Abstract

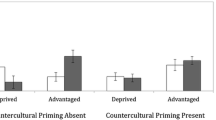

Previous research, statistically accounting for self-construal factors and thereby eliminating widely reported culture main effects in social anxiety scores between East Asians and European-Americans (Norasakkunkit and Kalick 2002 Culture, ethnicity, and emotional distress measures: The role of self-construal and self-enhancement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(1), 56–70.) suggested that social anxiety measures penalize individuals for being low on independent self-construal; therefore, cultural differences in emotional distress according to social anxiety measures may possibly misrepresent cultural differences in emotional well-being. In the current experimental study, 127 Japanese and 126 American participants were either primed or not primed to access an independent mode of thought prior to filling out two commonly used measures of social anxiety and a measure of emotional well-being. Independent priming caused social anxiety scores to decrease. Yet, independent priming did not influence levels of self-reported emotional well-being. Furthermore, although the Japanese respondents were shown to be more distressed according to both of the standardized social anxiety measures, this finding was actually reversed with respect to self-reported emotional well-being. The evidence thus points to high scores on measurements of social anxiety being directly and causally linked to low levels of independence, while no link was found between independence and emotional well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

While some have argued that the characterization of Japanese selves as interdependent is not empirically supported with attitudinal measures (e.g., Oyserman et al. 2002), others (e.g., Kitayama 2002; Uchida 2002) have argued that attitudinal measures may not be adequate for fully representing cultural influences on the structure of the self. These explicit attitudes only reflect what Kitayama calls the semantic aspect of the self, rather than the more implicit structural aspect of the self. Using an implicit measure called the implicit association test (IAT; Greenwald and Farnham 2000) thought to better capture the structural aspect of the self (Kitayama et al. 2007; Okazaki 2002), research by Uchida (2002) found that Japanese university students’ implicit values were more congruent with interdependence than with independence. This finding contrasts with findings reviewed by Oysermann et al. (2002) utilizing self-report measures, in which contemporary Japanese youth tended to endorse attitudes and values more consistent with independence and individualism. Japanese youth may be making a conscious effort to adopt individualistic values and attitudes, but this effort may not entail all levels of psychological functioning. It should also be noted that even though a given culture may be characterized as predominantly independent or interdependent, this would never preclude individual differences in the degree of such predominance. Nor would it deny that all humans are capable of accessing, at least in some degree, both independent and interdependent modes of thought even if one is a more predominant tendency than the other due to cultural influences (see Kühnen and Oysermann 2002; Cohen and Hoshino-Browne 2005).

Self-enhancement refers to the tendency to aggrandize oneself relative to similar others. Previous studies have claimed that this motivation is specific to cultures dominated by the independent self-structure like North America and is conspicuously absent among cultures dominated by an interdependent self-structure like Japan (Heine et al. 1999). Japanese have been found to be focused more on owning up to negative aspects of themselves (Kitayama et al. 1997). Contradicting this evidence, recent studies (Kobayashi and Brown 2003; Sedikides et al. 2003, 2005) have suggested that both North Americans and Japanese strategically self-enhance on traits that they value respectively. These studies have prompted methodological and empirical rejoinders (Heine 2003a, 2005; Heine et al. in press; Heine and Hamamura 2007). Efforts to adjudicate or reconcile these apparently divergent lines of research will clearly require additional time for completion.

Specific job titles have changed considerably since 1958 when Hollingshead and Redlich published their index, but their conceptual framework, based on seven echelons of occupational status and seven educational echelons depending on level of schooling completed, remains applicable and well-suited for cross-national research.

Previously used self-construal priming methods such as those employed in the United States by Gardner et al. (1999) and Trafimow et al. (1991) have not been systematically tested against alternative priming methods or standardized on diverse populations. Norasakkunkit (2003) pilot tested several approaches with Japanese and American samples, and then selected the one that is described in the current study. This self-construal priming strategy remains a work-in-progress, being the result of only a small number of pilot tests. Similar priming effects need to be replicated in a full-scale study devoted to standardizing self-construal priming methods between European-Americans and Japanese populations. For the purpose of the current study, we are reassured by the fact that the priming method proved to be reliable, in that it worked in the same direction for both Americans and Japanese with respect to its impact on the dependent variables (i.e., there was no tendency toward an interaction effect between culture and priming).

