Abstract

Introduction Long-term sickness absence is a major public health and economic problem. Evidence is lacking for factors that are associated with return to work (RTW) in sick-listed workers. The aim of this study is to examine factors associated with the duration until full RTW in workers sick-listed due to any cause for at least 4 weeks. Methods In this cohort study, health-related, personal and job-related factors were measured at entry into the study. Workers were followed until 1 year after the start of sickness absence to determine the duration until full RTW. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were used to calculate hazard ratios (HR). Results Data were collected from N = 730 workers. During the first year after the start of sickness absence, 71% of the workers had full RTW, 9.1% was censored because they resigned, and 19.9% did not have full RTW. High physical job demands (HR .562, CI .348–.908), contact with medical specialists (HR .691, CI .560–.854), high physical symptoms (HR .744, CI .583–.950), moderate to severe depressive symptoms (HR .748, CI .569–.984) and older age (HR .776, CI .628–.958) were associated with a longer duration until RTW in sick-listed workers. Conclusions Sick-listed workers with older age, moderate to severe depressive symptoms, high physical symptoms, high physical job demands and contact with medical specialists are at increased risk for a longer duration of sickness absence. OPs need to be aware of these factors to identify workers who will most likely benefit from an early intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Long-term sickness absence is a major public health and economic problem [1]. Although the vast majority of all sickness absences is short-term, longer absences disproportionally contribute to the costs of sickness absence [1]. Long-term sickness absences account for more than a third of total work loss days and up to 75% of absence costs [1]. Furthermore, longer sickness absences are associated with a reduced probability of return to work (RTW) [1]. Besides economic consequences, long-term sickness absence has severe consequences for the worker. Long-term sickness absence increases the risk of social isolation, reduces meaningful activity and may make the worker doubting his own competence [2, 3].

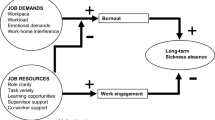

Sickness absence and RTW are both complex, multifactorial phenomena, which are not only related to biomedical factors but also influenced by a wide variety of personal and job-related factors [4–6]. In the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), disability and functioning are viewed as outcomes of interactions between health conditions and contextual factors, encompassing personal and environmental factors [7]. Studies that examined prognostic factors for sickness absence often focused on the onset of sickness absence and on specific disorders [5, 8–11]. However, evidence is lacking for factors that are associated with the duration until RTW in workers sick-listed due to any cause. In a recent systematic review, Dekkers-Sanchez et al. [5] identified 16 factors that were significantly associated with long-term sickness absence in workers sick-listed for at least 6 weeks. Because most factors were studied in only one study and only two factors were studied twice, strong evidence for any of these factors could not be established. Weak evidence was found for associations between older age and history of sickness absence with long-term sickness absence. Other person-related and job-related factors, such as poor general health, mental health disorders, low income and lack of skill discretion, were insufficiently studied [5].

In a Dutch cohort study of workers, previous sickness absence was only related to a longer duration until RTW if that previous sickness absence episode was due to similar complaints as the current sickness absence episode [12]. Moreover, workers sick-listed due to psychological symptoms had the longest duration until RTW, compared to those sick-listed due to musculoskeletal problems and other physical health problems [12]. In addition, behavioral determinants (low work attitude, low willingness to expend effort in RTW and low social support) and job-related determinants (high supervisor support, low co-worker support and working in public administration, construction, financial and commercial services, transport or educational sector) were related to a longer duration until RTW [13, 14]. In a longitudinal study with a 2-year follow up among workers sick-listed for at least 3 weeks, Hoedeman et al. [15] found high levels of somatic symptom severity, health anxiety and older age to be associated with a longer duration of sickness absence.

