Abstract

Parental support is of paramount importance in the promotion of positive parenting, strengthening parenthood and protecting children from disadvantages due to immigration experiences. The aim was to describe what is known about parent support programmes targeted to families who are immigrants. Electronic databases and the grey literature were systematically and comprehensively searched with no time/language restrictions. JBI approach and PRISMA-ScR were used to guide the review. N = 88 articles were sourced. Interventions were targeted to improve parental practices, skills and family wellbeing, usually through group-based methods. Most interventions included components of positive parenting and family communication. Identifying the needs of the target group and cultural tailoring were reported to be highly important in gaining acceptability, promoting engagement and producing benefits. Parent support programmes for families who are immigrants potentially improve positive parental practices and families’ wellbeing. There are many applicable and effective interventions to be exploited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, more than 70 million people worldwide have been forcibly displaced from their homes. Over 25 million of these forcibly displaced people are refugees and the majority of them are children under the age of 18 [1]. Moving to another country is a stressful process and a major life change for anyone but is something that can negatively affect children in particular [2,3,4,5]. Severe stress is harmful during early childhood when the developing brain is very sensitive to environmental influences [3]. During the ‘refugee experience’ parental presence and support are of paramount importance in protecting children from negative physical and psychosocial symptoms [3, 6]. In reality, caring and protective parenting can be threatened due to a variety of negative influences in terms of the resettlement process and pre-migration experiences [7]. This review is not limited to including only studies with refugees, since we focus on all forcibly displaced people. Although these populations face similar acculturation challenges, the migration process of refugees might include more traumatic experiences. However, all forcibly displaced might be in e need to receive parent support, and therefore all forcibly displaced are in the focus of the current review.

Migration and the resettlement process are both associated with many stressors. These stressors, include the psychological strain or distress of the migratory experience and the acculturation process, with consequences for mental health. For example, it has been estimated that the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among migrants (i.e. refugees and labor migrants) is 47% [5, 8] and in war-affected children who are refugees 30.4% [9]. The prevalence percentages do however vary greatly across studies being 19.0–52.7% for PTSD, 10.3–32.8% for depression, 8.7–31.6% for anxiety disorders and 19.8–35.0% for emotional and behavioural problems [10]. Nevertheless, it is clear that these multiple stressors and the possibly that the less responsive caregiving of offspring, increases the risk of developing health problems and psychopathology in children who are refugees [3, 9,10,11,12,13,14]. Family-based approaches, such as parent support programmes are suggested as a way to improve children's emotional and behavioural problems [15]. As such, there is a clear and urgent need for better evidence-supported information about parenting support methods for immigrant families to ensure health equality and access to support [6].

Parent support programs are defined as programs that are aiming to strengthen and support parenting abilities and promote new competencies so that parents have the skills and knowledge needed to conduct child-rearing practices [16, 17]. Parent support programs are also aiming to enable parental competencies that promotes providing their children experiences and opportunities which promote child learning and development [16]. In this review, by parent support programs we also mean those methods and programs that are targeted to parents and which are aiming to improve parent’s and children’s health and wellbeing and to prevent maltreatment and abuse of their children. The included studies must contain a family/parent component meaning that the intervention must be targeted solely or partly to parent/s who are immigrants.

Preliminary searches conducted in October 2019 revealed that little is known about parent support programmes targeted at immigrant and refugee populations. In 2017, The Lancet Psychiatry published a call for parenting interventions for mothers who are refugees to promote the healthy development of their children younger than 3 years [6]. This petition also certifies the need for evidence in parenting support programmes for immigrant families. As our initial search for reviews on this topic support the thesis that the evidence base for parent support programmes for immigrant families seems to be fragile [4, 6], we decided to conduct a scoping review in order to gather and summarise existing knowledge in this field and to provide a broad view of what is known about the topic to date.

The aim of this scoping review is to describe what is known about parent support programmes targeted at families who are immigrants. The results of this review will help in targeting, developing, utilising and implementing new methods in child and family services to support parents who are immigrants. The main review question is answered in relation to the next four clarifying questions: (1) to what purpose are the parent support programmes targeted, (2) how were the participants reached, (3) what components do these parent support programmes include, and (4) what outcomes and results have the parenting support programmes demonstrated (if any).

Methods

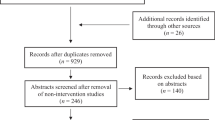

This scoping review was conducted according to the guidance provided by JBI [18] including the application of a PRISMA-ScR statement [19]. The review questions were formulated based on the applicable parts of the template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist [20]. The search strategy used and the study selection process are illustrated in the Flow chart (Fig. 1). The protocol was registered prior to conducing the literature searches in Open Science Framework (OSF 2019-11-01). Since this is a review article, there was no need for ethical approval from the institutional and/or national ethical review committee.

Search Strategy and Data Sources

The databases Academic Search Premier (EBSCO), Web of Science, PsycINFO (EBSCO), PubMed/Medline, CINAHL, ERIC (EBSCO), Cochrane Library, and Medic (Finnish database) were searched for relevant literature (11/2019). OpenGray was searched for the relevant ‘grey’ literature. Search terms were identified through an initial search and all identified keywords and index terms were utilised across all included databases. The search terms included such as emigrants, immigrants, emigration, immigration, refugees, asylum seeker, displaced person, displaced people, parenting, parents, caregivers, parent–child relations, family, mother, father, guardian, parent support program, parenting support program, parent support, parenting support, parent program, parenting program, parent training, parenting training, parent intervention, parenting intervention, parent education, parenting education, family support, family program, family training, family intervention, family education, social support, health promotion, counselling, support, program, training, intervention as Main Heading (Descriptors) and free word queries. The full search strategy and queries are presented in Online Appendix 1. The search was conducted together with an information specialist.

Study Selection

The study selection was at all stages of selection performed based on the inclusion criteria. First, the titles and abstracts were screened and thereafter the full texts of the selected articles. The selection process was conducted by two independent reviewers. Disagreements between the two reviewers were solved by discussion and consensus or by the decision of a third reviewer [18].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed using the PCC- model where P is for population, C for concept and C for context [18]. In this review, the population of interest is first generation immigrant parent(s) with a child/children under 18 years of age. The key concept of this review is parent support programmes. Parent support programmes are defined as programmes that aim to strengthen and support parenting abilities and promote new competencies so that parents have the skills and knowledge needed to conduct child-rearing practices. Parent support programmes also aim to enable parental competencies that promote the provision of their children with experiences and opportunities which promote child learning and development [16]. The included studies must contain a family/parent component meaning that the intervention must be targeted solely or partly to parent(s) who are immigrants. In this review, the context of interest is the new host country including health and social care settings, school, kindergarten, community, jail, refugee centres, detention centre, immigration detentions, refugee camps, home and remote/digital environments. The new host country should be classified as an upper-middle-income economy or high-income economy (HIC) based on the World Bank criteria [21]. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

A total of 2047 original reports and articles were identified through the selected databases and 103 additional records were identified through OpenGray. After removing duplicates, 1259 records were screened by title and abstract and 125 full-texts eventually screened. A total of 88 reports and articles were included in the final analysis.

