Abstract

Although childhood violence by any person is negative for children, little is known about whether violence by different family members is linked differently to problems in young adulthood, as family relationships might play different roles in children’s individual development. In this study, we examine parent and sibling violence and associations with emotional and behavioral problems, directly and indirectly via peer victimization. We used retrospective reports from 347 young adults (aged 20–24) who all reported childhood family physical violence, and we performed a path analysis using Mplus. The results showed that participants who had been victimized by a sibling only or by both a sibling and parent were more likely to report peer victimization than were participants who had been victimized by parents only. Peer victimization was, in turn, linked to more aggression, criminality, and anxiety. Theoretical and clinical implications of these results are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A majority of childhood physical violence takes place within the family in which both siblings and parents may serve as potential perpetrators (Espelage et al. 2014). To understand the impact of physical violence (from now on referred to as violence only) on emotional and behavioral problems, the family is an important context (van Berkel et al. 2018), as processes within the family are often viewed as laying the foundation for future relationships and behaviors (e.g., Hartup 1978; Howe and Recchia 2014; Tucker and Finkelhor 2017; Ladd 1992). Violence within the family might influence children’s development of social identity, teaching children that aggressive behaviors are normal within relationships (Baldry 2003). Further, violence within the family may “teach” children to be submissive and signal weakness in other relationships and potentially increase the risk of being victimized in other settings, such as by peers (Tippett and Wolke 2015; Tucker et al. 2014).

In general, being victimized to violence place children at risk of long-term negative consequences (Cater et al. 2014; Copeland et al. 2013; Hughes et al. 2017). However, although being victimized by any person is negative, the impact might be somewhat different depending on who is the perpetrator (van Berkel et al. 2018). Previous research on family violence has mainly focused on parent to child violence, overlooking victimization by other family members, such as siblings, which might influence both peer relations, and children’s behaviors and development. In the current study, we seek to expand this area of research and break down the associations between being victimized of physical violence by parent, sibling, and peer on the one hand, and emotional and behavior problems in young adulthood on the other hand.

Childhood Victimization in the Family

Physical violence is the most common type of family victimization (Källström et al. 2017; Tucker et al. 2013). Other types of family violence involve emotional and sexual abuse, as well as being neglected by a caretaker (Finkelhor et al. 2015). The focus in research has been on parents as the main perpetrators of physical violence. Research conducted in Western countries suggests that between 16% and 30% of all children are subjected to victimization by a parent or other caretaker (e.g., Annerbäck et al. 2012; Gilbert et al. 2009; Janson et al. 2011; May-Chahal and Cawson 2005). Violence by family members is often unpredictable, making the victim unable to understand, anticipate, and avoid the wrath (Meyers 2017). Parental violence has, in several studies, been linked to long-term negative outcomes such as anxiety and depression (Mandelli et al. 2015; Springer et al. 2007), drug misuse (Wright et al. 2013), criminal behavior (Widom 2000), and antisocial and impulsive behaviors (Cohen et al. 2001).

Sibling violence is a less studied form, yet some argue that it is the most common form of victimization in the family (Eriksen and Jensen 2009; Finkelhor et al. 2005). For example, in a US nation sample of 4000 children and youth 0 to 17 years old, 21.8% reported having been assaulted by a juvenile sibling the past year (Finkelhor et al. 2015). In comparison to sibling rivalry, there are no known positive consequences of sibling abuse (Meyers 2017), yet violence by a sibling is often deemed less severe than violence by a dating partner or a stranger (Khan and Rogers 2015). Sibling violence is detrimental and increases the risk of both emotional and behavioral problems for its victims, such as anxiety (Graham-Bermann et al. 1994), depression (Coyle et al. 2017), mental health distress and disorders (Dantchev et al. 2018; Tucker et al. 2013), self-harm (Bowes et al. 2014), trauma symptoms (Finkelhor et al. 2006), delinquency (van Berkel et al. 2018), substance and alcohol misuse (Button and Gealt 2010). In sum, then, physical violence is the most common type of victimization during childhood, mostly taking place within the family. Research has been shown that both parent and sibling violence is linked to emotional and behavioral problems, although most studies have been conducted on parent violence.