In order to get a better understanding of RTW and to support the development of interventions aimed at RTW, it is necessary to identify factors that are associated with the duration of sickness absence in sick-listed workers. In the Netherlands, entitlement for a disability pension is determined after a maximum of 2 years of sickness absence. In those 2 years, the worker and employer are both responsible for activities aimed at RTW. Workers are obliged to visit an occupational physician (OP) in the first 6 weeks of sickness absence, who advices on RTW based on a multifactorial problem analysis. The multifactorial problem analysis is conducted by the OP to assess the risk on long-term sickness absence, and contains information on the type of problems, whether the worker receives treatment and the private, work and social context. Based on this analysis, a RTW plan including work adjustments and other interventions has to be made. Thus, assessment of prognostic factors for RTW at this time is of particular importance in the Dutch system. The cause of sickness absence may not always be clear at that point in time and the worker and OP may disagree about the cause of sickness absence. Moreover, RTW is not only influenced by medical factors, but also by personal and job-related factors, and therefore, identifying factors predicting RTW in workers sick-listed due to any cause is relevant. The objective of the present study was to study the association of health related, personal and job-related factors with the duration until full RTW in workers on sickness absence for at least 4 weeks.

Methods

Design and Study Population

This is a prospective, longitudinal study in which data collected in the recruitment phase of a randomised clinical trial (RCT) were used. Aim of that RCT, of which the design is described elsewhere, was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of a Collaborative Care treatment in sick-listed workers with major depressive disorder (MDD) [16]. The recruitment was conducted in collaboration with a large, Dutch occupational health service (OHS), covering about 15% of the total Dutch working population. In order to recruit participants for the RCT, workers on sickness absence between 4 and 12 weeks due to any cause were send a questionnaire, accompanied by written information about the study and an informed consent form [16]. Workers who were still on sickness absence were asked to fill in the questionnaire. It was not possible to check whether workers who did not respond to the questionnaire were still sick-listed, which makes it impossible to provide a reliable response percentage of the recruitment procedure. In the first screening wave, the complete baseline questionnaire was sent to screen eligible workers, which was later adapted by only sending the screener for depressive symptoms. In this study, data were used from the first screening wave, comprising the comprehensive questionnaire. In the present study, workers on sickness absence for at least 4 weeks due to any cause were included. Workers with a major depressive disorder who participated in the RCT were excluded from this study, as well as workers on sickness absence due to pregnancy-related health problems. Furthermore, workers who were no longer absent from work when filling in the questionnaire were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the VU University Medical Center.

Measures

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this study is the duration until full RTW, starting from the first day of sickness absence. Full RTW was defined as the first full RTW with equal earnings, lasting for at least 4 weeks. In accordance with the Dutch Health Law, two sickness absence episodes with less than 4 weeks of full RTW in between, were counted as a single absence episode. The duration of sickness absence was censored at 1 year after the start of sickness absence. Data were censored for workers whose sickness absence ended because they resigned [17]. Sickness absence data were derived from the OHS register.

Independent Variables

In line with the ICF model, the independent variables in this study include health-related, personal and job-related factors. The independent variables were collected by self-report at entry into the study.

Health-Related Factors

Chronic medical illness was measured with the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) list, a questionnaire containing 28 conditions [18]. The CBS list was dichotomized into (0) no chronic medical condition and (1) at least one chronic medical condition. Physical symptoms were measured with the Physical Symptoms Checklist (Lichamelijke Klachten Vragenlijst, LKV), a 51-item checklist assessing the number and intensity of functional somatic symptoms [19]. This measure ranges from 0 to 51 and was dichotomized, with scores of five or more coded as (1), referring to high physical symptoms [20]. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) was used to measure depression, anxiety (including generalized anxiety and panic) and somatization [21]. The depression scale of the PHQ, the PHQ-9, ranges from 0 to 27 and was dichotomized, with scores above nine coded as (1), referring to moderate to severe depressive symptoms [22, 23]. The somatization scale of the PHQ, the PHQ-15, ranges from 0 to 30 and was dichotomized, with scores above nine coded as (1), referring to medium to high somatization [24]. The generalized anxiety scale and the panic scale of the PHQ both result in dichotomous variables, with workers classified as having, respectively, generalized anxiety or panic disorder coded as (1) [21].

