Abstract

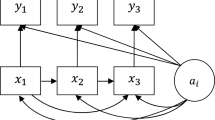

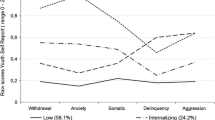

This study revisits a familiar question regarding the relationship between victimization and offending. Using longitudinal data on middle- and high-school students, the study examines competing arguments regarding the relationship between victimization and offending embedded within the “dynamic causal” and “population heterogeneity” perspectives. The analysis begins with models that estimate the longitudinal relationship between victimization and offending without accounting for the influence of time-stable individual heterogeneity. Next, the victimization-offending relationship is reconsidered after the effects of time-stable sources of heterogeneity, and time-varying covariates are controlled. While the initial results without controls for population heterogeneity are in line with much prior research and indicate a positive link between victimization and offending, results from models that control for time-stable individual differences suggest something new: a negative, reciprocal relationship between victimization and offending. These latter results are most consistent with the notion that the oft-reported victimization-offending link is driven by a combination of dynamic causal and population heterogeneity factors. Implications of these findings for theory and future research focusing on the victimization-offending nexus are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

However, it is worth noting that the Schreck et al. (2006) study does control for one particularly prominent source of population heterogeneity, low self-control.

While we primarily focus on these two possibilities, other hypotheses may be relevant as well. Indeed, as we discuss in the conclusion section, there may be a number of interactive possibilities that deserve serious attention in subsequent research.

The response rate in the RSVP is generally consistent with other studies of students that employ active parental consent (see Ellickson and Hawes 1989; Esbensen et al. 1996). Nevertheless, the response rate obtained in the RSVP study calls into question whether the obtained sample is generalizable to the targeted population of adolescents. Past research suggests that active parental consent procedures often produce samples that are biased on racial characteristics (Kearney et al. 1983). However, comparing demographic characteristics from our sample to Kentucky Department of Education enrollment data for the 65 schools in our sample, we find that the racial composition of our sample is fairly close to the KDE population data. In Year 1 our sample percentage nonwhite is 9.55%, while the corresponding figure from the KDE data (which includes all kids in the selected schools, not just 7th graders) is 10.18%. In contrast, our sample does appear to under-represent males, with about 45.5% of the Year 1 respondents being male, compared to 51.9% for the KDE data. Given known gender patterning of delinquent behavior and victimization, we suspect that non-response may understate the prevalence and overall variability of victimization, delinquent behavior and perhaps other “anti-social” factors. Without explicit data on the non-responders, however, we cannot know with any certainty the extent to which they differ from responders.

For the specific variables used in our analysis, the proportion of cases with missing data ranges between 8 and 25.6%. But, when item non-response is considered across all variables simultaneously, it is the case that about 49% of the individuals in the sample have missing values on at least one variable for at least one of the measurement occasions. Consequently, the use of the listwise deletion method for missing data would result in a serious data loss. On the other hand, FIML uses all available information from complete cases as well as the cases with missing data on some (but not all) variables to derive parameter estimates. The inclusion of the information from the partially complete cases contributes to knowledge of the underlying marginal distribution of variables with missing data and thereby can reduce the bias introduced by listwise deletion of cases with missing data, while also improving the efficiency of the estimates. Greater detail on the computation of FIML as well as the advantages and limitations of FIML relative to other missing data procedures are discussed in Allison (2002), Arbuckle (1996), Wothke (2000) and Enders and Bandalos (2001).

Using Mplus, we computed two exploratory factor analyses on these items. In the first analysis, we treat the items as continuous variables. In the second, the items were specified as ordinal variables. Results from both analyses are similar and indicate that the items load on a single factor (e.g., in the latter specification, loadings range between .55 and .98 on a first factor with an eigenvalue of 4.1).

An exploratory factor analyses with these items specified as ordinal categorical indicators indicates that all items load highly on a single factor (loadings range: .72–.96; eigenvalue = 9.6).

In supplemental analyses available from the first author, we utilized “variety” indices that tap the number of different types of crime (rather than a sum of scores across the types) for both the offending and victimization variables. Results from those analyses are substantively identical to those reported below.

Zumbo et al. (2007) find that the traditional computation of alpha yields a negatively biased estimate of reliability when it is applied to ordinal (or binary) items. In contrast, an “ordinal” alpha reliability coefficient derived from a polychoric (or tetrachoric, for binary data) correlation matrix is found to be more accurate. For the multi-item indices utilized in our analysis, we report both the traditional Cronbach’s alpha as well as the ordinal alpha recommended by Zumbo et al.