Data Charting

The JBI approach and PRISMA-ScR were used to guide data charting and the reporting of the results. A data charting table (Online Appendix 2) was made and tested before its use by the researchers. Information was collected on the author(s), year of publication, publication/study country, aim of the study or report, study methods, study population and key findings (if applicable). The data charting table was collated by two researchers .

Data Analysis/Synthesis of Results

Data was analysed using the narrative synthesis method, an approach often utilised when the included studies are heterogeneous in terms of methods, participants or data [18, 22]. Frequencies were computed to describe particular details.

The narrative synthesis of evidence was undertaken by grouping the studies by their methodology, interventions (parent support programmes) and participants. After that, we further summarised the interventions based on the research questions and summarised their purposes, recruitment strategies, procedures, delivery methods and tailoring. In addition, the benefits of the parent support programmes’ (research question 4) were summarised based on the selected studies’ methodology. NVivo 11 (QSR International 2020) was used in data handling and analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the Selected Studies

A total of N = 88 articles were included in this review. The majority of the studies were conducted in North America. The countries of origin are reported in Fig. 2. In two studies, the first author affiliation was in USA but the intervention was conducted in another country (Thailand and Turkey) [23, 24].

Most of the parent support programmes were targeted at parents with a Latin American cultural background (n = 32) [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. The cultural background of the participants or target participants in parent support programmes is reported in Fig. 3. In a total of 18 studies, the study participants were from mixed cultural backgrounds or the cultural background was not specified [4, 54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] (Fig. 3).

The study methods of the included studies are reported in Fig. 4. Most of the studies were qualitative (n = 20) [26, 31, 39, 42, 49, 57, 68, 70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] and RCT studies (n = 18) [23, 34, 36, 38, 44, 58, 64, 83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93]. A total of 14 of the studies lacked a clear methods section or the methods were inadequately reported [27, 28, 30, 32, 33, 45, 55, 56, 59, 66, 94,95,96,97] (Fig. 4).

Recruitment of the Participants

Participants were recruited into parent support programmes through community-serving agencies/organisations [25, 26, 33, 57, 72, 80, 84, 96, 98,99,100,101] and local communities [23, 26, 31, 35, 36, 44, 50, 68, 71, 73, 74, 80, 82,83,84, 88, 89, 92, 94, 96, 102,103,104,105]. Research and parent support programme information was shared in the community for example by distributing flyers [39, 56, 98,99,100, 104,105,106,107] or via direct invitation (in-person contact or personal contact by phone) by local community leaders, health workers, religious leaders, interpreters, research coordinators, researchers, school counsellors or teachers [32, 39, 50, 71, 80, 84, 98]. In addition, studies also recruited participants from public services e.g. kindergarten [55, 64, 70, 76], schools [29, 30, 32, 33, 37, 38, 40, 56, 58, 72, 80, 84,85,86,87, 90, 94, 95, 104], language schools [73, 74, 107, 108], churches or religious organisations [80, 94, 105, 109, 110], social services, or through social worker [29, 38, 84,85,86,87, 104], child welfare services [84], health care clinics [36, 44, 50, 54, 55], mental health services or through mental health worker [44, 49, 50, 58, 71, 85, 104, 105], initial registration centre [78] and child protective services [85, 95, 104]. Some studies reported using social media [98], television [28], radio [100, 107] and newspaper advertisements/invitations [28, 100, 106]. A word-of-mouth strategy was also much used to recruit participants [28, 36, 44, 62, 80, 84, 89, 101, 105,106,107].

Personal invitations were seen as effective strategies in recruitment, including word-of-mouth and direct invitations by community leaders or service providers [80, 84]. Bilingual communication was seen as important [84]. Community members were also seen as important links between the parent support programme providers and the target participants. In many studies, community members were engaged in several roles and at different phases of the programme and worked as interventionists, research assistants, and/or as community advisory board members [92].

Identified Interventions to Support Immigrant Parents

A total of 14 interventions were studied two times or more in original studies or reports and two study protocols were designed to use the same intervention. These 14 interventions were Padres Informados/Jóvenes Preparados (PI/JP) [25, 31, 98], Happy Families Program (HFP) (adapted from the Strengthening Families Program) [23, 88], Generation PMTO (Parent Management Training- Oregon model) [43,44,45, 83, 84], Supported Playgroups [57, 68], Caregiver Supported Intervention (CSI) [102, 103] and incredible years [58, 73, 74, 85, 95], CAPAS-Original/CAPAS-Enhanced (based on PMTO) [36, 45, 105], Family Communication [38, 39], Connect- Programme (Ladnaan- programme = Connect- programme + information on Swedish society) [75, 86, 87], Familias Unidas [40, 41], Migrant Education Event Start (MEES) [47, 48], Social Support Intervention [81, 100], Fortalezas Familieares (FF): Family Strengths [49,50,51] and Coffee and Family Education and Support (CAFES) [93, 101]. These interventions are presented (rationale of intervention, methods to reach participants, intervention procedures and materials, delivery of intervention and tailoring) in Table 2, and synthesised in the following sections. A total of 33 interventions appeared just once and the names and rationales of these interventions are presented in Table 3.

Rationales of Interventions

The parent support programmes were generally targeted either to support [23, 49,50,51, 57, 68, 81, 88, 93, 100, 101], enhance [58, 73, 74, 85, 95] or to strengthen [36, 44, 45, 105] parental skills and parenthood [102, 103] or to prevent youth [25, 31, 40, 41] and children’s [43,44,45, 71, 83, 84] behavioural problems. Interventions were also targeted at enhancing family communication [38, 39], strengthening the parent–child relationship [75, 86, 87] and enhancing parental involvement in children’s education [47, 48]. Notably, the Connect-programme [75, 86, 87] was extended to the Ladnaan-programme which aimed also to provide information about the Swedish social- and healthcare system along with the Connect-programme. It was also seen as important that refugee parents got to know the policies and practices of their new host country. Parental support programmes also had various indirect aims and, for example, PI/JP intervention [25, 31, 98] aimed to prevent substance use among youths by improving parental skills.

Components of the Interventions

Interventions were mainly well designed and structured. Methods used in the delivery of the interventions were versatile, including demonstrations [23, 88] and problem-solving [43,44,45, 71, 83, 84], online- and video-material [58, 73, 74, 85, 95], conversations [25, 31, 98] and discussions [38, 39, 75, 86, 87], exercises in the group sessions [25, 31, 98], homework [38, 39, 43,44,45, 58, 71, 73, 74, 83,84,85, 95], roleplaying [23, 25, 31, 88, 98] and social activities [57, 68]. The purposes of the tasks and materials were, for example, to strengthen positive parenthood and build relational and communicational skills with children [58, 73, 74, 85, 95], encourage positive behaviour [43,44,45, 71, 83, 84], and offer emotional and social support [54, 89]. Materials were tailored to be suitable for each target population. Online-materials were offered if participants were hindered in terms of physically participating in the actual parent support programme sessions [25, 31, 98].

