Abstract

This article expands research on adaptive governance in natural resource and climate change policy into other policy areas and the larger context of reform. The purpose is to clarify adaptive governance as a reform strategy, one that builds on experience in a variety of emergent responses to the growing failures of scientific management, the established pattern of governance. Emergent responses in information technology, national security, development aid, and health care policy are reviewed here. In these cases, factoring a large national or international problem into many smaller problems, each more tractable scientifically and politically, opened additional opportunities for advancing common interests on the ground. The opportunities include simplification of research through intensive inquiry, participation in policy decisions by otherwise neglected groups, and selecting what works on the basis of practical experience rather than theory. What works can be improved incrementally in the context at hand, diffused through networks for voluntary adaptation elsewhere, and used to inform higher-level decisions from the bottom up. Adaptive governance is a promising strategy of reform. The open question is whether it will be used well enough to sustain a once-progressive evolution toward fuller realization of human dignity for all.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Merkle (1998, p. 2040). While acknowledging the brilliance of the “lasting technocratic formula” created by the international Scientific Management movement, Merkle (1980, p. 4) also considered it “sometimes difficult to avoid the conclusion that yesterday’s solution may have become today’s problem….” For additional critiques of scientific management, see Havel (1992), Saul (1993), and Scott (1998).

This account is the author’s reconstruction of what happened, which, of course, may differ from the recollections of collaborators directly involved in one series or another.

See Chaps. 2 and 5 in Brunner et al. (2002). Co-authors Elizabeth Olson and Christine Colburn, respectively, took the lead on these two chapters.

See Table 1.1, pp. 33–34, in Brunner et al. (2005). Co-author Lindy Coe-Juell took the lead on the 15-Mile Reach chapter.

For more on the common interest, see Brunner, Colburn et al. (2002, pp. 8–18) and the literature cited therein; Brunner et al. (2005, pp. 9–11, 277–284); and Brunner and Lynch (2010). Compare McDougal et al. (1981, 205): “In the most fundamental sense, international law is a process by which the peoples of the world clarify and implement their common interests in the shaping and sharing of values.” Values are preferred outcomes. An interest is a pattern of value demands supported by the matter-of-fact expectations of an identified person or group.

Lasswell (1971a, pp. 42–43) specified human dignity using the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by General Assembly Resolution 217 A (III) in December 1948. It can be accessed at http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html.

Furthermore, any interest in the community may be discounted if its value demands are inappropriate according to larger community values (e.g., human dignity for all), or if the matter-of-fact expectations supporting the demands as advantageous for a person or group are invalid according to the evidence available. Moreover, conflicting claims about the common interest on a major issue are typically resolved through politics, functionally defined as the giving and withholding of support in making important decisions. (Science-based technology is rarely sufficient for political consensus.)

Because an indefinitely large number of different institutions perform a rather small number of necessary functions, a functional description reduces the risk of being overwhelmed by institutional details. A comprehensive description reduces the risk of misconstruing selected parts for the whole, a common error dramatized in the story of the blind men and the elephant.

The conceptual model distinguishes the values involved, and the significance of the value distinctions became more apparent as field-work on the cases proceeded. The constitutive process is a matter of power, which is based on enlightenment, wealth, well-being, skill, respect, rectitude and affection. The use of power in turn can affect any of these other values. Participants have various value demands (perspectives), and employ various base values (or resources) to shape multiple value outcomes (gains and losses).

As formulated by Lasswell (1971a, p. 16), the postulate “holds that living forms are predisposed to complete acts in ways that are perceived to leave the actor better off than if he had completed them differently. The postulate draws attention to the actor’s own perception of alternative act completions open to him in a given situation.” The perceptions are both conscious and unconscious.

Lasswell et al. (1952; emphasis original) applied the maximization postulate to generate propositions that refer to myth, but the propositions can be generalized to other changes. “The probability of the rejection of a political myth is increased if the adherents experience deprivation rather than indulgence; if attention is directed toward a new myth whose adherents are indulged; and if early adherence to the new myth is followed by relative indulgence” (p. 4). “The line of diffusion is from communities which are most indulged to the ones less indulged. In terms of power, this implies that the strong will be copied by the weak” (p. 5). “The process of diffusion is complicated by the mechanism of ‘partial incorporation,’ which enables an existing pattern of power relations to be preserved at the same time that a foreign myth is largely accepted” (p. 5).

