Abstract

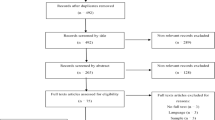

The quality of parenting is recognised as an important determinant of children’s mental health. Parenting interventions typically target high-risk families rather than adopting a universal approach. This study examined the population impact of the Triple P Positive Parenting Programme on the prevalence of children’s social, emotional, and behavioural problems. A propensity score matching difference-in-differences method was used to compare intervention and comparison regions matched on socio-demographic characteristics in midlands Ireland. The pre-intervention sample included 1501 and 1495 parents of children aged 4–8 years in the intervention and comparison regions respectively. The post-intervention sample included 1521 and 1544 parents respectively. The primary outcome measure was parental reports on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. There were some significant reductions in the prevalence rates of social, emotional, and behavioural problems in the intervention regions compared to the comparison regions. Children in the intervention sample experienced lower total difficulties, emotional symptoms, and conduct problems than children in the comparison sample, and they were less at risk of scoring within the borderline/abnormal range for total difficulties, conduct problems, and hyperactivity. The programme reduced the proportion of children scoring within the borderline/abnormal range by 4.7% for total difficulties, 4.4% for conduct problems, and 4.5% for hyperactivity in the total population. This study demonstrated that a universal parenting programme implemented at multiple levels using a partnership approach may be an effective population health approach to targeting child mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ashenfelter, O., & Card, D. (1985). Using the longitudinal structure of earnings to estimate the effect of training programs. The Review of Economic Statistics, 67, 648–660.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc..

Bandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing society. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Barlow, J., Parsons, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2002). Systematic review of the effectiveness of parenting programmes in the primary and secondary prevention of mental health problems. Oxford: Health Services Research Unit, University of Oxford.

Bayer, J. K., Hiscock, H., Ukoumunne, O. C., Price, A., & Wake, M. (2008). Early childhood aetiology of mental health problems: A longitudinal population-based study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 1166–1174.

Caliendo, M., & Kopeinig, S. (2008). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22, 31–72.

Davis, E., Sawyer, M. G., Lo, S. K., Priest, N., & Wake, M. (2010). Socioeconomic risk factors for mental health problems in 4-5-year-old children: Australian population study. Academic Pediatrics, 10, 41–47.

DuGoff, E. H., Schuler, M., & Stuart, E. A. (2014). Generalizing observational study results: Applying propensity score methods to complex surveys. Health Services Research, 49, 284–303.

Ermisch, J. (2008). Origins of social immobility and inequality: Parenting and early child development. National Institute Economic Review, 205, 62–71.

Farrar, S., Yi, D., Sutton, M., Chalkley, M., Sussex, J., & Scott, A. (2009). Has payment by results affected the way that English hospitals provide care? Difference-in-differences analysis. British Medical Journal, 339, b3047.

Fives, A., Pursell, L., Heary, C., Nic Gabhainn, S., & Canavan, J. (2014). Parenting support for every parent: A population-level evaluation of Triple P in Longford Westmeath. Final Report. Retrieved from Athlone: www.mapp.ie.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute: The National Implementation Research Network (FMHI Publication #231).

Foster, E. M., Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., & Shapiro, C. J. (2008). The costs of a public health infrastructure for delivering parenting and family support. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 493–501.

Gardner, F., & Shaw, D. S. (2008). Behavioral problems of infancy and preschool children (0–5). In M. Rutter, D. Bishop, D. Pine, S. Scott, J. Stevenson, E. Taylor, & A. Thapar (Eds.), Rutter’s child and adolescent psychiatry (pp. 882–893). Oxford: Blackwell.

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586.

Goodman, A., Joyce, R., & Smith, J. P. (2011). The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 108, 6032–6037.

Gueorguieva, R., & Krystal, J. H. (2004). Move over ANOVA: Progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the archives of general psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 310–317.

Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. E. (1997). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme. The Review of Economic Studies, 64, 605–654.

Kakil, A. (2013). Effects of the great recession on child development. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 650, 232–249.

Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 567–589.

Kato, N., Yanagawa, T., Fujiwara, T., & Morawska, A. (2015). Prevalence of children’s mental health problems and the effectiveness of population-level family interventions. Journal of Epidemiology, 25, 507–516.

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., Boyce, T., McNeish, D., Grady, M., & Geddes, I. (2010). Fair society, healthy lives: The marmot review. London: Department of Health.

Marryat, L., Thompson, L., & Wilson, P. (2017). No evidence of whole population mental health impact of the Triple P programme: Findings from a routine dataset. BMC Pediatrics, 17, 40.