Personal Factors

Participants provided information on demographics such as age, gender, marital status and educational level. Age was dichotomized into (0) ages 18 to 44 and (1) ages 45 or above. Marital status was dichotomized into (0) not married/cohabiting and (1) married or cohabiting. Educational level was categorized into three categories, ranging from (0) low (including primary school, lower vocational education and lower secondary school), to (1) moderate (including intermediate vocational education and upper secondary school), to (2) high (including upper vocational education or university) [25]. Health care utilization in the past 3 months was measured with the Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness (TiC-P) and included contact with an OP, a general practitioner (GP), a mental health professional, a medical specialist, a paramedic, a social worker and contact with alternative medicine [18]. These variables are from a different order than the other factors in this study, in that people with high health care utilization will often have the worst outcomes, not so much because health care would be detrimental for them, but because it reflects a more severe condition. The variables on health care utilization were dichotomized into (0) no health care visit in the past 3 months and (1) at least one health care visit in the past 3 months. Previous sickness absence was derived from the OHS register and was assessed with two variables: the number of absence episodes in the past 2 years and the number of absence days in the past 2 years. The number of absence episodes was dichotomized, with two absence periods or more coded as (1), referring to a high number of absence episodes. The number of absence days was dichotomized, with 28 absence days or more coded as (1), referring to a high number of absence days.

Job-Related Factors

Job-related factors were measured with five scales from the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ), which were dichotomized based on the highest quartile of the range of the scale [26]. Decision latitude, consisting of 9 items, ranges from 24 to 96 and was dichotomized with scores above 78 coded as (1). Psychological job demands, including 5 items and ranging from 12 to 48, was dichotomized with scores above 39 coded as (1). Physical job demands, a 5-item scale ranging from 5 to 20, was dichotomized with scores above 17 coded as (1). Social support, encompassing co-worker and supervisor support, is an 8-item scale ranging from 8 to 32, which was dichotomized with scores above 26 coded as (1). Finally, job insecurity, a 3-item scale ranging from 3 to 12, was dichotomized with scores of nine or higher coded as (1).

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed two, consecutive steps. First, potential factors were selected through univariate analyses for all variables and the duration until full RTW. Factors that showed an association with the outcome measure with a P-value <.20 were selected for the next step, the backward Cox proportional hazard regression model. Non-significant factors were manually eliminated until the regression model only contained factors with P-values <.05. Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated for these factors. Interaction terms between the associated factors were also tested for significance. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by plotting the log minus log plot. All analyses were adjusted for the duration of sickness absence at entry into the study. The analyses were performed with SPSS 15.0 software.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

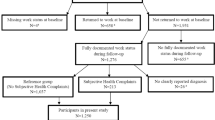

Data were collected from N = 730 sick-listed workers. N = 10 workers were excluded because they participated in the RCT, N = 145 workers were excluded because they were no longer absent from work when completing the questionnaire, and N = 13 workers were excluded because of sickness absence due to pregnancy-related health problems. The remaining N = 562 workers were included in this study, as indicated in the flowchart (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. A total of N = 399 (71%) participants had lasting, full RTW within 1 year after the start of sickness absence. Fifty-one participants (9.1%) were censored because they resigned from work and the remaining N = 112 (19.9%) participants did not have lasting, full RTW during follow-up.

Factors Associated with the Duration Until Full RTW in Long-Term Sick-Listed Workers

The following factors had an association of P > .20 in the univariate analyses and were therefore excluded from the backward Cox proportional hazard regression model: marital status, educational level, panic, decision latitude, job insecurity, contact with OP, contact with mental health professional in the past 3 months, the number of absence episodes in the past 2 years and the number of absence days in the past 2 years.

Table 2 shows the results of the final model. HRs and 95% confidence intervals are presented, with HRs smaller than 1 representing a longer duration until RTW. The results show that high physical job demands, contact with medical specialists, high physical symptoms, moderate to severe depressive symptoms and older age are associated with a longer duration until RTW in sick-listed workers. Table 3 shows the, unadjusted, median durations until RTW for the subgroups of workers scoring low or high on the associated factors. For illustrative purpose, the Kaplan–Meier curve for an associated factor, physical job demands, is shown in Fig. 2. There were no significant interaction terms.

Discussion

Main Findings

In the present study, factors associated with the duration until full RTW were examined in workers on sickness absence for at least 4 weeks due to any cause. The results showed that high physical job demands, contact with medical specialists, high physical symptoms, moderate to severe depressive symptoms and older age were significantly associated with a longer duration until RTW in workers on sickness absence longer than 4 weeks.

