Abstract

Background The diagnosis of breast cancer increasingly implies a return-to-work (RTW) challenge as survival rates increase. RTW is regarded as a multidisciplinary process and a country’s legislation affects the degree of involvement of the different stakeholders. We elucidated on bottlenecks and contributing factors and the relationship between policy and practice regarding RTW of employees with breast cancer as perceived by Belgian (Flemish) stakeholders. Methods Three multidisciplinary groups (n = 7, n = 9, n = 10) were interviewed during a breast cancer conference. Treating physicians (n = 4), employers (n = 6), social security physicians (n = 3), occupational physicians (n = 4), survivors (n = 5) and representatives of patient associations (n = 4) were included. The major theme was the legal and practical role in the RTW process as experienced by the participants. Qualitative thematic analysis was performed to analyse stakeholders’ experiences of women’s RTW after breast cancer. Results The stakeholders reported different perspectives. Employees focus on treatment and feel ill-informed about the RTW options. Treating physicians do not feel competent about advising on work-related questions. Employers have to balance the interests of both the business and the employee. Social security physicians assess ability to work and facilitate RTW options. Occupational physicians see opportunities but the legislation does not support their involvement. Stakeholders expressed the need for coordination and reported finding ways to accommodate the employee’s needs by being flexible with the legislation to support the RTW process. Conclusions Two factors might hamper RTW for breast cancer patients: the varying stakeholder perspectives and Belgian legislation which emphasizes the patient or disability role, but not the employee role. When stakeholders are motivated they find ways to support RTW, but improved legislation could support the necessary coordination of RTW for these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer diagnosis often occurs during a woman’s professional life and, as recovery rates increase, many employees are confronted with work incapacity and return-to-work (RTW). Returning to work after illness is important from a societal as well as the individual point of view [1, 2]. Many employees with breast cancer do not feel adequately supported in the RTW process [3]. Moreover, these women experience their work incapacity in very different ways, highlighting the need for an individual and flexible approach from all professionals involved in the RTW process [4].

Return-to-work can best be regarded as a multidisciplinary process, involving several stakeholders besides the employee. The reintegration process should ideally be the joint responsibility of all stakeholders in order to improve the quality of RTW support [5–9]. However, stakeholders have different perspectives and usually act according to their own position. Different perceptions of the causes of a patient’s disability and different perceptions about eligible interventions can put stakeholders’ cooperation on RTW under pressure [10].

Legislation is one of the means by which different stakeholder perspectives can be bridged in order to offer patients guaranteed support in RTW. Legislation can prescribe or allow for RTW support and can offer the means to increase facilities for support. Prescriptive legislation can include sanctions to enforce conformity, but the mere existence of RTW legislation might encourage RTW, depending on how favourably the legislation is perceived by stakeholders [11, 12]. As there is no one-to-one relationship between legislation and actual behaviour [11, 12], it is necessary to study the tension between policy and practice in its specific context.

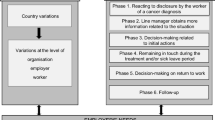

In this paper we focus on the Flemish (Dutch-speaking Belgium) situation. According to van Raak et al. [11] Belgian legislation on sick leave and RTW focuses on ‘provision of information’ and ‘control of sicknesses’. The treating physician, the employer, and the social security physician are the most important stakeholders. The treating physician provides the sickness certificate. The employer pays the sick leave benefit for the first 2–4 weeks. After that, sick leave wages are automatically offered by the national health care and benefit insurance service. Benefit recipients are regularly examined by the social security physician, who evaluates the patient’s inability to work. He assesses the patient’s access to sick leave benefits and gives advice on reintegration possibilities. Both social security physician and employer have to authorize gradual work resumption during sick leave. In Belgium, every employer is obliged by law to organise occupational health care for the employee. Most employers hire the services of an external occupational health care service. A few large companies have an internal occupational health care service. The main role of the occupational physician is to prevent occupational diseases and accidents. The occupational physician is hardly involved in the sick leave process. It is only recently that employees on sick leave have been legally entitled to contact the occupational physician to discuss RTW options. In fact, the move from protection of income to activation has only been made to a limited extent in Belgium [13]. By reviewing the literature, Tiedtke et al. [3] indicated the need to increase and improve stakeholder communication with breast cancer patients. Specific factors involved in supporting RTW of employees with breast cancer appeared to be the physician’s advice on work issues, absence of employer’s or colleagues’ discrimination (job loss, hurtful remarks) and sufficient flexibility in the work environment (gradual assimilation, task modifications).

The aim of this paper is to elucidate the Flemish RTW state of affairs experienced by the stakeholders involved, and to better understand the relationship between RTW policy and practice in the case of employees with breast cancer.

Two research questions will be explored in the Flemish context: (1) What are the bottlenecks and contributing factors that stakeholders experience regarding RTW of employees with breast cancer? (2) Are these experiences affected by legislation, and if so, how?