Most of the interventions (FF, PI/JP, HFP, PMTO, incredible years, CAPAS, family communication, connect-programme, social support intervention) included, on average, 6 to 18 weekly sessions while the duration of these sessions varied between 1 and 2.5 h. In some interventions (PI/PJ, HFP, CAPAS, Connect-Programme), sessions included lunch, dinner or a snack and beverages, since it was seen as important that parents and children had the possibility to eat together [23, 44, 45, 88, 105]. Meals were prepared by paying attention to the families’ cultural background [23, 49,50,51, 88] and in that way it was possible to show respect for their culture(s). In some studies, the duration of the intervention was tailored based on needs (supported playgroups), or school year (MEES). Interventions were generally delivered in group format and if participants were parents and children (especially youths), they had both separate and shared group sessions. In some cases, male and female participants had separate groups. In the Connect-programme, childcare services were offered during sessions to ensure parents’ participation [75, 86, 87].

The intervention providers were most often called facilitators [25, 31, 36, 44, 45, 57, 68, 98, 105], trained group leaders [58, 73,74,75, 85,86,87, 95], or peer-mentors [81, 100]. Most of these providers had some kind of cultural link to the target population and their culture, e.g. providers were bicultural or bilingual [25, 31, 98]. In some cases, the proficiency in the host country’s language was an inclusion criterion for participation [64, 73] or the intervention was delivered in two main languages of participants (for example English and Spanish) [39]. Also matching volunteers and participants based on participants’ preferred language or grouping participants based on language was done by intervention providers [54, 57]. Most often the interventions were bilingual [29, 32,33,34, 39, 50, 51, 57, 74, 83, 84, 99, 106, 111], and some of them also aimed to educate in language skills [47, 48, 61]. Some interventions were delivered solely in the participants’ native language [73, 75, 80, 93, 101, 107, 110] or used layman or professional interpreters [56, 58, 59, 71, 78]. It was also seen as important that providers had appropriate education and work experience. Providers’ gender was also mentioned as being an important consideration (Familias Unidas, Social Support Intervention, CAFES). In some cases, the physical location of the intervention delivery was also mentioned. In these cases, most often the intervention was delivered in communal settings, like schools [58, 73, 74, 85, 95], community-agencies [25, 31, 98] or in co-operation with local community-based organisations [57, 68]. CAPAS-intervention was delivered in local religious organisation establishments. Overall, it was seen as important to deliver the intervention in places which are neutral, feel safe and are accepted by the target population.

Tailoring of the Interventions

Cultural tailoring was commonly used to tailor interventions for suitability in relation to target populations. Tailoring was related to the intention to participate, acceptability, adherence and to reduce dropouts. Few studies however reported on the methods used to conduct cultural tailoring and in those studies that did report on this aspect it was generally via either a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach [25, 31, 98] or a qualitative approach [23, 43,44,45, 71, 83, 84, 88]. The purpose of cultural tailoring was to ensure that interventions identify the needs of the target population and is suitable from a linguistic, religious and cultural point of view. For example, Osman et al. [75] found that cultural sensitivity during intervention delivery ensured parents’ participation. Tailoring was done purely based on needs [57, 68] and gender [102, 103]. It was also highlighted in the articles that immigrant families as well as parents have unique and individual needs.

Effectiveness of the Parent Support Programmes

Findings from the RCT studies (n = 18) were promising. Parent support programmes were effective in reducing children’s externalising [23, 84, 85, 92] and internalising problems [85, 89], attention problems [23], depression symptoms [38, 92] and traumatic stress reactions [92] when compared to the control group. Children in the intervention group reported less family arguing [92] than those in the control group. Parent support programmes were reported to improve parenting practices and skills [44, 84, 85, 89], promote positive parenting [84, 85] and reduce negative discipline or harsh punishment [84, 88]. In addition, improvements were seen in parent–child-relationship quality [88], problem-solving communication [38] and family functioning [88]. Parent support programmes have a great potential to reduce immigration-related stress [36], improve parental mental health and sense of competence in parenting [87]. One of the RCT studies did however report no effects on maternal mental distress, although the results here may have been due to the low levels of mental distress in the intervention group mothers at baseline [83].

Many of the programmes were targeted solely at families from migrant backgrounds, however, one study examined whether different target groups (migrant or non-migrant background) would benefit differently from the parent support programme. They found that migrants and non-migrants benefited equally from the parent support programme. They also found that only psychological problems in early childhood proved to be relevant in the prediction of psychological problems in adolescence, not migrant background or social status itself. [64] The investigation was conducted in Germany with 70 families with migrant backgrounds and 291 families without migrant backgrounds as a longitudinal study, where the assessments were conducted in early childhood (mean age of the children 4.2 years) and then again 10 years later in adolescence [64]. This finding highlights the importance of supporting migrant families at an early stage, since the migration event itself does not automatically mean psychological problems in children from migrant backgrounds.

Engagement, Satisfaction and Acceptability of the Parent Support Programmes

Studies that reported on the effects of parent support programmes and which conducted some measurements on feasibility, were reported to have high retention rates and satisfaction which can be seen as indicating a level of programme feasibility [85, 92]. Suggestions on how to improve feasibility from the intervention providers include giving participants more time for rehearsal and to adopt the new skills taught in the parent support programme [85].

Findings from the Qualitative Studies

The findings from the qualitative studies (data collected most often via focus group interviews) revealed that parents reported factors that improve participation as well as barriers to participation and challenges to carrying out the intervention. The factors that enhanced participation included motivation, incentives and trust [31]. Individual and family reasons, social reasons and fixed schedules were seen as barriers [31]. Also, parents may be more inclined to participate than adolescents [26]. Recognised challenges included the fit between intervention provider’ and parents’ expectations [73] or participants cultural background [74].

Qualitative studies reported parent perceived benefits. Parents reported positive consequences by increased positive parenting [71] and parenting competence [81], knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour [70]. Intervention targeting to fathers, increased their recognition and knowledge of mother’s depression [49]. Interventions also increased parents’ impression of positive feelings [82] and reduced loneliness and isolation [81]. One study reported that intervention increased parents’ capacity to attain education and employment [81]. Parents also recognised differences between their parenting skills and children’s’ behaviour [74] and mothers gained in terms of the ability to cope better [77].

The results of qualitative studies also revealed that interventions should be culturally sensitive and relevant [75, 80], should aim to improve parenting skills [80], communication skills [82] and that they need to include fathers in interventions if possible [49]. It was also noted that immigrant families should be viewed not in generalised terms but rather as individual units [76] and that their specific histories should be understood [42]. It is also important to listen to families [76, 78], but listening should be done carefully without the provocation of traumatic memories [78]. Also, families may have different goals in terms of the interventions [79]. Parents suggested that interventions should be delivered flexibly and include online options [72].

The role of facilitators was seen important, [68, 81] they should be respectful and collaborative [80] and know the culture and its’ values [76, 80]. Cultural tailoring and intercultural competence were thus seen as important [76].

Findings from the Mixed Methods Studies

Findings from the mixed methods studies were similar to those of the quantitative and qualitative studies. The methods used in the mixed methods studies were pre-test-post-test design combined with individual and focus group interviews [29, 35, 61, 98, 110], analysis of demographics or home visit records, telephone surveys and questionnaires [37, 54].

