Abstract

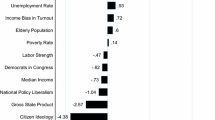

Nearly a half-century ago, E.E. Schattschneider wrote that the high abstention and large differences between the rates of electoral participation of richer and poorer citizens found in the United States were caused by high levels of economic inequality. Despite increasing inequality and stagnant or declining voting rates since then, Schattschneider’s hypothesis remains largely untested. This article takes advantage of the variation in inequality across states and over time to remedy this oversight. Using a multilevel analysis that combines aspects of state context with individual survey responses in 144 gubernatorial elections, it finds that citizens of states with greater income inequality are less likely to vote and that income inequality increases income bias in the electorate, lending empirical support to Schattschneider’s argument.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Intensive case studies of single communities have convincingly documented the process by which particular issues have been kept off of their political agendas (see, e.g., Bachrach and Baratz 1970; Gaventa 1980), but such research designs lack variation in both economic inequality and political participation and so remain only suggestive of the relationships between constrained agendas and these variables. For an impressive demonstration of the relationship across states in the early twentieth century between the concentration of economic power and the consideration and disposition of the single issue of direct-democracy reforms, see Hill and Klarner (2002). Even this work examines what happened only in those states where direct democracy was a matter of public controversy and so sidesteps the troublesome determination of whether citizens elsewhere would have wanted to debate it but, in the face of an elite consensus in opposition, were unable to place it on the political agenda (Hill and Klarner 2002, pp. 1119–1121).

Leighley and Nagler (1992), for example, examined individual participation in seven presidential elections from 1964 to 1988 and concluded that the income bias in the electorate did not change in that time, and Shields and Goidel (1997) found a similar pattern in ten midterm congressional elections. Many others, however, examined similar evidence and reached the opposite conclusion (Piven and Cloward 1988; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Darmofal 1999; Freeman 2004).

For an alternate approach that examines national-level economic inequality and participation from a cross-national comparative perspective, see Solt (2008).

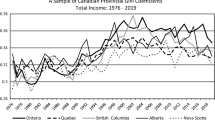

Although income data from the Census Bureau’s March Supplement to the Current Population Survey (CPS) is often used to generate estimates of state-level income inequality between census years, top-coding and other issues with the CPS income data render such estimates of rather low quality: CPS-based inequality measures typically explain scarcely half of the variation across states in Census-based inequality measures for those years when both are available (Langer 1999, p. 60).

Although not measured simultaneously with these elections, which were held in November of the preceding and following years, the available data on household income inequality provide excellent information about the context in which the elections were held because inequality changed only slowly year-to-year. Even the steepest observed change in inequality, that of New York during the 1980s, averaged just 1.1% annually. The mean change in inequality across the states in the period examined was only .6% per year.

Although Mississippi and Louisiana were among the three most unequal states in each census, their absence from the sample does not bias the results of this study; selection bias occurs only when cases are selected in a manner that reduces variation in the dependent variable (King et al. 1994, p. 137).

Absolute and relative income are, of course, conceptually distinct: the same amount of absolute income may be relatively rich or relatively poor given different income distributions and average incomes. They are also distinct empirically. In this dataset, the two variables exhibit a bivariate correlation of .727 and so a variance inflation factor (VIF) of just 2.12; a VIF of 4, indicating that standard errors are doubled, is commonly recognized as the point at which collinearity begins to be problematic (Fox 1991, pp. 10–13). Dropping absolute income from the analysis or replacing it with median income at the state-year level does not substantially affect the results presented.

The CPS data include very few asian american or native american respondents, and their electoral participation was not found to be distinctive; variables identifying individuals of these heritages were therefore omitted from the analysis presented below for the sake of parsimony. Their inclusion does not affect the results obtained for the other variables in the analysis.

An alternate technique for analyzing such nested data, logistic regression analysis with two-way clustered standard errors (here, correcting for the clustering of observations both within elections and within states), provided substantively similar results to those presented here.

The hypothetical “typical citizen” was defined to have median scores on all characteristics included in the model, that is, she was a 42-year-old married white woman with a high school education and median income who owned her non-rural home and had lived there for more than 2 years. The “typical” gubernatorial election was also defined as having median characteristics: it was held in the middle of the presidential term, without any ballot initiatives, 29 days after registration closed, in a non-southern state where there was a 27.7% chance that any two individuals are of different racial or ethnic backgrounds and 17.6% of nonfarm workers were union members, and its margin of victory was 11.4%.

This 95% confidence interval and those for all other quantities of interest were approximated by generating 1,000 values for each of the model parameters from their estimated distributions and using these values to simulate the distribution of the statistic in question (see King et al. 2000). These simulations were performed with Stata 9.2.

Although not presented in full here, separate analyses of gubernatorial elections in presidential years and those held in off-years yielded substantively similar results. For elections held at mid-term, inequality was estimated to reduce the probability of voting for a typical citizen by 17 percentage points, ±11 points, over its observed range when all other variables are held constant at their median values. When the 36 elections held concurrently with presidential contests were considered separately, inequality was estimated to reduce this probability of voting by 14 ± 13 percentage points.

These estimates were generated by assuming median values for all of the other variables in the model except household income. Because household income is related to household income quintile by definition, the mean score of household income within each quintile was used in the simulations. Additional simulations using the overall median household income, however, produced substantively similar results.

When analyzed separately, income bias in midterm gubernatorial elections was estimated to increase from 13% (±3%) to 20% (±4%) over the range of inequality observed in those contests; the income bias in participation in the elections for governor with concurrent presidential races was estimated to increase from 16% (±4%) to 27% (±8%).

References

Achen, C. H., & Shively, W. P. (1995). Cross-level inference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economic Letters, 80, 123–129.