Methods

Procedure and Sample

In October 2009 stakeholders who attended a local, multidisciplinary breast cancer conference participated in a focus group interview on RTW themes. The invitational conference was aimed at parties involved in the RTW process of breast cancer patients, and delegates from the representative organisations of employers, sickness funds, occupational health care, hospitals, and patient organisations were invited by the Province of Limburg (Flanders) in collaboration with a national cancer foundation. This can be regarded as purposive sampling. Using this occasion for interviews was expected to raise the response rate since these parties do not usually meet to discuss the RTW process for individual patients. In general they act independently. The possibility to confront and exchange their views and experiences was the main reason for us to set up the focus group discussions. The conference consisted of two parts: an informational session in the morning and focus groups in the afternoon. The different groups were announced after the morning session. Participants in the focus groups were invited to be precise about what they actually do and encouraged to respond to each other in order to reduce socially desirable answers. Moreover, we were interested in the participants’ collaboration and conflicts. The focus groups were identified and set up ahead of time by the organizational committee. The following (Flemish) participants were included: treating physicians (n = 4), employers (n = 6), social security physicians (n = 3), occupational physicians (n = 4), and ‘hands-on’ experts i.e. survivors (n = 5) and representatives of patient associations (n = 4). Treating physicians included an oncologist, a gynaecologist, and two general practitioners. The employers’ point of view was represented by human resource or staff managers from large organizations in the profit and non-profit sector. Occupational physicians came from both in-company and external occupational health care services. Social security physicians were from different Flemish Sickness Funds. Patient associations were represented by cancer associations and a professional counselling service. Three multidisciplinary focus groups (n = 7, n = 9, n = 10) were formed, with at least one representative from each discipline. All of the participants had direct experience of treating the employee, managing or supporting RTW of women with breast cancer.

Interviews

Three professional and experienced discussion leaders guided the interviews (duration one and a half hours), using an interview topic guide that was composed by four of the authors (CT, PD, LK, AdR) on the basis of the literature. One of the interviewers was an occupational therapist and co-author of our manuscript. The second interviewer was a managing director of a welfare and health department and the third was a physician. After a general question about the experiences of participants in counselling or treating breast cancer survivors, questions were grouped round two different phases: (1) diagnosis and treatment, and (2) recovery and RTW. The themes in both phases were: role experienced in the disability and RTW process, information and communication, priorities, responsibilities, solutions, duties of care to provide for, barriers and opportunities, and legislation. Three authors (CT, PD, LK) observed the various (simultaneous) focus groups, made observational notes and notes regarding content and synthesized the discussion at the end for the group and a plenary for all focus group members to finish the conference.

Analysis

The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. A qualitative thematic analysis [14] was performed to analyse stakeholders’ experiences with respect to women’s RTW after breast cancer. We used and completed the observational narratives made during the focus groups and processed the data with the research questions in mind. After familiarizing ourselves with the interviews, we initially organised the data per stakeholder according to experiences during treatment, work disability, rehabilitation and (actual) RTW, to capture possible process developments. Constant comparison between data and coding and frequent meetings with the authors led to coding, and identifying themes and their interrelationships. All authors checked the findings and approved the final description. We might consider the various backgrounds of the authors (social scientists, insurance physician, occupational physician and occupational therapist) and the fact that five authors had a research background, three of these in qualitative research, as a reliable safeguard. To avoid bias, the co-author who collected the data from one focus group was only involved in the final process of data-analysis. For the sake of participant anonymity, all participant accounts (except for the employees) were referenced as a mix of ‘he’ and ‘she’. As the focus groups were conducted in Dutch, the quotes were translated into English by a professional translator.

Ethical Considerations

We received informed consent for participation (and recording) from all stakeholders. Moreover, neither the identity of the stakeholder nor the organization to which he or she belongs is reported in the paper.

Results

Stakeholders’ Perspectives Regarding RTW

We found a large variety of perspectives within and amongst all stakeholder groups.

Employees: From Feelings of Uncertainty to Confidence and Hope

For the employees of the focus groups, the period of their breast cancer diagnosis is uncertain and emotionally difficult. Life stagnates and control over life seems to be lost; it is a chaotic period. The participating women with breast cancer report that initially they have to deal with the diagnosis and start treatment. Most of them stop working immediately. Others stay (part-time) at work out of a sense of loyalty to employer and colleagues, or for financial reasons (especially self-employed women, according to a treating physician). Disclosing the diagnosis is an important moment and most women have strong feelings about their experiences, which range from a supportive environment to discriminating attitudes from colleagues, who do not know the diagnosis, but base their reaction on the long period of time that the employee is on sick leave and the fact that the employee in question does not have to work until further notice.

“…and then you call the office to say that you’ll be sick until the end of the year at least, and their reaction is: ‘that long’!; it felt like sparks of envy sputtering from the phone…” (Patient)

Most employees become compliant patients and generally follow their physicians’ instructions during frequent consultations. Contact with the health insurance company, after 3 months of illness, is experienced only as a means of regulating their sick leave. During this phase, some of the women miss having a confidential, capable and empathetic advisor.