On scaling out and scaling up, see especially the chapters in Brunner et al. (2005) by co-authors Christine Edwards on “Grassbanks: Diffusion and Adaption from the Radical Center,” Lindy Coe-Juell on “The Oregon Plan: A New Way of Doing Business” based on local watershed initiatives, and Christina Cromley on “Community-Based Forestry Goes to Washington.”

Like its predecessor, Box 1.1 should be understood as “a snapshot of two patterns of governance in motion, with the pattern in the first column retreating from areas where it fails to resolve issues that cannot be ignored and the pattern in the second column expanding into some of the ecological niches opened up by the retreat.” From Brunner et al. (2005) on the predecessor, Table 1.1 (pp. 33–34).

For more on scientific management in the climate change regime, see Brunner and Lynch (2010).

See ibid. for more on these exceptions to scientific management.

As Kaplan (1964, p. 43) put it, “Knowing is not one thing that we do among many others, but a quality of any of our doings…. To say that we know is to say that we do rightly in the light of our purposes, and that our purposes are thereby fulfilled is not merely a sign of our knowledge, but its very substance.” This is a major tenet of American pragmatism, in which “inquiry” connotes knowing-in-action. Consider, e.g., Schön (1995, p. 31): “In the domain of practice, we see what John Dewey called inquiry: thought intertwined with action—reflection in and on action—which proceeds from doubt to the resolution of doubt, to the generation of new doubt.”

According to Lasswell et al. (1952, p. 11; emphasis original), “If modern historical and social scientific inquiry has underlined any lesson, it is that the significance of any detail depends upon its linkages to the context of which it is a part. Hence the evaluation of the role of any institutional practice calls for a vast labor of data gathering and theoretical analysis.”

In climate change policy, for example, human choices and decisions are exogenous to predictive models of the “total” Earth System, even though these factors are causes of anthropogenic climate change by definition, and changes in them are necessary to stabilize concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Leadership and political will are recognized as important factors but typically set aside as impractical or impossible to formalize or quantify. For more on this, see Brunner and Lynch (2010).

On those demands, see Friedman (1953, p. 7) which insists that the criteria for theory “are those appropriate for a filing system. Are the categories clearly and precisely defined? Are they exhaustive? Do we know where to file each individual item, or is there considerable ambiguity?”.

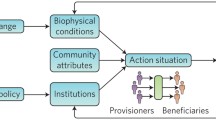

Dietz et al. (2003, pp. 1908–1909) developed their requirements for adaptive governance and summarized them in Fig. 3, p. 210: “Provide necessary information. Deal with conflict. Induce compliance with rules. Provide physical, technical, and institutional infrastructure. Encourage adaptation and change.” Compare these requirements and the eight principles with Box 1.1, and with criteria for ordinary decision process appraisal (Lasswell 1971a, pp. 85–97) and goals for constitutive process (McDougal et al. 1981, pp. 200–222) in the policy sciences.

Unless otherwise noted, the page references that follow in the text are from Leiner et al. (2003), the primary source for this account. Leiner et al. (1997) is an earlier published version of this history. Other sources include Rosenzweig (1998), a review of the literature on the history of the Internet, and more recent updates by Markoff (2009), Ackerman (2009), Crocker (2009), Editors (2009), and Jesdanun (2009).

In packet switching, a message is broken up into a number of small packets of information, each containing the address of the destination. Packets are then transmitted through independent routes and reassembled at the destination. This optimizes available channel capacity, reduces delays, and makes communication more robust: If some computers in the network are down, the message still gets through in packet switching but not in circuit switching.

Leiner et al. (2003, p. 11) credit Tim Berners-Lee as inventor of the Web, an excellent example of unanticipated needs and applications of the Internet. According to Ackerman (2009), “Berners-Lee proposed adding ‘hypertext’ to the Cern network” in March 1989 because he was “stymied by the lack of institutional knowledge” at CERN, the European Laboratory for Particle Physics in the suburbs of Geneva. His first software written in 1990 was posted on the first Web site in 1991, and followed early in 1993 by release of the first graphical browser for the Web by Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina, students at the University of Illinois.