Childhood Peer Victimization

In addition to the association between violence in the family and future problems, violence from parents and/or sibling, might increase the risk of being a victim of peer violence (i.e. being peer victimized) (Álvarez-García et al. 2015; Espelage et al. 2012; Tippett and Wolke 2015; Wolke et al. 2015), as interaction patterns are often shaped within the family and later generalized to other interactions (Banks et al. 2004; Criss and Shaw 2005; Howe and Recchia 2014). Specifically, children and adolescents negotiate their positioning in relation to their other family members, through which they form their identity and views on themselves and on relationships (cf. Davies and Harré 1990; Harré and van Langenhove 2007). In line with the family relational schema model (Perry et al. 2001), children who experience negative treatment in the family might develop a form of “victim schema” that increase the risk of victimization outside the family. Thus, relationships within the family may serve as a model that shape children’s expectations and behaviors in future relationships (Baldry 2003; Howe and Recchia 2014; Kramer 2014). Children who are victimized by family members might develop negative emotions and submissive posture in the parent-child (Koenig et al. 2000) or sibling-to-sibling (Feinberg et al. 2012), interactions that are later carried into peer interactions making them seem easy target for peers to victimize or bully (Baldry 2003; Wolke and Samara 2004). Indeed, in a meta-analysis on parenting and peer victimization, parental abuse and neglect were the best predictors of peer victimization (Lereya et al. 2013). Also, sibling violence has been related to an increased risk for being victimized by peers (Tippett and Wolke 2015; Tucker et al. 2014; Wolke et al. 2015).

As with family violence, peer victimization is also linked to adult negative outcomes such as internalizing problems (Klomek et al. 2015; Lereya et al. 2015; Sigurdson et al. 2015), and aggression and violent behaviors (Ttofi et al. 2012). In sum, children who have been victimized by a family member are at heightened risk of being victimized by peers. Peer victimization is also linked to a variety of negative outcomes. Hence, there is some evidence for an indirect link between family violence and negative outcomes, through a heightened risk of peer victimization.

Limitations with Earlier Research

Earlier research has often lacked a holistic approach in the study of family violence. Although existing theories highlight the importance of taking a broader family systems approach (e.g., Cox and Paley 2003; Minuchin 1974), few studies have included an examination of different perpetrators in the same model, yielding piecemeal examinations of family violence. Specifically, different subsystems and dyads within the family constantly influence each other (Cox and Paley 2003; Criss and Shaw 2005; Hoffman and Edwards 2004; Howe and Recchia 2014), which stresses the importance of examining several sub-systems simultaneously to better understand the impact of family violence for children’s future emotional and behavioral development.

Additionally, examining earlier research, at least two limitations can be identified. First, the theoretical idea of an indirect link between family violence and negative outcomes via peer victimization has been tested in a piecemeal way. Studies from different research bodies have examined the different parts of this idea, but the meditational process—how family violence is linked to peer victimization, which in turn explains variations in later problems—has not been tested in its whole. There is a need to test the direct link and the indirect link in the same model to better understand the process in which children who are victimized of violence by family members develop negative outcomes. Second, the potential different impact of family violence depending on whether the family member is a parent or a sibling has not been tested in the same model. From research it is clear that both parent and sibling violence are linked to negative outcome, but it is unclear about their unique associations with peer victimization, and emotional and behavioral problems.

The Current Study

In the current study, we aim to overcome the limitations identified above with a base in two research questions. First, is the association between family physical violence on the one hand and emotional and behavioral problems on the other hand mediated by an increased risk of peer victimization? Second, do parent and sibling violence have different associations with peer victimization, and emotional and behavioral problems in young adulthood? We answer these research questions using a sample of young adults reporting on their childhood experiences of family and peer victimization, as well as their emotional and behavioral problems in young adulthood. Hence, this study represents a first attempt to examine a theoretically driven model as to how victimization to violence by different perpetrators in the family (i.e., including examinations of several sub-systems in the family) is linked to relational problems, and long-term emotional and behavioral problems in young adulthood.

Method

Participants and Procedures

In this study, we used data from a large nation-wide retrospective study (reference removed for masked review) including 2500 young Swedish adults aged 20–24 (47% males and 53% females). Participants answered questions in Swedish about their childhood experiences of victimization and current well-being and behaviors in young adulthood. Following approval of the procedure and measures of the study by the regional ethical review board, data were collected between March 2011 and December 2011. The national Statistic agency “Statistics Sweden”, which holds names, addresses, and telephone numbers to all Swedish citizens, was used to randomly select participants born between 1987 and 1991. The data were collected by a Swedish survey and marketing company and took approximately 90 min to complete. Participants received 400 SEK for their participation in the survey.

In the current study, we included only participants who reported physical violence at least once by one or more family members (biological mother, biological father, or sibling) (n = 347; 14% of the full sample). In the majority of these cases, the violence took place, and ended, before the age of 18 (74%), and the mean age of the last occasion of violence was 15 (Median = 16). Hence, for the majority of the participants in this study, the physical violence represents experiences during childhood and adolescence.

