Abstract

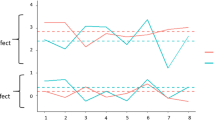

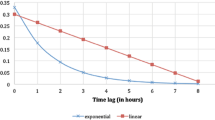

Little is known about the magnitude and duration of mood responses to daily negative events as a function of gender, history of mood disorder, and current substance use. Using computerized ambulatory monitoring techniques, perceived negativity of minor daily events and state affect were prospectively examined every 3 h on average for a 7-day period. Event negativity was associated with depressed mood for 6–9 h following event occurrence, and was associated with happy mood for 3–6 h. Gender and substance use moderated the relationship between event negativity and mood states concurrently, and remained influential for approximately 3 h following the event. History of mood disorder did not moderate any within- or across-day relationships between event negativity and mood. No evidence was found for mood uplifts following daily events in either within- or across-day analyses. The findings are discussed relative to assessment timing in investigations of vulnerability-stress theories.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Affleck, G., Tennen, H., Urrows, S., & Higgins, P. (1994). Person and contextual features of daily stress reactivity: Individual differences in relations of undesirable daily events with mood disturbance and chronic pain intensity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 329–340. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.2.329.

Almeida, D. M. (2005). Resilience and vulnerability to daily stressors assessed via diary methods. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 64–68. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00336.x.

Almeida, D. M., & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Everyday stressors and gender differences in daily distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 670–680. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.670.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 579–616. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030.

Bolger, N., DeLongis, A., Kessler, R. C., & Schilling, E. A. (1989). Effects of daily stress on negative mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 808–818. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.808.

Bolger, N., & Schilling, E. A. (1991). Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality, 59, 355–386. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00253.x.

Bolger, N., & Zuckerman, A. (1995). A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 890–902. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.890.

Brook, J. S., Cohen, P., & Brook, D. W. (1998). Longitudinal study of co-occurring psychiatric disorders and substance use. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 37, 322–331.

Cohen, L. H., Gunthert, A. C., Butler, A. C., O’Neill, S. C., & Tolpin, L. H. (2005). Daily affective reactivity as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality, 73, 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00363.x.

DeLongis, A., Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 486–495. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.486.

First, M., Spitzer, R., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. (1995). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Husky, M. M., Mazure, C. M., Maciejewski, P. K., & Swendsen, J. D. (2007). A daily life comparison of sociotropy-autonomy and hopelessness theories of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 31, 659–676. doi:10.1007/s10608-006-9025-x.

Kendler, K. S., Thornton, L. M., & Gardner, C. O. (2000). Stressful life events and previous episodes in the etiology of major depression in women: An evaluation of the ‘Kindling’ hypothesis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1243–1251. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1243.

Kessler, R. C. (1997). The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 191–214. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191.

Larsen, R. J., & Diener, E. (1992). Promises and problems with the circumplex model of emotion. In M. S. Clark (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology (pp. 25–59). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, D. V., Weiller, E., Amorim, P., Bonora, I., Sheehan, K. H., et al. (1997). The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to the CIDI. European Psychiatry, 12, 224–231. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8.

Maciejewski, P. K., Prigerson, H. G., & Mazure, C. M. (2001). Sex differences in event-related risk for major depression. Psychological Medicine, 31, 593–604.

Marco, C. A., & Suls, J. (1993). Daily stress and the trajectory of mood: Spillover, response assimilation, contrast, and chronic negative affectivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 1053–1063. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.1053.

Mazure, C. M. (1998). Life stressors as risk factors in depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 291–313.

Mohr, C. D., Armeli, S., Ohannessian, C. M., Tennen, H., Carney, A., Affleck, G., et al. (2003). Daily interpersonal experiences and distress: Are women more vulnerable? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 22, 393–423.

Nezlek, J. B., & Allen, M. R. (2006). Social support as a moderator of day-to-day relationships between daily negative events and psychological well-being. European Journal of Personality, 20, 53–68. doi:10.1002/per.566.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2001). Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 173–176. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00142.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Larson, J., & Grayson, C. (1999). Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 1061–1072. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1061.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Morrow, J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1993). Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 20–28. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.102.1.20.

O’Neill, S. C., Cohen, L. H., Tolpin, L. H., & Gunthert, K. C. (2004). Affective reactivity to daily interpersonal stressors as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 172–194. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.2.172.31015.

Patton, G. C., Coffey, C., & Carlin, J. B. (2002). Cannabis use and mental health in younger people: Cohort study. British Medical Journal, 325, 1195–1198. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195.

Paykel, E. S. (2003). Life events and affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108, 61–66. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.13.x.

Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J., Delespaul, P., & de Vries, M. (2003). Effects of daily events on mood states in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 203–211. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.203.

Raudenbush, S., Bryk, A., & Congdon, R. (2005). HLM for Windows, Version 6.03. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International.

Schuckit, M. A. (1986). Genetic and clinical implications of alcoholism and affective disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 143, 140–147.

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavas, J., Weiller, E., et al. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 22–33.

Sloan, D., Strauss, M., & Wisner, K. (2001). Diminished response to pleasant stimuli by depressed women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 488–493. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.3.488.

Solomon, R. L. (1980). The opponent-process theory of acquired motivation: The costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. The American Psychologist, 35, 691–712. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.35.8.691.

Solomon, R. L., & Corbit, J. D. (1974). An opponent-process theory of motivation: I. Temporal dynamics of affect. Psychological Review, 81, 119–145. doi:10.1037/h0036128.

Swendsen, J. D., Tennen, H., Carney, M. A., Affleck, G., Willard, A., & Hromi, A. (2000). Mood and alcohol consumption: An experience sampling test of the self-medication hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(2), 198–204. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.198.

Wilhelm, P., & Schoebi, D. (2007). Assessing mood in daily life: Structural validity, sensitivity to change and reliability of a short-scale to measure three basic dimensions of mood. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 23, 258–267. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.23.4.258.

Williams, K. J., Suls, J., Alliger, G. M., Learner, S. M., & Wan, C. K. (1991). Multiple role juggling and daily mood states in working mothers: An experience sampling study. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 664–674. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.76.5.664.

Wittchen, H. U. (1994). Reliability and validity studies of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28, 57–84. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1.

Zautra, A. J., Guarnaccia, C. A., & Dohrenwend, B. P. (1986). Measuring small life events. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 629–665. doi:10.1007/BF00931340.

Zautra, A. J. (2003). Emotions, stress, and health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, E.I., Husky, M., Grondin, O. et al. Mood trajectories following daily life events. Motiv Emot 32, 251–259 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9106-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9106-0