Comparison Findings with Other Studies

In this study, physical job demands and contact with a medical specialist showed the strongest associations with the duration until RTW. With regard to the importance of job-related factors, studies so far showed inconsistent results. Although physically demanding work and low control over the work situation have often been found to be related to the onset of long-term sickness absence, evidence was lacking for the association with the duration of sickness absence in sick-listed workers [27–32]. In the present study, physical job demands were found to be related to the duration until RTW, but the relationship with the duration until RTW could not be found for decision latitude. Moreover, physical symptoms were associated with the duration until RTW. These results suggest that the physical condition of the worker and the physical demands in a job are more important for the duration until RTW when sick-listed than factors such as job control and social support. Furthermore, the statistical significance of ‘having had contact with medical specialists in the past 3 months’, while controlling for physical symptoms and conditions, shows that when workers seek specialist care, this is associated with a longer duration until RTW. Visiting a medical specialist may reflect a more severe condition, but it might also imply that having specialist care keeps workers at home, waiting for a diagnosis or treatment [33]. Also, although previous studies found depressive symptoms to be associated with the onset of sickness absence and a longer duration of sickness absence in short-term sick-listed workers, it was not known whether this association would be present as well in workers sick-listed due to any cause [9, 10, 34]. The results of the present study show that in a population of sick-listed workers, moderate to severe depressive symptoms are related to a longer duration until RTW. This suggests that regardless of the initial cause of sickness absence, depressive symptoms such as a depressed mood, decreased self-esteem and social isolation will probably hinder the RTW process. Finally, the finding that older age was a significant factor for the duration until RTW confirmed previous research [5, 15]. It is interesting to note that previous sickness absence in the past 2 years was not significantly related to the duration until full RTW, while this has often been found to be an important prognostic factor for the (re-)occurrence of sickness absence [5, 12, 35, 36]. This contrasting result may be explained by differences in study populations and differing definitions of previous sickness absence. For instance, in a prospective Norwegian study among long-term absentees, only previous sickness absence longer than 20 weeks significantly increased the disability risk [37]. Post et al. [12] also studied the duration until RTW in sick-listed workers and found previous sickness absence to be an important factor only when that previous sickness absence was due to similar health conditions as the current sickness absence episode. In Hoedeman et al. [15] as well, previous sickness absence, assessed in days and in number of periods, was not associated with the duration until RTW in workers sick-listed for at least 3 weeks. Our results confirm those of Hoedeman et al. [15] and suggest that previous sickness absence per se, regardless of the cause of that previous sickness absence, is not an important factor for the duration until RTW in sick-listed workers.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is the focus on workers sick-listed due to any cause, because knowledge on the RTW of this population is scarce. Moreover, factors were included from multiple domains, covering health-related, personal and job-related factors. However, these factors were measured only at entry into the study, it is thus unknown what happened in the period between entry into the study and RTW. Another strength of the present study is the record linkage of our health-related, personal and job-related data with sickness absence data from the OHS register [17, 34]. The exclusion from this study of depressed workers who participated in the RCT may have lead to bias by excluding a population in which particularly depressive symptoms may have been important for the duration until RTW. However, of the initial 730 workers of whom we had data, we excluded only ten workers because of their participation in the RCT.

Practical Implications and Further Research

One year after the start of sickness absence, 19.9% of the workers was still absent from work. When conducting the problem analysis, OPs need to be aware of the factors that are associated with a longer duration until RTW in sick-listed workers in order to identify workers who will most likely benefit from an early intervention. By intervening timely on modifiable factors, permanent work disability may be prevented. The findings of the present study suggest that high physical job demands in workers on sickness absence may indicate a need for early work(place) modifications aimed at (temporarily) reducing the physical demands in a job [38]. Active stakeholder involvement of at least the worker and the employer is recommended in this type of intervention [38, 39]. OPs who work in sectors with high physical job demands, such as the construction industry, should pay extra attention to this aspect. When workers visit a medical specialist, it is important that the OP and specialist discuss functional limitations and possibilities for activation and RTW. However, communication between OPs and treating physicians is limited and is hampered by the fact that both have different goals when treating the same patient [33]. Screening for depressive and physical symptoms in sick-listed workers may support OPs in identifying workers at risk for a longer duration of sickness absence. A validated instrument for the screening and monitoring of depressive symptoms is the PHQ-9 [22, 23]. Because a reduction in symptoms does not automatically lead to RTW, specific cognitive behavioural interventions aimed at both RTW and reducing depressive symptoms might be desirable for these workers [16, 40]. The LKV might be used as a screening instrument for physical symptoms, but further research is needed on that [19]. Like in the treatment of depressive symptoms, a focus on RTW is needed in the treatment of physical symptoms in order to achieve a more rapid RTW. However, there is often a lack of attention to work-related problems in curative care. More education on this issue may lead to a better focus of treating physicians on work and RTW and may facilitate communication with OPs [33, 41, 42]. Given the importance of both physical and depressive symptoms, it would be interesting for future research to include the ‘intention to RTW despite having symptoms’ as potential factor associated with the duration until RTW. Previous research has indicated the importance of this intention in a population of sick-listed workers with distress [43]. Perhaps workers focus much on the severity of their symptoms when considering RTW, which may hinder the RTW process. For future research it would also be interesting to include repeated measurements of the potential associated factors to describe the process until full RTW in more detail. Moreover, a longer follow-up on sickness absence data would be interesting to asses full RTW after the first year of sickness absence and to include recurrent sickness absence as an outcome measure.

