Abstract

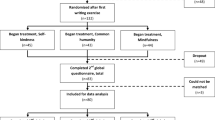

Effects of two meditation and mindfulness-based spiritual interventions were examined in college undergraduates (N=44). Compared to a control group, both interventions decreased negative religious coping (d=−0.80, p<.01) and images of God as mainly controlling (d=−.73, p<.01). One intervention provided more training in tools for learning from community and tradition-based spiritual exemplars. It produced gains in famous or traditional spiritual exemplars’ perceived influence (d=+.81, p<.05) and availability (d=+.66, p<.10), in self-efficacy for learning from spiritual exemplars (d=+.92, p<.05), and in nonmaterialistic aspirations (d=+0.65, p<.05).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alexander, C. N., Langer, E. J., Newman, R. I., Chandler, H. M., & Davies, J. L. (1989). Transcendental meditation, mindfulness, and longevity: An experimental study with the elderly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 950–964.

Astin, J. A. (1997). Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation: Effects on psychological symptomatology, sense of control, and spiritual experiences. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 66, 97–106.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (2003). On the psychosocial impact and mechanisms of spiritual modeling. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 13, 167–174.

Benson, H., & Stark, M. (1997). Timeless healing: The power and biology of belief. New York: Fireside.

Benson, P., & Spilka, B. (1973). God image as a function of self-esteem and locus of control. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 12, 297–310.

Cahn, B. R., & Polich, J. (2006). Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 180–211.

Casey, M., Monk of Tarrawarra. (1996). Sacred reading: The ancient art of lectio divina. Liguori, MO: Triumph Books.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Curtis, W. J., & Cicchetti, D. (2003). Moving research on resilience into the 21st century: Theoretical and methodological considerations in examining the biological contributors to resilience. Development and Psychopathology [Special Issue: Conceptual, methodological, and statistical issues in developmental psychopathology], 15, 773–810.

Deckro, G. R., Ballinger, K. M., Hoyt, M., Wilcher, M., Dusek, J., Myers, P., et al. (2002). The evaluation of a mind/body intervention to reduce psychological distress and perceived stress in college students. Journal of American College Health, 50, 281–287.

Driskill, J. D. (1999). Protestant spiritual exercises: Theology, history, and practice. Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing.

Dunn, B. R., Hartigan, J. A., & Mikulas, W. L. (1999). Concentration and mindfulness meditations: Unique forms of consciousness? Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback, 24, 147–165.

Easwaran, E. (1991). Meditation: A simple eight-point program for translating spiritual ideals into daily life (2nd ed.). Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press. (full text: http://www.easwaran.org) (Original work published 1978)

Easwaran, E. (2003). God makes the rivers to flow: Sacred literature of the world (3rd ed.). Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press. (large parts online: http://www.easwaran.org) (Original work published 1982)

Fetzer (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute (full text: http://www.fetzer.org).

Goleman, D. (1988). The meditative mind: The varieties of meditative experience. New York: Tarcher.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57, 35–43.

Hamilton, N. A., & Ingram, R. E. (2001). Self-focused attention and coping: Attending to the right things. In C. R. Snyder (Ed.) Coping with stress: Effective people and processes (pp. 178–195). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1991). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Dell.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280–287.

Keating, T. (1997). Open mind, open heart. New York: Continuum. (Original work published 1986)

Main, J. (1999). Moment of Christ: The path of meditation. New York: Continuum.

Murray-Swank, N. A., & Pargament, K. I. (2005). God, where are you?: Evaluating a spiritually-integrated intervention for sexual abuse. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 8, 191–203.

Oden, T. C. (1984). Care of souls in the classic tradition. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Oman, D., & Beddoe, A. E. (2005). Health interventions combining meditation with learning from spiritual exemplars: Conceptualization and review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 29, S126.

Oman, D., Flinders, T., & Thoresen, C. E. (in press). Integrating spiritual modeling into education: A college course for stress management and spiritual growth. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion.

Oman, D., Hedberg, J., Downs, D., & Parsons, D. (2003). A transcultural spiritually-based program to enhance caregiving self-efficacy: A pilot study. Complementary Health Practice Review, 8, 201–224.

Oman, D., Hedberg, J., & Thoresen, C. E. (2006). Passage meditation reduces perceived stress in health professionals: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 714–719.

Oman, D., Shapiro, S., Thoresen, C. E., Plante, T. G., & Flinders, T. (in press). Meditation lowers stress and supports forgiveness among college students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American College Health.

Oman, D., & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Spiritual modeling: A key to spiritual and religious growth? The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 13, 149–165.

Oman, D., & Thoresen, C. E. (2006). Applying social cognitive theory to spirituality: Achievements, challenges and prospects. (Paper presented at symposium on Spiritual Transformation: New Frontiers in Scientific Research: Opportunities for Productive Collaboration among the Health and Psychosocial Sciences, Berkeley, CA.).

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York: Guilford.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 519–543.

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37, 710–724.

Park, C. L., & Folkman, S. (1997). Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology, 1, 115–144.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC and New York: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press.

Project MATCH Research Group. (1998). Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 22, 1300–1311.

Ramsay, N. J. (2004). Pastoral care and counseling: Redefining the paradigms. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Seeman, T. E., Dubin, L. F., & Seeman, M. (2003). Religiosity/spirituality and health: A critical review of the evidence for biological pathways. American Psychologist, 58, 53–63.