As time goes by, many employees might regain confidence and new hope for the future. Then the first work-related questions arise. Employees might feel doubtful about their ability, concerned about their jobs, and inadequately informed about RTW options. Some of the employees experience that the employer suggests returning only when they are fully capable, which is felt as a painful and conflicting message. Other employees report that they would have liked independent advice during this phase, as well as a supportive environment and practical help on how to organise RTW.

Treating Physicians: From Guiding Treatment to Feelings of Incompetence

After an employee has been diagnosed, the treating physician has to write a sick note. Physicians report immediately starting a strictly timed and intensive treatment plan including therapeutic support. They expect patients to follow their instructions.

“…the basic message we give is: now this and that and this, now it is treatment time and then we’ll do that, and indeed, your life will be lived. At that moment hospital takes over your life…” (Oncologist)

The treatment also includes sickness certification as mentioned in the introduction. During treatment, treating physicians might declare a woman totally unable to work. Once treatment has finished, treating physicians want to stimulate patients’ RTW, but they reported having a lack of knowledge on RTW procedures and possibilities. In addition, they often feel ill-equipped to advise on work-related issues and might therefore refer the women to the occupational physician.

“…when the patient asks: ‘what’s your opinion about returning to work’? I’ll always answer: talk to your occupational physician to see if your work situation allows for your return, I cannot assess your job risks, I don’t know what work you do and if it might make your condition worse…” (Oncologist)

Employers: From Distant to Ambiguous Involvement

The employers who participated in the focus groups reported feeling suddenly and unexpectedly confronted with the employee’s breast cancer diagnosis and short- to long-term sick leave. They have to take care of the sick leave paperwork and ensure the continuation of the employee’s work. Employers feel ambiguous about the sick leave phase as they have to balance the interests of the business and the employee, in the latter case by showing empathy and patience. They are nevertheless afraid of negative reactions if they contact the employee during sick leave. Although no employer–employee contact is required by law during sick leave, some employers mention striving for optimal and open communication with their employee, to ensure a less complicated RTW later on. When an employee wants to return to work part-time, with recommended adjustments to the job, this might create a dilemma for employers if they have arranged for a full-time and motivated replacement.

“…labour costs start from the moment the substitute has to stay for a while till the person who returns to work gradually takes over all her job responsibilities. Sometimes you know the latter will not be able to fully take over. As a human being you understand at the time, but at some moment you will wonder, how long can I tolerate this with respect to the other colleagues? So initially there is a clear understanding that they need to take care of themselves and have enough time to cure, there is a clear understanding. But after a while, the moment they are back in the circle, people around become frustrated, as I noticed, and I regret that, but it is really difficult to cope with…” (Employer)

Employers can question the timing of RTW. Legally, the employee has to inform the employer 1 day before returning to work. Attentive employers like to prepare reintegration and thus need more time, particularly when contact with the other stakeholders has been limited.

Social Security Physicians: From Assessing to Helping and Guiding

As mentioned in the introduction, social security physicians are informed about the employee’s absence by means of a certified diagnosis from the treating physician. The social security physicians report that they stay in the background during the first months of work incapacity. They are qualified to inform, assess, and advise, in addition to providing a supportive role. However, the other stakeholders often seem to be unaware of this role.

“…actually, from the start we try to support the patient and to refer them to possible treatment. Often we suggest a psychologist, often people are not aware of those possibilities. In case of practical problems they can go to a social worker, just things we also do. Other things we can do is inform them about legislation on health insurance and partial return to work. Initially these are the things we usually do,…” (Social security physician)

“…as social security physicians, we developed a new task interpretation last year, and indeed we have to give information on all options. The first contact is an information session; we also cautiously sound out the employee a little. So since last year this is officially included in our range of duties…” (Social security physician)

The social security physicians report that their role becomes more visible as recovery progresses. In general, after a few months, they have to assess the employee’s ability to work, although this is considered too early by some social security physicians in the case of breast cancer diagnosis. By discussing the employee’s legal RTW options, occupational retraining might also be considered. However, some social security physicians mentioned that they do not want to dash all the employee’s hopes of returning to their former job. Furthermore, they have to legally consider and agree on all RTW options.

“…in case of a progressive return, we as social security physicians decide on the length of the ‘progressive’ and sometimes this might be years, as I said when we talked about disability benefit. But I do not think it is expedient to allow someone the ‘progressive’ today, and depending on the illness I will not allow ‘progressive’ for half a year. No, it is for a 6–8 week period. After that period I will see the patient again and ask how things are going and we’ll see whether or not it has to be continued…” (Social security physician)

Social security physicians expressed a real desire to discuss RTW with the occupational physician at an earlier stage, but they are often confined by both practical and legal obstacles.

