Abstract

Recent literature suggests that people increase their life satisfaction over time as a result of developing positive psychological resources (e.g. benefit finding). However, this hypothesis has not yet tested in children. Since suffering from illness is usually associated with challenge and growth, we hypothesized that changes in life satisfaction in a sample of ill children would depend on to what extent they developed resources. Children with a life threatening illness (N = 67 at T1 and N = 49 at T2, ages 7–18 years) completed the Student Life Satisfaction Scale, a measure of health-related functioning problems, a measure of positive emotions (PE), the Benefit Finding Scale for Children, and a measure of strengths from the Values in Action Inventory of Character Strengths for Youth. The same measures were assessed 6 months after the first assessment. Using structural equation modeling techniques, results revealed that health-related functioning problems were associated with negative changes in life satisfaction over time. Moreover, increases in benefit finding and character strengths (i.e., love and gratitude) predicted positive changes in LS over time. Finally, PE predicted changes in benefit finding over time through several personal strengths (i.e., vitality and gratitude). The development of positive psychological resources in children experiencing high levels of stress may promote desirable psychological outcomes. Therefore, in order to help clinicians prevent negative outcomes, future research should strive to better understand life satisfaction and its underlying predictors in children experiencing difficult life circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Traditional assessments of children’s mental health in the context of chronic illness have focused on measuring distressing experiences and symptoms of psychopathology (Bennett 1993; Collins et al. 2000; Hedstrom et al. 2003). However, there is growing interest in assessing and promoting well-being, particularly now that survival rates are increasing and medical treatments have advanced significantly (Zebrack and Chesler 2002; Klassen et al. 2011; Hedström et al. 2004; Huebner et al. 2004).

Life satisfaction (LS) has been defined as an individual’s perception of the quality of his or her life as a whole or within specific life domains (e.g., family life, school experiences) (Diener et al. 1999; Huebner et al. 2005). Although research about LS in children and adolescents is relatively scarce compared with research pertaining to adults, it has recently become common for pediatric studies to incorporate these measures. This change reflects a growing awareness that well-being goes beyond the mere absence of symptoms (Huebner et al. 2005; Greenspoon and Saklofske 2001).

Research on children has revealed a wide array of correlates of LS, including a variety of psychopathological symptoms (depression, anxiety, low self-efficacy, loneliness) and physical health indices (e.g., eating behavior, exercise) (Huebner et al. 2005).

With regard to predictors of LS in children with a life threatening illness, health-related quality of life plays an important role. Illness during childhood and adolescence is connected with a wide range of negative experiences such as fears of alienation, fears of altered appearance, fears of dying and various physical concerns (Hedstrom et al. 2003). Furthermore, symptoms often associated with treatment and other long-term consequences of illness (e.g. chronic fatigue or pain negatively) often negatively impact overall quality of life (Zebrack and Chesler 2002; Whitaker et al. 2013).

Existing research on the contribution of psychological resources toward increased LS over time is fairly limited. Previous studies suggest that people increase their LS over time not only from the summation of good and bad feelings, but also as a result of the development of resources for better living (Cohn et al. 2009). These skills include resilience, emotion regulation, problem solving, and the ability to change perspective (Cohn et al. 2009). Consistent with this model, this study explores whether certain psychological resources previously shown to be associated with positive adjustment (i.e. benefit finding and personal strengths) also promote increased LS over time in children with a life threatening illness.

Regarding benefit finding (BF),Footnote 1 over the last couple of decades there has been increasing evidence suggesting that although a minority of children has some difficulties with adjustment and/or symptoms of psychological distress, the majority with a medical condition or a chronic illness also experience positive changes and growth (Canning et al. 1992; Currier et al. 2009; Phipps et al. 2007). Research on the construct of BF is particularly relevant for children with a life threatening illness given the different pathways by which BF may improve physical and psychological health (Bower et al. 2009). Studies of the relationship between BF and other positively-valenced outcomes among children and adolescents with a life threatening illness largely suggest that a positive relationship exists between these variables (Meyerson et al. 2011). However, some studies did not find a relationship between reported growth and adjustment (Calhoun et al. 2010). These inconsistent results suggest that this relationship may be more complex than previously believed. In their review, Helgeson et al. (2006) suggested that BF was more likely to be associated with other positive outcomes when more time had elapsed since the traumatic event, highlighting the potential utility of perceived benefits to serve as catalyst for long-term change beyond itself. Alternatively, third variables may be moderating this relationship. For example, Triplett et al. (2012) found that reported growth had a significant but weak association with LS. When they tested the indirect path through meaning in life by which reported growth is linked to LS, this path was also statistically significant.