Unless otherwise noted, the page references that follow in the text are from Kilcullen (2009). For more on Kilcullen and his views, see Packer (2006), Kilcullen and Exum (2009), and McGeough (2009). The latter quotes Kilcullen on senior officials in the Bush Administration: “They knew all along that I was against the Iraq war and that I didn't agree with them on Iran. But by the second Bush term they were big enough and probably desperate enough to welcome a different opinion.”.

Kilcullen quotes similar accounts of the syndrome by others: A young Punjabi major in command of a regiment in Pakistan’s paramilitary Frontier Corps in the Federally Administered Tribal Area (p. 34) and an unnamed Afghan provincial governor (p. 39).

But see Sorley (2009), which discerns hard-earned lessons from the latter phases of the war in Vietnam and applies them to Afghanistan. The lessons resemble Kilcullen’s strategy and the surge in Iraq.

In addition to the approaches reviewed in the text below, consider the work of policy scientist Frank Penna in collaboration with others as a consultant to the World Bank in Africa (Penna et al. 2004) and India (Liebl and Roy 2004); for his work in other countries search Penna in worldbank.org. Consider also UN Habitat field worker Samantha Reynolds in Mazar-i-Sharif (Brunner 2004) and others in northern Afghanistan (Tavernise 2009); Dr. Paul Farmer in rural Haiti (Kidder 2004); architect and community planner Hamdi (2004) and his students in Thailand; and mountaineer Greg Mortenson in Pakistan and Afghanistan (Mortenson and Relin 2007). These approaches share a family resemblance with adaptive governance.

Unless otherwise noted, the page references that follow in the text are from Easterly (2006).

Easterly’s critique is oversimplified according to one reviewer (Sen 2006), who nevertheless found in the book the basis for “a reasoned critique of the formulaic thinking and policy triumphalism of some of the economic development literature.”

Emphasis added. “Only” overstates the case. The other realistic ways out of poverty summarized and cited in this section are evidence to the contrary, as contended below.

This refers to Schumacher (1973).

Quoted in Gawande et al. (2009), the primary source for this account. Unless otherwise noted, the page references that follow in the text are from this source. See also Pear (2009) on the political background and immediate influence of Gawande et al. (2009), and Gawande et al. (2009) for an extension of the earlier inquiry.

At the end of his article, Gawande emphasized the central role of doctors in the decision process, and contended that the debate over who provides the insurance (public or private options) is not that critical. However, the central role of doctors does not necessarily mean that other participants—including patients, public and private insurers, vendors of medical products, and legislators—are irrelevant in doctor’s decisions. Indeed, debate within the medical community over health care reform suggests that doctor’s medical decisions are influenced by the government and others.

Clinton as quoted, inter alia, in Bradach (2003, p. 19), a review of literature on scaling up.

Lasswell (1971b, p. 167; emphasis original) anticipated efforts to contract the significance of Vicos; “After all, the objection runs, only two thousand villagers were involved, while the number of peasant hamlets and villages on the face of the earth is in the millions. Part of the reply is this: The program as a whole is transferable with little change to many social and physical environments.” For more on this, see the Conclusion to this article.

In technical terms, Manhattan, Apollo, and the civil rights movement are among the “miranda” (or things to be admired) in the American political myth. On these concepts, see Lasswell and Kaplan (1950, pp. 116–125).

See Brown (1992) and other evidence in Brunner and Lynch (2010) that the substitution of research for action is part of the history of climate change as a policy problem. The political and analytical dynamics are, respectively, defense through partial incorporation and goal substitution (i.e., the substitution of means for ends).

In 2 years, the mandatory school uniform policy significantly reduced violence, theft, and vandalism in the school, with more positive than negative externalities as assessed my most participants and observers. At President Clinton’s direction, the Department of Education distributed a brochure to the nation’s 16,000 school districts providing guidance on adapting the Jackie Robinson Academy’s school uniform policy voluntarily. Many of them did. See Mitchell (1996), Harden (1998), and Sanchez (1998) for more on this precedent.

For more on the Black Hills case, see Brunner et al. (2005, pp. 291–292). See also Chap. 5 by Christine Colburn in Brunner et al. (2002) on the Herger–Feinstein Quincy Library Group Forest Recovery Act of 1998 mandating implementation by the US Forest Service of the QLG’s Community Stability Proposal; and Chap. 6 by Christina Cromley in Brunner et al. (2005) on the modest legislative successes of an organized network of community-based forestry initiatives in the northwest, including the QLG.