Measures

Physical Violence

We measured physical violence using 11 items. Six of these were adapted from the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ; Finkelhor et al. 2005; Hamby et al. 2004). The items were modified to cover aspects of violence by various perpetrators within and outside the family. Examples of items are: “Has anyone ever hit or attacked you on purpose with an object or weapon”, “Has anyone ever hit or attacked you without using an object or weapon”, and “Not including spanking on your bottom or hitting you with a belt, has anyone ever hit, abused, or physically hurt you in any way?” We used five additional items to cover aspects of physical violence that were not included in the JVQ, but that have been identified in research as being central aspects of physical violence experienced by children (Janson et al. 2007; May-Chahal and Cawson 2005). Examples of these items are: “Has anyone ever held you around the neck so it was hard for you to breathe”, “Has anyone ever spanked you on your bottom or hit you with a belt”, and “Has anyone ever thrown, shoved or pushed you down on the ground?” Response options ranged from 1 (Zero times) to 6 (Five times or more). Following the questions on violence, the participants were asked who the perpetrator(s) was (e.g., biological parents, step/adoptive/foster parents, sibling, peer, current partner, teacher or personnel at school, stranger).

Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Young Adulthood

In the current study, we used scales of depression and anxiety to measure emotional problems and scales of aggression and criminality to measure behavioral problems in young adulthood.

To assess anxiety and depressive symptoms, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond and Snaith 1983) was used. The HADS consists of two subscales; HADS-A includes seven items of anxiety (Cronbach’s alpha was .80), and HADS-D includes seven items of depression (Cronbach’s alpha was .66). Examples of the items are: “I feel tense or ‘wound up’”, “I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen”, “I get sudden feelings of panic”, “I feel cheerful”, “I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy”, “I feel as if I am slowed down”, and “I look forward with enjoyment to things”. Participants reported on how well the statements describe their emotional status during the past week, using a response scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much).

Aggression was measured by the Physical Aggression subscale from the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (AQ; Buss and Perry 1992). This subscale comprises nine items, such as “If somebody hits me, I hit back” and participants reported on how well the statements described themselves using a scale ranging from 1 (Extremely uncharacteristic of me) to 7 (Extremely characteristic of me). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .79.

A 19-item scale was used to measure criminal behaviors over the past year. The items have been used in previous studies on Swedish young adults (e.g. Andershed et al. 2002; Cater et al. 2014). Examples of items are: “Have you been involved in physically abusing someone, so that you believe or know, that he or she needed medical attention”, “Have you carried a weapon”, and “Have you been involved in taking a car without permission?” Response options ranged from 1 (No, that has not happened) to 5 (Has happened more than 10 times). Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .89.

Control Variables

We used three control variables in this study: Participants’ gender (1 = male), gender on the perpetrating parent (1 = mother, 2 = father, 3 = both mother and father), and whether the participant had been separated from the family before the age of 18 or not (1 = lived with parents until age 18). Gender of the participant and perpetrator were included as control variables based on ideas that relationships, as well as outcomes, might differ depending on gender (Cater et al. 2014; Evans et al. 2008; Hoglund 2007; Sullivan et al. 2006). Separation from the family might influence the behavioral and emotional outcomes, as it might put an end to the violence, and, thus break a negative development.

Statistical Analyses

We ran a path analysis using Mplus 7.11 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012) with the Robust Maximun Likelihood estimator (MLR), as some of the dependent variables were categorical. To prepare data for this analysis, we dummy coded the victimization variables to use as categorical predictors. Because three options were possible: (1) being victimized by a parent only, (2) being victimized by a sibling only, and (3) being victimized by both a parent and a sibling), we computed two dummy variables. Both dummy variables were coded so that victimization by a parent only was the reference group (0). For the first dummy variable (parent only vs. sibling only violence), being exposed by a sibling only was coded as 1, and for the second dummy variable (parent only vs. both parent and sibling violence), being victimized by both a parent and a sibling was coded as 1. Peer victimization was a categorical variable (1 = been victimized at least once; 0 = not been victimized), and the behavioral variables were continuous.

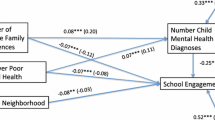

The analytical model is presented in Fig. 1. In this model, we examined the associations among violence in the family and peer victimization, and emotional (depression and anxiety) and behavioral (aggression and criminality) problems. We tested both the direct effects between family violence and problems and indirect effects via peer victimization. To test for indirect effects, we used the model indirect command of the Mplus language, and we used bootstrap sampling method (n 1000; Shrout and Bolger 2002), as it does not assume normal distributions and is suitable when using smaller sample sizes (MacKinnon et al. 2002). In the path analysis, we also included the control variables (gender of participant and perpetrator, and separation from the family before age 18 or not).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Of the 347 participants, 193 (56%) reported physical violence by a parent (58% of the girls and 52% of the boys), 102 (29%) reported physical violence by a sibling (26% of the girls and 35% of the boys), and 52 (15%) participants reported being victimized by both a sibling and a parent (16% of the girls and 14% of the boys). Of the 347 participants, 145 (42%) reported peer victimization (31% of the girls and 60% of the boys).