Personal strengths may help to explain these relationships. Research on character strengths has shown that personal strengths play an important role in adjustment during heightened levels of stress (Peterson and Seligman 2003; Peterson et al. 2006). Some studies have suggested that growth following trauma may entail the strengthening of character (Peterson et al. 2008). In a study of changes in character before and after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Peterson and Seligman (2003) found that certain personal strengths, namely faith, hope, and love, increased among Americans. These findings suggest that psychological strengths and virtues may be context-dependent and especially sensitive to changes in life circumstances. Similarly, previous research on personal strengths has shown that people with serious physical illnesses report higher levels of appreciation of beauty, bravery, curiosity, fairness, forgiveness, gratitude, humor, kindness, love of learning, and spirituality (Peterson et al. 2006). Furthermore, some studies have indicated that changes in character strengths accompany, or even predict, the positive changes in LS over time (Peterson et al. 2006; Proyer et al. 2013). The role of personal strengths as predictors of subjective well-being has been also demonstrated in a sample of adolescents (Gillham et al. 2011).

Taken together, these studies suggest that LS may change amidst adversity and changes in health-related quality of life, and that BF and character strengths, among other mediators, may be partly responsible for changes in LS. Furthermore, these studies suggest that character strengths play an especially important role during heightened levels of stress. That being said, pathways by which children actually derive benefits from a difficult experience are still unclear.

Thus far, empirical studies have still paid little attention to emotional states as predictors of growth. However, some studies have found that resilient children are characterized by high positive emotionality (Block and Kremen 1996). There is a growing interest in providing empirical support for the role that positive emotions (PE) may have as important facilitators of adaptive coping and adjustment to chronic stress (e.g., Folkman and Moskowitz 2000). The occurrence of PE amidst adversity, whether in isolation or coexisting with negative emotions (Larsen et al. 2003), may provide the necessary psychological resources to help buffer the negative effects of stress and restore further coping efforts (Tugade and Fredrickson 2002). Joseph et al. (2012) modified their previous model of growth to include affective components (e.g., positive and negative affect) as predictors of growth. They suggested that emotional states occur as a repetitive and cyclic process until discrepancies between pre-trauma assumptive worldviews and post-trauma information are resolved.

The broaden-and-build theory of PE (Fredrickson 1998, 2001) provides a useful theoretical framework to understand how PE may promote BF. According to this theory, to the extent that PE broaden the scope of attention and cognition, and enable flexible thinking, PE should also enhance the enduring personal resources that are essential to adaptive coping responses following traumatic circumstances (Fredrickson et al. 2003) and that also can lead to personal growth, which will be the main focus of this research. Personal resources include physical (e.g. healthy behaviors) (Cohen et al. 2006), social (Kok et al. 2013), intellectual (Tugade and Fredrickson 2002), and psychological resources (e.g., optimism, creativity) (Scheier and Carver 1993). An individual’s character may change amidst adversity. It is likely that a change in character strengths often accompanies this building of resilience or is even partly responsible for its development (Peterson et al. 2006). In turn, as mentioned above, these growth experiences have a reciprocal effect and may entail the strengthening of character (Peterson et al. 2008). Therefore, although PE can be considered transient and ephemeral, they may have a long-term effect on increasing or maintaining people’s subsequent psychological well-being since they help foster more effective long-term coping resources (Tugade et al. 2004).

Currently, there are no studies that have considered the relationships among these specific variables and most of the studies that examine these dimensions have been conducted with adult samples (Peterson et al. 2006; Cohn et al. 2009; Fredrickson 2001). Another limitation of previous studies is that most of them are cross-sectional (Meyerson et al. 2011), which makes it difficult to shed light on the causal role of BF and character strengths in positive psychological changes during illness. In order to address some of the existing gaps in the existing literature on coping, we examined several factors that seem to be related to and/or influence BF among children and adolescents coping with a serious illness.

1.1 The Present Study

This paper will specifically focus on aspects of positive adjustment that children may exhibit across time when during a life threatening illness. Using path analysis through structural equation modeling (SEM) and a longitudinal design to explore the dynamics between variables, the present study aims to explore the role of health-related functioning problems, BF and personal strengths as predictors of changes in LS over time. It was hypothesized two different general pathways by which LS can change over time. First, following more traditional research, it was expected that LS would be negatively predicted by health-related functioning problems. Second, based on more recent literature on positive mental health, it was expected that LS would be positively predicted by changes in both personal strengths and BF. Finally, it was hypothesized that personal strengths may mediate the relationship between PE and changes in BF over time.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

Forty-nine children (59 % male) with a severe illness participated in this study. Participants ranged from 7 to 18 years of age (mean = 12.06; SD = 3.31 years). In terms of pathology, 69.4 % of participants were diagnosed with cancer, 10.2 % had undergone or were about to undergo organ transplantation and 20.4 % suffered from other life-threatening diseases. Regarding the stage of the disease, the percentages were distributed as follows: 34.5 % were off of treatment, 48.3 % in active treatment, and 17.2 % in relapse. Mean months since diagnosis was 53.74 (SD = 68.34). The mean severity of the disease, which was assessed by doctors on a scale from 0 to 10, was 6.26 out of 10 (SD = 2.90). Regarding the prognosis reported by doctors, the percentages were distributed as follows: 14.3 % unfavorable, 17.9 % favorable and 69.6 % intermediate risk. The average probability of survival at 1 and 5 years were 83.39 and 69.61 %, respectively.