For example, Friedman (2009) is concerned about “delegitimation” and the loss of shared identity (the “we”) in American politics; he wonders “whether we can seriously discuss serious issues any longer and make decisions on the basis of the national interest.” Krugman (2009) is concerned that “our political system’s ability to deal with real problems has been degraded to such an extent that I sometimes wonder whether the country is still governable”.

References

Ackerman, E. (2009). 20 years ago, the World Wide Web was born. San Jose Mercury News (March 18).

Adger, W., Neil, S., Dessai, M., Goulden, M., Hulme, I., Lorenzoni, D. R., et al. (2009). Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Climatic Change, 93, 335–354.

Ascher, W. (1978). Forecasting: An appraisal for policy-makers and planners. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Baum, D. (2005). Battle lessons: What the generals don’t know. The New Yorker 80 (January 17), 42–48.

Bradach, J. (2003). Going to scale: The challenge of replicating social programs. Stanford Innovation Review (Spring 2003), 19–25.

Breslin, P. (2004). Thinking outside Newton’s box: metaphors for grassroots development. Grassroots Development, 25(1), 1–9.

Brody, J. E. (2009). A personal, coordinated approach to care. New York Times (June 23), D7.

Brown, G. E. Jr. (1992). Global change and the new definition of progress. Geotimes (June):19–21,

Brunner, R. D. (1994). Myth and American politics. Policy Sciences, 27, 1–18.

Brunner, R. D. (2004). Context-sensitive monitoring & evaluation for the World Bank. Policy Sciences, 37, 103–136.

Brunner, R. D. (2006). A paradigm for practice. Policy Sciences, 39, 135–167.

Brunner, R. D. (2007). The world revolution of our time: A review and update. Policy Sciences, 40, 191–219.

Brunner, R. D., Colburn, C. H., Cromley, C. M., Klein, R. A., & Olson, E. A. (2002). Finding common ground: Governance and natural resources in the American West. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Brunner, R. D., & Lynch, A. H. (2010). Adaptive governance and climate change. Boston: American Meteorological Society.

Brunner, R. D., Steelman, T. A., Coe-Juell, L., Cromley, C. M., Edwards, C. M., & Tucker, D. W. (2005). Adaptive governance: Integrating science, policy, and decision making. New York: Columbia University Press.

Campbell, D. T. (1969). Reforms as experiments. American Psychologist, 24 (April), 409–429.

Campbell, D. T. (1975). ‘Degrees of freedom’ and the case study. Comparative Political Studies, 8(July), 178–193.

Crocker, S. D. (2009). How the Internet got its rules. New York Times (April 7), A29.

Cronbach, L. J. (1975). Beyond the two disciplines of scientific psychology. American Psychologist (February 1975), 116–127.

Dahl, R. A. (1994). The New American political (dis)order. Berkeley, CA: Institute of Governmental Studies, University of California.

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., & Stern, P. C. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons. Science, 302(12 December), 1907–1912.

Doughty, P. L. (2002). Ending Serfdom in Peru: The Struggle for Land and Freedom in Vicos. In D. B. Heath (Ed.), Contemporary cultures and societies of Latin America: A reader in the social anthropology of middle and South America (3rd ed., pp. 225–243). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Douthat, R. (2009). The ghosts of 1994. New York Times (September 14), A21.

Dowd, M. (2009). Boy, oh, boy. New York Times (September 13), Wk17.

Easterly, W. (2006). The white man’s burden: Why the west’s efforts to aid the rest have done so much ill and so little good. New York: Penguin Press.

Editors (2009). Access and the Internet. New York Times (August 29), A20.

Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P., & Nordberg, J. (2005). Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 30, 441–473.

Friedman, M. (1953). Essays in positive economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, T. L. (2009). Where did ‘we’ go? New York Times (September 30), A31.

Gawande, A., Berwick, D., Fisher, E., & McClellan, M. (2009). 10 steps to better health care. New York Times (August 13), A27.

Giridharadas, A. (2009). ‘Athens’ on the Internet. New York Times (September 13), Wk1.

