Abstract

Although authentic leadership has been shown to inform a host of positive outcomes at work, the literature has dedicated little attention to identifying its personal antecedents and effective means to enhance it. Building on strong theoretical links and initial evidence, we propose mindfulness as a predictor of authentic leadership. In 2 multi-source field studies (cross-sectional and experimental), we investigated (a) the role of leaders’ trait mindfulness and (b) the effectiveness of a low-dose mindfulness intervention for perceptions of authentic leadership. The results of both studies confirmed a positive relation between leaders’ trait mindfulness and authentic leadership as rated by both followers and leaders. Moreover, the results of study 2 showed that the intervention increased authentic leadership via gains in leaders’ mindfulness, as perceived by both followers and leaders. In addition, we found that the intervention positively extended to followers’ work attitudes via authentic leadership. The paper concludes with a discussion of the study’s implications for leadership theory and leader development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Amidst the public’s growing dissatisfaction with business executives, stemming from organizational malpractice and leadership failure, researchers and practitioners have increased their focus on alternative leadership approaches that allow to operate in line with values while still meeting the prescribed performance standards (Gardner, Cogliser, Davis, & Dickens, 2011; Kinsler, 2014). Many see authentic leadership as the prototype of such an alternative approach—a kind of “root concept” that forms the basis for other positive leadership behaviors like transformational or ethical leadership (e.g., Ilies, Morgeson, & Nahrgang, 2005). Stemming from the Greek word authentikós (meaning real), authentic leadership has been defined via four core dimensions focusing on self-awareness, a trustful relationship with followers where one is able to share one's true thoughts and feelings, open and unbiased processing, and strong moral values and congruency of actions (Gardner et al., 2011; Neider & Schriesheim, 2011).

Authentic leadership has been shown to have benefits for followers’ job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behaviors, justice perceptions, and task, group, and organizational performance (Banks, McCauley, Gardner, & Guler, 2016; Hoch, Bommer, Dulebohn, & Wu, 2018; Schuh, Zheng, Xin, & Fernandez, 2017). Although this evidence is well-established, organizational scholars surprisingly still focus more on the outcomes and mechanisms of authentic leadership (Gardner et al., 2011) rather than on how to foster it. To date, there is scarce research on the personal antecedents of authentic leadership and thus few answers about how to develop appropriate trainings. Addressing this question is of great practical importance, as organizations need guidance in how to hire and train leaders who can act and lead in an authentic way (Cooper, Scandura, & Schriesheim, 2005). As noted by Avolio and Walumbwa (2014), “the practice community has certainly responded to this need by offering a growing number of training programs” but these efforts are often “premature” and likely to “end up on the junk heap” if the concept of authentic leadership and the associated training efforts are not researched and validated in a scientifically rigorous way (p. 334). Thus, it is crucial to start testing training methods in order to offer evidence-based advice on how to improve and sustain authentic leadership.

Authentic leadership is not a specific leadership style per se, but rather an integral part of a leader’s way of being (Cooper et al., 2005; Gardner et al., 2011). Authentic leadership training, thus, requires a holistic approach that accounts for the whole person: one's individual character, values, and preferences. Traditional leadership trainings focusing merely on a specific set of skills (e.g., goal setting or intellectual stimulation; Barling, Weber, & Kelloway, 1996; Dvir, Eden, Avolio, & Shamir, 2002) will fall short in this case. In addition, training leaders to behave in a standardized, presumably ideal, way (e.g., using images and metaphors in a speech; Antonakis, Fenley, & Liechti, 2011; Emrich, Brower, Feldman, & Garland, 2001; Naidoo & Lord, 2008) without considering if this behavior is congruent or incongruent with a person’s character or values, may increase the chance that both, leaders themselves and followers, perceive the trained behavior as inauthentic. Therefore, an effective approach to increase authentic leadership will necessarily protect and even promote each individual’s “true core”. It will help individuals to find out who they really are, what they stand for, and how they can communicate that in an honest and transparent way to build meaningful relationships with followers.

One factor that has been theorized to show a strong conceptual link to authentic leadership is mindfulness (e.g., Kinsler, 2014; Reb, Sim, Chintakananda, & Bhave, 2015). Being mindful means paying attention to present-moment experiences in a receptive and non-judgmental way (Bishop et al., 2004; Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). In the present work, we treat mindfulness as a personal antecedent to and a holistic means (Amaro, 2015; Gause & Coholic, 2010) of training authentic leadership. Mindfulness promotes authenticity by allowing self-discovery and self-awareness, leading to more self-concordant goal setting (Kinsler, 2014) and the identification of one’s strengths and weaknesses (Brown & Ryan, 2003). For example, instead of pretending to be the charismatic, confident, or inspiring leader that they do not perceive themselves to be, leaders may learn to be more attentive and accepting of their true self . By being mindful, those leaders may be able to effectively communicate their needs (e.g., their desire to “stick to the facts”) to subordinates, thereby increasing authenticity and avoiding misunderstanding. In short, mindfulness has the potential to promote an authentic way of being and has consistently shown to be malleable (Eberth & Sedlmeier, 2012; Lomas et al., 2017).