In mixed methods studies, parent support programmes were reported to improve family communication (between parents and between parent and child), relationships [35, 54, 61, 98, 106, 110] and social problem-solving skills in children [35]. Parents reported reductions in adolescent behavioural problems [35, 40]. The programmes were effective or perceived to be effective in improving the mental health of both parents and children [29, 106]. Shared experiences and listening to and supporting each other in parent support groups were seen as being of paramount importance here [61]. Parenting skills, practices, self-efficacy and confidence were improved or perceived to be higher after parent support programmes [54, 61, 98, 110]. One study however reported that the parent support programme had no effect on children’s aggression [35].

Findings from the Literature Reviews

The data search revealed only two literature reviews [4, 65]. One explored the barriers that immigrant families with children on the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) face, describing the parent support programmes used to address the barriers [65]. The other explored interventions targeted at traumatised immigrants and refugees [4].

The barriers that immigrant families with a child with ASD faced included, delayed diagnosis, difficulties in accessing services and cultural beliefs about child development. The article also presents a programme that is specifically targeted at immigrants with a child with ASD. The article included 21 articles, however, the detailed methods remained unreported [65].

The second review reported included six studies of which four reported findings from school-based interventions (targeted solely at children and adolescents) while two reported family support programmes, both of which were included in this review [93, 109]. The focus of the review by Slobodin et al. [4] was slightly different than ours since they also included studies that provided interventions in respect of children and adolescents without an intervention component relating to parents. They concluded that there is a shortage of research in this area and that is why firm conclusions cannot be made [4].

Findings from the Quasi-Experimental, Cross-Sectional, Feasibility and Pilot Studies

The results from non-RCT quantitative studies were promising however, as expected, many of them (n = 8/13) had small sample sizes ranging from 14 to 50 parents [47, 48, 50, 99, 105, 107, 108, 112]. These small but promising studies found that parent support programmes increased family functioning and reduced child behavioural problems reported by mothers [50]. Children reported better psychological functioning, acceptance and parenting warmth after the parent support programme [50]. Parents showed empathy towards their children and gained knowledge of the alternatives to corporal punishment after taking part to the parent support programme [112]. Kindergarten children whose families took part in the Migrant Education Even Start (MEES) programme performed better in English language measures in two follow-up measurement points than the children in the control group [47, 48]. Parent support programmes had high satisfaction and engagement rates and were seen as feasible even in fragile populations or contexts and also as urgently needed [62, 105, 107]. One small pilot study reported that cultural tailoring with a facilitator from the target population’s culture was time consuming and that they faced challenges in programme implementation particularly in respect of drop-out rates [99].

In five (n = 5/13) quantitative studies the sample ranged from 85 to 408 parents [46, 62, 100, 104, 109]. Parent support programmes were found to decrease parenting stress, loneliness, and isolation [100]. By taking part in the parent support programme, parents were encouraged to find and receive social, spousal and informational support and as well as learning a number of coping strategies [100]. Those families who valued shaming in child-rearing or who were dealing with the child protection system were however less likely to perceive the parent training to be acceptable [104]. The reasons as to why drop-outs occurred from the parent support programmes included family problems or sickness in the family, travel, change in life circumstances (for example leaving the country or starting work), lack of interest, and programme burden [62]. To successfully implement a parent support programme, its content need to be interesting to the participants while the provider must have a high level of competence in leading the programme. Negative characteristics in terms of programme implementation included the deemed unsuitability of the place where the sessions were being held (for example relating to the need to travel, or not familiar/felt safe, noise, materials needed not available), too complex content or homework and too lengthy sessions [62]. Monetary compensation and providing food were seen as participation enablers. The perceived benefits of the programme included, for example, changes in social and communicational skills, resilience and wellbeing [62]. One of the studies concentrated on parents’ technological skills enabling them to help their children with their school work. The study found significant differences between the pre- and post-test in terms of parent’s technology skills and self-efficacy in helping their children [46].

The benefits of the diverse programmes reported in the included studies are summarised in Table 4.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe what is known about the parent support programmes that are targeted at families who are immigrants. We were primarily interested in the objectives of the programmes, their content, recruitment strategies and, ultimately, the findings in respect of these programmes.

The objectives of the interventions were to support, enhance and strengthen parenting and to improve our knowledge of positive parenting practices. Most interventions included components of positive parenting and family communication. Through improved communication, the aim was to reduce child behavioural problems or, more specifically for example, substance abuse in adolescents. A common feature of the programmes was also to provide social and peer support to families even though this was not the primary aim of the programme. Interventions were usually conducted through group-based methods. Groups provided the possibility for social integration. They also created a platform where experiences relating to the programme topics could be shared and discussions, generated by the programme topics which were often sensitive, relating to issues such as mental health, could be held in a safe environment.

On recruitment strategies, we found that the most often used recruitment strategy reported in the included studies were recruitment from the local immigrant communities and agencies/organisations. Studies reported that direct invitation with a bilingual approach and word-of-mouth invitations were considered effective [28, 36, 44, 62, 80, 84, 89, 101, 105,106,107]. Only one study reported using social media for recruitment [98] which could be one potential way to reach participants in the future programmes. In addition, respected and trusted community members were seen as important links between the parent support programme providers and the target participants [92].

Overall, the findings of the included studies, regardless of the design and methods, led same direction: the parent support programmes that were well planned, structured and organised were viewed as beneficial to parents and children. Both –quantitative and qualitative– results of this review indicated that the programmes had a positive influence on overall child, parent and family wellbeing as well as on parenting skills and practices. This is worth noting, since parental wellbeing is associated with children’s wellbeing [113,114,115] and parental mental health problems are associated with the increased use of paediatric health care services [114]. It is profitable to invest in evidence-based preventive actions, such as parent support programmes that are proven to be effective.

As the present scoping review presents, the evidence-base regarding the effective parent support programmes targeted at families who are immigrants is still being assembled, we already have the results of a systematic review, a meta-analysis and meta-regression studies suggesting that extensive cultural adaptation is not necessary for the successful transportation of evidence-based parent support programmes [116, 117]. We have also learned from a recent study that a group-based parent support programme which is used worldwide, incredible years, had similar effects on child behavioural problems regardless of the family ethnic minority status [118]. These results suggest that when selecting the parent support programme for families who are immigrants, it may be more important to choose a well-studied intervention, with evidence of effectiveness, than to create resource consuming cultural adaptation actions [116,117,118]. This is however somewhat contradictory to our results, since many articles specifically emphasised the importance of need-based and culturally relevant programmes. Our explanation for this is that the need-based approach and culturally adapted programmes are important in terms of recruiting, engaging and acceptance of the programmes, even though the programme’s ultimate effectiveness relates to its well-structured and evidence-based content. Based on our findings, identifying the needs of the target group and cultural tailoring were highly important in terms of programme acceptability and results.