The survey items and descriptive statistics for all the measures employed in the analyses are presented in “Appendix A”.

An additional benefit of using the structural equation modeling approach is that many SEM software packages (including Mplus, which we utilize) include the “full-information” maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation methods which, as noted, effectively include (rather than exclude) cases with missing data on some analysis variables. These FIML methods have long been known to produce unbiased parameter estimates under the assumption that data are missing at random (MAR). In contrast, listwise deletion of missing data yields unbiased estimates only under the much stronger assumption that data are missing completely at random (MCAR). Consequently, the FIML approach is widely regarded as a superior approach to handling missing data than more traditional approaches such as listwise deletion (e.g., see Enders and Bandalos 2001; Wothke 2000). Another approach to handling missing that has nearly as good statistical properties as FIML is multiple imputation (see Rubin 1987; Allison 2002). As a supplement to our use of FIML estimation, we also utilized the missing data imputation procedures available in Stata version 11 to create 5 imputed datasets. We then re-estimated the full models reported in Table 3 using each of these imputed datasets. As expected, the average parameter estimates from those supplemental analyses yield findings that are numerically very close, and substantively identical, to those reported in Table 3.

All reported results reflect maximum likelihood parameter estimates with robust standard errors that are adjusted for non-normality and the clustering of individuals within schools.

Standard chi-square difference tests are not appropriate when applied to model fit chi-square statistics obtained from maximum likelihood estimators that are robust to non-normality and clustering. Therefore, we utilize the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test, which was developed to address this concern. Detail on this test can be found in Satorra (2000) and useful advice on its practical application can be found on the MPlus website at: http://www.statmodel.com/chidiff.shtml.

References

Agnew R (2001) Building on the foundation of general strain theory: specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. J Res Crime Delinq 38:319–361

Agnew R (2002) Experienced, vicarious, and anticipated strain: an exploratory study on physical victimization and delinquency. Justice Q 19:603–632

Agnew R, Brezina T, Wright JP, Cullen FT (2002) Strain, personality traits, and delinquency: extending general strain theory. Criminology 40:43–72

Allison PD (2000) Inferring causal order from panel data. Paper prepared for presentation at the ninth international conference on panel data, 22 June, Geneva, Switzerland

Allison PD (2002) Missing data. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Allison PD (2005) Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. SAS Institute, Inc, Cary

Anderson E (1999) Code of the streets: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. W.W. Norton & Company, New York

Arbuckle JL (1996) Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE (eds) Advanced structural equation modeling. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Mahwah, pp 243–277

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58:277–297

Bankston WB, Thompson CY, Jenkins QAL, Forsyth CJ (1990) The influence of fear of crime, gender and southern culture on carrying firearms for protection: a causal model. Sociol Q 31:287–305

Baron SW (2004) General strain, street youth and crime: a test of Agnew’s revised theory. Criminology 42:457–483

Baron SW, Hartnagel TF (1998) Street youth and criminal violence. J Res Crime Delinq 35:166–192

Baron SW, Forde DR, Kennedy LW (2001) Rough justice: street youth and violence. J Interpers Violence 16:662–678

Black D (1983) Crime as social control. Am Soc Rev 48:34–45

Brame R, Bushway SD, Paternoster R (1999) On the use of panel research designs and random effects models to investigate state and dynamic theories of criminal offending. Criminology 37:599–641

Broidy LM, Daday JK, Crandall CS, Sklar DP, Jost PF (2006) Exploring the demographic, structural, and behavioral overlap among homicide offenders and victims. Homicide Stud 10:155–180

Burrow JD, Apel R (2008) Youth behavior, school structure, and student risk of victimization. Justice Q 25:349–380

Campbell Augustine M, Wilcox P, Ousey GC, Clayton RR (2002) Opportunity theory and adolescent school-based victimization. Violence Vict 17:233–253

Cao L, Cullen FT, Link BG (1997) The social determinants of gun ownership: self-protection in an urban environment. Criminology 35:629–658

Chesney-Lind M (1997) The female offender: girls, women and crime. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Cook PJ (1986) The demand and supply of criminal opportunities. Crime Justice Annu Rev Res 7:1–28

Cullen FT, Unnever JD, Hartman JL, Turner MG, Agnew R (2008) Gender, bullying victimization, and juvenile delinquency: a test of general strain theory. Vict Offenders 3:346–364

