Abstract

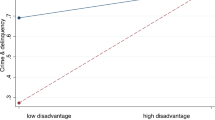

The traditional trait-based approach to the study of crime has been challenged for its failure to acknowledge differences in the social environments to which individuals are exposed. Similarly, community-level explanations of crime have been criticized for failing to take into account important individual differences between criminals and non-criminals. Ultimately, a full understanding of crime requires the consideration of both individual and environmental differences, perhaps most importantly because they may interact to produce offending behavior. Yet little criminological research has examined if the effects of individual-level characteristics vary by the context in which they are embedded. The current study addresses this gap in the literature by using multivariate, multilevel item response models to examine if the influence of impulsivity on offending differs as a function of neighborhood context. Analyses using data from the Project of Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods reveals that the effects of impulsivity are amplified in neighborhoods with higher levels of socioeconomic status and collective efficacy, and lower levels of criminogenic behavior settings and moral/legal cynicism. Implications of these findings for research and policy are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Studies focusing on victimization have also found significant interactions between individual- and community-level characteristics. For example, Miethe and McDowall (1993) found that key routine activities variables have a significant effect on burglary in more affluent areas, but little effect in socially disorganized communities; Rountree et al. (1994) found evidence that individual-level crime opportunity variables interact with neighborhood context to influence violent victimization and burglary; and Velez (2001) found that public social control has a stronger effect on household/personal victimization in more disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Response rates for wave one were 74.3 and 71.6% for the 12- and 15-year-old cohorts, respectively. At wave two, response rates were 86.2 and 82.7%, respectively. Analysis of attrition revealed that participants dropping out of the study were not significantly different than those remaining in the study. In addition, missing data consisted only of 43 participants without valid impulsivity data, representing 3.5% of the sample. Since impulsivity is the key variable in this study, missing impulsivity data was not imputed to protect the validity of the results. However, multiple imputation techniques in Stata (the ICE command) were used to examine potential bias resulting from missing impulsivity data (Royston 2005). Results were not significantly altered using these techniques.

The ten items composing this scale are from the Achenbach Child-Behavior Checklist (CBCL; see Achenbach 1993). Although the scales in the CBCL are normed by sex, the CBCL does not have a preformed index of impulsivity. Therefore, the ten individual items composing the scale were standardized and summed by the researcher.

Previous research has shown that perseverance is not as strongly related to offending as other types of impulsivity (i.e., lack of premeditation, urgency, and sensation seeking) (see Lynam and Miller 2004, for a review of different types of impulsivity; also see Whiteside et al. 2005). Further, the impulsivity index used in this study may tap into a related psychological construct: hyperactivity. These limitations, discussed in detail below, may have numerous implications: lower correlations between impulsivity and offending than in previous studies; results qualitatively and quantitatively different than other studies; and less variability in impulsivity scores in certain neighborhoods.

I wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out the lack of face validity of certain items in the scale.

The second extracted component consisted of the remaining seven items and explained 44% of the variance in the items (eigenvalue = 1.82). The correlation between the two components was 0.61.

Seven of the ten items used to construct the scale were repeated at wave two. The discussion that follows pertains to analysis of these items at waves one and two.

Sensitivity analyses confirmed the neighborhood classification scheme for all of the neighborhood variables. The results did not vary when neighborhood variables were trichotomized by 1/3 splits or 10-80-10 splits. Further, the results were consistent when the neighborhood variables were continuous. For example, the effect of impulsivity (.039) on offending was amplified by .050 units for every standard deviation increase of SES (p < .01). The variables were ultimately trichotomized for ease of interpretability. .

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to confirm that the findings were not due to the operationalization of the dependent variable or the model used. In one model, the violent and property crime items were combined additively (α = .62 and α = .50, respectively); these scales were highly correlated (r = 0.50). Two-level hierarchical linear models were estimated with these scales as dependent variables. In a second model, individuals were coded with a one if they responded affirmatively to any one of the violent and property crime items, respectively, and zero otherwise, and two-level multilevel logistic models were estimated. The results of these models were consistent with those presented below.

