Abstract

Introduction One possibility for reducing the disabling effects of low back pain (LBP) is to identify subgroups of patients who might benefit from different disability prevention strategies. The aim of this study was to test the ability to discern meaningful patient clusters for early intervention based on self-reported concerns and expectations at the time of an initial medical evaluation. Methods Workers seeking an initial evaluation for acute, work-related LBP (N = 496; 58 % male) completed self-report measures comprising of 11 possible risk factors for chronicity of pain and disability. Outcomes of pain, function, and return-to-work were assessed at 3-month follow-up. A K-means cluster analysis was used to derive patient subgroups based on risk factor patterns, and then these subgroups were compared with respect to 3-month outcomes. Results Eight of the 11 measures showed significant associations with functional recovery and return-to-work, and these were entered into the cluster analysis. A 4-cluster solution met criteria for cluster separation and interpretability, and the four clusters were labeled: (a) minimal risk (29 %), (b) workplace concerns (26 %); (c) activity limitations (27 %); and (d) emotional distress (19 %). Functional outcomes were best in the minimal risk group, poorest in the emotional distress group, and intermediate in the other two groups. A global severity index at baseline also showed highest overall risk in the emotional distressed group. Conclusions Patterns of early disability risk factors from this study suggest patients have differential needs with respect to overcoming emotional distress, resuming normal activity, and obtaining workplace support. Classifying patients in this manner may improve the cost-benefit of early intervention strategies to prevent long-term sickness absence and disability due to LBP.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Institute of Medicine. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC: National Academics Press; 2011.

Ricci JA, Stewart WF, Chee E, Leotta C, Foley K, Hochberg MC. Back pain exacerbations and lost productive time costs in United States workers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(26):3052–60.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR. 2009;58:6.

Pengel LH, Herbert RD, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ. 2003;327(7410):323.

Wolter T, Szabo E, Becker R, Mohadjer M, Knoeller SM. Chronic low back pain: course of disease from the patient’s perspective. Int Orthop. 2011;35(5):717–24.

De Souza L, Oliver Frank A. Patients’ experiences of the impact of chronic back pain on family life and work. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(4):310–8.

Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):581–5.

Linton SJ, Gross D, Schultz IZ, Main C, Cote P, Pransky G, et al. Prognosis and the identification of workers risking disability: research issues and directions for future research. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):459–74.

Hoffman BM, Papas RK, Chatkoff DK, Kerns RD. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain. Health Psychol. 2007;26(1):1–9.

Lambeek LC, van Mechelen W, Knol DL, Loisel P, Anema JR. Randomised controlled trial of integrated care to reduce disability from chronic low back pain in working and private life. BMJ. 2010;340:c1035.

Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ, Morley SJ, Assendelft WJ. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;25(1):CD002014.

Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, Bryan S, Dunn KM, Foster NE, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9802):1560–71.

Foster NE, Hill JC, Hay EM. Subgrouping patients with low back pain in primary care: are we getting any better at it? Man Ther. 2011;16(1):3–8.

Shaw WS, Linton SJ, Pransky G. Reducing sickness absence from work due to low back pain: how well do intervention strategies match modifiable risk factors? J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(4):591–605.

Billis EV, McCarthy CJ, Oldham JA. Subclassification of low back pain: a cross-country comparison. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(7):865–79.

Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, Koes BW, Croft PR, Hay E. Treatment-based subgroups of low back pain: a guide to appraisal of research studies and a summary of current evidence. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(2):181–91.

Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Childs JD. Subgrouping patients with low back pain: evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(6):290–302.

Brennan GP, Fritz JM, Hunter SJ, Thackeray A, Delitto A, Erhard RE. Identifying subgroups of patients with acute/subacute “nonspecific” low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(6):623–31.

Werneke MW, Hart DL, George SZ, Stratford PW, Matheson JW, Reyes A. Clinical outcomes for patients classified by fear-avoidance beliefs and centralization phenomenon. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(5):768–77.

Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, Main CJ. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (“yellow flags”) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):737–53.

Shaw WS, Pransky G, Patterson W, Linton SJ, Winters T. Patient clusters in acute, work-related back pain based on patterns of disability risk factors. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(2):185–93.

Steenstra IA, Ibrahim SA, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Shaw WS, Pransky GS. Validation of a risk factor-based intervention strategy model using data from the readiness for return to work cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(3):394–405.

US Department of Labor—Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational injury and illness classification manual: section 2. 2000. http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshsec2.htm. Accessed 30 July 2007.

American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. Occupational medicine practice guidelines: evaluation and management of common health problems and functional recovery in workers. 2nd ed. 2004. http://www.acoem.org/PracticeGuidelines.aspx. 2011.

Nielsen IK, Jex SM, Adams GA. Development and validation of scores on a two-dimensional workplace friendship scale. Educ Psychol Meas. 2000;60(4):628–43.