Conclusion

In sum, in this study high physical job demands, contact with medical specialists, high physical symptoms, moderate to severe depressive symptoms and older age were identified as factors associated with a longer duration until RTW. OPs need to take these factors into consideration when conducting the problem analysis and sickness guidance of sick-listed workers.

References

Henderson M, Glozier N, Holland EK. Long term sickness absence. BMJ. 2005;330(7495):802–3.

Bowling A. What things are important in people’s lives? A survey of the public’s judgements to inform scales of health related quality of life. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1447–62.

Bilsker D, Wiseman S, Gilbert M. Managing depression-related occupational disability: a pragmatic approach. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(2):76–83.

Loisel P, Durand MJ, Berthelette D, Vézina N, Baril R, Gagnon D, et al. Disability prevention. New paradigm for the management of occupational back pain. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2001;9(7):351–60.

Dekkers-Sanchez PM, Hoving JL, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. Factors associated with long-term sick leave in sick-listed employees: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(3):153–7.

Labriola M, Lund T, Christensen KB, Kristensen TS. Multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors as predictors of return to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48(11):1181–8.

World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health. ICF. 2002. Geneva.

Steenstra IA, Verbeek JH, Heymans MW, Bongers PM. Prognostic factors for duration of sick leave in patients sick listed with acute low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(12):851–60.

Lotters F, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Burdorf A, Pole JD. The prognostic value of depressive symptoms, fear-avoidance, and self-efficacy for duration of lost-time benefits in workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(12):794–801.

Duijts SF, Kant I, Swaen GM, van den Brandt PA, Zeegers MP. A meta-analysis of observational studies identifies predictors of sickness absence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(11):1105–15.

Lagerveld SE, Bultmann U, Franche RL, van Dijk FJ, Vlasveld MC, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM et al. Factors associated with work participation and work functioning in depressed workers: A systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2010.

Post M, Krol B, Groothoff JW. Self-rated health as a predictor of return to work among employees on long-term sickness absence. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(5):289–97.

Brouwer S, Krol B, Reneman MF, Bultmann U, Franche RL, van der Klink JJ, et al. Behavioral determinants as predictors of return to work after long-term sickness absence: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(2):166–74.

Post M, Krol B, Groothoff JW. Work-related determinants of return to work of employees on long-term sickness absence. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(9):481–8.

Hoedeman R, Blankenstein AH, Krol B, Koopmans PC, Groothoff JW. The contribution of high levels of somatic symptom severity to sickness absence duration, disability and discharge. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20(2):264–73.

Vlasveld MC, Anema JR, Beekman AT, van Mechelen W, Hoedeman R, Van Marwijk HW, et al. Multidisciplinary collaborative care for depressive disorder in the occupational health setting: design of a randomised controlled trial, cost-effectiveness study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:99.

Koopmans PC, Roelen CA, Groothoff JW. Sickness absence due to depressive symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81(6):711–9.

Hakkaart-van RL. Manual Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for costs associated with psychiatric illness [in Dutch]. Rotterdam: Institute for Medical Technology Assessment; 2002.

van Hemert AM. Physicial Symptoms Questionnaire [In Dutch: Lichamelijke Klachten Vragenlijst]. Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum. 2003.

de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, van Hemert AM. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470–6.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–44.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1194–201.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–66.