In two studies—a multi-source cross-sectional survey study (study 1) and a multi-source field experiment (study 2)—we tested (a) whether leaders’ trait mindfulness is related to follower- and leader-rated authentic leadership (study 1 and study 2) and (b) if a mindfulness intervention is able to causally impact leaders’ level of mindfulness and, in turn, their authentic leadership behavior (as perceived by themselves and their subordinates). Furthermore, we tested (c) whether that change also extends to followers’ job attitudes, such as job satisfaction and interpersonal justice perceptions (study 2). A recent review on the outcomes of mindfulness and meditation interventions for managers and leaders (Donaldson-Feilder, Lewis, & Yarker, 2018) offers initial evidence that mindfulness interventions may improve aspects of leaders’ well-being and leadership capability. However, the review also highlighted a number of shortcomings among extant intervention studies, including poor research designs that lack internal validity (e.g., no control groups or quasi-experimental studies) and the omission of follower outcomes. Furthermore, none of the included studies provided outcomes for leaders’ direct reports or assessed whether mindfulness was the mechanism through which the intervention improved further outcomes. We addressed these concerns with two multi-source field studies, one of which is a rigorous, randomized, controlled experiment. Furthermore, we assessed whether mindfulness is in fact the mechanism through which the intervention’s effects are translated into leadership behavior and whether said effects extend to follower outcomes.

In addressing the role of mindfulness for authentic leadership, our present work makes important contributions to the literature. Firstly, it adds to the authentic leadership literature by identifying a theoretically and practically meaningful antecedent of authentic leadership behavior, as well as an effective means of enhancing authentic leadership through training (e.g., Gardner et al., 2011; Kinsler, 2014).

Secondly, it contributes to the literature on mindfulness in the work context (for a recent review, see Good et al., 2016). While there is an incipient body of research on the benefits of mindfulness for leadership behavior, extant studies have predominantly investigated the role of leaders’ trait mindfulness for other leadership approaches, such as transformational and abusive supervision or servant leadership (Liang et al., 2016; Pinck & Sonnentag, 2017; Pircher Verdorfer, 2016). Our focus on authentic leadership not only advances the behavioral outcome domain of leader trait mindfulness at work but also represents a straightforward and parsimonious approach to directly target the essence of positive leadership (Ilies et al., 2005). Additionally, by testing the effect of a mindfulness training, our study paves the way for future intervention studies that may target a range of additional (leader) behaviors at work.

Thirdly, it adds to the nascent body of leadership development (Day, Fleenor, Atwater, Sturm, & McKee, 2014). While a few valuable trainings have been developed for transformational (Barling et al., 1996; Dvir et al., 2002) or charismatic leadership (Antonakis et al., 2011; Frese, Beimel, & Schoenborn, 2003), the literature still features few interventions that are theoretically meaningful and methodologically sound. Furthermore, there is practical value in identifying tools that organizations can use to promote mindfulness and, by extension, authentic leadership. Organizations with access to effective and affordable interventions may be able to shift focus from personnel selection (i.e., hiring mindful individuals) to personnel development (i.e., enhancing the mindfulness of any current employee or new hire), thereby targeting a much wider range of individuals.

Theoretical Background

Authentic Leadership

The psychological leadership literature has borne many definitions and discussions of authenticity and authentic leadership in the past years (for an overview, see, e.g., Iszatt-White & Kempster, 2018). Despite a number of significant differences in those conceptualizations, there is also much overlap. As defined by positive organizational psychology (Luthans, Luthans, Hodgetts, & Luthans, 2001), authentic leadership refers to a pattern of leader behavior that both builds upon and facilitates positive psychological capacities in order to foster positive self-development (Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, 2008). Accordingly, one of the most widely accepted conceptualizations of authentic leadership is the four dimensional model of Walumbwa et al. (2008). Drawing on Harter’s definition of authenticity (2002), the model emphasizes the congruence of one’s thoughts, feelings, preferences, and beliefs with one’s actions.

Authentic leaders are characterized as follows: they know their strengths and weaknesses and are highly aware of themselves (1. self-awareness); they openly show their emotions and their true self to their followers (2. relational transparency); they eagerly take others’ perspectives and views into account (3. balanced processing); and they consistently behave according to their own moral standards and values, i.e., they “act as they say” (4. internalized moral perspective) (Ilies et al., 2005; Neider & Schriesheim, 2011; Walumbwa et al., 2008). In addition, authentic leaders are self-confident, optimistic, reliable, and trustworthy. Leading by example, they foster followers’ strengths and potential, helping to create a healthy, transparent, and ethical work climate (Gardner, Avolio, Luthans, May, & Walumbwa, 2005; Ilies et al., 2005).

