Abstract

The development of political engagement in early life is significant given its impact on political knowledge and participation. Analyses reveal a large influence of parents on their offspring’s curiosity about politics during their teenage years. Increasingly, civic education is also considered an important influence on political interest and orientations of young people as schools are assigned a crucial role in creating and maintaining civic equality. We study the effects of civic education on political engagement, focusing especially on whether and how civic education can compensate for missing parental political socialization. We use data from the Belgian Political Panel Study (2006–2011) and the U.S. Youth-Parent Socialization Panel Study (1965–1997), which both contain information on political attitudes and behaviors of adolescents and young adults, those of their parents, and on the educational curriculum of the young respondents. Our findings suggest that civics training in schools indeed compensates for inequalities in family socialization with respect to political engagement. This conclusion holds for two very different countries (the U.S. and Belgium), at very different points in time (the 1960s and the 2000s), and for a varying length of observation (youth to old age and impressionable years only).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Humphries, Muller, and Schiller (2013) reported that the academic rigor of high school course work (but not the number of social science credits) had a greater positive effect on the likelihood of registering to vote for Latino children of immigrants than among white third-generation-plus young adults.

A study of a political event (specifically a U.S. presidential campaign) also showed mixed evidence – a kind of compensation with respect to candidate evaluations (Sears and Valentino 1997, 56-57).

Hooghe and Dassonneville interacted students’ initial knowledge levels and classroom characteristics, thus looking only indirectly at compensation for limited family socialization.

Since parental socialization processes already occur before young people are exposed to civic education classes, our general expectation is that those from families with high levels of socialization have the highest starting levels of political engagement, whereas those from less politicized backgrounds have the lowest starting levels of civic education.

Belgium is an established democracy that offers a common core curriculum to pupils in secondary education, as is true for many other European countries (European Commission 2014). It is, moreover, unexceptional in Europe with regard to the level and development of political engagement (Torney-Purta 2002). We thus have no reason to believe that Belgium would be an unusual case with respect to civic education, which is in the focus of this study.

The main reason for requiring participation in all three waves is a methodological one, as it is required by our modeling strategy – latent growth curve modeling. This means, however, that we only work with 44.6 % of the original sample. In the online Appendix I, we compare the demographic attributes, civic education scores, parental socialization, and the mean dependent variable for those who dropped out of the panel in either 2008 or 2011 and those who remained in the panel throughout all three waves. The main and significant differences relate to the demographic attributes (see also Hooghe et al. 2011, 16). Those who dropped out of the panel were on average 5 months older in 2006. Also, more boys and respondents from Wallonia dropped out. Further, those who remained in the panel had higher educational aspirations (37 % aimed to go to university in 2006, compared to only 25 % of those that dropped out of the panel). Our models control for all these variables, which makes it less problematic that the three-wave panel is somewhat less representative than the initial wave. Regarding the key variables (civic education scores, parental socialization, and civic engagement), the differences between the two samples are very small and negligible. We therefore do not believe that panel attrition affects our conclusions.

See Ansolabehere et al. (2008) for more on the advantages of using indexes to measure attitudes and behavior.

A factor analysis confirmed that all three items load very strongly on only one dimension (Eigenvalue: 2.387; proportion: 0.478). To make sure that using an index as a dependent variable does not influence our results, we also estimated our models with the single independent variables (political news consumption, political interest, and political discussion). The results are presented in Appendix F in Supplementary Material and are largely the same as those presented in results section below.

As discussed in the methods section below, we are modelling the change in the dependent variable as respondents age. We treat the initial parental socialization and civic education as the starting points that (at least partly) predict the initial level of political engagement observed in the 2006 wave, when respondents were between 14 and 20 years old (average = 15.7).

Students are clustered in 337 classes in 108 schools. There are between 1 and 47 pupils per class, with an average of 14 pupils per class. Using the average score of civic education per class accounts for measurement error, as it is expected that some students under- or over-report the amount and content of their civic education. See Dassonneville et al. (2012) for more on this topic. In order to assess whether the civic education measures are affected by varying reliability due to changing class sizes, we replicated our models with those in classes of at least 10 pupils. Appendix H in Supplementary Material reports the results of these models, which are based on 1485 pupils in 110 classes. The substantive conclusions remain the same.