In Table 1, we present zero-order correlations for all study variables. As can be seen, both family violence variables were significantly correlated with peer victimization. Family violence variables also showed significant associations with some of the outcome variables, and so did peer victimization. Most outcome variables were significantly correlated with each other.

In Table 2, we report the means and standard deviations for outcomes, both for the full sample and across the control variables. As can be seen in Table 2, men reported more criminal behaviors, but significantly lower levels of anxiety than did women. Further, participants who had been victimized by both their father and their mother reported more aggressive behaviors than did participants who had been victimized by one of the parents. Finally, participants who had been separated from their home environment before the age of 18 showed significantly fewer emotional and behavior problems (anxiety, depression, and aggression) than did participants who stayed in their families at least until the age of 18.

Results from the Path Analysis Examining Direct and Indirect Effects

To examine the associations among the study variables, we adapted a path model using observed variables (see Fig. 1). This model, which included all direct and indirect paths, was just identified (i.e., a saturated model) meaning that there was an equal amount of known and unknown information, producing 0 degrees of freedom. Although saturated models do not offer fit statistics as a mean for evaluating the fit of the model, the parameter estimates can still be generated and evaluated (Hoyle 2012), and, thus, these are interpreted in the current study. The results from the analytical model are presented in Table 3 (both non-significant and significant direct and indirect effects).

Direct Effects

As can be seen in Table 3, both variables of family violence were significantly linked to peer victimization (β = .19, p < .001 and β = .12, p = .025, for the parent only vs. sibling only violence and the parent only vs. both parent and sibling violence dummy variables respectively). As parent violence was treated as the reference group and was coded as 0 on both variables, a significant estimate specifies that a change on this variable (i.e., going from parent violence only to sibling violence only/both parent and sibling violence) is associated with a change in the peer victimization variable (i.e., going from not being victimized to being victimized by peers). These variables were positively associated, and thus, the results show that participants who reported being victimized by their sibling or by both their parent and sibling were more likely to be victimized by peers than were participants who were victimized by their parents only. Concerning the links between family violence and the emotional and behavioral outcome variables, none of the eight estimates were significant. Hence, in the analytical model, family victimization was significantly linked to peer victimization, but not to emotional and behavioral behaviors.

Significant direct effects from path analysis (see Table 3 for all coefficients). * = p < .05; ** = p < .01; *** = p < .001. N = 347

Peer victimization was significantly linked to anxiety (β = .14, p = .015), criminality (β = .10, p = .014), and aggression (β = .19, p = .001). Peer victimization was not, however, significantly associated with depression (β = .07, p = .174). Hence, being victimized by peers was associated with a greater risk of reporting emotional and behavioral problems (see Fig. 2 for significant direct effects).

Indirect Effects

To examine if the indirect effects were significant, we used the model indirect command of the Mplus language. Three of the eight indirect effects were significant (see Table 3), and these were all found in the comparison between sibling violence only and parent violence only. Sibling violence only (in comparison to parent violence only) was significantly linked to anxiety (β = .03, p = .050), criminality (β = .02, p = .043), and aggression (β = .04, p = .018), via peer victimization. Hence, the link between family violence and emotional and behavioral problems was, at least partly, explained by peer victimization (only partly, as only three of the eight indirect effects were significant).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the associations among parent and sibling violence, peer victimization, and emotional and behavioral problems. With family system theory in mind, it is necessary to examine physical violence within different sub-systems in the family, and their links to emotional and behavioral problems. Such examination offers a broader understanding of children and adolescents’ experiences in the family and whether or not certain patterns of violence, within some sub-systems and by some family members, are more strongly linked to long-term emotional and behavioral outcomes. We posed two research questions. First, is the association between family physical violence on the one hand and emotional and behavioral problems on the other hand mediated by an increased risk of peer victimization? Second, do parent and sibling violence have different associations with peer victimization, and emotional and behavioral problems in young adulthood? The results showed that sibling violence and violence by both a sibling and a parent in childhood were linked to an increased risk of peer victimization, which in turn was linked to more aggression, criminality, and anxiety in young adulthood. Below we discuss these results in terms of their theoretical and practical implications.