Occupational Physicians: From Limitations to Opportunities

Most of the participating occupational physicians had mixed feelings about their role concerning employee’s RTW. They see opportunities but feel they are not supported by legislation legitimizing their involvement. External company physicians in particular feel seriously overloaded with the RTW administrative support, particularly after an employee’s sudden return, and they tend to stick to their legal role, which is to decide within 8 days whether the employee is capable of doing their former job again.

“…it is a practical problem, I won’t fully absolve the occupational physician from that, but we are under great pressure and the moment we see a patient, we would like to decide as quickly as possible in favour of the person. If we put it off, this will increase the pressure of work and we currently have a shortage of physicians, which is in fact a practical problem so I hope you’ll understand our position…” (Occupational physician)

During sick leave occupational physicians report that they generally have to wait for the employer’s notification about the employee’s initiative to return to work. As a rule the first legal contact, a compulsory resumption consultation, occurs within the first week after the employee’s return, but it is too late to provide good support. As mentioned, during this contact all potential hurdles have to be instantly removed, usually in consultation (by telephone) and in agreement with the employer. However, the participating occupational physicians have the feeling that they could offer important added value if counselling and support for RTW were legally endorsed earlier.

“…I believe that we occupational physicians could play an essential role here. Actually, I see the occupational physician in a central position. We can easily contact all parties involved, we are allowed to. We can contact health insurance, we can contact the general practitioner, we can contact the employer, we should know the job demands, we can assess job capacity, or we should be able to. And then I think, we could be the intermediary to facilitate the return to work…” (Occupational physician)

In-company physicians usually feel more closely involved in the sick leave policy as they have more opportunities to contact the employer and employee. They also have easier access to an employee’s health status. Some occupational physicians, however, expressed serious reservations and contradictory feelings about employers’ attitudes to RTW and their unwillingness sometimes to consider adapting the job. While fully understanding the employers’ point of view, they would like employers to receive positive rewards for being more accommodating as regards the work.

“…for some handicaps there is a compensation for wage costs for the employer. What I experience in reality is that the employer weighs up the costs of a Petri dish [i.e. every little cost to the smallest detail] and if it is too expensive or if he has to pay more than what he believes to be the output, the measures I advise are often refused. Should we, in case of reintegration…certainly the employer should get an incentive for arranging certain adaptations…” (Occupational physician)

Understanding and Sympathy for the Stakeholder’s Role and Perspective

During the focus interviews the stakeholders recognized the divergent perspectives and spontaneously came up with ideas to prevent difficulties in the multidisciplinary collaboration. Participants discussed the need for information (brochures) and coordination in order to ensure fair and high-grade employee reintegration after breast cancer treatment.

“…as for the real support: I noticed, because at first I feared the stories I would hear, about the medical stuff and wondered if I would be able to understand them. But very often we are very much on the same line but focusing very differently. I also believe we should cooperate between the various fields to focus on the process we see, by getting to know each other better and to know what each of us is doing that appears to be useful. So, I found this a good part of the day, but I think it shouldn’t end here…” (Representative patient organization)

All participants brainstormed (and elaborated) on how to arrange meaningful and structured contact at an earlier stage, agreeing that this is an important and practical issue in the RTW process. Some suggested that a competent intermediary or employment officer would be useful to bring all the stakeholders together, whereas others opted for an amendment to the law.

“…we should have someone who can connect the companies and the patients and who can get the information on employer’s possibilities and patient’s capabilities, and then maybe a middle course has to be adopted…” (Representative patient organization)

Role of Legislation

All stakeholders in the focus groups feel they should support the RTW process but some report that the current legislation does not explicitly prescribe this role. The legislation appears only to marginally address RTW and consequently guidance and advice on RTW is not an explicit part of their daily work. Moreover, some stakeholders confirmed that legally binding (occupational) decisions can only be made after actual RTW. However, stakeholders feel they have and use the opportunities to support RTW, even if this implies being flexible with the law.

Narrow Orientation on RTW

Proceeding to legislation, the experience of some stakeholders in the focus groups is that there are few supportive incentives to promote RTW after breast cancer. Legislation seems to focus completely on compensation by defining different roles (employee role, patient role, and disability role) and their legal requirements, instead of on participation in work. Some stakeholders report that in practice the patient role or disability role, rather than the employee role, is emphasized.

According to the interviewees, legislation does not protect the employee role. First, the employer has no obligation to provide compensation, after the benefit for the initial 2–4 week absence. Secondly, the employer is perfectly entitled to end the employment contract by discharging the employee for medical reasons or for sustained sick leave.