2.2 Measures

-

(a)

General LS. The Student Life Satisfaction Scale, SLSS (Huebner 1991) consists of seven items designed to measure overall satisfaction with life, without making any specific reference to any particular domain (e.g., “In my life things are going well”). Each item is answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “never” to 3 = “almost always”. In our study, internal consistency was α =.78.

-

(b)

Positive emotions. The Positive and Negative Emotional Style Scale, PNES (Cohen et al. 2006) contains twelve adjectives (six positive and six negative). It was complemented with ten additional positive adjectives to cover a wider spectrum of emotional relevant responses (e.g., grateful, safe, hopeful) and four negative adjectives related to loneliness and tiredness (Pressman and Cohen 2012). Children were asked to what extent (0 = “nothing” to 4 = “extremely”) they felt each emotion on the day of the assessment. In the current sample, both the PE scale (α = .92) and the NE scale (α = .87) showed strong internal consistency.

-

(c)

Benefit finding. The Benefit Finding Scale for Children, BFSC (Phipps et al. 2007) includes 10 items (e.g. “Having had my illness has helped me become a stronger person”) depicting potential benefits of the illness rated on 5-point Likert scales (1 = “not true at all” to 5 = “very true for me”). In this study, the level of internal consistency was α = .90.

-

(d)

Personal strengths. The Values in Action Inventory of Character Strengths for Youth, VIA-Y (Park and Peterson 2006) is a 198-item scale that allows for the evaluation of 24 personal strengths. In order to keep the protocol as short as possible, we selected strengths (i.e., love, vitality, and gratitude) that have shown the highest correlations with LS in a large sample of children (N = 1200) with similar demographic characteristics (Gimenez 2010). The resulting scale contained 25 items. The highest-loading items on each scale were used. Each item is answered on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not true at all” to 5 = “very true for me”). Levels of internal consistency of subscales were α = .56, .84, and .73, respectively.

-

(e)

Health-related functioning problems. We used The Pediatric Quality of Life Scale, PedsQoL (Varni et al. 2002). The health-related questionnaire assesses how often in the past month children have had problems with pain, anxiety related to medical procedures and treatment, nausea, cognitive problems, concerns about the disease, physical appearance and communication with others about their disease. Items are presented on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 4 = “almost always”). In the present study Cronbach’s alpha was α = .86.

-

(f)

Medical status: To complement data on the children’s health status, we collected information from the main pediatric doctors who were treating the children at the hospital. Doctors were asked to complete a report form with information regarding the children’s diagnosis, severity (measured by a scale from 0 to 10), the stage of disease (i.e., active treatment/off treatment/relapse/palliative), and estimated probability of survival at 1 and 5 years.

2.3 Procedure

Children in the study were recruited from four public hospitals where they were hospitalized.Footnote 2 A total of 81 children (ranging in age from 7 to 18 years) were initially contacted. Participants who were unable to answer the provided questionnaires due to their cognitive development (n = 6), health status (n = 5) or who declined to participate (n = 3) in the study were excluded. For their inclusion, both parents and children had to agree to participate and sign an informed consent. Sixty-seven children completed self-report measures at the first assessment, T1. In order to ensure that children understood the scales’ response format to give the correct answer, we used different strategies. Firstly, a pre-test protocol was incorporated to determine the cognitive competence of participants and ensure that they understood Likert-format scales (Cummins and Lau 2005). When needed, children were trained in ordering magnitudes, scaling concrete objects, and scaling abstract references (i.e. emotion faces). Whenever children showed any problem with Likert-format scales, we used a reduced-choice format. Secondly, for some questionnaires (e.g. quality of life scales), we used age group versions (ages 5–7; ages 8–12; ages 13–18). They are parallel forms with minor differences in the test instructions and wording which are structured to be more appropriate for young children, children and teens. For instance, the young children version (ages 5–7) used a reduced-choice Likert-format scale and visual aids (i.e. faces). Thirdly, to maximize the children’s understanding of the multiple response options, we also used visual cards and thermometer images so that children could physically point to their answer if needed (Cummins and Lau 2005). The thermometer scale option has shown a good reliability for children below 9 years of age (Cremeens et al. 2007). Finally, instruments were administered verbally when needed.

At T2, 6–9 months after the first assessment, children were contacted again. Forty-nine participants (73 % of the initial sample, 57 % male) completed a second set of measurements of PE, personal strengths, and BF. The loss of participants at the time of our T2 follow-up was due to mortality (n = 5), health status (n = 8) and difficulties in making an appointment (n = 5). There were no significant differences in any of the main characteristics of the sample (i.e. age, gender, diagnosis, time since diagnosis, severity, and prognosis at 1 and 5 years) between those who did not complete the second measurement and those who completed (all p > 0.05).

