Abstract

We present a general model of why “thinking a lot” is a key presentation of distress in many cultures and examine how “thinking a lot” plays out in the Cambodian cultural context. We argue that the complaint of “thinking a lot” indicates the presence of a certain causal network of psychopathology that is found across cultures, but that this causal network is localized in profound ways. We show, using a Cambodian example, that examining “thinking a lot” in a cultural context is a key way of investigating the local bio-cultural ontology of psychopathology. Among Cambodian refugees, a typical episode of “thinking a lot” begins with ruminative-type negative cognitions, in particular worry and depressive thoughts. Next these negative cognitions may induce mental symptoms (e.g., poor concentration, forgetfulness, and “zoning out”) and somatic symptoms (e.g., migraine headache, migraine-like blurry vision such as scintillating scotomas, dizziness, palpitations). Subsequently the very fact of “thinking a lot” and the induced symptoms may give rise to multiple catastrophic cognitions. Soon, as distress escalates, in a kind of looping, other negative cognitions such as trauma memories may be triggered. All these processes are highly shaped by the Cambodian socio-cultural context. The article shows that Cambodian trauma survivors have a locally specific illness reality that centers on dynamic episodes of “thinking a lot,” or on what might be called the “thinking a lot” causal network.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, among Cambodian refugees the following has been found: the presence of “thinking a lot” is highly associated with PTSD presence (Hinton et al. 2012a), the severity of “thinking a lot” is highly correlated to PTSD severity (r = .78) (Hinton et al. 2013), and improvement in the severity of “thinking a lot” across treatment is highly correlated to PTSD improvement (r = .70) (Hinton et al. 2012b). Furthermore, a study (Hinton, Reis, and de Jong 2016) among Cambodian refugees showed that the effect of “thinking a lot” on PTSD is mediated to a considerable extent by “thinking a lot”-caused somatic symptoms, by catastrophic cognitions about “thinking a lot”-caused somatic symptoms, and by “thinking a lot”-caused insomnia.

Current research suggests that psychopathology results and is maintained by causal networks of interacting symptoms––not just by some underlying “disorder.” As an example of such network interactions, worry leads to insomnia that leads to exhaustion that leads to impaired ability to cope that leads to more worry, and so forth (Borsboom and Cramer 2013; McNally 2012).

Thus, we will refer to repetitive negative cognizing and “ruminating” in the broad sense that includes repeatedly thinking about any negative topic such as worries, depressive themes, past negative events (e.g., traumas), or anger issues.

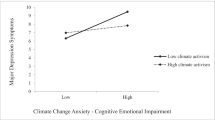

In the DSM it is assumed that there are discrete conditions like generalized anxiety disorder, major depression, or PTSD. In contrast to this, the “thinking a lot” model (Fig. 1) allows for hybrid disorders in which multiple types of psychopathological processes interact and so too do symptoms induced by those processes.

As explained by Barlow et al. (2014), the tendency to such psychopathological tendencies as engaging in dysfunctional worry/rumination has complex origins that include genetics and stress/trauma.

Other aspects of the socio-somatics of “thinking a lot” are how others react to the episodes and the social and economic effects of having the episodes.

Unlike the usual model of psychopathology that focuses on just one kind of cognition such as worry or depressive thoughts, this model (Fig. 1) is much more dynamic, allowing comorbidity, and is transdiagnostic.

In addition, arousal will tend to lead to irritability, anxiety, and depression, which in turn cause poor functioning; and arousal will also worsen any underlying psychopathological dimension or any DSM disorder, for example, major depressive disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder.

That is, the trauma memory is a network characterized by negative mood, mental symptoms, and somatic symptoms, so that experiencing any of these “network nodes”––namely, negative mood, mental symptoms, or somatic symptoms––will activate the memory network and so cause recall of the trauma memory.

We asked about episodes in the last week to assure accuracy of recall.

The various worry topics could be of the same type, for example, two issues of financial concern, or be of different type, for example, one financial and one health concern.

