Abstract

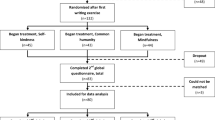

The current study examined the effect of practicing compassion towards others over a 1 week period. Participants (N = 719) were recruited online, and were assigned to a compassionate action condition or a control condition which involved writing about an early memory. Multilevel modeling revealed that those in the compassionate action condition showed sustained gains in happiness (SHI; Seligman et al. in Am Psychol 60:410–421, 2005) and self-esteem (RSES; Rosenberg in Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1965) over 6 months, relative to those in the control condition. Furthermore, a multiple regression indicated that anxiously attached individuals (ECR; Brennan et al. 1998) in the compassionate action condition reported greater decreases in depressive symptoms following the exercise period. These results suggest that practicing compassion can provide lasting improvements in happiness and selfesteem, and may be beneficial for anxious individuals in the short run.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Those under 18 years of age were not invited to participate in the study. However two participants who were 17 years old were included in the sample.

We investigated the possibility that participants’ mood at baseline (i.e. happiness, self-esteem, and depression) might predict completion or non-completion based on the exercise assigned. Several regression models were run predicting completion at 1 week, 1, 3 and 6 months with mood (SHI, RSES, CESD) and exercise condition as predictors. None of the interaction between participants’ mood and the condition assigned predicted completion of the project.

The relationship between baseline affect and degrees of freedom varied slightly across t tests because some participants failed to provide some demographic information.

The multilevel model in the prediction of self-esteem produced a main effect for income (Estimate = .07, SE = .02, t = 4.43, p < .001), and for payment status (Estimate = .23, SE = .08, t = 2.94, p = .003). Those with a higher income and those who were paid reported higher levels of self-esteem at baseline.

The multilevel model in the prediction of happiness produced a main effect for income (Estimate = .09, SE = .02, t = 4.79, p < .001), and for payment status (Estimate = .26, SE = .09, t = 2.74, p = .006). Those with a higher income, and those who were paid reported higher levels of happiness at baseline. However, a Time by payment status effect was also obtained (Estimate = −.03, SE = .01, t = −1.97, p = .05) and inspection of the estimates indicated those who were paid did not increase in happiness as much as those who joined the study without payment.

The dependent variables in this study (happiness, self-esteem and depression) were highly correlated, raising the question of independence between the constructs. It is possible, for example, that the increase in both happiness and self-esteem represent redundant effects. This issue was addressed in HLM by using “time-varying” predictors, which allows for the prediction of change in one outcome variable while controlling for co-occurring changes in the other “time-varying” predictor. In the first model, happiness was treated as the time-varying predictor of change in self-esteem. The results indicated that fluctuations in happiness significantly accounted for increases in self-esteem (Estimate = .07, SE = .03, t = 2.10, p = .04). The second model treated self-esteem as the time-varying predictor of change in happiness. The results indicated that fluctuations in self-esteem did not significantly account for increases in happiness (Estimate = .05, E = .04, t = 1.55, p = .12). These results suggests that happiness and self-esteem are inter-related but not equivalent.

The multilevel model in the prediction of depression produced a main effect for income (Estimate = −1.42, SE = .29, t = −4.91, p < .001), and for payment status (Estimate = −4.49, SE = 1.51, t = −2.98, p = .003). At the outset, those with a higher income, and those who were paid for participation reported lower levels of depression. Furthermore, a main effect for condition was obtained (Estimate = −7.21, SE = 2.29, t = −3.15, p = .002), indicating that those in the compassion group started the study feeling less depressed. The random effects for this model indicated that participants’ baseline depression scores were unrelated to their trajectory over time. Therefore, group differences at baseline should not have biased the rate of change rate obtained for the compassion and control group.

The longer multilevel model in the prediction of self-esteem also produced a main effect for income (Estimate = .06, SE = .01, t = 4.38, p < .001) such that wealthier participants had higher levels of self-esteem at baseline.