2.4 Data Analysis

Descriptive and correlation analyses were initially conducted. Then, different path models were tested to assess which showed best fit, using path analysis through SEM.

The hypothesized structural equation models were tested using AMOS v18.0 (SPSS). The full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation method was used to generate the standardized parameter estimates. The following criteria (Hu and Bentler 1999; Yu 2002) were utilized: (a) χ 2: a perfect fit is indicated by a non-significant value; (b) χ 2/gl: a good fit is indicated by a value lower than 2; (c) CFI and TLI: an acceptable fit is indicated by a value ≥.90, whereas a good fit is indicated by a value ≥.95; (d) RMSEA: an acceptable fit is indicated by a RMSEA value ≤.08 (90 % CI ≤ 0.10), whereas a good fit is indicated by a RMSEA ≤ .05 (90 % CI ≤ 0.08); (e) AIC: is a comparative indicator, where a lower values favor the choice of model.

The Mardia coefficient yielded a value of 3.87, which was within the suggested score of ±5 to assume multivariate normality (Bentler 2005). These results allowed the use of the FIML estimation method to generate the standardized parameter estimates (Rodríguez and Ruíz 2008). As recommended for small sample sizes, we used non-parametric bootstrapping to test the indirect effects (Preacher and Hayes 2004; Byrne 2001).

3 Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

There were no statistically significant differences between boys and girls in any of the main characteristics of the sample (i.e. age, type of diagnosis, months since diagnosis, stage of disease, prognosis and attitude toward treatment). There were also no statistically significant differences between recovered children and children undergoing treatment in any of the key study measures.

3.2 Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 shows means and standard deviations of all variables included in the study. As shown in this table, whereas all well-being related measures showed a significant increase at T2, measures of health-related functioning problems did not significantly change from T1 to T2. Table 2 shows a correlation analysis of all the variables included in the study. As NE was not related to changes in BF (r = −.004, n.s.), satisfaction with life (r = .20, n.s.) or health-related functioning problems (r = .07, n.s.), we focused on PE for this study.

3.3 Structural Model

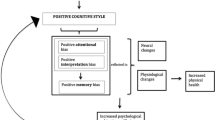

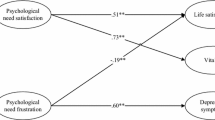

We hypothesized and tested two distinct plausible structural models including the three selected variables that have theoretically shown a significant relationship with LS: personal strengths (i.e., love, gratitude and vitality), BF and health-related functioning problems. Both models proposed changes in health-related functioning problems (Whitaker et al. 2013), changes in personal strengths (Gillham et al. 2011) and changes in BF (Meyerson et al. 2011) as predictors of changes in LS. We tested whether personal strengths and BF predicted LS directly or through a third variable: through changes in BF (Fig. 1) or though changes in personal strengths (Fig. 2). Moreover, both models tested whether the relationship between PE and changes in BF was mediated by personal strengths. Goodness of fit indicators for each model is shown in Table 3.

According to the criteria described above, model 2 presented better fit indices. However, since the fit of this model was poor, re-specification was conducted by removing paths with non-significant p values (consecutively, Love 1 → BF 2; Vitality 2 → LS 2; Gratitude 1 → Gratitude 2; BF 2 → Vitality 2; BF 2 → Love 2; BF 2 → LS 2; PE 1 → BF 2; Love 1 → Love 2; PE → Love 1). Following the recommendations of the modification indices, two new significant paths were added (Gratitude 2 → Love 2; LS 1 → Love 2; Gratitude 1 ↔ Vitality 1). Model 2R yielded favorable fit indices (Table 3). This model showed a direct effect of health-related functioning problems on changes in LS over time and an indirect effect of changes in BF on changes in LS through the strengths of love and gratitude. In other words, the relationship between BF and LS is fully mediated by two psychological strengths (i.e., gratitude and love). The reverse sequence (i.e., Love 2 → Gratitude 2) was also tested showing worse fit indices.

According to the model, changes in BF over time help to develop gratitude in children, which in turn, promotes the personal strength of love. Love partially mediated changes in LS at T2. Finally, the strengths of vitality and gratitude at T1 fully mediated the relationship between PE and changes in BF over time. In other words, the direct relationship between PE and changes in BF was no longer significant after mediators were factored into the model. Testing mediators through this multiple mediation analysis allowed us to know the relative regression weights of these two personal strengths. In this case, vitality was a stronger mediator than gratitude (see Fig. 3).

To analyze whether the indirect effects were significant, a bias-corrected bootstrap estimation (2000 bootstrap samples with 95 % confidence interval) was performed (MacKinnon et al. 2004). Mediation is supported if zero is not included in any confidence interval. Results showed that all indirect effects were significant (Table 4).