“…we are from the working sector, and we have the six-month rule, which means that the employer is allowed to discharge the patient for medical reasons or for long-term absence and that concerns those patients. But mostly this happens in smaller companies, in large companies this won’t happen. We often see this happening in small supermarkets, with only one or two employees. Those really will be discharged, because the employers have to pay social financial contributions twice. In addition, they have to replace the absent employee to keep the store open. So, we see distressing situations, they occur, but fortunately not too often…” (Social security physician)

Thirdly, in the case of RTW, the employment contract will be resumed on conditions ultimately decided by the employer who weighs the employee’s capacity against organizational concerns. After having been unable to work for a year, a (breast cancer) patient is eligible for long-term disability benefit. As mentioned by some interviewees, this can form another threat to the employee role, because patients often (wrongly) interpret this as becoming permanently work-disabled. In Belgian legislation however, the notion of long-term disability benefit does not imply a permanent disability and patients are expected to return to work when possible.

As mentioned by many stakeholders, the RTW process is unstructured, complicated and slow. Employees may initiate their RTW, but assessment of the former job by the insurance practitioner is only possible after 6 months. Financial support for the employer (e.g. for work modifications) is eligible 6 months after an employee’s official disability benefit qualification. Employees with breast cancer might worry about their capability, but an application for social welfare payment is felt to be a prolonged career barrier. Moreover, employers feel confronted with practical and implementation barriers.

“…we know the measure but you have to be able to practically implement it. The measure is meant to allow people to set their own pace more or less. But on the other hand we have to follow the regulations, saying: you have to ask for an hourly financial contribution if you send someone from your service. Then it is very difficult to explain to your customers that when (ever) that person comes, she is allowed to work more slowly, because she is a person with that kind of status, but you have to pay just as much. That is not always viable, not even if you are a well-meaning employer and willing to adapt the work rhythm. You have to consider the existence of your organization and the positions you create…” (Employer)

Returning to regular duties is preferred over part-time work resumption by some employers because it means other colleagues don’t have to make up for the ‘losses’. Some reported that there also seems to be no clear legal solution for patients with permanent limitations who wish to resume part-time work for a long period or even for the rest of their professional career.

“…I would just like to add, I think a lot of employers are aware of a lot of the existing possibilities, but not willing to invest in employing employees with complex, emotional, physical or any problems. It requires observance, it requires willingness, and it requires good communication within the team, especially when you are working in a team. Your team has also to accept this, so it is a lot more complicated than just knowing…” (Employer)

Stakeholders report that it is difficult to implement work modifications to support RTW. Many occupational physicians are not informed in good time about the medical situation of the employee and a good relationship with the employer seems to be particularly important to ensure sufficient cooperation. Moreover, decisions regarding work modifications can only be taken after the employee’s RTW. All arrangements have to be made at a moment’s notice.

“…you know the legislator decides. We can only examine people when they return to work, the day they return. Sometimes we see them earlier, but those are just informal contacts, which makes it impossible to print a form or make a decision. So, if we would play our part, which we would like to, our intermediary role, adapting and so on, it would indeed be desirable for the legislation on that point to change, so that people could visit us before they return to work and so that we, between the reintegration and the moment they visit us, could try to reorient or advise the employer. But now, because legislation dictates that we can only see people the moment they return to work, it really restricts the time in which we can act…” (Occupational physician)

Tailoring to Employee Needs: Stretching the Rules

The interviewees recognized the importance of RTW and subsequently some reported having been creative as regards the law and pushing the boundaries. Social security physicians may anticipate the RTW moment by postponing the formal insurance decision and refer to the occupational physician before benefit has ended. In addition, to smooth the part-time RTW option, social security physicians may get tough when ‘deliberating’ with the stakeholders, because there are no simple or general rules.

“…on the other (hand) it is not without engagement, but you can’t take it as a general rule. It is a process between the patient and the social security physician, and the occupational physician and the employer. And in my opinion it is a kind of process which can lead to discussion, to achieve the best option, which can go well. But sometimes it is tough…” (Social security physician)

In harmony with the social security physician’s anticipatory and deliberating role, some occupational physicians in turn indicate having special or ‘dual’ interests in a good relationship with the employer to discuss RTW options and encourage the re-employment of a not-fully performing employee.

“…a conversation with the employer is very important, because a good relationship between the occupational physician and the employer will render some goodwill, for it is the employer’s goodwill that makes him re-employ a person who doesn’t perform 100%. And that’s a very important point and if we have a good relationship with the employer, you can achieve more, he will listen to your arguments, in contrast to someone he does not have a good relationship with…” (Occupational physician)

As the interviewees reported, occupational physicians often need to be creative and confer with the absent employee on RTW options. Some strive to create a win–win situation for the employer and the employee and would prefer legal incentives for a cooperative employer, instead of having to encourage him to cooperate.

“…I would like to see a legal framework so we can see the people earlier, to discuss their return to work. Now we handle this creatively, but this is the Belgian way of arranging things, so to speak. I would prefer a legal framework. Secondly, I would like to have some tools, also a reward for the employers who are willing to make adjustments. Because if you want to change something, you have to create a win–win situation and we can only achieve that when the employer sees a profit balance…” (Occupational physician)

Choosing to postpone the starting date for the legal check-up before RTW and to advise the employee to prolong her legal absence is another way of stretching the rules for some occupational physicians in the focus groups.