The cultural tailoring element was an important part of the interventions because cultural sensitivity and use of one’s own language ensured participation. It was also seen as important to understand the immigrant families’ background and that is why facilitators should understand the culture. In addition, religion is an important part of many cultures [119] and, as such, it is crucial to understand the culture also from this perspective, as religion can influence peoples’ actions and reactions, for example help-seeking or receiving help [120] or even parenting [121]. Nevertheless, the definitions and descriptions in respect of cultural tailoring remained either unclear or overly narrow in most of these studies.

We would therefore like to suggest that cultural tailoring should be seen as a bi-directional process including cultural tailoring from the perspective of immigrants’ cultural background, but also information about new host country’s cultural manners and procedures. This kind of cultural tailoring and social integration should be based on evidence-based interventions. As presented in the evidence-based Ladnaan -programme [75, 86, 87], the programme included information about the host-country’s society, the social- and health care systems and legislation in the regulated intervention, as it was deemed important to improve the knowledge of immigrant parents from this perspective. This may help them to understand better, why particular things are done as they are done, e.g. child protection actions and how the legislation of their new country deals with physical discipline. Increasing awareness of the fact that the physical punishment of children is prohibited by law, it may be possible to prevent harsh discipline and physical conflicts within the family. The preventive perspective is worth noting, since youth violence is also lower in countries with a complete ban on corporal punishment [122]. Parents do however need skills in terms of understanding alternative approaches to corporal punishment in dealing with challenging situations with their children.

All in all, the uncertainty in balancing between using a structured and highly regulated intervention and need-based and cultural tailoring, clearly demands that this area requires further investigation in terms of programmes targeted at immigrant families. Additionally, one other thing also caught our attention: The majority of the studies were conducted in North America with Latin American populations. Considering the European migrant crisis which began in 2014–2015 [123], the number of studies conducted in Europe was quite low. Also, there were only one study reporting a parent support program in initial registration centre [78] and of specific age groups, programs targeted to families with small children were limited. In the future, it would perhaps also be relevant to investigate how digitalisation and technology could be better utilised in parent support programmes.

Strengths and Limitations

It must be noted that these findings are summarised from different parent support programmes with heterogenous participants and thus that the findings reported here should be interpreted with caution. In addition, a quality appraisal of these studies has not been conducted in the context of the present study, although this is something that is not generally considered necessary in scoping reviews [18].

The study selection and data charting were conducted by two independent reviewers which is considered to strengthen the methodological quality of the current study. We did not have any time or language restrictions in our search strategy and we also covered the ‘grey’ literature from OpenGray, thus minimising the risk of publication bias. We did use a language translator with the German language articles. Articles in other languages (Spanish, Dutch, French. see Fig. 1) were not available as full-texts, so they were excluded at the full-text phase. One of the studies published in German was the only study that were conducted at the initial registration centre [78] and thus might provide the context for arguments over the need to begin evidence-based parent support at the earliest phase possible. This previously mentioned article also highlights the importance of including studies in reviews with no language restrictions.

Conclusion

To conclude, parent support programmes for families who are immigrants are essential to promote better parental practices and families’ overall wellbeing. When planning parent support programmes for families who are immigrants there are many applicable and effective interventions to be exploited. Nevertheless, it is important to tailor interventions to be culturally sensitive for better recruitment rates, engagement and acceptance. This cultural tailoring should include the tailoring of linguistical needs as well as cultural manners, beliefs and traditions during the planning and implementation of an evidence-based intervention. Furthermore, it is important to share information about the social- and welfare system, legislation and policy of the new host country, because families –especially parents– who are immigrants, need this type of information and knowledge in order to better understand the actions of public officials. Interventions can be delivered in many ways; the most important thing is to consider the target population, their motives and needs in order to achieve the best results and benefits possible.

References

UNHCR 2001–2021. United Nations refugee agency. Figures at a glance. www.unhcr.org. Accessed 23 Mar 2021.

Ministry of Employment and Economy 2015. Maahanmuuttajien psyykkistä hyvinvointia ja mielenterveyttä edistävät tekijät ja palvelut. Systemaattinen tutkimuskatsaus. Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriön julkaisuja 40/2015. Accessed 23 Mar 2021.

Gee DG. Sensitive periods of emotion regulation: influences of parental care on frontoamygdala circuitry and plasticity. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2016;2016:87–110.

Slobodin O, de Jong JT. Family interventions in traumatized immigrants and refugees: a systematic review. Transcult Psychiatry. 2015;52:723–42.

Bustamante LHU, Cerqueira RO, Leclerc E, Brietzke E. Stress, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in migrants: a comprehensive review. Braz J Psychiatry. 2017;40:220–5.

Birchler KM. A call for parenting interventions for refugee mothers with children younger than 3 years. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:583–4.

Chen W, Hall BJ, Ling L, Renzaho AM. Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:218–29.

Lindert J, Ehrenstein OS, Priebe S, Mielck A, Brähler E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):246–57.

Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, Layne CM, Kim S, Steinberg AM, Ellis H, Birman D. Trauma history and psychopathology in war-affected refugee children referred for trauma-related mental health services in the United States. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25:682–90.

Kien C, Sommer I, Faustmann A, Gibson L, Schneider M, Krczal E, Jank R, Klerings I, Szelag M, Kerschner B, Brattstrom P, Gartlehner G. Prevalence of mental disorders in young refugees and asylum seekers in European countries: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28:1295–310.

Bronstein I, Montgomery P. Psychological distress in refugee children: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14:44–56.

Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, Rashid M, Ryder AG, Guzder J, Hassan G, Rousseau C, Pottie K. Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH): Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. CMAJ. 2011;183:E959–67.

Meyer SR, Steinhaus M, Bangirana C, Onyango-Mangen P, Stark L. The influence of caregiver depression on adolescent mental health outcomes: findings from refugee settlements in Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1566-x.

Kim SY, Schwartz SJ, Perreira KM, Juang LP. Culture’s influence on stressors, parental socialization, and developmental processes in the mental health of children of immigrants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:343–70.

Eruyar S, Maltby J, Vostanis P. Mental health problems of Syrian refugee children: the role of parental factors. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27:401–9.

Kagan S, Weissbourd BE. Putting families first: America’s family support movement and the challenge of change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1994.

Trivette CM, Dunst CJ. Community-based parent support programs. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDEV, editors. Tremblay RE, topic ed. Encyclopedia on early childhood development. 2014. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/parenting-skills/according-experts/community-based-parent-support-programs. Accessed 2 Oct 2019.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H. Scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer's manual, JBI. 2020. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12. Accessed 23 Mar 2021.

Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb SE, Dixon-Woods M, McCulloch P, Wyatt JC, Chan AW, Michie S. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups. 2019. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 31 Oct 2019.

Lucas PJ, Baird J, Arai L, Law C, Roberts HM. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-7-4.

Annan J, Sim A, Puffer ES, Salhi C, Betancourt TS. Improving mental health outcomes of Burmese migrant and displaced children in Thailand: a community-based randomized controlled trial of a parenting and family skills intervention. Prev Sci. 2017;18:793–803.

Dababnah S, Habayeb S, Bear BJ, Hussein D. Feasibility of a trauma-informed parent–teacher cooperative training program for Syrian refugee children with autism. Autism. 2019;23:1300–10.