References

Brislin, R. W. (1976). Introduction. In R. W. Brislin (Ed) Translation: Approaches and research. New York: Gardner Press.

Cohen, D., & Hoshino-Browne, E. (2005). Insider and outsider perspectives on the self and world. In R. M. Sorrentino, D. Cohen, J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna, (Eds.), Culture and social behavior: The Ontario Symposium Volume 10. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Cousins, S. D. (1989). Culture and self-perception in Japan and the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(1), 124–131.

Dinnel, D. L., Kleinknecht, R. A., & Tanaka-Matsumi, J. (2002). A cross-cultural comparison of social phobia symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 24(2), 75–84.

Fiske, A. P., Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., & Nisbett, R. E. (1998). The cultural matrix of social psychology. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, & G. Linzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 915–981). Boston: The McGraw-Hill.

Gardner, W. L., Gabriel, S., & Lee, A. Y. (1999). “I” value freedom, but “we” value relationships: Self-construal priming mirrors cultural differences in judgment. Psychological Science, 10(4), 321–326.

Greenwald, A. G., & Farnham, S. D. (2000). Using the implicit association test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 1022–1038.

Heine, S. J. (2003a). Self-enhancement in Japan? A reply to Brown and Kobayashi. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 6, 75–84.

Heine, S. J. (2003b). Making sense of East Asian self-enhancement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34, 596–602.

Heine, S. J. (2005). Where is the evidence for pancultural self-enhancement? A reply to Sedikides, Gaertner, & Toguchi. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 531–538.

Heine, S. J., & Hamamura, T. (2007). In search of East-Asian self-enhancement. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(1), 1–24.

Heine, S. J., Kitayama, S., & Hamamura, T. (in press). Different meta-analyses yield different conclusions: A reply to Sedikides, Gaertner, & Vevea (2005), JPSP. Asian Journal of Social Psychology.

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1999). Is there a universal need for positive self-regard? Psychological Review, 106, 766–794.

Hollingshead, A. B., & Redlich, F. C. (1958). Social class and mental illness. New York: Wiley.

Hymes, R. W., & Akiyama, M. M. (1991). Depression and self-enhancement among Japanese and American students. Journal of Social Psychology, 131(3), 321–334.

Kitano, K. (2001). Anxiety in the college Japanese language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 85(4), 549–566.

Kitayama, S. (2002). Culture and basic psychological processes–Toward a system view of culture: Comment on Oyserman et al. (2002). Psychological Bulletin, 128, 89–96.

Kitayama, S., & Markus, H. R. (2000). The pursuit of happiness and the realization of sympathy. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective emotional well-being (pp. 113–161). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kitayama, S., & Markus, H. R., & Kurokawa, M. (2000). Culture, emotion, and emotional well-being: Good feelings in Japan and the United States. Cognition and Emotion, 14(1), 93–124.

Kitayama, S., & Markus, H. R., Matsumoto, H., & Norasakkunkit, V. (1997). Individual and collective processes in the construction of self: Self-enhancement in the United States and self-criticism in Japan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(6), 1245–1267.

Kitayama, S., Duffy, S., & Uchida, Y. (2007). Self as cultural mode of being. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology. New York: Guilford Publications, Inc.

Kobayashi, C., & Brown, J. D. (2003). Self-esteem and self-enhancement in Japan and America. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34, 567–580.

Kowner, R. (2002). Japanese body image: Structure and esteem scores in a cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Psychology, 37(3), 149–159.

Kühnen, U., & Oyserman, D. (2002). Thinking about the self influences thinking in general: Cognitive consequences of salient self-concept. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 492–499.

Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9, 371–375.

Leary, M. R. (1991). Social anxiety, shyness, and related constructs. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 161–194). New York: Academic Press.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253.

Markus, H. R., Mullally, P., & Kitayama, S. (1997). Selfways: Diversity in modes of cultural participation. In U. Neisser & D. Jopling (Eds.), The conceptual self in context: Culture, experience, self-understanding (pp. 13–61). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nishizawa, N. (2004). The “self” of Japanese teenagers: Growing up in the flux of a changing culture and society. (Doctoral dissertation, Alliant International University, 2004). Dissertation Abstracts International, 65(5-B), 2642.