The results of this study suggested that sibling violence might be especially important for problems in young adulthood, as more of the effects were significant for participants who had been victimized by a sibling only or a sibling in combination with a parent in comparison to participants who had been victimized by a parent only. Specifically, participants who reported being victimized by their sibling or by both their parent and sibling were more likely to be victimized by peers than were participants who reported being victimized by their parents only. Peer victimization was in turn linked to more problems in young adulthood. It is possible that violence by a parent and a sibling have different meanings for the victim. Being victimized by a sibling might have a strong association with the identity construction, given that a sibling is probably closer in age to the participant than are parents (Geldard et al. 2016). In such, victimization by a sibling can be part of a socialization process in which a positioning takes place (Davies and Harré 1990; Harré and van Langenhove 2007). Specifically, as a result of repeated interactions with a violent sibling, the person might construct a “victim schema” (Perry et al. 2001) that becomes incorporated as part of the child or adolescents’ view on him- or herself, signaling in relation to others a form of weakness (Baldry 2003). Hence, sibling violence might be specifically problematic for the development of emotional and behavioral problems during young adulthood.

However, the fact that sibling violence showed especially strong associations with the outcome variables does not mean that parent violence is unimportant for a person’s development. Numerous studies have shown clear evidence that parental abusive behaviors bring severe negative outcomes. What the current study suggests, however, is that the associations with emotional and behavioral outcomes might differ depending on who is the perpetrator in the family, suggesting that there is a need to examine violence within different sub-systems of the family. It is possible that peer victimization is a better mediator to explain the link between sibling violence and the problems, as was discussed above concerning the development of a victim schema. Other factors might play a more important role in the process concerning parent violence and its links to outcomes in young adulthood. One example might be the child’s attachment to his or her parent, which is linked to parent violence, and emotional, social, and behavioral outcomes (e.g., Jacobsen and Hofmann 1997; Muris et al. 2003). Children being victimized by parents might develop an insecure attachment style, which in turn explains development of problems in young adulthood. This hypothesis, however, needs empirical examination.

The results showed that family violence was linked to aggressive behaviors and anxiety, via peer victimization. In fact, and somewhat surprising, none of the direct associations between family violence and the emotional and behavioral outcomes were significant. The non-significant direct effects and the significant indirect effects (three out of eight) suggest that the development of emotional and behavioral problems in young adulthood might be explained, at least partly, by the fact that family violence put the child at heightened risk of experiencing peer victimization. Additionally, the indirect link to aggression, in addition to the link to anxiety, suggests that not all participants showed outcomes that would be included in a typical “victim schema” (cf. Fohring 2012; Burcar 2005). Instead, supporting the idea of a victim-offender overlap (e.g., Cater et al. 2014), the results can be interpreted as some participants showed an increased risk of developing both a victim position and an offender position, where being victimized by both siblings and peers might be part of a development of attitudes in favor of victimizing others. The result concerning aggression is in line with the social learning theory (Bandura 1977) in which aggressive behaviors are learned and later serve as guide for actions in other relationships and contexts. Hence, violence in the family, and especially sibling violence, might be important in young people’s social, emotional, and behavioral development, by influencing their schemes about themselves as a victim and/or an offender.

In this study, we controlled for three covariates. One of the covariates—whether or not the participant had been separated from the family before age 18—showed especially strong association with the outcomes, suggesting that being separated from a violent family environment before the age of 18 is positive in terms of the development of emotional and behavioral problems. This result indicates that although being victimized in the family, a separation might break a negative spiral, as it might put a stop to the violence. However, as the indirect effect of family violence on the outcomes, via peer victimization, was still significant, although we controlled for the covariates, separation might not break the development of a so called “victim schema” (Perry et al. 2001).

The findings in this study must be interpreted with its limitations in mind. First, the data did not allow a control for additional factors related to the siblings, such as gender, birth order, number of siblings, or relationship quality between the siblings. Such information might be important for the understanding of the association between family violence and emotional and behavioral problems. For example, a positive relationship with a sibling might buffer, and, thus, work as a moderator, against negative development resulting from parental violence. In future research, a further holistic approach would include examinations of more aspects concerning the sibling relationship. Second, data were cross-sectional and the findings might be a result of other underlying factors that were not controlled for and that are causing the processes of interest. Additionally, because of the cross-sectional data, we could not draw conclusions about causal relations, and whether problems reported emerged as a result of the violence being studied. However, most participant (74%) reported that the violence had taken place before age 18, and because participants reported on their current emotions and behaviors (in young adulthood), we somewhat overcame this issue and it made us more comfortable to draw conclusions about the processes of interest in this study. However, we were not able to draw conclusions about the direction of effect between family violence and peer victimization. Although theory (Perry et al. 2001) and research (Álvarez-García et al. 2015; Tippett and Wolke 2015; Wolke et al. 2015) suggest that family violence generalizes to other relationships, such as with peers, it is possible that peer victimization increases the risk of family violence. Third, the data consist of self-reported retrospective reports of violence. Although retrospective reports are often used in studies on childhood victimization, this presents a limitation concerning validity, as recollections are more negatively influenced when respondents are asked to give information on issues that happened a long time ago (Widom et al. 2004). A final limitation concerns the year of the data collection, as changes in attitudes and frequencies of violence might have taken place since 2011. Future studies should examine similar questions using more recent collected data to test the validity of the findings.