Two major assumptions of the model are: (1) additivity: item severities and person propensities contribute additively to the log-odds of a positive item response; and (2) local independence: conditional on item severity and person propensity, item responses are independent Bernoulli random variables. These assumptions imply unidimensionality; that is, each set of item responses taps a single interval-scale construct, in this case, “the propensity to commit (violent and property) crime” (Raudenbush et al. 2003, pp. 177). In addition, the model provides (1) an ordering of the items, in terms of act severity, and (2) a score for each individual on the latent trait; these scores lie on the same scale and can be compared across individuals.

For illustrative purposes, the violent and property crime scales are constructed here as additive indices. As indicated above, the items actually serve as level-one variables in the multilevel item response model.

Given the relatively weak correlation between impulsivity and crime, stronger individual-level correlates of crime were considered. These include peer influence and self-control. The correlations between these factors and offending were generally consistent with those found in previous research (e.g., Pratt and Cullen 2000; Warr 2002).

Between-person reliabilities are 0.65 and 0.54, for the violent and property crime models, respectively. The between-neighborhood reliabilities are 0.32 and 0.08. Not surprisingly, the between-neighborhood reliability for property crime is close to zero (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002, pp. 46–66).

Although it seems to be an anomaly that violent crime is more pervasive than property crime, the two most prevalent offenses in the sample are hitting someone and throwing objects, relatively minor incidents representing violent crime.

An alternative approach would be to first test the significance of a random slope variance on impulsivity, and subsequently think of neighborhood-level variables that could explain the random slope. However, basing the cross-level interactions on a priori substantive arguments is preferable. The power of the statistical tests of the cross-level interaction fixed effects is considerably higher than the power of tests based on the random slopes. In addition, one can test these interactions irrespective of whether a random slope on impulsivity is found (see Snijders and Bosker 1999, pp. 74–75, 95–96).

References

Achenbach TM (1993) The young adult self-report-revised and the young adult behavior checklist. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, Burlington, VT

Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA

Anderson E (1997) Violence and the inner-city street code. In: McCord J (ed) Violence and children in the inner city. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–30

Anderson E (1999) Code of the streets: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. W. W. Norton and Company, New York, NY

Brener ND, Simon TR, Krug EG, Lowry R (1999) Recent trends in violence-related behaviors among high school students in the United States. JAMA 281:440–446

Bursik RJ, Grasmick HG (1993) Neighborhoods and crime: the dimensions of effective community control. Lexington Books, New York, NY

Cadoret RJ, Yates WR, Troughton E, Woodworth G, Stewart MA (1995) Genetic-environmental interaction in the genesis of aggressivity and conduct disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:916–924

Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, Taylor A, Poulton R (2002) Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science 297:851–854

Christiansen KO (1977) A preliminary study of criminality among twins. In: Mednick SA, Christiansen KO (eds) Biosocial bases of criminal behaviour. Gardner Press, New York, NY, pp 89–108

Cleveland HH (2003) Disadvantaged neighborhoods and adolescent aggression: behavioral genetic evidence of contextual effects. J Res Adolesc 13:211–238

Cohen LE, Felson M (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. Am Sociol Rev 44:588–608

Daday JK, Broidy LM, Crandall CS, Sklar DP (2005) Individual, neighborhood, and situational factors associated with violent victimization and offending. Crim Justice Stud 18:215–235

De Boeck P, Wilson M (2004) Exploratory item response models: a generalized linear and nonlinear approach. Springer, New York, NY

Elliott DS, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D, Sampson RJ, Elliott A, Rankin B (1996) The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. J Res Crime Delinq 33:389–426

Ellis L, Walsh A (1999) Criminologists’ opinions about the causes and theories of crime and delinquency. Criminol 24:1–4

Eysenck HJ (1977) Crime and personality. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