We refrained from putting the three indicators into an index measuring active learning. First, each item taps different forms of active learning, some being explicitly political (visits to the parliament and from politicians) and others being very unspecific (group work). Second, as the alpha coefficient of 0.04 indicates, these items are empirically unrelated.

We decided to capture the average educational attainment of the parents rather than including the education of the mother and the father separately. First, the education of the parents is reported by the children themselves. We hence hope that by averaging the education of the parents, we account for possible over- or under-reporting. Second, the education of parents is highly correlated (r = 0.54) and we hence feel confident that we capture a family status rather than a maternal or paternal influence only. We nevertheless ran the models separately for mothers’ and fathers’ education and find the same, insignificant, effects as for the combined parental education. The results are available upon request from the authors.

While the educational tracks in Flanders and Wallonia are slightly different, in general, there are three different tracks in the Belgian secondary education system: a vocational, a technical, and a general track. Anyone with a secondary education diploma is free to enroll in post-secondary education. However, those taking the vocational track have to take an extra year in post-secondary education. Moreover, the success rate for those coming from vocational and technical tracks is lower than for those from the general track, which prepares students for higher education (not surprisingly, this is also related to factors such as socio-economic status). We categorized the educational track variable into a dummy, as the tracks below the general secondary education track differ slightly between Flanders and Wallonia and a more nuanced distinction is therefore problematic.

As a robustness check, we also estimated our growth models as a function of time instead of as a function of age. The results are presented in Appendix G in Supplementary Material and show very few differences to the models estimated with age. We present the models with growth as a function of age in the remainder of this paper, as the theoretical expectation is that levels of political engagement increase with the life experiences that accompany the ageing process.

We assume a fixed (linear) parameterization of the growth function of political engagement during the (pre-)adulthood years, which is partially due to data restrictions and partially for theoretical reasons. Bollen and Curran (2006) show that three waves are the minimum requirement for testing a linear model (see also the more recent study by Little 2013). In any event, Prior (2010) and Neundorf et al. (2013) found that the growth of political engagement between ages 17-25 is linear and then flattens or stabilizes.

Note that we include only respondents who answered all questions in our models. We report the results of the full sample in Appendix E in Supplementary Material. Reducing the sample to 6565 observations (i.e., 2190 respondents over three time points) does not change the results.

We additionally estimated the models separately for parental socialization and civic education rather than estimating both sets of variables together. The results are generally the same and are available upon request from the authors.

We estimated a log-likelihood ratio test for all models. Including the fixed-effects on the intercept as well as including the random effects on the slope coefficients significantly improves the model compared to Model 1, which simply models the mean growth parameters for each respondent.

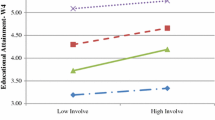

All nine corresponding figures of predicted values based on the results in Table 3 are presented in Appendix D in Supplementary Material.

The exact question wording of the variables is reported in Appendix J in Supplementary Material. To measure political engagement, we used political interest and news consumption only. Unlike in the BPPS, there was no comparable measure for political discussion over time, which was hence not included in the index. We measure parental socialization using frequency of discussion with family about public affairs. We did not include parental education, which did not prove to be of significance in the Belgian or the U.S. models. There was no question about the number of books in the home.

Note that the average political discussion with the parents in the U.S. in 1965 is much higher than in Belgium in 2006 (mean: 1.7). Both variables are measured on a scale 1 to 4, where 4 represents almost daily political discussions at home. Similarly, the average political engagement in the U.S. in 1965 among high school seniors is 3.15 (on a scale of 1 to 4), compared to 2.65 (on a scale 1 to 5) in Belgium in 2006. Based on these and other comparable measures, it appears that generally today’s youth in numerous countries is much less political than previous generations were, at least on conventional activities (e.g., Howe 2010, Wattenberg 2012).

References

Alford, J. R., Funk, C. L., & Hibbing, J. R. (2005). Are political orientations genetically transmitted? American Political Science Review, 99(2), 153–167.

Ansolabehere, S., Rodden, J., & Snyder, J. M, Jr. (2008). The strength of issues: using multiple measures to gauge preference stability, ideological constraint, and issue voting. American Political Science Review, 102(2), 215–232.