Despite the limitations, this study has important strengths. It is the first, to our knowledge, to test the idea that family violence is linked to emotional and behavioral problems via peer victimization. This presents a test of a theoretical model that has not been tested in earlier studies. Further, as we examined parent and sibling violence in the same model, we were able to test for differences in the associations regarding violence by these family members, peer victimization, and emotional and behavioral outcomes. With this examination, we overcame the common problem of piecemeal examinations. Hence, this study offers a more holistic and broader approach, both in terms of family context and across several settings (family and peers).

The results of the current study have important implications for theory and practice. Taken together, our results show that children who are victimized in two important contexts—the family environment and in peer relations—report problems with anxiety, criminality, and aggression in young adulthood. Because we test both direct and indirect effects, the results inform about important mechanisms in explaining why some participants are at heightened risk of developing both emotional and behavioral problems in young adulthood. Specifically, to understand the outcomes of sibling violence, it is necessary to consider both a development of a “victim scheme” and a process of learned aggression. Additionally, our results stress the importance for practitioners to work with violent behaviors within the family in a broader manner, paying attention also to sibling violence because it can be especially important for identity formation. Our results support the notion that sibling relationships may serve as an important training ground for other relationships. Accordingly, this study gives support to those arguing for the importance of developing family prevention programs aimed at sibling aggression and violence since it might influence how children handle conflicts outside the family (Tucker and Finkelhor 2017). Some promising findings from intervention studies show benefits of mediation and social skills training on improving siblings’ relationship quality (Smith and Ross 2007; Thomas and Roberts 2009). Such training could teach children important skills in handling conflicts, skills that can be generalized to relationships with peers. However, empirically tested interventions regarding sibling violence are still lacking and should be the next important issue to address for research on family violence. Moving forward, research should focus on how parents can be supported in dealing aggression between siblings, especially since parents seem to find this challenging (Pickering and Sanders 2017). Incorporating interventions to improve sibling relationship quality in existing family programs could be one way forward. Regardless, this study stresses the need to develop evidence-based intervention programs aimed at reducing family violence in a broader sense, in order to secure children’s well-being.

References

Álvarez-García, D., García, T., & Núñez, J. C. (2015). Predictors of school bullying perpetration in adolescence: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.007.

Andershed, H., Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Levander, S. (2002). Psychopathic traits in non-referred youths: A new assessment tool. In E. Blaauw & L. Sheridan (Eds.), Psychopaths: Current international perspectives (pp. 131–158). The Hague: Elsevier.

Annerbäck, E. M., Sahlqvist, L., Svedin, C. G., Wingren, G., & Gustafsson, P. A. (2012). Child physical abuse and concurrence of other types of child abuse in Sweden – Associations with health and risk behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 585–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.006.

Baldry, A. C. (2003). Bullying in schools and exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 713–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00114-5.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Banks, L., Burraston, B., & Snyder, J. (2004). Sibling conflict and ineffective parenting as predictors of adolescent boys' antisocial behavior and peer difficulties: Additive and interactional effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14, 99–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.01401005.x.

Bowes, L., Wolke, D., Joinson, C., Lereya, S. T., & Lewis, G. (2014). Sibling bullying and risk of depression, anxiety, and self-harm: A prospective cohort study. Pediatrics, 134, e1032–e1039. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-0832.

Burcar, V. (2005). Gestaltningar av offererfarenheter: samtal med unga män som utsatts för brott. Lund (p. 221). Sweden: Lund University.

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. P. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452.

Button, D. M., & Gealt, R. (2010). High risk behaviors among victims of sibling violence. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-009-9276-x.

Cater, Å. K., Andershed, A.-K., & Andershed, H. (2014). Youth victimization in Sweden: Prevalence, characteristics and relation to mental health and behavioral problems in young adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 1290–1302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.002.

Cohen, P., Brown, J., & Smailes, E. (2001). Child abuse and neglect and the development of mental disorders in the general population. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 981–999.

Copeland, W. E., Wolke, D., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2013). Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01259.