Norasakkunkit, V. (2003). Self-construal priming and emotional distress: Testing for cultural biases in the concept of distress from http://krypton.mnsu.edu/∼norasv/cultpsy.htm.

Norasakkunkit, V. (2007). Pictorial versus verbal priming: Standardizing an experimental priming procedure in the United States and Japan. Paper presentation at the 7th Biennial Conference of the Asian Association of Social Psychology. Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia.

Norasakkunkit, V., & Kalick, S. M. (2002). Culture, ethnicity, and emotional distress measures: The role of self-construal and self-enhancement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(1), 56–70.

Norasakkunkit, V., Kitayama, S., & Uchida, Y. (2007). The attentional styles of socially anxious individuals in two cultures. Manuscript under preparation.

Okano, K. (1994). Shame and social phobia: A transcultural viewpoint. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 58(3), 323–339.

Okazaki, S. (1997). Sources of ethnic differences between Asian-American and White American college students on measures of depression and social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(1), 52–60.

Okazaki, S. (2000). Asian American and White American differences on affective distress symptoms: Do symptom reports differ across reporting methods? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(5), 603–625.

Okazaki, S. (2002). Cultural variations in self-construal as a mediator of distress, emotional well-being. In K. S. Kurasaki, S. Okazaki, & S. Sue (Eds.), Asian American Mental Health: Assessment theories and methods (pp. 107–122). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72.

Patterson, M. L., & Strauss, M. E. (1972). An examination of the discriminant validity of the social avoidance and distress scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 39, 169.

Prince, R. H. (1993). Culture-bound syndromes: The example of social phobias. In H. E. Lehmann (Ed.), Environment and psychopathology (pp. 55–72). New York: Springer Publishing Co.

Ruini, C., Ottolini, F., Rafanelli, C., Tossani, E., Ryff, D. D., & Fava, G. A. (2003). The relationship of psychological well-being to distress and personality. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 72, 268–275.

Russell, J. G. (1989). Anxiety disorders in Japan: A review of Japanese literature on Shinkeishitsu and Taijinkyofusho. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry, 14(4), 391–403.

Ryan, M. R., & Deci, E. L. (2006). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Sakurai, A., Nagata, T., Harai, H., Yamada, H., Mohri, I., Nakano, Y., Noda, Y., Ogawa, S., Lee, K., & Furukawa, T. (2005). Is “relationship fear” unique to Japan? Symptom factors and patient clusters of social anxiety disorder among the Japanese clinical population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 87, 131–137.

Sedikides, C., Gaertner, L., & Toguchi, Y. (2003). Pancultural self-enhancement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 60–79.

Sedikides, C., Gaertner, L., & Vevea, J. (2005). Pancultural self-enhancement reloaded: A meta-analytic reply to Heine (2005). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 539–551.

Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 580–591.

Trafimow, D., Triandis, H. C., & Goto, S. G. (1991). Some tests of the distinction between the private self and the collective self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(5), 649–655.

Uba, L. (1994). Asian-Americans: Personality patterns, identity, and mental health. New York: Guilford Press.

Uchida, Y. (2002). Culture and implicit self-construals. Paper presentation at the International Symposium on the Socio-Cultural Foundations of Cognition. Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan.

Uchida, Y., Kitayama, S., Mesquita, B., & Reyes, J. A. (2001). Interpersonal sources of happiness: The relative significance in three cultures.13th Annual convention of the American Psychological Society Toronto, Canada.

Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Kitayama, S. (2004). Cultural constructions of happiness: Theory and emprical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 223–239.

Watson, D., & Friend, R. (1969). Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33, 1–8.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by grants from Japan Foundation’s Doctoral Fellowship Program and the Office of Research and Sponsored Projects at the University of Massachusetts Boston. The authors would also like to thank Shinobu Kitayama for making data collection in Japan possible through his sponsorship of this research project at Kyoto University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Norasakkunkit, V., Kalick, S.M. Experimentally Detecting How Cultural Differences on Social Anxiety Measures Misrepresent Cultural Differences in Emotional Well-being. J Happiness Stud 10, 313–327 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9082-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9082-1