnancy loss. General Hospital Psychiatry 23:62–66, 2001.

Giannandrea SAM, Cerulli C, Anson E, Chaudron LH.: Increased risk for postpartum psychiatric disorders among women with past pregnancy loss. Journal of Women’s Health 22:760–768, 2013.

Turton P, Evans C, Hughes P.: Long-term psychosocial sequelae of stillbirth: Phase II of a nested case-control cohort study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 12:35–41, 2009.

Turton P, Hughes P, Evans CDH, Fainman D.: Incidence, correlates and predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder in the pregnancy after stillbirth. The British Journal of Psychiatry 178:556–560, 2001.

Hughes P, Turton P, Hopper E, Evans CDH.: Assessment of guidelines for good practice in psychosocial care of mothers after stillbirth: A cohort study. Lancet 360:114–18, 2002.

Cacciatore J.: Effects of support groups on post traumatic stress responses in women experiencing stillbirth. OMEGA. 55:71–90, 2007.

Cacciatore J, Schnebly S, Froen JF.: The effects of social support on maternal anxiety and depression after stillbirth. Health and Social Care in the Community 17:167–176, 2009.

Crawley R, Lomax S, Ayers S.: Recovering from stillbirth: the effects of making and sharing memories on maternal mental health. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 31:195–207, 2013.

Ehlers A, Clark DM.: A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research Therapy 38:319–45, 2000.

Costa PT, McCrae RR. Personality: Another ‘hidden factor’ in stress research. Psychological Inquiry 1:22–24, 1990.

Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S.: Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 103:103–116, 1994.

Miller MW.: Personality and the etiology and expression of PTSD: A three-factor model perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 10:373–393, 2003.

Engelhard IM, van den Hout MA, Schouten EGW.: Neuroticism and low educational level predict the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in women after miscarriage or stillbirth. General Hospital Psychiatry 28:414–417, 2006.

Rotter JB.: Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs 80:1–23, 1966.

Klock SC, Chang G, Hiley A, Hill J.: Psychological distress among women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Psychosomatics 38:503–507, 1997.

Jind L.: Parents’ adjustment to late abortion, stillbirth or infant death: The role of causal attributions. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 44:383–394, 2003.

Foa EB, Ehlers A, Clark DM, Tolin DF, Orsillo SM.: The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment 11:303–314, 1999.

Lancaster SL, Rodriguez BF, Weston R.: Path analysis examination of a cognitive model of PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 49:194–201, 2011.

Belsher BE, Ruzek JI, Bongar B, Cordova MJ.: Social constraints, posttraumatic cognitions, and posttraumatic stress disorder in treatment-seeking trauma survivors: Evidence for a social-cognitive processing model. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy 4:386–391, 2012.

Cieslak R, Benight CC, Lehman VC.: Coping self-efficacy mediates the effects of negative cognitions on posttraumatic distress. Behaviour Research and Therapy 46:788–798, 2008.

Daie-Gabai A, Aderka IM, Allon-Schindel I, Foa EB, Gilboa-Schechtman E.: Posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Psychometric properties and gender differences in an Israeli sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 25:266–271, 2011.

Su YJ, Chen SH.: A three-month prospective investigation of negative cognitions in predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms. The mediating role of traumatic memory quality. Chinese Journal of Psychology 50:167–186, 2008.

Blain LM, Galovski TE, Elwood LS, Meriac JP.: How does the posttraumatic cognitions inventory fit in a four-factor posttraumatic stress disorder world? An initial analysis. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy 5:513–520, 2013.

Nixon RDV, Nishith P.: September 11 attacks: Prior interpersonal trauma, dysfunctional cognitions and trauma response in a Midwestern University Sample. Violence and Victims 20:471–480, 2005.

Startup M, Makgekgenene L, Webster R.: The role of self-blame for trauma as assessed by posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): A self-protective cognition? Behaviour Research and Therapy 45:395–403, 2007.

O’Donnell ML, Elliott P, Wolfgang BJ, Creamer M.: Posttraumatic appraisals in the development and persistence of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress 20:173–182, 2007.

Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K.: The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder. The posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychological Assessment 9:445–451, 1997.

Goldberg D, Hillier V.: A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychological Medicine 9:139–145, 1979.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R.: Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 150:782–786, 1987.

Carpenter L, Chung MC.: Childhood trauma in obsessive compulsive disorder: The roles of alexithymia and attachment. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 84:367–388, 2011.