Coyle, S., Demaray, M. K., Malecki, C. K., Tennant, J. E., & Klossing, J. (2017). The associations among sibling and peer-bullying, social support and internalizing behaviors. Child & Youth Care Forum, 46, 895–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-017-9412-3.

Criss, M. M., & Shaw, D. S. (2005). Sibling relationships as contexts for delinquency training in low-income families. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 592–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.592.

Dantchev, S., Zammit, S., & Wolke, D. (2018). Sibling bullying in middle childhood and psychotic disorder at 18 years: A prospective cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 48, 2321–2328. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717003841.

Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20, 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1990.tb00174.x.

Eriksen, S., & Jensen, V. (2009). A push or a punch: Distinguishing the severity of sibling violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 183–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508316298.

Espelage, D. L., Low, S., & De La Rue, L. (2012). Relations between peer victimization subtypes, family violence, and psychological outcomes during early adolescence. Psychology of Violence, 2, 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027386.

Espelage, D. L., Low, S., Rao, M. A., Hong, J. S., & Little, T. D. (2014). Family violence, bullying, fighting, and substance use among adolescents: A longitudinal mediational model. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24, 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12060.

Evans, S. E., Davies, C., & DiLillo, D. (2008). Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.02.005.

Feinberg, M. E., Solmeyer, A. R., & McHale, S. M. (2012). The third rail of family systems: Sibling relationships, mental and behavioral health, and preventive intervention in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0104-5.

Finkelhor, D., Hamby, S., Ormrod, R., & Turner, H. (2005). The juvenile victimization questionnaire: Reliability, validity, and national norms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 383–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.001.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Ormrod, R. (2006). Kid’s stuff: The nature and impact of peer and sibling violence on younger and older children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 1401–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.006.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169, 746–754. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676.

Fohring S. (2012) The process of victimisation: investigating risk, reporting and service use. Edinburg: The University of Edinburgh, 217.

Geldard, K., Geldard, D., & Yin Foo, R. (2016). Counselling adolescents – The proactive approach for young people. London: Sage Publications.

Gilbert, R., Widom, C. S., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet, 373, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7.

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Cutler, S. E., Litzenberger, B. W., & Schwartz, W. E. (1994). Perceived sibling violence and emotional adjustment during childhood and adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology, 8, 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.8.1.85.

Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2004). The juvenile victimization questionnaire (JVQ): Administration and scoring manual. Durham: University of New Hampshire, Crimes Against Children Research Center.

Harré, R., & van Langenhove, L. (2007). Varieties of positioning. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 21, 393–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1991.tb00203.x.

Hartup, W. W. (1978). Perspectives on child and family interaction: Past, present, and future. In R. M. Lerner & G. B. Spanier (Eds.), Child influences on marital and family interaction: A life-span perspective (pp. 23–46). San Francisco: Academic Press.

Hoffman, K. L., & Edwards, J. N. (2004). An integrated theoretical model of sibling violence and abuse. Journal of Family Violence, 19, 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOFV.0000028078.71745.a2.

Hoglund, W. L. (2007). School functioning in early adolescence: Gender-linked responses to peer victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.683.

Howe, N., & Recchia, H. (2014). Sibling relationships as a context for learning and development. Early Education and Development, 25, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2014.857562.

Hoyle, R. H. (2016). Handbook of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2, 356–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4.

Jacobsen, T., & Hofmann, V. (1997). Children’s attachment representations: Longitudinal relations to school behavior and academic competency in middle childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 33, 703–710. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.4.703.

Janson, S., Långberg, B., & Svensson, B. (2007). Våld mot barn 2006-2007 – en nationell kartläggning [Violence against children – A national survey in Sweden 2006–2007]. Stiftelsen Allmänna Barnhuset och Karlstad universitet 2007:4.

Janson, S., Jernbro, C., & Långberg, B. (2011). Kroppslig bestraffning och annan kränkning av barn i Sverige - en nationell kartläggning 2011 [physical punishment and other types of violation of children in Sweden – A national survey 2011]. Stiftelsen Allmänna Barnhuset.

Källström, Å., Hellfeldt, K., Howell, K., Miller-Graff, L., & Graham-Bermann, S. (2017). Young adults victimized as children or adolescents: Relationships between perpetrator patterns, poly-victimization, and mental health problems. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517701452.

Khan, R., & Rogers, P. (2015). The normalization of sibling violence: Does gender and personal experience of violence influence perceptions of physical assault against siblings? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30, 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514535095.

Klomek, A. B., Sourander, A., & Elonheimo, H. (2015). Bullying by peers in childhood and effects on psychopathology, suicidality, and criminality in adulthood. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2, 930–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00223-0.