APSA Task Force on Inequality and American Democracy. (2004). American democracy in an age of rising inequality. Perspectives on Politics, 2(4), 651–670.

Bachrach, P., & Baratz, M. S. (1970). Power and poverty: Theory and practice. London: Oxford University Press.

Bachrach, P., & Baratz, M. S. (1975). Power and its two faces revisited: A reply to Geoffrey Debnam. American Political Science Review, 69(3), 900–904.

Bartels, L. M. (2006). Is the water rising? Reflections on inequality and American democracy. PS: Political Science and Politics, 39(1), 39–42.

Bartels, L. M. (2008). Unequal democracy: The political economy of the new gilded age. Princeton, NJ: Russell Sage Foundation and Princeton University Press.

Berry, W. D., Rubin, J. H., & Esarey, J. (2010). Testing for interaction in binary logit and probit models: Is a product term essential? American Journal of Political Science, 54(1), 248–266.

Brady, H. E. (2004). An analytical perspective on participatory inequality and income inequality. In K. M. Neckerman (Ed.), Social inequality (pp. 667–702). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82.

Burnham, W. D. (1965). The changing shape of the American political universe. American Political Science Review, 59(1), 7–28.

Darmofal, D. (1999). Socioeconomic bias in turnout decline: Do the voters remain the same? Presented at Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Atlanta.

Debnam, G. (1975). Nondecisions and power: The two faces of Bachrach and Baratz. American Political Science Review, 69(3), 889–899.

Fox, J. (1991). Regression diagnostics. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Freeman, R. B. (2004). What, me vote? In K. M. Neckerman (Ed.), Social inequality (pp. 703–728). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Frey, F. W. (1971). Comment: On issues and nonissues in the study of power. American Political Science Review, 65(4), 1081–1101.

Gaventa, J. (1980). Power and powerlessness: Quiescence and rebellion in an Appalachian Valley. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gilens, M. (2005). Inequality and democratic responsiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69(5), 778–796.

Hacker, J. S. (2006). Inequality, American democracy, and American political science: The need for cumulative research. PS: Political Science and Politics, 39(1), 47–49.

Hill, K. Q., & Klarner, C. (2002). The many faces of elite power in the ‘System of 1896’. Journal of Politics, 64(4), 1115–1136.

Hill, K. Q., & Leighley, J. E. (1992). The policy consequences of class bias in state electorates. American Journal of Political Science, 36(2), 351–365.

Hill, K. Q., & Leighley, J. E. (1999). Racial diversity, voter turnout, and mobilizing institutions in the United States. American Politics Quarterly, 27(3), 275–295.

Hirsch, B. T., Macpherson, D. A., & Vroman, W. G. (2001). Estimates of union density by state. Monthly Labor Review, 124(7), 51–55.

Huckfeldt, R., & Sprague, J. (1993). Citizens, context, and politics. In A. W. Finifter (Ed.), Political science: The state of the discipline II (pp. 281–303). Washington, DC: American Political Science Association.

Jacobs, L. R., & Page, B. I. (2005). Who influences US foreign policy? American Political Science Review, 99(1), 107–123.

King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 347–361.

Langer, L. (1999). Measuring income distribution across space and time in the American States. Social Science Quarterly, 80(1), 55–67.

Leighley, J. E., & Nagler, J. (1992). Socioeconomic class bias in turnout, 1964–1988: The voters remain the same. American Political Science Review, 86(3), 725–736.

Leighley, J. E., & Nagler, J. (2007). Unions, voter turnout, and class bias in the U.S. electorate, 1964–2004. Journal of Politics, 69(2), 430–441.

Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A radical view (2nd ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Patterson, S. C., & Caldeira, G. A. (1983). Getting out the vote: Participation in gubernatorial elections. American Political Science Review, 77(3), 675–689.

Piven, F. F., & Cloward, R. A. (1988). Why Americans don’t vote. New York: Pantheon.

Polsby, N. W. (1963). Community power and political theory. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rosenstone, S., & Hansen, J. (1993). Mobilization, participation, and democracy in America. New York: Macmillan.

Rosenstone, S. J., & Wolfinger, R. E. (1978). The effect of registration laws on voter turnout. American Political Science Review, 72(1), 22–45.

Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semisovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. New York: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston.

Schlozman, K., Lehman, B. I., Page, S., & Verba, M. F. (2004). Inequalities of political voice. Washington, DC: Task force on inequality and American democracy, American Political Science Association.

Shields, T. G., & Goidel, R. K. (1997). Participation rates, socioeconomic class biases, and congressional elections: A crossvalidation. American Journal of Political Science, 41(2), 683–691.

Silver, B. D., Anderson, B. A., & Abramson, P. R. (1986). Who overreports voting? American Political Science Review, 80(2), 613–624.

Solt, F. (2008). Economic inequality and democratic political engagement. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 48–60.

Steenbergen, M. R., & Jones, B. S. (2002). Modeling multilevel data structures. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 218–237.

Tolbert, C. J., & Smith, D. A. (2005). The educative effects of ballot initiatives on voter turnout. American Politics Research, 33(2), 283–309.

Van Evera, S. (1997). Guide to methods for students of political science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wolfinger, R. E. (1971). Nondecisions and the study of local politics. American Political Science Review, 65(4), 1063–1080.

Wolfinger, R., & Rosenstone, S. (1980). Who votes? New Haven: Yale University Press.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Stephen Bloom, Gina Branton, Tobin Grant, Evelyne Huber, Patrick Kenney, Melissa Marschall, Scott McClurg, Celeste Montoya, Peter Nardulli, Marco Steenbergen, and the editors and reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Solt, F. Does Economic Inequality Depress Electoral Participation? Testing the Schattschneider Hypothesis. Polit Behav 32, 285–301 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9106-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9106-0