Abstract

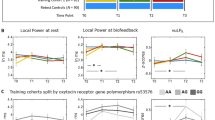

Female undergraduates were assigned to one of three groups, two involving regulatory training and one not. Training participants performed for 2 weeks tasks that required strong behavioral restraint (Strong Training) or weak behavioral restraint (Weak Training). Later, they took part in (1) a laboratory session in which they performed tasks with inhibitory components, and (2) a follow-up week in which they provided health behavior reports and used designated dental supplies. No Training participants took part only in the session and follow-up week. As expected, laboratory performance was improved for Strong- relative to No Training participants, with performance for Weak Training participants falling in between. Also as expected, Strong Training participants used more floss in the follow-up week than did the No Training participants, with floss for Weak Training participants falling between. Contrary to expectation, Strong Training participants used less toothpaste and reported having brushed less than the No Training participants. In addition, Strong Training participants evinced exaggerated—rather than diminished—cardiovascular responses during the laboratory tasks. The performance and floss use data support the suggestion that inhibitory system strength can be increased through use. The brushing and cardiovascular findings may be interpretable in inhibitory strength terms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The computer training programs were written by Aeron Gault, a computer systems analyst in the UAB Psychology department.

We also administered in the laboratory session a modified version of the Insomnia Severity Index (Morin 1993). We did so to evaluate sleep difficulties that participants might have had in the preceding 2 weeks. Analyses showed no differences among groups and no relations between index scores and measures of inhibitory strength. Therefore, this questionnaire will not be discussed further here.

The experimenter took CV samples at 30 s intervals during this rest period, starting at 30 s and ending at 2 min. Values were comparable to those obtained at baseline and did not differ across conditions, Fs < 1.0, ns.

Results for attempts were redundant to those for successes. They indicated the a linear trend (p = .03), with values being greater for Strong- than Weak Training participants, but equivalent for Weak- and No Training participants. Analysis of the success data without the covariate indicated a near-reliable linear trend, F (1, 50) = 3.73, p = .059, and no quadratic effect, F < 1.0.

To guard against measurement (e.g., movement) artifact, we omitted change values that deviated by more than two standard deviations from the mean of their group. The regression of change onto baseline values was non-reliable for all CV measures. Nonetheless, we also examined all change scores with analyses of covariance, including base as the covariate. Findings were virtually identical to those from the ANOVAs.

Additional analyses were performed on the CV change scores excluding scores for the Strong Training participant who had extreme d2 task performance scores. Findings were the same as those obtained with scores for this person included. New Strong Training means for SBP were 17.87 (d2) and 26.10 (cold tolerance). New Strong Training means for DBP were 10.43 (d2) and 17.20 (cold tolerance). New Strong Training means for MAP were 14.64 (d2) and 19.93 (cold tolerance). New Strong Training means for HR were 6.18 (d2) and 12.80 (cold tolerance).

Analysis of the remaining floss data without the covariate yielded a near-reliable linear trend, F (1, 51) = 3.84, p = .056, with no quadratic component, F < 1.0.

Analysis of the brushing report measure without the covariate yielded only a linear trend, F (1, 51) = 6.81, p = .01 (quadratic trend: F < 1.0).

Analysis of the risky behavior measure without the covariate yielded a marginal linear trend, F (1, 51) = 3.07, p = .086, with no quadratic component, F < 1.0.

References

Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 177–181.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego-depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1252–1265.

Baumeister, R. F., Gailliot, M., DeWall, C. N., & Oaten, M. (2006). Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. Journal of Personality, 74, 1773–1801.

Berntson, G. G., Cacioppo, J. T., & Quigley, K. S. (1993). Cardiac psychophysiology and autonomic space in humans: Empirical perspectives and conceptual implications. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 296–322.

Brehm, J. W. (1956). Post-decision changes in the desirability of alternatives. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52, 384–389.

Brickenkamp, R. (1981). Test d2 (7th ed.). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Brinkmann, K., & Gendolla, G. H. (2007). Dysphoria and mobilization of mental effort: Effects on cardiovascular reactivity. Motivation and Emotion, 31, 71–82.

Brinkmann, K., & Gendolla, G. H. (2008). Does depression interfere with effort mobilization? Effects of dysphoria and task difficulty on cardiovascular response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 146–157.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ford, C. E., & Brehm, J. W. (1987). Effort expenditure following failure. In C. R. Snyder & C. E. Ford (Eds.), Coping with negative life events: Clinical and social psychological perspectives (pp. 51–79). New York: Plenum.

Gailliot, M. T., & Baumeister, R. F. (2007). Self-regulation and sexual restraint: Dispositionally and temporarily poor self-regulatory abilities contribute to failures at restraining sexual behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 173–186.