Bartels, L. M., & Jackman, S. (2014). A generational model of political learning. Electoral Studies, 33, 7–18.

Bollen, K. A., & Curran, P. J. (2006). Latent curve models. A structural equation perspective. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Campbell, D. (2008). Voice in the classroom: How an open classroom climate fosters political engagement among adolescents. Political Behavior, 30(4), 437–454.

Campbell, D. (2009). Civic engagement and education: An empirical test of the sorting model. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 771–786.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Campbell, D., & Niemi, R. G. (2015). Teaching citizenship: State-level civic education requirements and political knowledge. American Political Science Review, forthcoming.

Chaffee, S. H., Morduchowicz, R., & Galperin, H. (1998). Education for democracy in Argentina: Effects of a newspaper-in-school program. In O. Ichilov (Ed.), Citizenship and citizenship education in a changing World. London: Woburn.

Commission, European. (2014). The structure of the European education systems 2014/15: Schematic diagrams. Brussels: The European Commission.

Dassonneville, R., Quintelier, E., Hooghe, M., & Claes, E. (2012). The relation between civic education and political attitudes and behavior: A two-year panel study among Belgian late adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 16(3), 140–150.

Evans, M. D. R., Kelley, J., Sikora, J., & Treiman, D. J. (2010). Family scholarly culture and educational success: Evidence from 27 nations. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 28(2), 171–197.

Finlay, A., Wray-Lake, L., & Flanagan, C. A. (2010). Civic engagement during the transition to adulthood: Developmental opportunities and social policies at a critical juncture. In L. Sherrod, J. Torney-Purta, & C. A. Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Gainous, J., & Martens, A. M. (2012). The effectiveness of civic education: Are “good” teachers actually good for students? American Politics Research, 40(2), 232–266.

Galston, W. A. (2001). Political knowledge, political engagement, and civic education. Annual Review of Political Science, 4, 217–234.

Guardian of democracy: The civic mission of schools. (2011). Retrieved from www.civicmissionofschools.org.

Händle, C., Oesterreich, D., & Trommer, L. (1999). Concepts of civic education in Germany based on a survey of expert opinion. In J. Torney-Purta, J. Schwille, & J. Amadeo (Eds.), Civic education across countries: Twenty-four national case studies from the IEA civic education project. Amsterdam: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

Hooghe, M., & Dassonneville, R. (2011). The effects of civic education on political knowledge. A two year panel survey among Belgian adolescents. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 23(4), 321–339.

Hooghe, M., Dassonneville, R., & Marien, S. (2015). The impact of education on the development of political trust. Results from a five year panel study among late adolescents and young adults in Belgium. Political Studies, 63(1), 123–141.

Hooghe, M., Havermans, N., Quintelier, E., & Dassonneville, R. (2011). Belgian political panel survey (BPPS), 2006–2011 Technical Report. Leuven: K.U. Leuven.

Howe, P. (2010). Citizens adrift: The democratic disengagement of young Canadians. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Humphries, M., Muller, C., & Schiller, K. S. (2013). The political socialization of adolescent children of immigrants. Social Studies Quarterly, 94(5), 1261–1280.

Hyman, H. (1959). Political socialization. New York: Free Press.

Jennings, M. K., Markus, G. B., Niemi, R. G., & Stoker, L. (2005). Youth-parent socialization panel Study, 1965–1997: Four waves combined. ICPSR04037-v1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2005-11-04. doi:10.3886/ICPSR04037.v1.

Jennings, M. K., & Niemi, R. G. (1968). The transmission of political views from parent to child. American Political Science Review, 62(1), 169–181.

Jennings, M. K., & Niemi, R. G. (1981). Generations and politics: A panel study of young adults and their parents. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jennings, M. K., Stoker, L., & Bowers, J. (2009). Politics across generations: Family transmission reexamined. Journal of Politics, 71(3), 782–799.

Kisby, B., & Sloam, J. (2012). Citizenship, democracy and education in the UK: Towards a common framework for citizenship lessons in the four home nations. Parliamentary Affairs, 65(1), 68–89.

Kroh, M., & Selb, P. (2009). Inheritance and the dynamics of party identification. Political Behavior, 31(4), 559–574.