Daigle LE, Cullen FT, Wright JP (2007) Gender difference in the predictors of juvenile delinquency: assessing the generality/specificity debate. Youth Violence Juv Justice 5:254–286

Daigle LE, Beaver KM, Hartman JL (2008) A life-course approach to the study of victimization and offending behaviors. Vict Offenders 3:365–390

Decker SH, Curry GD (2000) Addressing key features of gang membership: measuring the involvement of young members. J Crim Justice 28:473–482

Eitle D, Turner RJ (2002) Exposure to community violence and young adult crime: the effects of witnessing violence, traumatic victimization, and other stressful life events. J Res Crime Delinq 39:124–237

Ellickson PL, Hawes J (1989) An assessment of active versus passive methods for obtaining parental consent. Eval Rev 13:45–55

Enders CK, Bandalos DL (2001) The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Modeling 8:430–457

Esbensen F-A, Deschenes EP, Vogel RE, West J, Arboit K, Harris L (1996) Active parental consent in school-based research: an examination of ethical and methodological considerations. Evaluation Review 20:737–753

Fagan J, Piper ES, Cheng Y-T (1987) Contributions of victimization to delinquency in inner cities. J Crim Law Criminol 78:586–613

Felson RB, Tedeschi JT (eds) (1993) Aggression and violence: social interactionist perspectives. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC

Ferraro KF (1995) Fear of crime: interpreting victimization risk. SUNY Press, Albany

Finkel SE (1995) Causal analysis with panel data. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Fisher BS, Sloan JL, Cullen FT, Chunmeng L (1998) Crime in the ivory tower: the level and sources of student victimization. Criminology 26:671–710

Forde DR, Kennedy LW (1997) Risky lifestyles, routine activities, and the general theory of crime. Justice Q 14:265–294

Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Hay C, Evans MM (2006) Violent victimization and involvement in delinquency: examining predictions from general strain theory. J Crim Justice 34:261–274

Hindelang MJ, Gottfredson MR, Garofalo J (1978) Victims of personal crime: an empirical foundation for a theory of personal victimization. Ballinger, Cambridge

Hsiao C (2003) Analysis of panel data, 2nd edn. University of Cambridge Press, Cambridge

Jacques S, Wright R (2008) The victimization-termination link. Criminology 46:1009–1038

Jensen GF, Brownfield D (1986) Gender, lifestyles, and victimization: beyond routine activity. Violence Vict 1:85–99

Kearney KA, Hopkins RH, Mauss AL, Weisheit RA (1983) Sample bias resulting from a requirement for written parental consent. Public Opin Q 47:96–102

Kubrin CE, Weitzer R (2003) Retaliatory homicide: concentrated disadvantage and neighborhood culture. Soc Probl 50:157–180

Lasley JR (1989) Drinking routines/lifestyles and predatory victimization: a causal analysis. Justice Q 6:529–542

Lauritsen JL, Davis Quinet KF (1995) Repeat victimization among adolescents and young adults. J Quant Criminol 11:143–166

Lauritsen JL, Laub JH (2007) Understanding the link between victimization and offending: new reflections on an old idea. Crime Prev Stud 22:55–75

Lauritsen JL, Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1991) The link between offending and victimization among adolescents. Criminology 29:265–292

Lauritsen JL, Laub JH, Sampson RJ (1992) Conventional and delinquent activities: implications for the prevention of violent victimization among adolescents. Violence Vict 7:91–108

Luckenbill DF (1977) Criminal homicide as situated transaction. Soc Probl 25:176–186

Menard S, Huizinga D (2001) Repeat victimization in a high-risk neighborhood sample of adolescents. Youth Soc 32:447–472

Miller J (1998) Up it up: gender and the accomplishment of street robbery. Criminology 36:37–66

Moriarty LJ, Parsons-Pollard N (2008) Role reversals in the life-course: a systematic review. Vict Offenders 3:331–345

Mundlak Y (1978) On the pooling of time series and cross sectional data. Econometrica 56:69–86

Mustaine EE, Tewksbury R (1998a) Specifying the role of alcohol in predatory victimization. Deviant Behav 19:173–200

Mustaine EE, Tewksbury R (1998b) Predicting risks of larceny theft victimization: a routine activity analysis using refined lifestyle measures. Criminology 36:829–857

Muthén B (1994) Multilevel covariance structure analysis. Sociol Methods Res 22:376–398