4 Discussion

The study of coping in children with life threatening illnesses has recently shifted focus from the study of psychological symptoms to the study of positive mental health resources (Klassen et al. 2011; Hedström et al. 2004). In this study, we explored predictors of LS in seriously-ill children. Research to date demonstrates that those who typically experience high levels of LS accrue many benefits. These benefits may include positive outcomes in intrapersonal, interpersonal, vocational, health and educational arenas (Huebner et al. 2005; Helliwell et al. 2013). The construct of LS is particularly relevant for children with a life threatening illness. Research has shown that low levels of LS are predictive of a variety of negative outcomes, including psychopathological symptoms (depression, anxiety, low self-efficacy, loneliness) and physical health problems (Huebner et al. 2005). Taken together, research suggests that the assessment of LS and its predictors in children may provide important information to promote positive outcomes and prevent subsequent psychological problems.

Previous literature suggests that BF, character strengths, and health-related quality of life have an important role in children and adolescents coping with an illness, but did not address whether children actually derive benefit from this difficult experience by finding benefits or building strengths of character. Therefore, as a way of addressing some of the gaps in the existing literature, this study examined the dynamics among these factors that seem to be related to and/or influence LS using a longitudinal design.

The first hypothesis was that health-related functioning problems can predict a decrease in LS. Our results confirmed that health-related functioning problems are inversely related to changes in LS over time, which is consistent with previous studies (Zebrack and Chesler 2002; Whitaker et al. 2013).

The second hypothesis, closer to a positive mental health perspective, predicted that changes in BF over time and changes in character strengths might mediate changes in LS over time (Meyerson et al. 2011; Gillham et al. 2011). According to the model, changes in BF indirectly predicted changes in LS over time. The relationship between changes in BF and changes in LS was fully mediated by love and gratitude. This model suggests that changes in BF over time may help an individual to build or develop gratitude, which in turn, helps to increase his or her disposition to love, which is ultimately related with positive changes in LS. This result is consistent with previous research that found that changes in BF lead to the strengthening of character (Peterson et al. 2008). This indirect relationship between BF and LS through third variables has been suggested in previous research (Triplett et al. 2012). These studies confirm that although there is a positive relationship between reported growth and adjustment, this relationship is not as simple as was previously expected

In regard to the factors that contribute to perceived benefits, vitality and gratitude at T1 fully mediated the association between PE and changes in BF, such that PE ‘operate’ through these strengths to increase BF over time. Therefore, children who have high levels of PE are likely to report greater BF over time. This is, at least in part, due to their personal strengths of gratitude and vitality. Consistent with Fredrickson’s (2001) “broaden and build” theory, this “building effect” of PE and personal strengths is particularly useful in contexts of chronic stress, where such resources can often become depleted (Tugade and Fredrickson 2002). PE promote psychological resources that provide the cognitive context for finding positive meaning (Fredrickson et al. 2003; Tugade and Fredrickson 2002). Thus, character strengths may predict growth over time (Peterson et al. 2006). Furthermore, NE was not related to changes in BF. These results confirm that BF and other positive changes following highly stressful events seem to reflect a positive outcome in its own right and not a mere lack or a reduction of distress (Meyerson et al. 2011; Chaves et al. 2013).

Our analyses highlighted that gratitude, love and vitality play important roles in increasing LS over the course of a child’s experience with illness. Although physical illness may place children at greater risk of poor psychological adjustment outcomes (Compas et al. 2012), these three character strengths may help children find positive meaning in their life threatening illnesses, which may in turn promote better adjustment (Peterson et al. 2006; Proyer et al. 2013).

Gratitude has been found to be a significant factor in helping people to cope with traumatic experiences (Fredrickson et al. 2003). Several studies have shown that interventions promoting gratitude reduced negative affect and increased levels of positive affect, LS, and optimism about the future (Emmons and McCullough 2003; Bono and McCullough 2006; Proyer et al. 2012). Gratitude also increases prosocial behaviors such (e.g. kindness) and strengthens social relationships (Tsang 2006). Thus, a grateful attitude may help the individual find positive meaning in negative circumstances (Emmons and McCullough 2003). Specifically, those who are ill may become more aware of the needs of others and also become more willing to help them. Besides these psychological benefits, gratitude is associated with physiological changes (McCraty et al. 1995) and with fewer symptoms of illness (Emmons and McCullough 2003). Thus far, these beneficial effects of gratitude have been mainly described in adult samples. In one of the few existing pediatric studies, Froh et al. (2009) found that there was a positive association between gratitude and positive affect, satisfaction with life, optimism, social support, and prosocial behavior, and a negative association with physical symptoms in healthy children and adolescents. Additionally, Shoshani and Slone (2013) found that gratitude was a significant predictor of students’ LS.