The longer multilevel model in the prediction of happiness produced a main effect for income (Estimate = .08, SE = .02, t = 4.47, p < .001), and for age (Estimate = −.009, SE = .004, t = −2.43, p = .02). Those who were younger and with a higher income, reported higher levels of happiness at baseline. A Time by payment status effect was also obtained (Estimate = −.03, SE = .01, t = −2.09, p = .04) and inspection of the estimates indicated those who were paid did not increase in happiness as much as those who joined the study without any payment.

The longer multilevel model in the prediction of depression produced a main effect for income (Estimate = −1.13, SE = .26, t = −4.28, p < .001), and a Time by age interaction effect (Estimate = .03, SE = .01, t = 2.10, p = .04). Younger participants reported greater reductions in depressive symptoms over time than older participants.

The main effects obtained in the regression analyses are not repeated here as they were previously reported in the multilevel modeling analyses.

References

Allen, N. B., & Knight, W. E. J. (2005). Mindfulness, compassion for self, and compassion for others: Implications for understanding the psychopathology and treatment of depression. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 121–147). London: Routledge.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147–178.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226–244.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York: Guilford Press.

Brown, S. L., & Brown, R. M. (2006). Selective investment theory: Recasting the functional significance of close relationships. Psychological Inquiry, 17, 1–29.

Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., Vinokur, A. D., & Smith, D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: Results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14, 320–327.

Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 644–663.

Compton, W. C. (2000). Meaningfulness as a mediator of subjective well-being. Psychological Reports, 87, 156–160.

Corcoran, K., & Fisher, J. (1987). Measures for clinical practice: A source book. New York: Free Press.

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 555–575.

Damji, T., Clement, R., & Noels, K. A. (1996). Acculturation mode, identity variation, and psychosocial adjustment. The Journal of Social Psychology, 136, 493–500.

Dulin, P. L., & Dominy, J. B. (2008). The influence of feeling positive about helping among dementia caregivers in New Zealand: Helping attitudes predict happiness. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 7, 55–69.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319, 1687–1688.

Fairchild, A. J., & Finney, S. J. (2006). Investigating validity evidence for the experiences in close relationships-revised questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 116–135.

Fleming, J. S., & Courtney, B. E. (1984). The dimensionality of self-esteem: II hierarchical facet model for revised measurement scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 404–421.

Fordyce, M. W. (1977). Development of a program to increase personal happiness. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 24, 511–521.

Fordyce, M. W. (1983). A program to increase happiness: Further studies. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30, 483–498.

Gillath, O., Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2005). An attachment-theoretical approach to compassion and altruism. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 121–147). London: Routledge.

Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2004). Formal volunteering as a protective factor for older adults’ psychological well-being. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59B, S258–S264.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524.

Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion, 8, 720–724.

Klinedinst, N. J., Clark, P. C., Blanton, S., & Wolf, S. L. (2007). Congruence of depressive symptom appraisal between persons with stroke and their caregivers. Rehabilitation Psychology, 52, 215–225.

Krause, N. M., Herzog, A. R., & Baker, E. (1992). Providing support to others and well-being in later life. Journals of Gerontology, 47, 300–311.

Krause, N., & Shaw, B. A. (2000). Giving social support to others, socioeconomic status, and changes in self-esteem in late life. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55B, S323–S333.

Krokavcova, M., Van Dijk, J. P., Nagyova, I., Rosenberger, J., Gavelova, M., Middel, B., et al. (2008). Social support as a predictor of perceived health status in patients with multiple sclerosis. Patient Education and Counseling, 73, 159–165.

Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 518–530.

Lopez, F. G., & Gormley, B. (2002). Stability and change in adult attachment style over the first-year college transition: Relations to self-confidence, coping, and distress patterns. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 355–364.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005a). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137–155.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005b). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology. Special Issue: Positive Psychology, 9, 111–131.

McAdams, D. P., & Bryant, F. B. (1987). Intimacy motivation and subjective mental health in a nationwide sample. Journal of Personality, 55, 395–413.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press.