Often patients said that “thinking a lot” made them irritable even though the “thinking a lot” episode did not involve an anger topic, such as when “thinking a lot” about a worry topic brought about irritability. This illustrates another way in which negative cognitions of different types trigger one another, as is shown in Fig. 1.

The word arâm means both attentional object and mood, suggesting that the attentional focus determines mood, a Buddhist idea.

These reduplicative-type expressions highlight that “thinking a lot” is the opposite of the Buddhist ideal of the concentrated one-pointed attention, samathi.

Or a similar expression, “kut tdeupih tdeupeah” (“think tdeupih tdeupeah”).

In a variant of these expressions, some patients configured “thinking a lot” as the “picking up” and cognizing of one object after another, the act of grasping being compared to the attentional spotlight: “Take this thing here and think it, then take that thing there and think it” (youk maok kut nih kut nuh).

For “spinning-and-swirling,” as well as almost all the expressions depicting “thinking a lot” as a dizziness, four forms can be formed, though in this section we just presented #2 in the following four possibilities: (1) “x”; (2) “think x” (kut), (3) “attentional focus x” (arâm), or (4) “mind-mood x” (ceut). So for example, a patient might say any of the following: (1) “spinning-and-swirling” (wul wuel), (2) “think spinning-and-swirling” (kut wul wuel), (3) “attentional focus spinning-and-swirling” (arâm wul wuel), or (4) “mind-mood spinning-and-swirling” (ceut wul wuel).

In some languages the term for “thinking a lot” seems to use reduplicative-type sound symbolism to convey a sense of excessive thought. For example, “thinking a lot” in the Shona language (a Bantu language) is kufungisisa (Patel, Simunyu, and Gwanzura 1995), with kufunga meaning “to think,” kufung-isa “to think much,” and kufung isi sa “to think too much or excessively” (personal communication, Dixon Chabanda); thus, the terminal “isisa” creates a sense of repetition.

These expressions promote metaphor-guided somatization.

The term khwâl suggests water that has just been agitated to muddiness (e.g., owing to falling rain or livestock walking through), and the reduplicative khwâl khwaay suggests spinning through sound symbolic means. This sound symbolism results from the reduplicative structure (repetition of “khw”) and shift (the shift in word ending from “wâl” to “waay”) and through the “w + vowel + l” structure: many words in Cambodian indicating spinning are formed with a “w + vowel” structure, in particular with the “w + vowel + l” structure, some examples being wul and wuel.

Attending to the breath is also a form of mindfulness because there is an attending to something going on in the present moment, namely, breathing.

The object of attention is called “kaseun” in Pali.

Monks used some of these expressions to explain cure, articulating a kind of metaphor word game that is part of the ethnopsychology of cure. As a typical example, some monks said that “thinking a lot” (kut caraeun) put the mind in a state of “agitated turbidity” (khwâl khwaay) and that doing concentration meditation was like adding to water the special chemical (sac cuu) that makes the sediment fall to the bottom of the container; and monks often further explained that doing insight meditation was like taking the sediment out of the container so that any mental upset would not cause mental turbidity.

We did not use one migraine criteria, namely, lasting over 4 h if not treated, because it is difficult for patients to assess how long an untreated headache episode would last since they usually treated the episodes in some way.

The migraine literature indicates that the blurry vision, which is referred to as an aura, usually precedes and heralds a headache (Sacks 1999).

A scotoma was considered to be any positive visual phenomenon distorting or blocking vision such as a scintillating scotoma or phosphenes (Sacks 1999).

As indicated above, visual distortions associated with a migraine headache are often called auras.

A scintillating scotoma has one border that resembles undulating flames, flames that are often multi-colored; and inwards of that flaming border is a dark area of blurriness that is often like a circular base to the flaming edge (see Fig. 4). Often the scintillating scotoma may begin as a small circular shadow area from which a scintillating border soon emerges, slowing expanding.

And these are avoided for fear of inducing a khyâl attack: see Study V.

The percentages are greater than 100 % because some patients mentioned more than one symptom.

The categories overlap to some extent: the mental syndrome of “floating mind” includes fears of spirit attack.