Miner, J. L., & Clarke-Stewart, K. (2008). Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: Relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Developmental Psychology, 44, 771–786.

Owens, C., Heavey, K., Hegarty, M., Clarke, J., Burke, K., & Owens, S. (2016). Triple-P-implementation guide. Retrieved from Athlone: www.mapp.ie.

Owens, C., Doyle, O., Hegarty, M., Heavey, K., & Farrell, E. (2018). Partnerships and scaling up population level interventions. In M. Sanders & T. G. Mazzucchell (Eds.), The power of positive parenting: Transforming the lives of children, parents, and communities using the Triple P System. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Eugene: Castalia Press.

Pickering, J., & Sanders, M. (2015). The Triple P-positive parenting program: An example of a public health approach to evidence-based parenting support. Family Matters, 96, 53.

Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science, 10, 1–12.

Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2016). Addendum to “Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial”. Prevention Science, 17, 410–416.

Sanders, R. M. (1996). New Directions in behavioural family interventions with children. In T. H. Ollendick & R. J. Prinz (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology (Vol. 18, pp. 283–330). New York: Plenum Press.

Sanders, M. R. (2003). Triple P-positive parenting program: A population approach to promoting competent parenting. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 2, 127–143.

Sanders, M. R. (2008). Triple P-positive parenting program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 506–517.

Sanders, R. M., Markie-Dadds, & Turner, K. (2004). Using the Triple P system of intervention to prevent behavioural problems in children and adolescents. In P. M. Barrett & T. H. Ollendick (Eds.), Handbook of interventions that work with children and adolescents: Prevention and treatment. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Sanders, M. R., Ralph, A., Sofronoff, K., Gardiner, P., Thompson, R., Dwyer, S., & Bidwell, K. (2008). Every family: A population approach to reducing behavioral and emotional problems in children making the transition to school. Journal of Primary Prevention, 29, 197–222.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Garner, A. S. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246.

Stone, L. L., Otten, R., Engels, R. C. M. E., Vermulst, A. A., & Janssens, J. M. A. M. (2010). Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4- to 12-year-olds: A review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 254–274.

Stuart, E. A., Huskamp, H. A., Duckworth, K., et al. (2014). Using propensity scores in difference-in-differences models to estimate the effects of a policy change. Health Services Outcomes Research Methodology, 14, 166–182.

Tremblay, R. E. (2010). Developmental origins of disruptive behaviour problems: The ‘original sin’ hypothesis, epigenetics and their consequences for prevention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 341–367.

Villa, J. (2016). Simplifying the estimation of difference-in-differences treatment effects. The Stata Journal, 16, 52–71.

Washington State Institute for Public Policy. (2012). Return on investment: Evidence-based options to improve statewide outcomes. Retrieved from http://www.wsipp.wa.gov.

Zanutto, E. L. (2006). A comparison of propensity score and linear regression analysis of complex survey data. Journal of Data Science, 4, 67–91.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating families and partnership members (Athlone Community Services Council, Athlone Education Centre, Carrick-on-Shannon Education Centre, Health Service Executive (Primary Care and Health and Wellbeing Directorates), Longford Community Resources Limited, Longford Vocational Educational Committee, TUSLA Child and Family Agency, Westmeath Community Development, Westmeath County Childcare Committee). We acknowledge the NUIG research team of Saoirse Ni Gabhainn, John Canavan, Allyn Fives, Lisa Pursell, and Catherine Heary for their help in the population study methodology design and inputting of data. Data in the population survey were collected by two market research agencies, Millward Brown and Amarach. We also acknowledge the support and guidance offered by critical friends, The Atlantic Philanthropies and their Expert Advisory Committee, the Centre for Effective Services, Archways, Phil Jennings, Danny Perkins, and especially, the commitment, skill, and passion of the Triple P practitioners.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from The Atlantic Philanthropies, the Irish Government’s Department of Children and Youth Affairs, the Irish Health Service Executive, and Tusla. The funders did not have any role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; nor the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The submitted work was supporting by The Atlantic Philanthropies, the Irish Government’s Department of Children and Youth Affairs, the Irish Health Service Executive, and Tusla. Owens and Hegarty are employees of the Health Service Executive and the Longford/Westmeath Parenting Partnership; Owens was responsible for delivering the Triple P programme, and Doyle was a consultant for the Longford/Westmeath Parenting Partnership.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval for data collection was granted by the National University of Ireland (NUI) Galway’s Research Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 63 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doyle, O., Hegarty, M. & Owens, C. Population-Based System of Parenting Support to Reduce the Prevalence of Child Social, Emotional, and Behavioural Problems: Difference-In-Differences Study. Prev Sci 19, 772–781 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0907-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0907-4