Millar, M. G., Millar, K. U., & Tesser, A. (1988). The effects of helping and focus of attention on mood states. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 536–543.

Muraven, M., Baumeister, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (1999). Longitudinal improvement of self-regulation through practice: Building self-control strength through repeated exercise. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139, 446–457.

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2003). Volunteering and depression: The role of psychological and social resources in different age groups. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 259–269.

O’Malley, M. N., & Andrews, L. (1983). The effect of mood and incentives on helping: Are there some things money can’t buy? Motivation and Emotion, 7, 179–189.

Otake, K., Shimai, S., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., Otsui, K., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindnesses intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 361–375.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25–41.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Raupp, C. D., & Cohen, D. C. (1992). A thousand points of light illuminate the psychology curriculum: Volunteering as a learning experience. Teaching of Psychology, 19, 25–30.

Richards, J. C., & Alvarenga, M. E. (2002). Extension and replication of an internet-based treatment program for panic disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 31, 41–47.

Roberts, J. E., Gotlib, I. H., & Kassel, J. D. (1996). Adult attachment security and symptoms of depression: The mediating roles of dysfunctional attitudes and low self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 310–320.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Santor, D., Zuroff, D. C., Mongrain, M., & Fielding, A. (1997). Validating the McGill revision of the depressive experiences questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 69(1), 164–182.

Santor, D., Zuroff, D. C., Ramsay, J. O., Cervantes, P., & Palacios, J. (1995). Examining scale discriminability in the BDI and CES-D as a function of depressive severity. Psychological Assessment, 7, 131–139.

Schwartz, C., Meisenhelder, J. B., Ma, Y., & Reed, G. (2003). Altruistic social interest behaviors are associated with better mental health. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 778–785.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 61, 74–788.

Seligman, M., Steen, T., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410–421.

Simmons, R. G. (1991). Altruism and sociology. Sociological Quarterly, 32, 1–22.

Simmons, R. G., Schimmel, M., & Butterworth, V. A. (1993). The self-image of unrelated bone marrow donors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34, 285–301.

Smith, L. E., & Howard, K. S. (2008). Continuity of paternal social support and depressive symptoms among new mothers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 763–773.

Strom, L., Pettersson, R., & Andersson, G. (2000). A controlled trial of self-help treatment of recurrent headache conducted via the internet. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 722–727.

Taylor, J., & Turner, R. J. (2001). A longitudinal study of the role and significance of mattering to others for depressive symptoms. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, 310–325.

Thoits, P. A., & Hewitt, L. N. (2001). Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, 115–131.

Tice, D. M., Baumeister, R. F., Shmueli, D., & Muraven, M. (2007). Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 379–384.

Wang, S. (2005). A conceptual framework for integrating research related to the physiology of compassion and the wisdom of Buddhist teachings. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 121–147). London: Routledge.

Wei, M., Heppner, P. P., Russell, D. W., & Young, S. K. (2006). Maladaptive perfectionism and ineffective coping as mediators between attachment and future depression: A prospective analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 67–79.

Williamson, G. M., & Clark, M. S. (1989). Providing help and desired relationship type as determinants of changes in moods and self-evaluations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 722–734.

Yarcheski, A., & Mahon, N. E. (1989). A causal model of positive health practices: The relationship between approach and replication. Nursing Research, 38, 88–93.

Yinon, Y., & Landau, M. O. (1987). On the reinforcing value of helping behavior in a positive mood. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 83–93.

Yogev, A., & Ronen, R. (1982). Cross-age tutoring: Effects on tutors’ attributes. Journal of Educational Research, 75, 261–268.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a grant to the first author from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The article is based on portions of the second author’s honours’ thesis which was supervised by the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mongrain, M., Chin, J.M. & Shapira, L.B. Practicing Compassion Increases Happiness and Self-Esteem. J Happiness Stud 12, 963–981 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9239-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9239-1