As described below, a khyâl attack, or “wind attack,” is the cultural syndrome by which Cambodian refugees explain most anxiety symptoms. Almost any somatic symptom of anxiety may be attributed to the sudden surge upward in the body of khyâl and blood: khyâl and blood hit the heart, causing palpitations; distend the neck vessels, causing neck soreness; and surge into the cranium, causing dizziness. The khyâl ethnophysiology results in multiple catastrophic cognitions about anxiety symptoms.

Cambodians greatly fear spirits because they may make one ill or even die. For one, the fright caused by spirits is thought to possibly cause death. And secondly, if one follows a beckoning spirit (e.g., in a dream), death may result. Upon dying in either of these two ways, one’s spirit joins the spirit of the dead to be a companion or slave, becoming a spirit in a purgatory state.

Cambodian Buddhism emphasizes attention in several expressions: samathi, or “concentration meditation”; sati, or “mindfulness,” meaning to remember what is occurring in your bodily senses, mind, and surroundings; and smaradeuy, or “memory,” meaning to always remember where one is and what is going on. There is also the term kaseun, which means the object on which attention is placed. All these Cambodian terms have an equivalent term in Pali that is similar in spelling. The patients also used several purely Cambodian terms to express Pali concepts, such as “smeung smaat,” which like samathi means to put the attention on one object.

Ceut might be translated as “mind-mood,” “emotion-cognitive focus,” or “what determines the emotion and cognitive state,” and is here translated as “attentional focus.” The term arâm has a similar meaning, indicating both emotion itself and attentional focus. The terms “ceut” and “arâm” suggest that mood is determined by what is being focused on. These terms illustrate the profound influence of Buddhism on the Cambodian language, and, in fact, the words are of Pali origin.

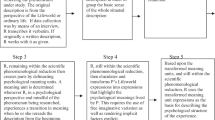

For the survey, as is shown in Fig. 10, we just assessed “flipping the attentional object” and “engaging in activity” to capture this category.

In doing these practices, patients emphasized the importance of not letting the mind wander but rather of “establishing” (tdang), that is, putting, the attentional focus on one object or activity.

Some patients do coining with khyâl oil, which has the same active ingredients but they are added to an oil rather than an ointment.

The term toxique was used in French colonial medicine to describe a severe state of surmenage that led to irritability and rapidly induced palpitations and other somatic symptoms.

More exactly, mental effort is said to lead to cerebral surmenage, or cerebral neurasthenia.

The French used the term “surmenage” interchangeably with “neurasthénie.” In France, spasmophilie became a common diagnosis starting in about 1950, a new guise of neurasthenia. It was treated with calcium, owing to theories hypothesizing that low calcium led to a sort of irritable reactivity (Hinton and Hinton 2009). For this reason, in the colonial and following period, Cambodia patients were often given calcium as treatment for surmenage and related conditions.

As we have tried to emphasize, the embeddedness of “thinking a lot” leads to its being a local ontology of psychopathology but the particular cultural case of “thinking a lot” will share certain features with “thinking a lot” in other cultural contexts owing to a common psychobiology of the involved “repetitive negative cognizing” processes and the resulting causal network (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 is an emic-etic model.

Some of the reported mental and somatic symptoms lasted after the end of the acute episodes. Mental symptoms like forgetfulness and poor concentration were most acute during the episodes but continued into the following time period, as did vegetative symptoms like poor appetite and weakness. It may be that “thinking a lot” creates a baseline state of arousal and dysphoria that affects these biological systems.

We have elsewhere shown that traumatized Cambodian refugees have extreme emotional, mental, and somatic reactivity to upsetting cognitions and to a wide range of stimuli, from sounds to odors (Hinton, Nickerson, and Bryant 2011). The question remains as to whether the “reactivity” results from direct emotional induction or from the activation of trauma associations and catastrophic cognitions by “thinking a lot” and its symptoms.

A previous study with Cambodian refugees showed that blurry vision was related to severity of trauma events, and was common among women who had lost multiple children (Caspi et al. 1998). We would suggest that this blurriness was occurring during “thinking a lot” episodes, such as “thinking a lot” episodes in which the cognition was worry or bereavement in type.