Farrington DP (1993) Have any individual, family, or neighborhood influences on offending been demonstrated conclusively? In: Farrington DP, Sampson RJ, Wikstrom P-OH (eds) Integrating individual and ecological aspects of crime (BRA Report). Allmanna Forlaget, Stockholm, pp 7–37

Farrington DP (1994) Psychological explanations of crime. Dartmouth, Brookfield, VT

Farrington DP (1995a) The development of offending and antisocial behavior from childhood: key findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 36:929–964

Farrington DP (1995b) Key issues in the integration of motivational and opportunity reducing crime prevention strategies. In: Wikstrom P-O, Clarke RV, McCord J (eds) Integrating crime prevention strategies: propensity and opportunity. National Council for Crime Prevention, Sweden, pp 333–357

Farrington DP (1998) Individual differences and offending. In: Tonry M (ed) The handbook of crime and punishment. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp 241–268

Furstenberg FF (1993) How families manage risk and opportunity in dangerous neighborhoods. In: Wilson WJ (ed) Sociology and the public agenda. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp 231–258

Gibson CL, Sullivan CJ, Jones S, Piquero AR (2010) “Does it take a village?” Assessing neighborhood influences on children’s self-control. J Res Crime Delinq 47:31–62

Glueck S, Glueck E (1950) Unraveling juvenile delinquency. Commonwealth Fund, New York, NY

Gottfredson M, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Gottfredson DC, McNeil RJ, Gottfredson GD (1991) Social area influences on delinquency: a multilevel analysis. J Res Crime Delinq 28:197–226

Harris KM, Duncan GJ, Boisjoly J (2002) Evaluating the role of “nothing to lose” attitudes on risky behavior in adolescence. Soc Forces 80:1005–1039

Henggeler SW, Borduin CM (1990) Family therapy and beyond: a multisystemic approach to treating the behavior problems of children and adolescents. Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove, CA

Hirschi T (1969) Causes of delinquency. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR (1993) Commentary: testing the general theory of crime. J Res Crime Delinq 30:47–54

Horney J (2006) An alternative psychology of criminal behavior: the American Society of Criminology 2005 Presidential Address. Criminology 44:1–16

Hox JJ (1995) Applied multi-level analysis, 2nd edn. T. T. Publications, Amsterdam

Jaccard JJ, Turrisi R (1990) Interaction effects in multiple regression. Sage, Newbury Park, CA

Jones S, Lynam DR (2009) In the eye of the impulsive beholder: the interaction between impulsivity and perceived informal social control on offending. Crim Justice Behav 36:307–321

Kornhauser RR (1978) Social sources of delinquency. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Kreft IGG, de Leeuw J (1998) Introducing multi-level modeling. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Kubrin CE, Weitzer R (2003) New directions in social disorganization theory. J Res Crime Delinq 40:374–402

Kupersmidt JB, Griesler PC, DeRosier ME, Patterson CJ, Davis PW (1995) Childhood aggression and peer relations in the context of family and neighborhood factors. Child Dev 66:360–375

Lewis O (1961) The children of Sanchez: autobiography of a Mexican family. Random House, New York, NY

Lindstrom P (1995) School context and delinquency. Project metropolitan. Research report no. 41. Department of Sociology, University of Stockholm

Longshore D (1998) Self-control and criminal opportunity: a prospective test of the general theory of crime. Soc Probl 45:102–113

Longshore D, Turner S (1998) Self-control and criminal opportunity. A cross-sectional test of the general theory of crime. Crim Justice Behav 25:81–98

Lynam DR (1996) The early identification of chronic offenders: who is the fledgling psychopath? Psychol Bull 120:209–234

Lynam DR, Miller JD (2004) Personality pathways to impulsive behavior and their relations to deviance: results from three samples. J Quant Criminol 20:319–341

Lynam DR, Wikstrom P-OH, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Loeber R, Novak S (2000) The interaction between impulsivity and neighborhood context on offending: the effects of impulsivity are stronger in poorer neighborhoods. J Abnorm Psychol 109:563–574