Langton, K. P., & Jennings, M. K. (1968). Political socialization and the high school civics curriculum in the United States. American Political Science Review, 62(3), 852–867.

Levine, P. (2007). The Future of democracy: Developing the next generation of American citizens. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England.

Levinson, M. (2012). No citizen left behind. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modelling. New York: Guilford.

Martens, A. M., & Gainous, J. (2013). Civic education and democratic capacity: How do teachers teach and what works? Social Science Quarterly, 94(4), 956–976.

Neundorf, A., Smets, K., & García Albacete, G. M. (2013). Homemade citizens: The development of political interest during adolescence and young adulthood. Acta Politica, 48(1), 92–116.

Nie, N. H., & Hillygus, D. S. (2001). Education and democratic citizenship. In D. Ravitch & J. P. Viteritti (Eds.), Making good citizens: education and civil society. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Nie, N. H., Junn, J., & Stehlik-Barry, K. (1996). Education and democratic citizenship in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Niemi, R. G., & Junn, J. (1998). Civic education: What makes students learn. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Persson, M. (2014). Testing the relationship between education and political participation using the 1970 British cohort study. Political Behavior, 36(4), 877–897.

Persson, M. (2015). Classroom climate and political learning: Findings from a Swedish panel study and comparative data. Political Psychology, 36(5), 587–601.

Preacher, K. J., Wichman, A. L., & MacCallum, R. C. (2008). Latent growth curve modeling. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences (Vol. 07-157). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Prior, M. (2010). You either got it or you don’t? The stability of political interest over the life-cycle. Journal of Politics, 72(3), 747–766.

Sears, D., & Valentino, N. (1997). Politics matters: Political events as catalysts for preadult socialization. American Political Science Review, 91(1), 45–65.

Torney-Purta, J. (2002). The school’s role in developing civic engagement: A study of adolescents in twenty-eight countries. Applied Developmental Science, 6(4), 203–212.

Van Ingen, E., & van der Meer, T. (2016). Schools or pools of democracy? A longitudinal test of relation between civic participation and political socialization. Political Behavior, 38(1), 83–103.

Wattenberg, M. (2012). Is voting for young people? (3rd ed.). New York: Pearson.

Westholm, A., & Niemi, R. G. (1992). Political institutions and political socialization: A cross-national study. Comparative Politics, 25(1), 25–41.

Zuckerman, A. S., Dasović, J., & Fitzgerald, J. (2007). Partisan families: The social logic of bounded partisanship in Germany and Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zukin, C., Keeter, S., Andolina, M., Jenkins, K., & Delli Carpini, M. X. (2006). A new engagement? Political participation, civic life, and the changing American citizen. New York: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

The supplementary material, the code to replicate the recoding of the data and model estimation, as well as the data of the Belgian Political Panel Study (BPPS) can be downloaded from www.aneundorf.net/Publications. The data of the U.S. Youth-Parent Socialization Panel Study can be accessed from the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center and Center for Political Studies (ICPSR, study number 4037): http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04037.v1. We would like to thank Marc Hooghe and his team for allowing us to use the BPPS dataset. Special thanks go to Ruth Dassonneville and Ellen Quintelier for answering our many queries in relation to the BPPS project. We presented earlier drafts of this paper at the following workshops and conferences: the 12th Dutch-Flemish Political Science Conference Politicologenetmaal (Ghent, Belgium, May 30/31, 2013); the workshop “Young people’s politics” (Lincoln, UK, September 5, 2014) organised by the PSA Specialist Group on Young People and Politics; the conference “Inequality of active citizenship: Can education mend the gap?” (London, UK, May 28/29, 2015) organized by LLAKES and AMCIS; as well as the workshop on “The crisis for contemporary youth: opportunities and civic values in comparative, longitudinal and inter-generational perspective” (London, UK, June 4/5, 2015) organized by LLAKES. We would like to thank the panelists for their useful comments. Lastly, we are grateful for the constructive feedback of the three reviewers and the editor of Political Behavior.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neundorf, A., Niemi, R.G. & Smets, K. The Compensation Effect of Civic Education on Political Engagement: How Civics Classes Make Up for Missing Parental Socialization. Polit Behav 38, 921–949 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9341-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9341-0