Allen ML, Garcia-Huidobro D, Hurtado GA, Allen R, Davey CS, Forster JL, Hurtado M, Lopez-Petrovich K, Marczak M, Reynoso U, Trebs L, Veronica Svetaz M. Immigrant family skills-building to prevent tobacco use in Latino youth: study protocol for a community-based participatory randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:242–51. http://europepmc.org/article/MED/23253201. Accessed 23 Mar 2021.

Azziz-Baumgartner C, Wilson LL. Applying a model of program adaptation to the Familias Fuertes parent/adolescent educational intervention for Latino immigrant families in the rural south. South Online J Nurs Res. 2009;9:7–7. https://www.snrs.org/sites/default/files/SOJNR/2009/Vol09Num03Art07.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2021.

Bacallao ML, Smokowski PR. “Entre Dos Mundos” (between two worlds): bicultural skills training with Latino immigrant families. J Prim Prev. 2005;26:485–509.

Bernhard JK. From theory to practice: Engaging immigrant parents in their children’s education. Alta J Educ Res. 2010;56:319–34.

Cowell JM, McNaughton DB, Ailey S. Development and evaluation of a Mexican immigrant family support program. J Sch Nurs (Allen Press). 2000;16:32–9.

Dumka LE, Mauricio AM, Gonzales NA. Research partnerships with schools to implement prevention programs for Mexican origin families. J Prim Prev. 2007;28:403–20.

Garcia-Huidobro D, Allen M, Rosas-Lee M, Maldonado F, Gutierrez L, Svetaz MV, Wieling E. Understanding attendance in a community-based parenting intervention for immigrant Latino families. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17:57–69.

Gonzalez LM, Borders LD, Hines EM, Villalba JA, Henderson A. Parental involvement in children’s education: considerations for school counselors working with Latino immigrant families. Prof Sch Couns. 2013;16:185–93.

Gonzalez LM. A college knowledge outreach program for Latino immigrant parents: process and evaluation. J Soc Action Couns Psychol. 2017;9:38–54.

Hendrickson SG, Williams J, Acee TW. Immigrant Hispanic mothers’ participation in a dual-site safety intervention. Hisp Health Care INT. 2008;6:71–9.

Knox L, Guerra NG, Williams KR, Toro R. Preventing children’s aggression in immigrant Latino families: a mixed methods evaluation of the families and schools together program. Am J Community Psychol. 2011;48:65–76.

López-Zerón G, Parra-Cardona JR, Yeh H. Addressing immigration-related stress in a culturally adapted parenting intervention for mexican-origin immigrants: initial positive effects and key areas of improvement. Fam Process. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12481.

McNaughton DB, Hindin P, Guerrero Y. Directions for refining a school nursing intervention for Mexican immigrant families. J Sch Nurs (Allen Press). 2010;26:430–5.

McNaughton DB, Cowell JM, Fogg L. Efficacy of a Latino mother-child communication intervention in elementary schools. J Sch Nurs. 2015;31:126–34.

McNaughton DB, Cowell JM, Fogg L. Adaptation and feasibility of a communication intervention for Mexican immigrant mothers and children in a school setting. J Sch Nurs (ALLEN PRESS). 2014;30:103–13.

Pantin H, Coatsworth JD, Feaster DJ, Newman FL, Briones E, Prado G, Schwartz SJ, Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: the efficacy of an intervention to promote parental investment in Hispanic immigrant families. Prev Sci. 2003;4:189–201.

Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Coatsworth JD, Szapocznik J. Preventing substance abuse in Hispanic immigrant adolescents: an ecodevelopmental, parent-centered approach. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2003;25:469–500.

Paris R. “For the dream of being here, one sacrifices…”: voices of immigrant mothers in a home visiting program. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78:141–51.

Parra-Cardona JR. Healing through parenting: an intervention delivery and process of change model developed with low-income latina/o immigrant families. Fam Process. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12429.

Parra-Cardona J, Bybee D, Sullivan CM, Dates B, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Tams L, Bernal G. Examining the impact of differential cultural adaptation with Latina/o immigrants exposed to adapted parent training interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85:58–71.

Parra-Cardona J, López-Zerón G, Villa M, Zamudio E, Escobar-Chew A, Rodríguez MMD. Enhancing parenting practices with Latino/a immigrants: Integrating evidence-based knowledge and culture according to the voices of Latino/a parents. Clin Soc Work J. 2017;45:88–98.

Rivera H. Studying the impact of technology-infused activities among low-income Spanish-speaking immigrant families. J Lat Educ. 2014;13:196–211.

St. Clair L, Jackson B. Effect of family involvement training on the language skills of young elementary children from migrant families. Sch Community J. 2006;16:31–42.

St Clair L, Jackson B, Zweiback R. Six years later: effect of family involvement training on the language skills of children from migrant families. Sch Community J. 2012;22:9–19.

Valdez CR, Martinez E. Mexican immigrant fathers’ recognition of and coping with maternal depression: the influence of meaning-making on marital and co-parenting roles among men participating in a family intervention. J Lat Psychol. 2019;7:304–21.

Valdez CR, Padilla B, Moore SM, Magana S. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes of the Fortalezas Familiares intervention for Latino families facing maternal depression. Fam Process. 2013;52:394–410.

Valdez CR, Abegglen J, Hauser CT. Fortalezas familiares program: building sociocultural and family strengths in latina women with depression and their families. Fam Process. 2013;52:378–93.

Parra Cardona J, Holtrop K, Cordova D Jr, Escobar-Chew AR, Horsford S, Tams L, Villaruel FA, Villalobos G, Dates B, Anthony JC, Fitzgerald HE. “Queremos aprender”: Latino immigrants’ call to integrate cultural adaptation with best practice knowledge in a parenting intervention. Fam Process. 2009;48:211–31.

Parra Cardona JR, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Forgatch M, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Holtrop K, Escobar-Chew AR, Tams L, Dates B, Bernal G. Culturally adapting an evidence-based parenting intervention for Latino immigrants: the need to integrate fidelity and cultural relevance. Fam Process. 2012;51:56–72.

Cwikel J, Segal-Engelchin D, Niego L. Addressing the needs of new mothers in a multi-cultural setting: an evaluation of home visiting support for new mothers—mom to mom (Negev). Psychol Health Med. 2018;23:517–24.

Friedrich L, Smolka A. Concepts and effects of parent education programs for supporting early childhood education in immigrant families. Zeitschrifte Fur Familienforschung-Journal of Family Research. 2012;24:178–98.

German M. Educational psychologists promoting the emotional wellbeing and resilience of refugee parents. Educ Child Psychol. 2008;25:91–103.

Guo K, Gray J. The exercising of relational agency in parenting for newly arrived families in supported playgroups. Commun Child Fam Aust. 2017;11:33–48.

Leijten P, Raaijmakers MAJ, Orobio DC, Matthys W. Ethnic differences in problem perception: immigrant mothers in a parenting intervention to reduce disruptive child behavior. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:323–31.

Measham T, Guzder J, Rousseau C, Pacione L, Blais-McPherson M, Nadeau L. Refugee children and their families: supporting psychological well-being and positive adaptation following migration. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44:208–15.