Ousey GC, Wilcox P (2007) The interaction of antisocial propensity and life-course varying predictors of delinquent behavior: differences by method of estimation and implications for theory. Criminology 45:313–354

Ousey GC, Wilcox P, Brummel S (2008) Déjà vu all over again: investigating temporal continuity of adolescent victimization. J Quant Criminol 24:307–335

Peterson D, Taylor TJ, Esbensen F-A (2004) Gang membership and violent victimization. Justice Q 21:793–815

Piquero AR, MacDonald J, Dobrin A, Daigle LF, Cullen FT (2005) Self control, violent offending, and homicide victimization: assessing the general theory of crime. J Quant Criminol 21:55–71

Sampson RJ, Lauritsen JL (1990) Deviant lifestyles, proximity to crime and the offender-victim link in personal violence. J Res Crime Delinq 27:110–139

Satorra A (2000) Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans RDH, Pollock DSG, Satorra A (eds) Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis. A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker. Kluwer, London, pp 233–247

Schreck CJ (1999) Criminal victimization and low self-control: an extension and test of a general theory of crime. Justice Q 16:633–654

Schreck CJ, Mitchell Miller J, Gibson CL (2003) Trouble in the school yard: a study of the risk factors of victimization at school. Crime Delinq 49:460–484

Schreck CJ, Stewart EA, Fisher BS (2006) Self-control, victimization, and their influence on risky lifestyles: a longitudinal analysis using panel data. J Quant Criminol 22:319–340

Siegel JA, Williams LM (2003) The relationship between child sexual abuse and female delinquency and crime: a prospective study. J Res Crime Delinq 40:71–94

Singer SI (1986) Victims of serious violence and their criminal behavior: subcultural theory and beyond. Violence Vict 1:61–70

Skogan WG, Maxfield MG (1981) Coping with crime: individual and neighborhood reactions. Sage, Beverly Hills

Spano R, Freilich JD, Bolland J (2008) Gang membership, gun carrying, and employment: applying routine activities theory to explain violent victimization among inner-city, minority youth living in extreme poverty. Justice Q 25:381–410

Sparks RF (1982) Research on victims of crime. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Stewart EA, Schreck CJ, Simons RL (2006) I ain’t gonna let no one disrespect me: does the code of the street reduce or increase violent victimization among African American adolescents? J Res Crime Delinq 43:427–458

Teague R, Mazerolle P, Legosz M, Sanderson J (2008) Linking childhood abuse and adult offending: examining mediating factors and gendered relationships. Justice Q 25:313–348

Von Hentig H (1948) The criminal and his victim: studies in the sociobiology of crime. Schocken Books, New York

Widom CS (1989) Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychol Bull 106:3–28

Wilcox Rountree P, Land KC (1996) Burglary victimization, perceptions of crime risk, and routine activities: a multilevel analysis across Seattle neighborhoods and census tracts. J Res Crime Delinq 33:146–180

Wilcox P, May DC, Roberts SD (2006) Student weapon possession and the “fear and victimization hypothesis”: unraveling the temporal order. Justice Q 23:502–529

Windle M (1994) Substance use, risky behaviors, and victimization among a US national adolescent sample. Addiction 89:175–182

Wolfgang ME (1958) Patterns in criminal homicide. Wiley, New York

Wooldridge JM (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press, Cambridge

Wothke W (2000) Longitudinal and multi-group modeling with missing data. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J (eds) Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: practical issues, applied approaches and specific examples. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah

Wright RT, Decker SH (1997) Armed robbers in action: stickups and street culture. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Wright BRE, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA (2001) The effects of social ties on crime vary by criminal propensity: a life-course model of interdependence. Criminology 39:321–352

Zumbo BD, Gadermann AM, Zeisser C (2007) Ordinal versions of coefficients alpha and theta for Likert rating scales. J Appl Stat Methods 6:21–29

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored, in part, by grant DA-11317 (Richard R. Clayton, PI) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors would like to thank Richard R. Clayton, Scott A. Hunt, Kimberly Reeder, Michelle Campbell Augustine, Shayne Jones, Staci Roberts, and Jon Paul Bryan for their contributions to the Rural Substance abuse and Violence Project, which provides the data analyzed here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ousey, G.C., Wilcox, P. & Fisher, B.S. Something Old, Something New: Revisiting Competing Hypotheses of the Victimization-Offending Relationship Among Adolescents. J Quant Criminol 27, 53–84 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-010-9099-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-010-9099-1