“…and that again is in the employee’s personal interest, yes, she is at work, there is no solution for her and then she is often told: we have nothing, stay home as from tomorrow. And then she has been working for one day, and then you’ll have to deal with all that red tape. You can avoid all this, by telling them the day before, that you still haven’t found a solution and that they have to come back in another two weeks…” (Occupational physician)

Some participating employers try to find their own creative RTW solutions, e.g. compensating an employee’s part-time resumption by putting aside a full-time year budget to continue paying the replacement, or to outweigh the disadvantages.

“…everything is geared to full-time department equivalents. They have to be fully (100%) employable and if someone joins who only manages 50%, the others have to cover the 50% loss, but they don’t have time for this (…) I believe under these circumstances you have to create room in the budget, either within your policy, because I cannot imagine that the authorities will reserve money for this, we would make good progress then (…) Then it would be much easier for those people to take action, and they could return to work earlier, that’s why we deal with year-based full-time equivalents…” (Employer)

Discussion

In a qualitative study in the Flanders’ region of Belgium, we studied stakeholders’ experiences regarding RTW of breast cancer survivors and how these are affected by legislation.

The relevant key findings are: (1) stakeholders’ varying perspectives develop over time; (2) legislation does not stimulate RTW, and (3) stakeholders are flexible with the legislation to support RTW. They need to be creative to cooperate in supporting RTW. The findings demonstrate specific tensions between policy and practice.

First we will discuss the differing and developing perspectives. Employees focus on treatment and generally feel supported by the employer during the early stage of sick leave. After recovery they are insecure about their capability and employers’ support for RTW and they would like independent advice. Treating physicians focus mainly on the patient’s health. After ending the employee’s treatment, they report a lack of knowledge about RTW procedures. Employers hardly contact the employee during sick leave and move to ambiguous involvement in later stages. They steer a middle course between empathy for the employee and business interests. Social security physicians await recovery and become more involved after a few months. They have to assess the ability to work and facilitate RTW options. Occupational physicians are not usually involved during sick leave. They have to confirm the employee’s health for their former job, but see opportunities to support RTW at an earlier stage.

Differences between stakeholder perspectives on RTW are reported for various countries [9, 11, 15]. A Swedish study demonstrated that employers valued early problem identification and early stakeholder action, since stakeholders are by law responsible for organizing RTW [16]. Recently Maiwald et al. [10] pointed out the differences between stakeholder perceptions on workplace-based interventions to reduce sick leave in a Canadian setting. Although differences in their approach to work disability were found, they also discovered that the stakeholders compromised on common interventions for different reasons [10].

In the USA, Young et al. [6] described stakeholders’ RTW motivations, interests and concerns. Although relevant, the study is only based on document analysis. Stakeholders (employees, employers, health care providers, payers and society) had different, but also shared goals, as they were interested in employees’ potential and in ways to assist them. Stakeholders may have conflicts, but they are motivated to cooperate as long as they can expect benefits and less opposition to their own goals. In the end they all profit from a timely, safe and successful RTW [6]. To establish shared goals Brunarski et al. [15] discussed the need to build capacity for sustaining collaboration, since stakeholders outside the workplace do not consider themselves as part of a RTW team, with responsibilities to communicate with each other [15]. Knowing and accepting the differences seems to be an important prerequisite to establishing collaboration. Despite the different perspectives, stakeholders may thus reach a compromise.

Our findings particularly underlined the stakeholders’ wish to know each other and to cooperate in order to achieve a qualitatively good RTW and to share responsibility for the RTW process. However, they noticed that successful RTW in Flanders largely depends on employers’ goodwill and the employer’s relationship with the occupational physician and the employee. In actual fact, employers have to make efforts to create acceptable RTW conditions. MacEachen et al. [17] extracted the key concept ‘trust and goodwill’ from 9 out of 13 reviewed studies. Goodwill affects the level of creativity among stakeholders [17].

Secondly, we studied whether and how these experiences are affected by legislation according to the stakeholders. Legislation appears to be able only very partly to bridge different perspectives and support RTW. This is because the Flemish legislation emphasizes compensation and protection of the patient role and provides far less means to stimulate work reintegration and a return to the employee role. Thirdly, if stakeholders are creative and willing to push the boundaries and stretch the rules, the Flemish legislation does not get in the way of the RTW aim. Nevertheless, it seems advisable to include more support for RTW in legislation. In fact, the principle of early RTW before full recovery has to be accepted [17] and the main focus of the legal framework might need to shift from compensation to activation, which is emphasized as common practice in several countries [13]. Our findings also seem relevant to the RTW process beyond breast cancer. Generally, an activation policy seems to be preferred above compensation policy [18]. However, activating RTW too early might cause a relapse and there is a need to balance protection and activation in order to achieve sustainable RTW [10, 18].