Similarly, other cultural groups interpret trauma symptoms in terms of spirit attack: traumatized African populations sometimes consider their anxiety-type symptoms (e.g., tinnitus) to indicate possession, as do Vietnamese populations (de Jong and Reis 2013; Gustafsson 2009; Igreja et al. 2010; Neuner et al. 2012; Reis 2013). Such spirit interpretation of trauma symptoms leads to a very different socio-cultural course of PTSD.

Both the hallucinations that occur during sleep paralysis and those that occur during waking in the form of visual aura may play a particularly important role in generating fear. One study suggested that sleep paralysis with hallucinations is sufficient in itself to cause PTSD if the hallucinated form is considered to be a malevolent being (McNally et al. 2004). As indicated above, Cambodian refugees not only have extremely high rates of such sleep paralysis hallucinations but also often have scintillating scotoma and other visual phenomena that are considered to be attacking spirits. When attributed to spirit attack both the sleep paralysis hallucinations and visual auras would have a severe “stressor” effect. In both cases there is a sense of unavoidable approach, of attack, leading to a sense of terror and extreme autonomic arousal. In addition, just as sleep paralysis and associated hallucinations may perpetuate local mythologies of supernatural beings so too may visual auras.

Cassaniti and Luhrmann (2014) refer to how cultural frames promote the experiencing of spiritual encounters as “cultural priming.”

One can also trace the colonial influence of the concept of “neurasthenia” on the conceptualization of “thinking a lot” in areas other than Cambodia. In Nigeria, a former colony of Britain, the prominence of “brain fag” was an example of another localization of cerebral neurasthenia. In Nigeria, cerebral neurasthenia, or “brain fag” (a common British term for the disorder), was also said to be due to overstudy and overthinking and was particularly prominent in students (Ola, Morakinyo, and Adewuya 2009; Prince 1960). In the Yoruba context (Yoruba being the major cultural group of Nigeria), coolness is highly emphasized as a value, as in “coolness” of the head, symbolizing physical state and also a calm and balanced character. In the Nigerian context, “thinking” came to be considered a heating of the head and the heated head was configured as the burned-out end of a cigarette, the “fag.” Future studies should investigate to what extent cerebral neurasthenia (brain fag) and local “thinking a lot” idioms interacted, leading to new hybrid ontologies, new ethnopsychologies and methods of treatment. We would hypothesize that the idiom of “thinking a lot” may be particularly prominent in certain contexts because of the legacy of neurasthenia and colonial medicine, and certainly the meaning will be influenced by colonial legacies—a hybrid ontology. Kleinman (1986) describes the localization of neurasthenia in China. We would argue that the localization in China might be further examined by investigating the causal network of “thinking a lot” in China, and investigating whether Western methods of cure were adapted to treat “thinking a lot.”

As was discussed in the Introduction, the transcultural model of “thinking a lot” is in keeping with current ideas about psychopathology: dimensional analysis of psychopathology (dimensions like arousal symptoms and catastrophic cognitions), emphasis on rumination (“repetitive thinking”) in generating distress, network model theory, and transdiagnostic models of psychopathology. The bio-cultural model (Fig. 1) might be called a looping, excessive cognizing model of psychopathology, a “rumination model of psychopathology.” This model hypothesized that there are not just distinct disorders like worry, depression, and PTSD. Rather, particular distress episodes may involve all these types of cognitions. Moreover, these disorders mutually reinforce one another: worry will lead to thoughts of past traumas, which may evoke the memory of past failures like relationships. We call this a dynamic comorbidity model. This model is dynamic in that it emphasizes how types of distress interact in particular episodes.

References

American Psychiatric Association. 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Au, S. 2011 Mixed Medicines: Health and Culture in French Colonial Cambodia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Barlow, D. H., S. Sauer-Zavala, J. R. Carl, J. R. Bullis, and K. Ellard. 2014 The Nature, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Neuroticism: Back to the Future. Clinical Psychological Science 2:344-365.