Gould, S. J. (1989). Wonderful life: The burgess shale and the nature of history. New York: W. W. Norton.

Government Accountability Office (GAO 2008). Natural resource management: opportunities exist to enhance federal participation in collaborative efforts to reduce conflict and improve natural resource conditions (GAO-08-262, February), at www.gao.gov.

Gunderson, L., & Light, S. S. (2006). Adaptive management and adaptive governance in the Everglades ecosystem. Policy Sciences, 39, 323–334.

Gwande, A. (2009). The cost conundrum: What a Texas town can teach us about health care. The New Yorker (June 1), 36–44.

Hamdi, N. (2004). Small change: About the art of practice and the limitations of planning in cities. London: Earthscan.

Harden, B. (1998). N.Y. students’ new look; board backs elementary school uniforms. Washington Post (March 19), A1.

Harris, G. (2009a). Hospital shows a way to save: Salaries for doctors, not fees. New York Times (25 July), A21.

Harris, G. (2009b). Role models: Promoting a different way. New York Times (17 September), A21.

Havel, V. (1992). The end of the modern era. New York Times (1 March), E15.

Hayes, S. P. (1959). Conservation and the gospel of efficiency: The progressive conservation movement, 1890–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Herszenhorn, D. M. (2009). Prescriptions: Soaring costs remain a bugaboo in experts’ eyes. New York Times (October 12), A16.

Holmberg, A. R. (1971). The role of power in changing values and institutions of Vicos. In H. F. Dobyns, P. L. Doughty, & H. D. Lasswell (Eds.), Peasants, power, and applied social change: Vicos as a model (pp. 33–63). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Jesdanun, A. (2009). As Internet turns 40, barriers threaten its growth. Associated Press Domestic News Wire (August 30).

Kaplan, A. (1964). The conduct of inquiry. San Francisco, CA: Chandler.

Kidder, T. (2004). Mountains beyond mountains: The quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, a man who would cure the world. New York: Random House.

Kilcullen, D. (2009). The accidental guerilla: Fighting small wars in the midst of a big one. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kilcullen, D., & McDonald Exum, A. (2009). Death from above, outrage down below. New York Times (May 17), wk13.

Krugman, P. (2009). Missing Richard Nixon. New York Times (August 31), A19.

Lasswell, H. D. (1930). Psychopathology and politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lasswell, H. D. (1951). Democratic character. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Lasswell, H. D. (1971a). A pre-view of policy sciences. New York: Elsevier.

Lasswell, H. D. (1971b). The transferability of Vicos strategy. In H. F. Dobyns, P. L. Doughty, & H. D. Lasswell (Eds.), Peasants, power, and applied social change: Vicos as a model (pp. 167–177). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lasswell, H. D. (1971c). The significance of Vicos for the emerging policy sciences. In H. F. Dobyns, P. L. Doughty, & H. D. Lasswell (Eds.), Peasants, power, and applied social change: Vicos as a model (pp. 179–193). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Lasswell, H. D., & Kaplan, A. (1950). Power and society: A framework for political inquiry. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lasswell, H. D., Lerner, D., & Pool, I. de Sola. (1952). The comparative study of symbols: An introduction. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Leiner, B. M., Cerf, V. G., Clark, D. D., Kahn, R. E., Kleinrock, L., Lynch, D. C., et al. (1997). The past and future history of the Internet. Communications of the ACM, 40(2), 102–108.

Leiner, B. M., Cerf, V. G., Clark, D. D., Kahn, R. E., Kleinrock, L., Lynch, D. C., et al. (2003). A brief history of the Internet, version 3.32 (last revised 10 December 2003), which was accessed 21 August 2009 at http://www.isoc.org/internet/history/brief.shtml.

Liebl, M., & Roy, T. (2004). Handmade in India: traditional craft skills in a changing world. In J. M. Finger & P. Schuler (Eds.), Poor people’s knowledge: Promoting intellectual property in developing countries (pp. 95–112). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Markoff, J. (2009). A new Internet? The old one is putting us in jeopardy. New York Times (February 15), WK1.

McDougal, M. S., Lasswell, H. D., & Reisman, W. M. (1981). International law essays. Mineola, NY: Foundation Press.