NCT02829086. Evaluation of the refugee family strengthening (RFS) Program. 2016. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02829086. Accessed 23 Mar 2021.

Nieuwboer C, van’t Rood R. Learning language that matters: a pedagogical method to support migrant mothers without formal education experience in their social integration in Western countries. Int J Intercult Relat. 2016;51:29–40.

Ponguta LA, Issa G, Aoudeh L, Maalouf C, Nourallah S, Khoshnood K, Zonderman AL, Katsovich L, Moore C, Salah R, Al-Soleiti M, Britto PR, Leckman JF. Implementation evaluation of the mother-child education program among refugee and other vulnerable communities in Lebanon. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2019;2019:91–116.

Samarasinghe KL. A conceptual model facilitating the transition of involuntary migrant families. ISRN Nurs. 2011. https://doi.org/10.5402/2011/824209.

Schulz W, Bothe T, Hahlweg K. Prävention psychischer Probleme und Verhaltensauffälligkeiten von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund und deren Müttern: Ergebnisse eines 10-Jahres-Follow-up = Prevention of psychological disorders and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with migration background and their mothers: results of a 10-year follow-up. Verhaltenstherapie. 2018;28:82–92.

Sritharan B, Koola MM. Barriers faced by immigrant families of children with autism: a program to address the challenges. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;39:53–7.

Van den Berg M. ‘Activating’ those that ‘lag behind’: space-time politics in Dutch parenting training for migrants. Patterns Prejud. 2016;50:21–37.

van Es CM, Mooren T, Zwaanswijk M, te Brake H, Boelen PA. Family empowerment (FAME): study protocol for a pilot implementation and evaluation of a preventive multi-family programme for asylum-seeker families. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2019;5:1–9.

Warr D, Mann R, Forbes D, Turner C. Once you’ve built some trust: using playgroups to promote children’s health and wellbeing for families from migrant backgrounds. Australas J Early Child. 2013;38:41–8.

Weine SM. Developing preventive mental health interventions for refugee families in resettlement. Fam Process. 2011;50:410–30.

Yuen LH. New immigrant parents’ experiences in a parent education programme. Int J Early Years Educ. 2019;27:20–33.

Ballard J, Wieling E, Forgatch M. Feasibility of implementation of a parenting intervention with Karen refugees resettled from Burma. J Marital Fam Ther. 2018;44:220–34.

Dababnah S, Habayeb S, Baker B, Hussein D. Feasibility of a behavior management training program for Syrian refugee caregivers of children with autism. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018;31:581–2.

Kim E, Choe HS, Webster-Stratton C, Kim E, Choe HS, Webster-Stratton C. Korean immigrant parents’ evaluation of the delivery of a parenting program for cultural and linguistic appropriateness and usefulness. Fam Community Health. 2010;33:262–74.

Kim E, Hong S, Rockett CM. Korean American parents’ perceptions of effective parenting strategies in the United States. J Cult Divers. 2016;23:12–20.

Osman F, Flacking R, Klingberg Allvin M, Schön U, Schön U. Qualitative study showed that a culturally tailored parenting programme improved the confidence and skills of Somali immigrants. Acta Paediatr. 2019;108:1482–90.

Sarimski K. Wahrnehmung einer drohenden geistigen Behinderung und Einstellungen zur Frühförderung bei Eltern mit türkischem Migrationshintergrund = Attitudes toward intellectual disabilities and early intervention in parents with Turkish migrant background. Frühförderung interdisziplinär. 2013;32:3–16.

Schnur E, Koffler R, Wimpenny N, Giller H. Family child care and new immigrants: cultural bridge and support. Child Welf. 1995;74:1237–48.

Schweitzer J, Schliessler C, Kohl RM, Nikendei C, Oitzen B. Systemische Notfall beratung mit geflüchteten Familien in einer Erstregistrierungsstelle = Systemic emergency counselling for refugee families at an initial registration centre. Familiendynamik: Systemische Praxis und Forschung. 2019;44:144–54.

Singh S, Sylvia MR, Ridzi F. Exploring the literacy practices of refugee families enrolled in a book distribution program and an intergenerational family literacy program. Early Child Educ J. 2015;43:37–45.

Cardona JP, Holtrop K, Cordova D Jr, Escobar-Chew AR, Horsford S, Tams L, Villarruel FA, Villalobos G, Dates B, Anthony JC, Fitzgerald HE. “Queremos Aprender”: Latino immigrants’ call to integrate cultural adaptation with best practice knowledge in a parenting intervention. Fam Process. 2009;48:211–31.

Stewart M, Spitzer DL, Kushner KE, Shizha E, Letourneau N, Makwarimba E, Dennis C, Kariwo M, Makumbe K, Edey J. Supporting refugee parents of young children: “knowing you’re not alone.” Int J Migr Health Soc Care. 2018;14:15–29.

Wong YJ, Tran KK, Schwing AE, Cao LH, Phung-Hoang Ho P, Nguyen Q-T. Vietnamese american immigrant parents: a pilot parenting intervention. Fam J. 2011;19:314–21.

Bjørknes R, Larsen M, Gwanzura-Ottemöller F, Kjøbli J. Exploring mental distress among immigrant mothers participating in parent training. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;51:10–7.

Bjorknes R, Manger T. Can parent training alter parent practice and reduce conduct problems in ethnic minority children? A randomized controlled trial. Prev Sci. 2013;14:52–63.

Lau AS, Fung JJ, Ho LY, Liu LL, Gudino OG. Parent training with high-risk immigrant Chinese families: a pilot group randomized trial yielding practice-based evidence. Behav Ther. 2011;42:413–26.

Osman F, Flacking R, Schön U, Klingberg-Allvin M. A support program for somali-born parents on children’s behavioral problems. Pediatrics. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2764.

Osman F, Salari R, Klingberg-Allvin M, Schon UK, Flacking R. Effects of a culturally tailored parenting support programme in Somali-born parents’ mental health and sense of competence in parenting: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017600.

Puffer ES, Annan J, Sim AL, Salhi C, Betancourt TS. The impact of a family skills training intervention among Burmese migrant families in Thailand: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:1–19.

Williamson AA, Knox L, Guerra NG, Williams KR. A pilot randomized trial of community-based parent training for immigrant Latina mothers. Am J Community Psychol. 2014;53:47–59.

Wong JJ, Roubinov DS, Gonzales NA, Dumka LE, Millsap RE. Father enrollment and participation in a parenting intervention: personal and contextual predictors. Fam Process. 2013;52:440–54.

Yagmur S, Mesman J, Malda M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Ekmekci H. Video-feedback intervention increases sensitive parenting in ethnic minority mothers: a randomized control trial. Attach Hum Dev. 2014;16:371–86.

Betancourt TS, Berent JM, Freeman J, Frounfelker RL, Brennan RT, Abdi S, Maalim A, Abdi A, Mishra T, Gautam B, Creswell JW, Beardslee WR. Family-based mental health promotion for Somali bantu and Bhutanese refugees: feasibility and acceptability trial. J Adolesc Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.08.023.