Borsboom, D., and A. O. Cramer. 2013 Network Analysis: An Integrative Approach to the Structure of Psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 9:91-121.

Casey, B. J., N. Craddock, B. N. Cuthbert, S. E. Hyman, F. S. Lee, and K. J. Ressler. 2013 DSM-5 and RDoC: Progress in Psychiatry Research? Nature Reviews: Neuroscience 14(11):810-814.

Caspi, Y., C. Poole, R. F. Mollica, and M. Frankel. 1998 Relationship of Child Loss to Psychiatric and Functional Impairment in Resettled Cambodian Refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186: 484–491.

Cassaniti, J. L., and T. M. Luhrmann. 2014 The Cultural Kindling of Spiritual Experiences. Current Anthropology 55:S333-S343.

de Jong, J. T., ed. 2002 Trauma, War, and Violence: Public Mental Health in Socio-Cultural Context. New York: Plenum.

de Jong, J. T., and R. Reis. 2013 Collective Trauma Resolution: Dissociation as a Way of Processing Post-War Traumatic Stress in Guinea Bissau. Transcultural Psychiatry 50:644-661.

Drost, J., W. van der Does, A. M. van Hemert, B. W. Penninx, and P. Spinhoven. 2014 Repetitive Negative Thinking as a Transdiagnostic Factor in Depression and Anxiety: A Conceptual Replication. Behaviour, Research, and Therapy 63:177-183.

Ehring, T., and E. R Watkins. 2008 Repetive Negative Thinking as a Transdiagnostic Process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 1:192-205.

Ellard, K. K., C. P. Fairholme, C. L. Boisseau, T. J. Farchione, and D. H. Barlow. 2010 Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders: Protocol Development and Initial Outcome Data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 77:88–101.

Ertas, M., B. Baykan, E. K. Orhan, M. Zarifoglu, N. Karli, S. Saip, A. E. Onal, and A. Siva. 2012 One-Year Prevalence and the Impact of Migraine and Tension-Type Headache in Turkey: A Nationwide Home-Based Study in Adults. Journal of Headache Pain 13:147-57.

Good, B. J. 1977 The Heart of What’s the Matter: The Semantics of Illness in Iran. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 1:25–58.

Gustafsson, Mai Lan. 2009 War and Shadows: The Haunting of Vietnam. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Heim, C., D. J. Newport, S. Heit, Y. P. Graham, M. Wilcox, R. Bonsall, A. H. Miller, and C. B. Nemeroff. 2000 Pituitary-Adrenal and Autonomic Responses to Stress in Women after Sexual and Physical Abuse in Childhood. JAMA 284:592-597.

Hertog, T.N., M. de Jong, A.J. van der Ham, D.E. Hinton, and R. Reis in press. “Thinking a Lot” among the Khwe of South Africa: A Key Idiom of Personal and Interpersonal Distress. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry.

Hinton, D. E., and B. J. Good. 2016 The Culturally Sensitive Assessment of Trauma: Eleven Analytic Perspectives, a Typology of Errors, and the Multiplex Models of Distress Generation. In Culture and PTSD: Trauma in Historical and Global Perspective. D.E. Hinton and B.J. Good, eds. Pp. 50-113. Pennsylvenia: University of Pennsylvenia Press.

Hinton, D. E., A. Hinton, D. Chhean, V. Pich, J. R. Loeum, and M. H. Pollack. 2009a Nightmares among Cambodian Refugees: The Breaching of Concentric Ontological Security. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 33:219–265.

Hinton, D. E., A. L. Hinton, K-T. Eng, and S. Choung. 2012a PTSD and Key Somatic Complaints and Cultural Syndromes among Rural Cambodians: The Results of a Needs Assessment Survey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 29:147-154.

Hinton, D. E., and S. D. Hinton. 2009 Twentieth-Century Theories of Panic in the United States: From Cardiac Vulnerability to Catastrophic Cognitions. In Culture and Panic Disorder. D.E. Hinton and B.J. Good, eds. Pp. 113-134. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Hinton, D. E., S. G. Hofmann, M. H. Pollack, and M. W. Otto. 2009b Mechanisms of Efficacy of CBT for Cambodian Refugees with PTSD: Improvement in Emotion Regulation and Orthostatic Blood Pressure Response. CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics 15:255-63.