Gailliot, M. T., Baumeister, R. F., Schmeichel, B. J., DeWall, C. N., Maner, J. K., Plant, E. A., et al. (2007). Self-control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: Willpower is more than a metaphor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 325–336.

Gendolla, G. H. E., & Krüsken, J. (2002). The joint effect of informational mood impact and performance-contingent incentive on effort-related cardiovascular response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 271–285.

Jamieson, J. (2004). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with difference scores. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 52, 277–283.

Krupp, L. B., LaRocca, N. G., Muir-Nash, J., & Steinberg, A. D. (1989). The fatigue severity scale: Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Archives of Neurology, 46, 1121–1123.

Langer, E. J., & Abelson, R. P. (1972). The semantics of asking a favor: How to succeed without really dying. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 26–32.

Light, K. C., & Obrist, P. A. (1980). Cardiovascular response to stress: Effects of the opportunity to avoid shock, shock experience, and performance feedback. Psychophysiology, 17, 243–252.

Llabre, M. M., Spitzer, S. B., Saab, P. G., Ironson, G. H., & Schneiderman, N. (1991). The reliability and specificity of delta versus residualized change as measures of cardiovascular reactivity to behavioral challenges. Psychophysiology, 28, 701–711.

Marcora, S. M., Bosio, A., & de Morree, H. M. (2008). Locomotor muscle fatigue increases cardiorespiratory responses and reduces performance during intense cycling exercise independent of metabolic stress. American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 294, 874–883.

Morin, C. M. (1993). Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management. New York, London: Gilford Press.

Muraven, M. B., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and the depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126, 247–259.

Muraven, M. B., Baumeister, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (1999). Longitudinal improvement of self-regulation through practice: Building self-control through repeated exercise. Journal of Social Psychology, 139, 446–457.

Muraven, M. B., Shmueli, D., & Burkley, E. (2006). Conserving self-control strength. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 524–537.

Muraven, M. B., & Slessareva, E. (2003). Mechanisms of self-control failure: Motivation and limited resources. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 894–906.

Muraven, M. B., Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 774–789.

Oaten, M., & Cheng, K. (2006a). Improved self-control: The benefits of a regular program of academic study. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 28, 1–16.

Oaten, M., & Cheng, K. (2006b). Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular physical exercise. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 717–733.

Oaten, M., & Cheng, K. (2007). Improvements in self-control from financial monitoring. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28, 487–501.

Obrist, P. A. (1981). Cardiovascular psychophysiology: A perspective. New York: Plenum Press.

Richter, M., Friedrich, A., & Gendolla, G. H. E. (2008). Task difficulty influences on cardiac reactivity. Psychophysiology, 45, 869–875.

Schmeichel, B. J. (2007). Attention control, memory updating, and emotion regulation temporarily reduce the capacity for executive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136, 241–255.

Schmeichel, B. J., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2003). Intellectual performance and ego depletion: Role of the self in logical reasoning and other information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 33–46.

Simon, L., Greenberg, J., & Brehm, J. W. (1995). Trivialization: The forgotten mode of dissonance reduction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 247–260.

Smith, T. W., Baldwin, M., & Christenson, A. J. (1990). Interpersonal influence as active coping: Effects of task difficulty on cardiovascular reactivity. Psychophysiology, 27, 429–437.

Vohs, K. D., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2003). Self-regulation and the extended now: Controlling the self alters the subjective experience of time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 217–230.

Winer, B. J. (1971). Statistical principles in experimental design (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Wright, R. A. (1996). Brehm’s theory of motivation as a model of effort and cardiovascular response. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 424–453). New York: Guilford.

Wright, R. A. (2008). Refining the prediction of effort: Brehm’s distinction between potential motivation and motivation intensity. Social and Personality Psychology Compass: Motivation and Emotion, 2, 682–701.

Wright, R. A., Junious, T. R., Neal, C., Avello, A., Graham, C., Herrmann, L., et al. (2007). Mental fatigue influence on effort-related cardiovascular response: Difficulty effects and extension across cognitive performance domains. Motivation and Emotion, 31, 219–231.

Wright, R. A., & Kirby, L. D. (2001). Effort determination of cardiovascular response: An integrative analysis with applications in social psychology. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 33, pp. 255–307). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Gregory Fleming James Cystic Fibrosis Research Center. Siu-kuen Azor Hui is now at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hui, Sk.A., Wright, R.A., Stewart, C.C. et al. Performance, cardiovascular, and health behavior effects of an inhibitory strength training intervention. Motiv Emot 33, 419–434 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-009-9146-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-009-9146-0