Shapiro, S. L. (2001). Poetry, mindfulness, and medicine. Family Medicine, 33, 505–6.

Shapiro, S. L., Astin, J. A., Bishop, S. R., & Cordova, M. (2005). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management, 12, 164–176.

Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21, 581–99.

Singer, J. D. (1998). Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 23, 323–355.

Smith, H. (1991). The world's religions: Our great wisdom traditions. San Francisco: Harper San Francisco.

Tarakeshwar, N., Pargament, K. I., & Mahoney, A. (2003). Measures of Hindu pathways: Development and preliminary evidence of reliability and validity. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 316–332.

Thoresen, C. E., Oman, D., & Harris, A. H. S. (2005). The effects of religious practices: A focus on health. In W. R. Miller, & H. D. Delaney (Eds.), Judeo-Christian perspectives on psychology: Human nature, motivation, and change (pp. 205–226). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Tloczynski, J., & Tantriella, M. (1998). A comparison of the effects of Zen breath meditation or relaxation on college adjustment. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient, 41, 32–43.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General system theory: Foundations, development, applications. New York: Braziller.

Wachholtz, A. B., & Pargament, K. I. (2005). Is spirituality a critical ingredient of meditation? Comparing the effects of spiritual meditation, secular meditation, and relaxation on spiritual, psychological, cardiac, and pain outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28, 369–384.

Walsh, R., & Shapiro, S. L. (2006). The meeting of meditative disciplines and western psychology: A mutually enriching dialogue. American Psychologist, 61, 227–239.

Winzelberg, A. J., & Luskin, F. M. (1999). The effect of a meditation program on the level of stress in secondary school student teachers. Stress Medicine, 15,69–77.

Wuthnow, R. (1998). After heaven: Spirituality in America since the 1950s. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support for this work from Metanexus Institute (grant: “Learning from Spiritual Examples: Measures & Intervention”), John Templeton Foundation, Academic Council of Learned Societies, Contemplative Mind in Society, Fetzer Institute, Santa Clara University Internal Grants for Research, and the Spirituality and Health Institute, Santa Clara University. We also thank Sara Tsuboi and Anthony Vigliotta for their invaluable assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Effects of interventions on the 13 outcome variables were analyzed in 13 separate hierarchical linear regression models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Hierarchical linear models (HLMs) are increasingly a tool of choice for analyzing longitudinal data, and are sometimes known, especially among physical scientists, as linear mixed models (Singer, 1998). Compared to more conventional methods such as ANOVA, HLM allows improved handling of unbalanced designs and missing data, and more flexible analyses of data gathered at multiple timepoints. In HLM terminology (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), our regressions used the following model:

In this formula, Y k(i),t represents the outcome for the ith individual within the kth treatment condition (k=1, 2 or 3) at exam t (t=1, 2 or 3). The treatment effect for PM (in this “time-constant” treatment effect model) is represented by β (PM), which is the coefficient of I (PM) k,t , a “Level 1” predictor that is 1 for the PM group at Exams 2 and 3, and 0 otherwise. Thus I (PM) k,t represents whether an individual at time t has received the PM intervention, but the magnitude of benefit (β (PM)) does not vary between timepoints. Similarly, β (MBSR) represents the treatment effect for MBSR, and I (MBSR) k,t is the corresponding indicator. The other terms in the model represent adjustments and an error term. Adjustment for preexisting individual differences in outcome level is included as a “Level 2” random effect, represented by R k(i). Adjustment for group assignment (e.g., baseline group differences, despite their lack of statistical significance) is included as a Level 2 fixed effect, represented by G k . Adjustment for temporal trends that affect all participants equally is included as a Level 1 fixed effect, represented by T t . Residual error, the discrepancy between the observed and expected outcome of individual k(i) at exam t, is represented by the Level 2 random effect ek(i),t, assumed to be independent and normally distributed with mean of zero and a variance of σ2. The global intercept is represented by c 0.

To explore whether the treatment effects might change or decay over time, initial regression models permitted each treatment effect to vary between Exams 2 and 3 (“time-varying” treatment effect model). These time-varying models replaced β (PM) I (PM) k,t in the above formula with β(PM) 2 I (PM,2) k +β (PM) 3 I (PM,3) k where β (PM) t is treatment effect at Exam t, and each I (PM,t) k (for t=2 or 3) is a Level 2 predictor variable equal to 1 at Exam t for PM group participants, and zero otherwise. Similarly, β(MBSR) I (MBSR) k,t was replaced with β (MBSR) 2 I (MBSR,2) k + β (MBSR) 3 I (MBSR,3) k .

We also conducted combined analyses that were based on the assumption of equal effects for the two interventions. These models replaced terms specific to PM (β (PM) I (PM) k,t ) and MBSR (β (MBSR) I (MBSR) k,t ) with generic intervention terms (β (Tx) I (Tx) k,t ).

All regression analyses were implemented using SAS Proc Mixed (Singer, 1998).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oman, D., Shapiro, S.L., Thoresen, C.E. et al. Learning from Spiritual Models and Meditation: A Randomized Evaluation of a College Course. Pastoral Psychol 55, 473–493 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-006-0062-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-006-0062-x