Hinton, D. E., M. A. Kredlow, E. Bui, M. H. Pollack, and S. G. Hofmann. 2012b Treatment Change of Somatic Symptoms and Cultural Syndromes among Cambodian Refugees with PTSD. Depression and Anxiety 29:148–155.

Hinton, D. E., M. A. Kredlow, V. Pich, E. Bui, and S. G. Hofmann. 2013 The Relationship of PTSD to Key Somatic Complaints and Cultural Syndromes among Cambodian Refugees Attending a Psychiatric Clinic: The Cambodian Somatic Symptom and Syndrome Inventory (SSI). Transcultural Psychiatry 50:347-70.

Hinton, D. E., A. Nickerson, and R. A. Bryant. 2011 Worry, Worry Attacks, and PTSD among Cambodian Refugees: A Path Analysis Investigation. Social Science and Medicine 72:1817–1825.

Hinton, D. E., V. Pich, D. Chhean, and M. H. Pollack. 2005a “The Ghost Pushes You Down”: Sleep Paralysis-Type Panic Attacks in a Khmer Refugee Population. Transcultural Psychiatry 42:46–78.

Hinton, D. E., V. Pich, D. Chhean, M. H. Pollack, and R. J. McNally. 2005b Sleep Paralysis among Cambodian Refugees: Association with PTSD Diagnosis and Severity. Depression and Anxiety 22:47-51.

Hinton, D. E., R. Reis, and J. T. de Jong. 2016 The “Thinking a Lot” Idiom of Distress and PTSD: An Examination of Their Relationship among Traumatized Cambodian Refugees Using the “Thinking a Lot” Questionnaire. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 29:357-380.

Hinton, D. E., E. Rivera, S. G. Hofmann, D. H. Barlow, and M. W. Otto. 2012c Adapting CBT for Traumatized Refugees and Ethnic Minority Patients: Examples from Culturally Adapted CBT (CA-CBT). Transcultural Psychiatry 49:340–365.

Hinton, D. E., V. So, M. H. Pollack, R. K. Pitman, and S. P. Orr. 2004 The Psychophysiology of Orthostatic Panic in Cambodian Refugees Attending a Psychiatric Clinic. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 26:1–13.

Hobfoll, S., and J. de Jong. 2014 Sociocultural and Ecological Views of Trauma: Replacing Cognitive-Emotional Models of Trauma. In Facilitating Resilience and Recovery Following Trauma. L.A. Zoellner and N.C. Feeney, eds. Pp. 69-90. New York: Guilford.

Hollan, D. 2004 Self Systems, Cultural Idioms of Distress, and the Psycho-Biology Consequences of Childhood Suffering. Transcultural Psychiatry 41:62–79.

Igreja, V., B. Dias-Lambranca, D. A. Hershey, L. Racin, A. Richters, and R. Reis. 2010 The Epidemiology of Spirit Possession in the Aftermath of Mass Political Violence in Mozambique. Social Science and Medicine 71:592-9.

Jenkins, J. H., and M. Valiente. 1994 Bodily Transactions of the Passions: El Calor (the Heat) among Salvadoran Women. In The Body as Existential Ground: Studies in Culture, Self, and Experience. T. Csordas, ed. Pp. 163–182. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Juang, K. D., and C. Y. Yang. 2014 Psychiatric Comorbidity of Chronic Daily Headache: Focus on Traumatic Experiences in Childhood, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Suicidality. Current Pain Headache Reports 18:405.

Kabat-Zinn, J. 2005 Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York, N.Y.: Delta Trade Paperbacks.

Kaiser, B., K. McLean, B. A. Kohrt, A. Hagaman, B. Wagenaar, N. Khoury, and H. Keys. 2014 Reflechi Twòp–Thinking Too Much: Description of a Cultural Syndrome in Haiti’s Central Plateau. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 38:448-472.