Love and feeling loved provide emotional security and confidence which allow children to cope with daily stress more effectively (Hazan 2004). Caring relationships can buffer people from adversity and pathology as well as enhance their health and well-being (Fredrickson 2013). A recent study showed that perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between PE and health benefits, such as increases in vagal tone (Kok et al. 2013). Performing acts of love for others may help an individual find meaning and purpose and thereby create more LS (Frankl 1946; Otake et al. 2006).

Vitality can be described as an aspect of well-being related to the subjective experience of energy and feeling full of life (Ryan and Frederick 1997). Vitality is a personal and emotional strength. It is comprised of both physical components (feeling well, without fatigue or illness) and psychological components (feeling motivated, satisfied with yourself and with others, etc.). Being enthusiastic or feeling full of life can be the result of certain habits, thoughts or behaviors. It may also become a protective factor since it reflects the availability of sufficient self-regulatory resources and energy to successfully cope the challenges of daily life (Ryan and Frederick 1997; Wood et al. 2011).

This study has some limitations. First, the sample includes some very young children. Although we took careful precautions to minimize reporting difficulties (e.g. providing visual aids such as thermometers to facilitate children’s comprehension of the response options and reading each item slowly to the child when needed), we cannot be entirely sure that children of all ages understood the scales in the same way. Second, extremely-ill children or those who lacked the necessary language skills, attention span, or cognitive abilities to complete a questionnaire were excluded, to ensure the quality of the study, but this may limit the generalization of the results. Third, the sample has different diagnoses represented that may have an impact upon results. It would be interesting for future research to focus on larger sample sizes and examining the relationship between illness types and the scales used.

Yet, despite these limitations, we believe that this study makes some important contributions to the current literature in the field. This is the first study, as far as we know, that examines the relationships among these variables taken as a whole in a pediatric sample exposed to serious difficulties. We explored associations between LS and conceptually-relevant variables previously found to be associated with LS in adults and hypothesized that they played similar roles in young people. Furthermore, most of these associations have only been previously explored by using cross-sectional designs (Meyerson et al. 2011). Thus, this study, using SEM, sheds light on possible causal roles of these variables on LS and on how PE may generate BF through character strengths.

In conclusion, these findings provide new evidence that PE, BF, love, gratitude and vitality actively help children create desirable outcomes under adverse life circumstances. Previous theories proposed that PE and the building of new psychological resources may help people better cope with their daily difficulties (Fredrickson 2002). Our model suggests that children may become more satisfied with life because they build resources that help them deal with difficult situations during illness. These results are an important starting point for designing interventions aimed at increasing the LS of children with serious illnesses. Interventions aimed at enhancing PE or recalling positive experiences, as well as strengths-based approaches for working with these children may help them to perceive more positive changes after their diagnoses and, in turn, feel more satisfied about their lives.

While resilience and positive adjustment were once widely considered to be rare characteristics held by extraordinary individuals, the construct of BF is now generally believed to be a common trait “that results from the operation of basic human adaptational systems” (Masten 2001). This study helps to identify specific causal pathways to positive adjustment and provides a clearer and broader picture of children’s responses to highly stressful events. From a positive psychology perspective, this study helps to make evident what factors underlie a child’s ability to positively cope with illness. Thus, our study might help delineate recommendations for future interventions with these children in order to prevent psychopathological symptoms and promote the development of positive resources.

Notes

Authors defined “BF” as “the positive effects that result from a traumatic event” (Meyerson et al. 2011), while resilience has been defined as “a dynamic developmental process reflecting evidence of effective coping and adaptation despite significant life adversity” (Masten 2001). BF does not necessarily reflect positive adjustment. Despite the differences, these terms have conceptual correspondence and, thus, both constructs are mentioned in this introduction.

The present study was part of a larger longitudinal study on the work of organizations and foundations working with children in hospitals. Children, aged 5–18, and their parents were contacted. 118 families were initially contacted. Nine of them declined to participate and nine showed difficulties in making an appointment. Finally, 100 families were considered to conduct different studies on well-being in children with life-threatening illnesses. For this study, we specifically focused on children from 7 to 18 as there are some variables that require a level of cognitive development that cannot be evaluated properly in younger children (such as BF).

References

Bennett, D. S. (1993). Depression among children with chronic medical problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 19, 149–169.

Bentler, P. (2005). EQS structural equations program manual. Encino: Multivariate Software.

Block, J., & Kremen, A. M. (1996). IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 349–361. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.349.

Bono, G., & McCullough, M. E. (2006). Positive responses to benefit and harm: Bringing forgiveness and gratitude into cognitive psychotherapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20, 147–158. doi:10.1891/jcop.20.2.147.

Bower, J. E., Moskowitz, J. T., & Epel, E. (2009). Is benefit finding good for your health? Pathways linking positive life changes after stress and physical health outcomes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 337–341. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01663.x.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with amos, eqs, and lisrel: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. International Journal of Testing, 1, 55–86. doi:10.1207/S15327574IJT0101_4.

Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Cann, A., & Hanks, E. (2010). Positive outcomes following bereavement: paths to posttraumatic growth. Psychologica Belgica, 50, 125–143.

Canning, E. H., Canning, R. D., & Boyce, W. T. (1992). Depressive symptoms and adaptive style in children with cancer. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 1120–1124. doi:10.1097/00004583-199211000-00021.

Chaves, C., Vázquez, C., & Hervás, G. (2013). Benefit finding and well-being in children with life threatening illnesses: An integrative study. Terapia Psicologica, 31, 7–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082013000100006

Cohen, S., Alper, C. M., Doyle, W. J., Treanor, J. J., & Turner, R. B. (2006). Positive emotional style predicts resistance to illness after experimental exposure to rhinovirus or influenza A virus. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 809–815. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000245867.92364.3c.

Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9, 361–368. doi:10.1037/a0015952.

Collins, J. J., Byrnes, M. E., Dunkel, I. J., Lapin, J., Nadel, T., Thaler, H. T., & Portenoy, R. K. (2000). The measurement of symptoms in children with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 19, 363–377.

Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Dunn, M. J., & Rodriguez, E. M. (2012). Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 455–480. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143108.

Cremeens, J., Eiser, C., & Blades, M. (2007). Brief report: Assessing the impact of rating scale type, types of items, and age on the measurement of school-age children’s self-reported quality of life. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 132–138. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsj119.

Cummins, R. A., & Lau, A. D. L. (2005). Personal wellbeing index: School children (PWI-SC) (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Deakin University. Retrieved from http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/instruments/wellbeing_index.htm

Currier, J. M., Hermes, S., & Phipps, S. (2009). Children’s response to serious illness: Perceptions of benefit and burden in a pediatric cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34, 1129–1134. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsp021.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. E. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377–389. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377.

Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist, 55, 647–654. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.647.

Frankl, V. (1946). Man’s search for meaning. New York: Washington Square Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300–319. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2002). Positive emotions. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. López (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 120–134). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Love 2.0. New York: Hudson Street Press.

Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 365–376. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365.

Froh, J. J., Yurkewicz, C., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Gratitude and subjective well-being in early adolescence: Examining gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 633–650. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.006.

Gillham, J., Adams-Deutsch, Z., Werner, J., Reivich, K., Coulter-Heindl, V., Linkins, M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Character strengths predict subjective well-being during adolescence. Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 31–44.

Gimenez, M. (2010) La medida de las fortalezas psicológicas en adolescentes (VIA-Y): Relación con Clima Familiar, psicopatología y bienestar psicológico (Doctoral dissertation). Complutense University, Madrid Retrieved from http://eprints.ucm.es/11578/

Greenspoon, P. J., & Saklofske, D. H. (2001). Toward an integration of subjective well-being and psychopathology. Social Indicators Research, 54, 81–108.

Hazan, C. (2004). Love. In C. Peterson & M. E. P. Seligman (Eds.), Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (pp. 303–324). Washington: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press.

Hedstrom, M., Haglund, K., Skolin, I., & von Essen, L. (2003). Distressing events for children and adolescents with cancer: Child, parent, and nurse perceptions. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 20, 120–132.

Hedström, M., Skolin, I., & von Essen, L. (2004). Distressing and positive experiences and important aspects of care for adolescents treated for cancer: Adolescent and nurse perceptions. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 8, 6–17. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2003.09.001.

Helgeson, V. S., Reynolds, K. A., & Tomich, P. L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 797–816. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R. & Sachs, J. (Eds.). (2013). World happiness report. (Mandated by the General Assembly of the United Nations). New York: The Earth Institute, Columbia University.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychology International, 12, 231–240. doi:10.1177/0143034391123010.

Huebner, E. S., Suldo, S. M., & Valois, R. F. (2005). Children’s life satisfaction. In K. A. Anderson & L. H. Lippman (Eds.), What do children need to flourish? Conceptualizing and measuring indicators of positive development (pp. 41–59). New York: Springer.

Huebner, E. S., Valois, R. F., Suldo, S. M., Smith, L. C., McKnight, C. G., Seligson, J. L., & Zullig, K. J. (2004). Perceived quality of life: A neglected component of adolescent health assessment and intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34(4), 270–278.

Joseph, S., Murphy, D., & Regel, S. (2012). An effective–cognitive processing model of posttraumatic growth. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 19, 316–325.

Klassen, A. F., Anthony, S. J., Khan, A., Sung, L., & Klaassen, R. (2011). Identifying determinants of quality of life of children with cancer and childhood cancer survivors: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 19, 1275–1287. doi:10.1007/s00520-011-1193-x.

Kok, B. E., Coffey, K. A., Cohn, M. A., Catalino, L. I., Vacharkulksemsuk, T., Algoe, S. B., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). How positive emotions build physical health: Perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between positive emotions and vagal tone. Psychological Science, 24, 1123–1132.