Magnusson D (1988) Individual development from an interactional perspective: a longitudinal study. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

Meier MH, Slutske WS, Arndt S, Cadoret RJ (2008) Impulsive and callous traits are more strongly associated with delinquent behavior in higher risk neighborhoods among boys and girls. J Abnorm Psychol 117:377–385

Miethe TD, McDowall D (1993) Contextual effects in models of criminal victimization. Soc Forces 3:741–759

Miller WB (1958) Lower class culture as a generating milieu of gang delinquency. J Soc Issues 14:5–19

Mischel W (1977) The interaction of person and situation. In: Magnusson D, Endler NS (eds) Personality at the crossroads: current issues in interactional psychology. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp 333–352

Mischel W (2004) Toward an integrative science of the person. Ann Rev Psychol 55:1–22

Moffitt TE (1993) Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100:674–701

Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M (2005) Strategy for investigating interactions between measured genes and measured environments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:473–481

Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ (1997) Violent crime and the spatial dynamics of neighborhood transition: Chicago, 1970–1990. Soc Forces 76:31–64

Nagin DS, Paternoster R (1993) Enduring individuals differences and rational choice theories of crime. Law Soc Rev 27:467–496

National Institute on Drug Abuse (1991) National household survey on drug abuse: population estimates. Government Printing Office, Rockville, MD

Osgood DW, McMorris BJ, Potenza MT (2002) Analyzing multiple-item measures of crime and deviance I: item response theory scaling. J Quant Criminol 18:267–296

Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ (1992) Antisocial boys. Castalia, Eugene, OR

Peeples F, Loeber R (1994) Do individual factors and neighborhood context explain ethnic differences in juvenile delinquency? J Quant Criminol 10:141–157

Piquero AR, Moffitt TE, Wright BE (2007) Self-control and criminal career dimensions. J Contemp Crim Justice 23:72–89

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2000) The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime: a meta-analysis. Criminology 38:931–964

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2005) Assessing the relative effects of macro-level predictors of crime: a meta-analysis. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, pp 373–450

Pratt TC, Turner MG, Piquero AR (2004) Parental socialization and community context: a longitudinal analysis of the structural sources of low self-control. J Res Crime Delinq 41:219–243

Raine A (1988) Antisocial behaviour and social psychophysiology. In: Wagner HL (ed) Social psychophysiology and emotion: theory and clinical applications. Wiley, New York, NY, pp 231–250

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods, 2nd edn. Sage, London

Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ (1999) Ecometrics: toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociol Methodol 29:1–41

Raudenbush SW, Johnson C, Sampson RJ (2003) A multivariate, multilevel Rasch model with application to self-reported criminal behavior. Sociol Methodol 33:169–211

Reiss AJ Jr, Rhodes AL (1961) The distribution of juvenile delinquency in the social class structure. Am Sociol Rev 26:720–732

Robins LN (1978) Sturdy childhood predictors of adult antisocial behavior: replications from longitudinal studies. Psychol Med 8:611–622

Rosenfeld R, Messner SF, Baumer EP (2001) Social capital and homicide. Soc Forces 80:283–309

Rountree PW, Land KC, Miethe TD (1994) Macro-micro integration in the study of victimization: a hierarchical logistic model analysis across Seattle neighborhoods. Criminology 32:387–414

Royston P (2005) Multiple imputation of missing values: update. Stata J 5:1–14

Sampson RJ (2006) Collective efficacy theory: lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR (eds) Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. Advances in criminological theory, vol 15. Transaction, New Brunswick, NJ, pp 149–167

Sampson RJ, Bartusch DJ (1998) Legal cynicism and (subcultural?) tolerance of deviance: the neighborhood context of racial differences. Law Soc Rev 32:777–804

Sampson RJ, Groves WB (1989) Community structure and crime: testing social disorganization theory. Am J Sociol 94:774–802