Kleinman, A. 1986 Social Origins of Distress and Disease: Depression, Neurasthenia, and Pain in Modern China. New Haven: Yale.

McNally, R. J. 2012 The Ontology of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Natural Kind, Social Construction, or Causal System? Clinical Psychology Science and Practice 19:220-228.

McNally, R. J., N. B. Lasko, S. A. Clancy, M. L. Macklin, R. K. Pitman, and S. P. Orr. 2004 Psychophysiological Responding During Script-Driven Imagery in People Reporting Abduction by Space Aliens. Psychological Science 15:493-497.

Miller, K. E., P. Omidian, A. Rasmussen, A. Yaqubi, and H. Daudzai. 2008 Daily Stressors, War Experiences, and Mental Health in Afghanistan. Transcultural Psychiatry 45:611-638.

Neuhauser, H., and T. Lempert. 2004 Vertigo and Dizziness Related to Migraine: A Diagnostic Challenge. Cephalalgia 24:83-91.

Neuner, F., A. Pfeiffer, E. Schauer-Kaiser, M. Odenwald, T. Elbert, and V. Ertl. 2012 Haunted by Ghosts: Prevalence, Predictors and Outcomes of Spirit Possession Experiences among Former Child Soldiers and War-Affected Civilians in Northern Uganda. Social Science and Medicine 75:548-54.

Nichter, M. 2010 Idioms of Distress Revisited. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 34:401–416.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., B. E. Wisco, and S. Lyubomirsky. 2008 Rethinking Rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science 3:400-424.

Ola, B. A., O. Morakinyo, and A. O. Adewuya. 2009 Brain Fag Syndrome - a Myth or a Reality. African Journal of Psychiatry 12:135-143.

Patel, V., E. Simunyu, and F. Gwanzura. 1995 Kufungisisa (Thinking Too Much): A Shona Idiom for Non-Psychotic Mental Illness. Central African Journal of Medicine 41:209-215.

Pedersen, D., H. Kienzler, and J. Gamarra. 2010 Llaki and Nakary: Idioms of Distress and Suffering among the Highland Quechua in the Peruvian Andes. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 34:279-300.

Prince, R. 1960 The “Brain Fag” Syndrome in Nigerian Students. Journal of Mental Science 106:559-570.

Reis, R. 2013 Children Enacting Idioms of Witchcraft and Spirit Possession in Response to Trauma: Therapeutically Beneficial, and for Whom? Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 50:622-643.

Sacks, O. W. 1999 Migraine. New York: Vintage Books.

Segerstrom, S. C., A. L. Stanton, L. E. Alden, and B. E. Shortridge. 2003 A Multidimensional Structure for Repetitive Thought: What’s on Your Mind, and How, and How Much? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85:909-921.

Segerstrom, S. C., A. L. Stanton, S. M. Flynn, A. R. Roach, J. J. Testa, and J. K. Hardy. 2012 Episodic Repetitive Thought: Dimensions, Correlates, and Consequences. Anxiety Stress Coping 25:3-21.

Smith, J. M., and L. B. Alloy. 2009 A Roadmap to Rumination: A Review of the Definition, Assessment, and Conceptualization of This Multifaceted Construct. Clinical Psychology Review 29:116-28.

Theeler, B. J., R. Mercer, and J. C. Erickson. 2008 Prevalence and Impact of Migraine among US Army Soldiers Deployed in Support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Headache 48:876-882.

Yarris, K. E. 2011 The Pain of “Thinking Too Much”: Dolor De Cerebro and the Embodiment of Social Hardship among Nicaraguan Women. Ethos 39:226–248.

Yarris, K. E. 2014 “Pensando Mucho” (“Thinking Too Much”): Embodied Distress among Grandmothers in Nicaraguan Transnational Families. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 38:473-498.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflict of interest

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was conducted as per in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hinton, D.E., Barlow, D.H., Reis, R. et al. A Transcultural Model of the Centrality of “Thinking a Lot” in Psychopathologies Across the Globe and the Process of Localization: A Cambodian Refugee Example. Cult Med Psychiatry 40, 570–619 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-016-9489-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-016-9489-4