Weine S, Kulauzovic Y, Klebic A, Besic S, Mujagic A, Muzurovic J, Spahovic D, Sclove S, Pavkovic I, Feetham S, Rolland J. Evaluating a multiple-family group access intervention for refugees with PTSD. J Marital Fam Ther. 2008;34:149–64.

Javier JR, Reyes A, Coffey DM, Schrager SM, Samson A, Palinkas L, Kipke MD, Miranda J. Recruiting Filipino immigrants in a randomized controlled trial promoting enrollment in an evidence-based parenting intervention. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21:324–31.

Lau AS, Fung JJ, Yung V. Group parent training with immigrant Chinese families: enhancing engagement and augmenting skills training. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:880–94.

Pejic V, Hess RS, Miller GE, Wille A. Family first: community-based supports for refugees. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86:409–14.

Pejic V, Alvarado AE, Hess RS, Groark S. Community-based interventions with refugee families using a family systems approach. Fam J Alex Va. 2017;25:101–8.

Garcia-Huidobro D, Diaspro-Higuera M, Palma D, Palma R, Ortega L, Shlafer R, Wieling E, Piehler T, August G, Svetaz MV, Borowsky IW, Allen ML. Adaptive recruitment and parenting interventions for immigrant Latino families with adolescents. Prev Sci. 2019;20:56–67.

Nagoshi J, Nagoshi C, Small E, Okumu M, Marsiglia FF, Dustman P, Than K. Families preparing a new generation: adaptation of an adolescent substance use intervention for Burmese refugee families. J Soc Soc Work Res. 2018;9:615–35.

Stewart M, Makwarimba E, Letourneau NL, Kushner KE, Spitzer DL, Dennis C, Shizha E. Impacts of a support intervention for Zimbabwean and Sudanese refugee parents: “I am not alone.” Can J Nurs Res. 2015;47:113–40.

Weine S, Knafl K, Feetham S, Kulauzovic Y, Klebic A, Sclove S, Besic S, Mujagic A, Muzurovic J, Spahovic D. A mixed methods study of refugee families engaging in multiple-family groups. Fam Relat. 2005;54:558–68.

ISRCTN22321773. Helping refugee parents thrive: an evaluation of the caregiver support intervention with Syrian refugees in Lebanon. 2019. http://www.whoint/trialsearch/Trial2aspx?TrialID=ISRCTN22321773.

ISRCTN33665023. Helping refugee parents thrive: assessing the readiness of the caregiver support intervention for a fully powered evaluation with Syrian refugees in Lebanon. 2019. http://www.whoint/trialsearch/Trial2aspx?TrialID=ISRCTN33665023.

Ho J, Yeh M, McCabe K, Lau A. Perceptions of the acceptability of parent training among Chinese immigrant parents: contributions of cultural factors and clinical need. Behav Ther. 2012;43:436–49.

Cardona JRP, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Forgatch M, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Holtrop K, Escobar-Chew AR, Tams L, Dates B, Bernal G. Culturally adapting an evidence-based parenting intervention for Latino immigrants: the need to integrate fidelity and cultural relevance. Fam Process. 2012;51:56–72.

Wu T, Lee J. A pilot program to promote mental health among Asian-American immigrant children and their parents: a community-based participatory approach. Int J Child Youth Fam Stud. 2015;6:730–45.

Ying Y. Strengthening intergenerational/intercultural ties in immigrant families (SITIF): testing a culturally-sensitive, community-based intervention with Chinese American parents. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2007;5:65–88.

Ying Y. Strengthening intergenerational/intercultural ties in migrant families: a new intervention for parents. J Community Psychol. 1999;27:89–96.

Weine SM, Raina D, Zhubi M, Delesi M, Huseni D, Feetham S, Kulauzovic Y, Mermelstein R, Campbell RT, Rolland J, Pavkovic I. The TAFES multi-family group intervention for Kosovar refugees: a feasibility study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:100–7.

Umubyeyi B, Harris G. Promoting non-violent parenting among refugee mothers in Durban. Soc Work-Maatskaplike Werk. 2012;48:456–66.

Allen ML, Garcia-Huidobro D, Hurtado GA, Allen R, Davey CS, Forster JL, Hurtado M, Lopez-Petrovich K, Marczak M, Reynoso U, Trebs L, Svetaz MV. Immigrant family skills-building to prevent tobacco use in Latino youth: study protocol for a community-based participatory randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-242.

Renzaho AMN, Vignjevic S. The impact of a parenting intervention in Australia among migrants and refugees from Liberia, Sierra Leone, Congo, and Burundi: results from the African migrant parenting program. J Fam Stud. 2011;17:71–9.

Bennett AC, Brewer KC, Rankin KM. The association of child mental health conditions and parent mental health status among U.S. Children, 2007. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1266–75.

Lavigne JV, Meyers KM. Meta-analysis: association of parent and child mental health with pediatric health care utilization. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019;44:1097–110.

Jeong J, Li Z. The association between fathers’ depression and children’s socioemotional development: evidence from a longitudinal household survey in China. Prev Sci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01117-3.

Gardner F, Montgomery P, Knerr W. Transporting evidence-based parenting programs for child problem behavior (age 3–10) between countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45:749–62.

Leijten P, Melendez-Torres GJ, Knerr W, Gardner F. Transported versus homegrown parenting interventions for reducing disruptive child behavior: a multilevel meta-regression study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:610–7.

Gardner F, Leijten P, Harris V, Mann J, Hutchings J, Beecham J, Bonin EM, Berry V, McGilloway S, Gaspar M, Joao Seabra-Santos M, Orobio de Castro B, Menting A, Williams M, Axberg U, Morch WT, Scott S, Landau S. Equity effects of parenting interventions for child conduct problems: a pan-European individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:518–27.

Hodge DR. Spiritual assessment with refugees and other migrant populations: a necessary foundation for successful clinical practice. J Relig Spiritual Soc Work: Soc Thought. 2019;38:121–39.

Planey AM, Smith SM, Moore S, Walker TD. Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking among African American youth and their families: a systematic review study. Chil Youth Serv Rev. 2019;101:190–200.

Petro MR, Rich EG, Erasmus C, Roman NV. The effect of religion on parenting in order to guide parents in the way they parent: a systematic review. J Spiritual Ment Health. 2018;20:114–39.

Elgar FJ, Donnelly PD, Michaelson V, Gariépy G, Riehm KE, Walsh SD, Pickett W. Corporal punishment bans and physical fighting in adolescents: an ecological study of 88 countries. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

European council: EU migration policy. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/migratory-pressures/. Accessed 15 May 2020.

NCT03040154: Engaging Immigrants in Preventive Parenting Interventions. (2017). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03040154.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the information specialist Anna Tiitinen for preparing the search strategies for the current review. We gratefully also thank Heidi Parisod and Arja Holopainen from the Finnish Nursing Research Foundation for coming up with the initial idea for the review. And finally, we gratefully acknowledge Itla, the Children's Foundation for their financial support of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamari, L., Konttila, J., Merikukka, M. et al. Parent Support Programmes for Families Who are Immigrants: A Scoping Review. J Immigrant Minority Health 24, 506–525 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01181-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01181-z