McGeough, P. (2009). Fighting terror with brain power: Encounter with David Kilcullen. The Age (Melbourne, Australia), (April 18), 8.

Merkle, J. A. (1980). Ideology and management: The legacy of the international scientific management movement. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Merkle, J. A. (1998). Scientific Management. In J. M. Shafritz (Ed.), International encyclopedia of public policy and administration (pp. 2036–2040). Boulder, CO.: Westview Press.

Mitchell, A. (1996). Clinton will advise schools on uniforms. New York Times (February 25), 24.

Mortenson, G., & Relin, D. O. (2007). Three cups of tea: One man’s mission to promote peace…one school at a time. New York: Penguin Books.

Moulitsas, M. (2008). Taking on the system: Rules for radicals in a digital era. New York: Penguin.

Nelson, R., Howden, M., & Smith, M. S. (2008). Using adaptive governance to rethink the way science supports Australian drought policy. Environmental Science & Policy, 11, 588–601.

Obama, B. (2009). President Obama outlines goals for health care reform. Weekly Address (June 6), at http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/WEEKLY-ADDRESS.

Obey, D. (2004). Remarks of Congressman David Obey (D-WI), ranking member of the House Appropriations Committee. The Congressional Record (June 16), p. H4259.

Packer, G. (2006). Knowing the enemy: Can social scientists redefine the “War on Terror”? The New Yorker 80 (December 18):60f.

Pear, R. (2009). Health care spending disparities stir a fight. New York Times (June 9), A17.

Penna, F. J., Thormann, M., & Finger, J. M. (2004). The African music scheme. In J. M. Finger & P. Schuler (Ed.), Poor people’s knowledge: Promoting intellectual property in developing countries (pp. 95–112). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Polak, P. (2008). Out of poverty: What works when traditional approaches fail. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Reddy, S., & Heuty, A. (2008). Global development goals: The folly of technocratic pretensions. Development Policy Review, 26, 5–28.

Rich, F. (2009). Even Glen Beck is right twice a day. New York Times (September 20), Wk8.

Rogers, E. (1995). “Centralized and decentralized diffusion systems” In his Diffusion of Innovations (pp. 364–369). New York: Free Press.

Rosenzweig, R. (1998). Review essay: Wizards, bureaucrats, warriors, and hackers: writing the history of the Internet. American Historical Review (December), 1530–1552.

Sack, K. & Herszenhorn, D. M. (2009). Texas hospital flexing muscle in health fight. New York Times (30 July), A1.

Sanchez, R. (1998). What works: A uniform policy. Washington Post Magazine (September 13), W5.

Saul, J. R. (1993). Voltaire’s Bastards: The dictatorship of reason in the west. New York, NY: Vintage.

Schön, D. A. (1995). Knowing-in-action: The new scholarship requires a new epistemology. Change, 27(November/December), 27–34.

Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is beautiful: Economics as if people mattered. New York: Harper & Row.

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sen, A. (2006). The man without a plan. Foreign Affairs 85 (March/April 2006), 171–177.

Simon, H. A. (1996). The sciences of the artificial (3rd ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sokal, R. R. (1974). Classification: purposes, principles, progress, prospects. Science 185 (27 September), 1115–1123.

Sorley, L. (2009). The Vietnam war we ignore. New York Times (October 18), Wk9.

Stewart, R. (2006). Even in Iraq, all politics is local. New York Times (July 13), A23.

Swarns, R. L. (2009). Outreach in the age of pullback. New York Times (November 12), F1.

Tavernese, S. (2009). Afghan enclave seen as model to rebuild, and rebuff Taliban. New York Times (November 13), A1.

Tripp, C. (2009). All (Muslim) politics is local: How context shapes Islam in power. Foreign Affairs 88 (September/October), 124–129.

Victor, D. G., House, J. C., & Joy, S. (2005). A Madisonian approach to climate policy. Science 309 (16 September), 1820–1821.

Webster, D. G. (2009). Adaptive governance: The dynamics of Atlantic fisheries management. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

Young, K. R., & Lipton, J. K. (2006). Adaptive governance and climate change in the tropical highlands of Western South America. Climatic Change, 78, 63–102.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brunner, R.D. Adaptive governance as a reform strategy. Policy Sci 43, 301–341 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-010-9117-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-010-9117-z