Dasinger LK, Krause N, Deegan LJ, Brand RJ, Rudolph L. Physical workplace factors and return to work after compensated low back injury: a disability phase-specific analysis. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(3):323–33.

Kopec JA, Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Abenhaim L, Wood-Dauphinee S, Lamping DL, et al. The quebec back pain disability scale. Measurement properties. Spine. (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(3):341–52.

Davidson M, Keating JL. A comparison of five low back disability questionnaires: reliability and responsiveness. Phys Ther. 2002;82(1):8–24.

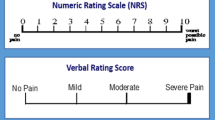

Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain. 1986;27(1):117–26.

Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(11):1331–4.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Geisser ME, Roth RS, Robinson ME. Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory: a comparative analysis. Clin J Pain. 1997;13(2):163–70.

Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–532.

Sullivan MJ, Stanish W, Waite H, Sullivan M, Tripp DA. Catastrophizing, pain, and disability in patients with soft-tissue injuries. Pain. 1998;77(3):253–60.

Kori SH, Miller RP, Todd DD. Kinesiophobia: a new view of chronic pain behavior. Pain Management. 1990(Jan/Feb):9.

Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, van Eek H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62(3):363–72.

Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, Watson PJ. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: a shortened version of the tampa scale for kinesiophobia. Pain. 2005;117(1–2):137–44.

Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):500–7.

Eisenberger R, Fasolo PM, Davis-LaMastro V. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, innovation, and commitment. J Appl Psychol. 1990;75(1):51–59.

Lynch PD, Eisenberger R, Armeli S. Perceived organizational support: inferior versus superior performance by wary employees. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84(4):7.

Byrne ZS, Hochwarter WA. I get by with a little help from my friends: the interaction of chronic pain and organizational support on performance. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11(3):215–27.

Myers SS, Phillips RS, Davis RB, Cherkin DC, Legedza A, Kaptchuk TJ, et al. Patient expectations as predictors of outcome in patients with acute low back pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(2):148–53.

Heymans MW, de Vet HC, Knol DL, Bongers PM, Koes BW, van Mechelen W. Workers’ beliefs and expectations affect return to work over 12 months. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(4):685–95.

Shaw WS, Pransky G, Winters T. The back disability risk questionnaire for work-related, acute back pain: prediction of unresolved problems at 3-month follow-up. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(2):185–94.

Steinley D. K-means clustering: a half-century synthesis. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2006;59(Pt 1):1–34.

Cormack RM. A review of classification. J Roy Stat Soc. 1971;134(3):46.

Steinley D, Brusco MJ. Choosing the number of clusters in kappa-means clustering. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(3):285–97.

Shaw WS, Reme SE, Linton SJ, Huang YH, Pransky G. 3rd place, PREMUS best paper competition: development of the return-to-work self-efficacy (RTWSE-19) questionnaire–psychometric properties and predictive validity. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37(2):109–19.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Case and demographic characteristics for work-related injuries and illnesses involving days away from work (Tables R10, R50–R54). 2000. http://www.bls.gov/iif. Accessed 4 March 2003.

Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr, Shekelle P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478–91.

Burton AK, Balague F, Cardon G, Eriksen HR, Henrotin Y, Lahad A, et al. Chapter 2. European guidelines for prevention in low back pain: November 2004. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(Suppl 2):S136–68.

Kerns RD, Sellinger J, Goodin BR. Psychological treatment of chronic pain. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:411–34.

Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, Vlaeyen JW, Morley S, Assendelft WJ, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7(7):CD002014.

Slater MA, Weickgenant AL, Greenberg MA, Wahlgren DR, Williams RA, Carter C, et al. Preventing progression to chronicity in first onset, subacute low back pain: an exploratory study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):545–52.

Linton SJ, Shaw WS. Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):700–11.

Macedo LG, Smeets RJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, McAuley JH. Graded activity and graded exposure for persistent nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(6):860–79.

Crook J, Milner R, Schultz IZ, Stringer B. Determinants of occupational disability following a low back injury: a critical review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(4):277–95.

Steenstra IA, Verbeek JH, Heymans MW, Bongers PM. Prognostic factors for duration of sick leave in patients sick listed with acute low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(12):851–60.

Franche RL, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):607–31.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a 2006 visiting scholar award to SJ Linton from the Liberty Mutual Research Institute for Safety and a 2006 travel grant from the Scan/Design by Inger and Jens Brun Foundation, awarded to SJ Linton and WS Shaw by the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reme, S.E., Shaw, W.S., Steenstra, I.A. et al. Distressed, Immobilized, or Lacking Employer Support? A Sub-classification of Acute Work-Related Low Back Pain. J Occup Rehabil 22, 541–552 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-012-9370-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-012-9370-4