Chung MC, Dennis I, Berger Z, Jones R, Rudd H.: Posttraumatic stress disorder following myocardial infarction: Personality, coping and trauma exposure characteristics. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 42:393–419, 2011.

Hunkin V, Chung MC.: Chronic idiopathic urticaria, psychological co-morbidity and posttraumatic stress: The impact of alexithymia and repression. Psychiatric Quarterly 83:431–447, 2012.

Chin WW, Newsted PR: Structural Equation Modelling Analysis with Small Samples Using Partial Least Squares. In: Hoyle R, (ed) Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research. London, Sage, pp. 307–341, 1999.

Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, Forde DR.: Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1114–11149, 1997.

Chin WW: PLS-Graph User’s Guide. Houston.: Bauer College of Business: University of Houston, 2001.

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH: Psychometric Theory. New York, McCraw-Hill, 1994.

Fornell C, Cha J: Partial least squares. In: Bagozzi RP (Ed) Advanced Methods of Marketing Research. Cambridge, Basil Blackwell, pp. 52–78, 1994.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF.: Asymptotic and resamplying strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40:879–891, 2008.

Calhoun PS, Hertzberg JS, Kirby AC, Dennis MF, Hair LP, Dedert EA, et al. The effect of draft DSM-V criteria on posttraumatic stress disorder prevalence. Depression and Anxiety 29:1032–1042, 2012.

Mosher CE, Danoff-Burg S.: A review of age differences in psychological adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 23:101–114, 2005.

Scott SB.:A lifespan perspective on terrorism: Age differences in trajectories of response to 9/11. Developmental Psychology 49:986–998, 2013.

Macdonald A, Greene CJ, Torres JG, Frueh BC, Morland LA.: Concordance between clinician-assessed and self-reported symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder across three ethnoracial groups. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 5:201–208, 2013.

Miller MW, Kaloupek DG, Dillon AL, Keane TM.: Externalizing and internalizing subtypes of combat related PTSD: A replication and extension using the PSY-5 scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 112:636–45, 2004.

Keane TM, Brief DJ, Pratt EM, Miller MW. Assessment of PTSD and its comorbidities in adults. In: Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA (Eds): Handbook of PTSD. New York, The Guilford Press, pp. 279–305, 2007.

Briere J: Psychological Assessment of Adult Posttraumatic Stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2004.

Gravensteen IK, Helgadόttir LB, Jacobsen EM, Rådestad I, Sandset PM, Ekeberg O.: Women’s Experiences in Relation to Stillbirth and Risk Factors for Long-Term Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms: A Retrospective Study. BMJ Open 3. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003323.

Amir N, Stafford J, Freshman MS, Foa FB.: Relationship between trauma narratives and trauma pathology. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 11:385–392, 1998.

Foa EB, Meadows EA: Psychosocial Treatments for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Critical Review. In: J.Spence, J.M.Darley, D.J.Foss (Eds) Psychosocial Treatments for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Critical Review. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews, pp. 449–480, 1997.

Foa EB, Riggs DS. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder In Rape Victims. In: J.Oldham MBR, Tasman A (Eds) American Psychiatric Press Review of Psychiatry. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, pp. 285–309, 1993.

Soet JE, Brack GA, DiIorio C.: Prevalence and predictors of women’s experience of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care 30:36–46, 2003.

Brewin CR (Ed): Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Malady or Myth? New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Bandura A (Ed): Self-Efficacy. New York, W.H.Freeman & Company, 1997.

Benight CC, Bandura A.: Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy 42:1129–1148, 2004.

Norris FH, Slone LB. The Epidemiology of Trauma and PTSD. In: Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA (Eds): Handbook of PTSD. New York, The Guilford Press, pp. 78–98, 2007.

Hamama L, Rauch SAM, Sperlich M, Defever E, Seng JS.: Previous experience of spontaneous or elective abortion and risk for posttraumatic stress and depression during subsequent pregnancy. Depression and Anxiety 27:699–707, 2010.

Acknowledgments

We thank the women in this study for their participation which made this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicting interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was sought from patients before they commenced the study. Ethical approval for the present study was granted by the research committee at the University of Plymouth.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, M.C., Reed, J. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Following Stillbirth: Trauma Characteristics, Locus of Control, Posttraumatic Cognitions. Psychiatr Q 88, 307–321 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-016-9446-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-016-9446-y