Koenig, A. L., Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. A. (2000). Child compliance/noncompliance and maternal contributors to internalization in maltreating and nonmaltreating dyads. Child Development, 71, 1018–1032. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00206.

Kramer, L. (2014). Learning emotional understanding and emotion regulation through sibling interaction. Early Education and Development, 25, 160–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2014.838824.

Ladd, G. W. (1992). Themes and theories: Perspectives on processes in family peer relationships. In R. D. Park & G. W. Ladd (Eds.), Family–peer relationships: Models of linkage (pp. 3–34). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lereya, S. T., Samara, M., & Wolke, D. (2013). Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: A meta-analysis study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 1091–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.001.

Lereya, S. T., Copeland, W. E., Costello, E. J., & Wolke, D. (2015). Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: Two cohorts in two countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2, 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00165-0.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.83.

Mandelli, L., Petrelli, C., & Serretti, A. (2015). The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: A meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression. European Psychiatry, 30, 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.007.

May-Chahal, C., & Cawson, P. (2005). Measuring child maltreatment in the United Kingdom: A study of the prevalence of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 969–984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.009.

Meyers, A. (2017). Lifting the veil: The lived experience of sibling abuse. Qualitative Social Work, 16, 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325015612143.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families & family therapy. Oxford: Harvard University Press.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & van den Berg, S. (2003). Internalizing and externalizing problems as correlates of self-reported attachment style and perceived parental rearing in normal adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 12, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-003-0298-2.

Muthén, B. O., & Muthén, L. K. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Author.

Perry, D. G., Hodges, E. V. E., & Egan, S. K. (2001). Determinants of chronic victimization by peers: A review and new model of family influence. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 73–104). New York: Guilford Press.

Pickering, J. A., & Sanders, M. R. (2017). Integrating Parents' views on sibling relationships to tailor an evidence-based parenting intervention for sibling conflict. Family Process, 56, 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12173.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422.

Sigurdson, J. F., Undheim, A. M., Wallander, J. L., Lydersen, S., & Sund, A. M. (2015). The long-term effects of being bullied or a bully in adolescence on externalizing and internalizing mental health problems in adulthood. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0075-2.

Smith, J., & Ross, H. (2007). Training parents to mediate sibling disputes affects children's negotiation and conflict understanding. Child Development, 78, 790–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01033.x.

Springer, K. W., Sheridan, J., Kuo, D., & Carnes, M. (2007). Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 517–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.01.003.

Sullivan, T. N., Farrell, A. D., & Kliewer, W. (2006). Peer victimization in early adolescence: Association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457940606007X.

Thomas, B. W., & Roberts, M. W. (2009). Sibling conflict resolution skills: Assessment and training. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18, 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-008-9248-4.

Tippett, N., & Wolke, D. (2015). Aggression between siblings: Associations with the home environment and peer bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 41, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21557.

Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., & Lösel, F. (2012). School bullying as a predictor of violence later in life: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.05.002.

Tucker, C. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2017). The state of interventions for sibling conflict and aggression: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18, 396–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015622438.

Tucker, C. J., Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Shattuck, A. (2013). Association of sibling aggression with child and adolescent mental health. Pediatrics, 132, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3801.

Tucker, C. J., Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Shattuck, A. M. (2014). Sibling and peer victimization in childhood and adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 1599–1606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.007.

van Berkel, S. R., Tucker, C. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2018). The combination of sibling victimization and parental child maltreatment on mental health problems and delinquency. Child Maltreatment, January 8, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517751670.

Widom, C. S. (2000). Childhood victimization: Early adversity, later psychopathology. National institute of justice journal, 2000. National Institute of Justice Journal, 242, 3–9.

Widom, C. S., Raphael, K. G., & DuMont, K. A. (2004). The case for prospective longitudinal studies in child maltreatment research: Commentary on Dube, Williamson, Thompson, Felitti, and Anda (2004). Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.009.

Wolke, D., & Samara, M. M. (2004). Bullied by siblings: Association with peer victimisation and behaviour problems in Israeli lower secondary school children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1015–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00293.x.

Wolke, D., Tippett, N., & Dantchev, S. (2015). Bullying in the family: Sibling bullying. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2, 917–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00262-X.

Wright, E. M., Fagan, A. A., & Pinchevsky, G. M. (2013). The effects of exposure to violence and victimization across life domains on adolescent substance use. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37, 899–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.010.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Glatz, T., Källström, Å., Hellfeldt, K. et al. Physical Violence in Family Sub-Systems: Links to Peer Victimization and Long-Term Emotional and Behavioral Problems. J Fam Viol 34, 423–433 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-0029-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-0029-6