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1994) Urban poverty and family context of delinquency: a new look at structure and process in a classic study. Child Dev 65:523–540

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (1999) Systematic social observation of public spaces: a new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol 105:603–651

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley S (2002) Assessing neighborhood effects: social processes and new directions in research. Ann Rev Sociol 28:443–478

Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush SW (2005) Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. Am J Public Health 95:224–232

Shaw CR, McKay HD (1942) Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Shoda Y, Mischel W, Wright JC (1994) Intraindividual stability in the organization and patterning of behavior: incorporating psychological situations into the idiographic analysis of personality. J Pers Soc Psychol 67:674–687

Silver E (2000) Extending social disorganization theory: a multilevel approach to the study of violence among persons with mental illnesses. Criminology 38:1043–1073

Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Brody GH, Cutrona C (2005) Collective efficacy, authoritative parenting and delinquency: a longitudinal test of a model integrating community- and family-level processes. Criminology 43:989–1029

Snijders TAB, Bosker R (1999) Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage Publications, London

Stark R (1987) Deviant places: a theory of the ecology of crime. Criminology 25:893–909

Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E, Banich M, Graham S, Woolard J (2008) Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: evidence for a dual systems model. Dev Psychol 44:1764–1778

Sutherland EH (1947) Principles of criminology, 4th edn. J. B. Lippincott, Philadelphia, PA

Thornberry TP, Krohn MD (2002) Comparison of self-report and official data for measuring crime. In: Pepper JV, Petrie CV (eds) Measurement problems in criminal justice research: workshop summary. National Academics, Washington, DC, pp 43–94

Tonry MH, Ohlin LE, Farrington DP (1991) Human development and criminal behavior. Springer, New York, NY

Vazsonyi AT, Pickering LE, Junger M, Hessing D (2001) An empirical test of a general theory of crime: a four-nation comparative study of self-control and the prediction of deviance. J Res Crime Delinq 39:91–131

Vazsonyi AT, Cleveland HH, Wiebe RP (2006) Does the effect of impulsivity on delinquency vary by level of neighborhood disadvantage? Crim Justice Behav 33:511–541

Velez MB (2001) The role of public social control in urban neighborhoods. Criminology 39:837–863

Warr M (2002) Companions in crime: the social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge University Press, New York

White JL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Bartusch DJ, Needles DJ, Stouthamer-Loeber M (1994) Measuring impulsivity and examining its relationship to delinquency. J Abnorm Psychol 103:192–205

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK (2005) Validation of the UPPS Impulsive Behaviour Scale: a four-factor model of impulsivity. Eur J Pers 19:559–574

Wikstrom P-OH (1991) Housing tenure, social class and offending. Crim Behav Ment Health 1:69–89

Wikstrom P-OH (2004) Crime as alternative: towards a cross-level situational action theory of crime causation. In: McCord J (ed) Beyond empiricism. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, NJ, pp 1–38

Wikstrom P-OH, Loeber R (2000) Do disadvantaged neighborhoods cause well-adjusted children to become adolescent delinquents? A study of male juvenile serious offending, individual risk and protective factors, and neighborhood context. Criminology 38:1109–1142

Wikstrom P-OH, Sampson RJ (2003) Social mechanisms of community influences on crime and pathways in criminality. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A (eds) Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. The Guildford Press, New York, NY, pp 118–152

Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner-city, the underclass and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Wilson JQ, Herrnstein RJ (1985) Crime and human nature. Touchstone Book, New York, NY

Wolfgang ME, Ferracuti F (1982) The subculture of violence. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from the Project of Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) and was supported by Grant No. 2008-IJ-CX-0006 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, US Department of Justice. Findings and conclusions of the research reported here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the US Department of Justice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zimmerman, G.M. Impulsivity, Offending, and the Neighborhood: Investigating the Person–Context Nexus. J Quant Criminol 26, 301–332 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-010-9096-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-010-9096-4