Many stakeholders in our study are intrinsically motivated to implement RTW effectively. This might reflect the Flemish standard regarding the importance of RTW. In an earlier study, van Raak et al. [11] found that even though The Netherlands had more obligatory rules regarding sick leave guidance than Belgium, the Belgian legislation was more effective because stakeholders were intrinsically more motivated [11]. It might be advisable to stimulate employers’ positive decisions on modifications, to appoint a RTW coordinator, or to create legal possibilities to decide on RTW options during sick leave in Flanders. Moreover, further discussion between stakeholder groups about the current tension between policy and practice might lead to improved legislation in order to support RTW.

Effective RTW support has to answer to employee needs and employer interests in combining capabilities and job demands to create a win–win situation for both stakeholders. The role of the workplace seems to be crucial. To support RTW of breast cancer employees, a pro-active employer-based approach with early intervention is needed, to achieve a safe and early return and to accommodate employees who experience limitations [19, 20]. In a review of disability management, improvement in communication between stakeholders was found to be responsible for successful RTW interventions [21]. In 2002 the lack of employer involvement was recognized in The Netherlands and the far reaching Gatekeeper Improvement Act (the Dutch WVP) was introduced. This mandates greater employer involvement and incentives: employers have to pay sickness benefit for at least 2 years. By using employment support programmes if necessary, employers have to prove they did everything to help the sick employee to RTW [13]. Registered data from a Dutch Health service show that partial RTW after breast cancer has increased since 2002 (employer’s compensation for 1 year). However, this might not depend exclusively on policy changes [22].

The current Flemish situation offers opportunities for employees to make the first move to RTW. We found that all favourably disposed and motivated stakeholders also take initiatives to support RTW, and some stakeholders (social security and occupational physician) exert their influence to use the rules creatively. In a similar vein, Tjulin et al. [23] emphasized the role of all workplace parties involved during the different phases of RTW (off work, back to work, sustainability of work). Interactions of goodwill were described, based on treating the employee as one (a colleague) would want to be treated him- or herself [23]. Absence of goodwill, however, and giving priority to business interests undermine the employee’s motivation to cooperate during RTW [17]. This implies that in cases of less cooperative employers or co-workers, legislation that demands efforts to establish RTW seems necessary.

The question is whether complex multidisciplinary collaboration is essential for good quality of care during the RTW process. Franche et al. [5] mentioned that straightforward RTW can occur with minimal involvement of stakeholders; however, colleagues’ support is essential in overcoming obstacles. Moreover, in the optimal self-organized RTW, the worker is asked what she needs by the employer [5]. In the Canadian study [17] evidence was found that injured employees are expected to be self-reliant, but instead they might feel vulnerable and unsure about RTW procedures. In a similar vein, there is a question as to whether it is reasonable and feasible to expect breast cancer survivors to take the initiative during sick leave. A general answer seems hard to give because of the large variation in experiences. In an earlier study [4] we found that the experiences of women (employees) as regards being work disabled due to breast cancer varied widely. Three main types of experiences were distinguished: a ‘disruption’ with irreparable loss, an ‘episode’ after which life continues as before, and a ‘meaningful period’ after which new life priorities are set. Perhaps only the women who experience their breast cancer period as an episode might be capable of initiating straightforward RTW [4].

There seems to be hardly any research explicitly investigating the role of legislation in a qualitative design and many studies lack the degree of information and specificity of our (small-scale) study. Høgelund [24] compared The Netherlands and Denmark, using panel-data on long-term sick-listed workers and found different consequences (for work-disabled persons and labour participation) of the Dutch private responsibility and the Danish public authority’s responsibility. Strong and legal ties between the employer and the employee (Dutch policy) enhance RTW of long-term sick-listed employees. Dutch employers, however, refrain from employing persons with a high risk of falling ill, whereas Denmark has high labour participation rates for all groups in society [24]. Anema et al. [25] analysed cross-sectional data on RTW after chronic occupational back pain from six different countries and demonstrated larger RTW rates in countries applying work interventions and less strict criteria for entitlement to disability benefit. However, these two quantitative studies did not aim to link the varied stakeholders’ perspectives with legislation.

The qualitative design of our study and the specific attention to the role of legislation thus allowed a nuanced understanding of stakeholders’ experiences. All of the participants had direct experience of treating the employee, managing or supporting RTW of women with breast cancer, which increases the validity. The strength of this study is the sample issue and the degree of information. All relevant stakeholders and representatives from multiple organizations participated in the focus groups, which is an added value. However, stakeholders were not necessarily representative for their entire professional group, moreover they were all Flemish. It would be interesting to explore the findings in the Walloon provinces of Belgium.

All participants in our study had a positive attitude towards RTW, which may be a serious selection bias; however, they showed us the opportunities to affect RTW. In contrast, patients brought in many negative experiences. Therefore, the reality in Belgium might be even more varied than reported in this paper.