Verweij A. Categorisation of educational level [In Dutch: Indeling opleidingsniveau]. Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning, Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid. Bilthoven: RIVM; 2008.

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The job content questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):322–55.

Allebeck P, Mastekaasa A. Swedish council on technology assessment in health care (SBU). Chapter 5. Risk factors for sick leave—general studies. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2004;63:49–108.

Roelen CA, Weites SH, Koopmans PC, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW. Sickness absence and psychosocial work conditions: a multilevel study. Occup Med (Lond). 2008;58(6):425–30.

Lund T, Labriola M, Christensen KB, Bultmann U, Villadsen E. Physical work environment risk factors for long term sickness absence: prospective findings among a cohort of 5357 employees in Denmark. BMJ. 2006;332(7539):449–52.

Lund T, Labriola M, Christensen KB, Bultmann U, Villadsen E, Burr H. Psychosocial work environment exposures as risk factors for long-term sickness absence among Danish employees: results from DWECS/DREAM. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(11):1141–7.

Bang CK, Lund T, Labriola M, Villadsen E, Bultmann U. The fraction of long-term sickness absence attributable to work environmental factors: prospective results from the Danish work environment cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64(7):487–9.

Nielsen ML, Rugulies R, Christensen KB, Smith-Hansen L, Kristensen TS. Psychosocial work environment predictors of short and long spells of registered sickness absence during a 2-year follow up. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48(6):591–8.

Anema JR, Van Der Giezen AM, Buijs PC, van MW. Ineffective disability management by doctors is an obstacle for return-to-work: a cohort study on low back pain patients sicklisted for 3–4 months. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59(11):729–33.

Bultmann U, Rugulies R, Lund T, Christensen KB, Labriola M, Burr H. Depressive symptoms and the risk of long-term sickness absence: a prospective study among 4747 employees in Denmark. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(11):875–80.

Koopmans PC, Roelen CA, Groothoff JW. Risk of future sickness absence in frequent and long-term absentees. Occup Med (Lond). 2008;58(4):268–74.

Dewa CS, Chau N, Dermer S. Factors associated with short-term disability episodes. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(12):1394–402.

Gjesdal S, Ringdal PR, Haug K, Maeland JG. Predictors of disability pension in long-term sickness absence: results from a population-based and prospective study in Norway 1994–1999. Eur J Public Health. 2004;14(4):398–405.

van Oostrom SH, Driessen MT, de Vet HC, Franche RL, Schonstein E, Loisel P et al. Workplace interventions for preventing work disability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD006955.

Anema JR, Steenstra IA, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, Knol DL, Loisel P, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for subacute low back pain: graded activity or workplace intervention or both? A randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(3):291–8.

Blonk RW, Brenninkmeijer V, Lagerveld SE, Houtman ILD. Return to work: a comparison of two cognitive behavioural interventions in cases of work-related psychological complaints among the self-employed. Work & Stress. 2006;20:129–44.

Anema JR, Jettinghoff K, Houtman I, Schoemaker CG, Buijs PC, van den Berg R. Medical care of employees long-term sick listed due to mental health problems: a cohort study to describe and compare the care of the occupational physician and the general practitioner. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(1):41–52.

van der Feltz CM, Hoedeman R, de Jong FJ, Meeuwissen JAC, Drewes HW, van der Laan NC, et al. Faster return to work after psychiatric consultation for sicklisted employees with common mental disorders compared to care as usual. A randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychiatric Dis Treat. 2010;6:375–85.

van Oostrom SH, van MW, Terluin B, de Vet HC, Knol DL, Anema JR. A workplace intervention for sick-listed employees with distress: results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(9):596–602.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Work Disability Prevention CIHR Strategic Training Program, through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant(s) FRN: 53909. This study was financially supported by the Foundation for Innovation of Health Insurers (‘Innovatiefonds Zorgverzekeraars’) in the Netherlands.

Conflict of interests

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Vlasveld, M.C., van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M., Bültmann, U. et al. Predicting Return to Work in Workers with All-Cause Sickness Absence Greater than 4 Weeks: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Occup Rehabil 22, 118–126 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9326-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9326-0