Larsen, J. T., Hemenover, S. H., Norris, C. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2003). Turning adversity to advantage: On the virtues of the coactivation of positive and negative emotions. In L. G. Aspinwall & U. M. Staudinger (Eds.), A psychology of human strengths: Perspectives on an emerging field (pp. 211–226). Washington: American Psychological Association.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56, 227–238. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227.

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tiller, W. A., Rein, G., & Watkins, A. D. (1995). The effects of emotions on short-term heart rate variability using power spectrum analysis. American Journal of Cardiology, 76, 1089–1093.

Meyerson, D. A., Grant, K. E., Carter, J. S., & Kilmer, R. (2011). Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 949–964.

Otake, K., Shimai, S., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., Otsui, K., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindnesses intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 361–375. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-3650-z.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: the development and validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strenghts for Youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 891–909. doi:10.1007/s10902-005-3648-6.

Peterson, C., Park, N., Pole, N., D’Andrea, W., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2008). Strengths of character and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 214–217.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Greater strengths of character and recovery from illness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 17–26. doi:10.1080/17439760500372739.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2003). Character strengths before and after September 11. Psychological Science, 14, 381–384. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.24482.

Phipps, S., Long, A. M., & Ogden, J. (2007). Benefit finding scale for children: Preliminary findings from a childhood cancer population. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 1264–1271. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsl052.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. doi:10.3758/BF03206553.

Pressman, S. D., & Cohen, S. (2012). Positive emotion word use and longevity in famous deceased psychologists. Health Psychology, 31(3), 297.

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2013). What good are character strengths beyond subjective well-being? The contribution of the good character on self-reported health-oriented behavior, physical fitness, and the subjective health status. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 222–232.

Proyer, R., Ruch, W., & Buschor, C. (2012). Testing strengths-based interventions: A preliminary study on the effectiveness of a program targeting curiosity, gratitude, hope, humor, and zest for enhancing life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 275–292. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9331-9.

Rodríguez, M., & Ruíz, M. (2008). Atenuación de la asimetría y de la curtosis de las puntuaciones observadas mediante transformaciones de variables: Incidencia sobre la estructura factorial. Psicológica, 29, 205–227.

Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personality, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65, 529–565. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1993). On the power of positive thinking: The benefits of being optimistic. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2, 26–30. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770572.

Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2013). Middle school transition from the strengths perspective: Young adolescents’ character strengths, subjective well-being, and school adjustment. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 1163–1181.

Triplett, K. N., Tedeschi, R. G., Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., & Reeve, C. L. (2012). Posttraumatic growth, meaning in life, and life satisfaction in response to trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4, 400–410. doi:10.1037/a0024204.

Tsang, J. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: An experimental test of gratitude. Cognition and Emotion, 20, 138–148. doi:10.1080/02699930500172341.

Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2002). Positive emotions and emotional intelligence. In L. F. Barrett & P. Salovey (Eds.), The wisdom in feeling (pp. 319–340). New York: Guilford Press.

Tugade, M. M., Fredrickson, B. L., & Feldman-Barrett, L. (2004). Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality, 72, 1161–1190. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x.

Varni, J. W., Burwinkle, T. M., Katz, E. R., Meeske, K., & Dickinson, P. (2002). The PedsQLTM in pediatric cancer: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory TM Generic Core Scales, multidimensional fatigue scale, and cancer module. Cancer, 94, 2090–2106.

Whitaker, M. C., Nascimento, L. C., Bousso, R. S., & Lima, R. A. (2013). Life after childhood cancer: Experiences of the survivors. Revista brasileira de enfermagem, 66, 873–878.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Kashdan, T. B., & Hurling, R. (2011). Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the Strengths Use Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 15–19.

Yu, C. Y. (2002). Evaluating cutoff criteria of model fit Indices for latent variable models with binary and continuous outcomes. (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). University of California, Los Angeles, USA. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/download/Yudissertation.pdf

Zebrack, B., & Chesler, M. (2002). Quality of life in childhood cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 11, 132–141. doi:10.1002/pon.569.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Fundacion Lafourcade-Ponce. The authors would like to thank Cristina Lafuente for her continuous support and enthusiasm. We are also especially grateful to Cristina Cuadrado, Miriam Gil, Cristina Pozo, Cecilia del Valle and Elena Perez, members of Fundacion Pequeño Deseo, for providing contact with the children and for always being available to help. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the collaborating hospitals, doctors and children who have participated in this study. Thanks to Matthew Abrams and Jessica Carney for his assistance in improving the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chaves, C., Hervas, G., García, F.E. et al. Building Life Satisfaction Through Well-Being Dimensions: A Longitudinal Study in Children with a Life-Threatening Illness. J Happiness Stud 17, 1051–1067 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9631-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9631-y