Conclusions

Our study explored the bottlenecks and contributing factors experienced by Flemish RTW stakeholders and how legislation affects their behaviour. Similar to other studies from different countries, stakeholders vary regarding their perspective on the importance of RTW. Even though the current legislation does not encourage RTW, motivated stakeholders can positively affect RTW. This study showed that in anticipation of legal RTW policy changes and decisions, motivated and creative stakeholders can support fair RTW by stretching the rules. In addition to improving legislation to encourage work interventions and less strict compensation policies for entitlement to disability benefits [24], stakeholder motivation to support RTW might be positively influenced by publishing good practices and best cases.

References

Vingård E, Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Consequences of being at sick leave. Scand J Public Health. 2004;563:207–15.

Van Oostrom SH, Driessen MT, De Vet HC, Franche RL, Schonstein E, Loisel P, et al. Workplace interventions of preventing work disability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;15:2. CD006955.

Tiedtke C, De Rijk A, de Casterlé BD, Christiaens MR, Donceel P. Experiences and concerns about returning to work for women breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:677–83.

Tiedtke C, de Casterlé BD, De Rijk A, Christiaens MR, Donceel P. Breast cancer treatment and work disability: patient perspectives. The Breast. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2011.06.002.

Franche RL, Baril R, Shaw W, Nicholas M, Loisel P. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: optimizing role of stakeholders in implementation and research. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:525–42.

Young AE, Wasiak R, Roessler RT, McPherson KM, Anema JR, Van Poppel MN. Return to work outcomes following work disability: stakeholder motivations, interests and concerns. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4). doi:10.1007/s10926-005-8033-0.

Mortelmans AK, Donceel P, Lahaye D. Disability management through positive intervention in stakeholders’ information asymmetry. A pilot study. Occup Med. 2006;56:129–36. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqj014.

Gobelet C, Luthi F, Al-khodairy AT, Chamberlain MA. Vocational rehabilitation: a multidisciplinary intervention. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1405–10.

Shaw W, Hong Q, Pransky G, Loisel P. A literature review describing the role of return-to-work coordinators in trial programs and interventions designed to prevent workplace disability. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18:2–15. doi:10.1007/s10926-007-9115-y.

Maiwald K, De Rijk A, Guzman J, Schonstein E, Yassi, A. Evaluation of a workplace disability prevention intervention in Canada: examining differing perceptions of stakeholders. J Occup Rehabil. 2010. doi:10.1007/s10926-010-9267-z.

Van Raak A, De Rijk A, Morsa J. Applying new institutional theory: the case of collaboration to promote work resumption after sickness absence. Work Employ Soc. 2005;19:141.

De Rijk A, Van Raak A, Van der Made J. A new theoretical model for cooperation in public health settings: the RDIC model. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:1103.

Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers, a synthesis of findings across OECD countries. OECD report. France; 2010.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Brunarski D, Shaw L, Doupe L. Moving toward virtual interdisciplinary teams and a multi-stakeholder approach in community-based return to work care. Work. 2008;30:329–36.

Larsson A, Gard G. How can the rehabilitation planning process at the workplace be improved? A qualitative study from employers’ perspective. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13:169–81.

MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche R-L, Irvin E. The workplace based return to work literature review group. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:257–69.

MacEachen E, Ferrier S, Kosny A, Chambers L. A deliberation on ‘hurt versus harm’ logic in early-return-to-work policy. Policy Pract Health Saf. 2007;5:75–96.

Williams R, Westmorland M. Perspectives on workplace disability management: a review of the literature. Work. 2002;19:87–93.

Rosenthal D, Hursh N, Lui J, Isom R, Sasson J. A survey of current disability management practice: emerging trends and implications for certification. RCB. 2007;50:76–86.

Pransky GS, Shaw WS, Franche RL, Clarke A. Disability prevention and communication among workers, physicians, employers, and insurers—current models and opportunities for improvement. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:625–34.

Roelen CA, Koopmans PC, van Rhenen W, Groothof JW, van der Klink JJ, Bültmann U. Trends in return to work of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:237–42.

Tjulin A, MacEachen E, Ekberg K. Exploring workplace actors experiences of the social organization of return-to-work. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:311–21.

Høgelund J. Reintegration: public or private responsibility? Consequences of Dutch and Danish policies toward work-disabled persons. Int J Health Serv. 2002;32:467–87.

Anema JR, Schellart AJ, Cassidy JD, Loisel P, Veerman TJ, van der Beek AJ. Can cross country differences in return-to-work after chronic occupational back pain be explained? An exploratory analysis on disability policies in a six country cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:419–26.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Flemish Cancer League (VLK). The Province of Limburg and the Limburgse Kanker Samenwerking (LIKAS) participated in organizing the breast cancer conference.

Conflict of interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tiedtke, C., Donceel, P., Knops, L. et al. Supporting Return-to-Work in the Face of Legislation: Stakeholders’ Experiences with Return-to-Work After Breast Cancer in Belgium. J Occup Rehabil 22, 241–251 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9342-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9342-0