Indeed, the positive impact of authentic leadership in organizations is strongly evidenced in the literature. Recent research (Banks et al., 2016; Hoch et al., 2018; Schuh et al., 2017) indicates that authentic leadership has positive effects on followers’ psychological health and well-being, as well as their work-related attitudes (e.g., work engagement, commitment, job satisfaction, and interpersonal justice perceptions) and behaviors (e.g., task performance, creativity, and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB)). Given these benefits, it seems important to find methods for enhancing authentic leadership. In the present work, we propose mindfulness as an important predictor of and holistic means of improving authentic leadership.

Mindfulness

Scholars define mindfulness as a present-oriented state of awareness that is attentive, open-minded, and non-judgmental (Bishop et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2007). Mindfulness is an inherent human capacity that can be experienced by everyone, but it may vary in strength across situations and individuals (Pircher Verdorfer, 2016). In a mindful state, individuals direct attention to present-moment experiences, focusing on either external events (like the response of an interaction partner) or internal ones (such as thoughts, emotions, or physical sensations) while “allowing” these experiences to occur without judging their existence or content and without wanting to change them (Bishop et al., 2004; Dreyfus, 2011). The coupling of present-moment awareness and non-judgmental attitude allows one to “mentally step back”—also known as cognitive decentering (Bishop et al., 2004) or re-perceiving (Shapiro, Carlson, Astin, & Freedman, 2006)—and become less immersed in the emotional content of one’s thoughts. Instead, one is able to view those thoughts from a more distant perspective like an observer, thereby reducing emotional distress and ill-being (Kabat-Zinn, 2003).

Mindfulness has its roots in Buddhist tradition, but entered Western scholarly discourse in the late 1970s as a form of therapy (Kabat-Zinn, 1982, 2003). Its popularity has surged in the last 10 years (Van Dam et al., 2018), potentially due to the frenetic pace and associated stresses of the twenty-first century and the associated desires for a cure. Researchers have investigated mindfulness as a momentary state or quality of mind (state mindfulness), a dispositional variable (trait mindfulness), and a form of meditation that facilitates state and/or trait mindfulness (mindfulness interventions). Notably, all operationalizations of mindfulness are interrelated: The repeated experience of state mindfulness, facilitated through a mindfulness intervention, may lead to gradual changes in the level of trait mindfulness over time (Kiken, Garland, Bluth, Palsson, & Gaylord, 2015). Research has shown that mindfulness programs, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1982), benefit mental and physical health in clinical populations (Baer, 2003; Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004; Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010). Likewise, research indicates that mindfulness-based interventions are effective in reducing stress and anxiety while increasing well-being, attention, and emotion regulation in non-clinical populations (Eberth & Sedlmeier, 2012; Virgili, 2015).

In tandem with this larger trend, mindfulness has recently permeated the research agenda of work and organizational psychology (Allen et al., 2015; Eby et al., 2017; Glomb, Yang, Bono, & Duffy, 2011; Good et al., 2016; Hyland, Lee, & Mills, 2015; Lomas et al., 2017; Virgili, 2015). Several studies have focused on the role of employees’ general tendency to be mindful or their daily/situational experiences of mindfulness for important work and well-being outcomes, such as job satisfaction and performance (Dane & Brummel, 2014; Good et al., 2016; Hülsheger, Alberts, Feinholdt, & Lang, 2013; Hyland et al., 2015). In addition, mindfulness interventions have been adjusted to the work context in order to accommodate workers’ busy schedules, resulting in interventions that are usually short-term (e.g., 2–4 weeks), low-dose (5–10 min of practice per day), and self-administered (e.g., by using training booklets and audio files) (e.g., Hülsheger, Feinholdt, & Nübold, 2015). Such interventions have been shown to enhance employees’ level of mindfulness and emotion regulation at work (Hülsheger et al., 2013), reduce perceived stress and work-related rumination and fatigue (Klatt, Buckworth, & Malarkey, 2009; Querstret, Cropley, & Fife-Schaw, 2017), and help employees to psychologically detach from work and increase work-life balance (Michel, Bosch, & Rexroth, 2014).

Overview of Studies and Hypotheses

We tested the idea that mindfulness benefits authentic leadership in two studies, using different operationalizations of mindfulness (i.e., trait mindfulness and a mindfulness intervention) and authentic leadership (i.e., follower-rated and/or leader-rated). Study 1 is a cross-sectional multi-source field study, in which we examined the relationship between leaders’ trait mindfulness and follower-rated authentic leadership (H1a). Study 2 is a multi-source field experiment with pre-post measurements, which had three objectives: First, we sought to replicate the results of study 1 (leaders’ trait mindfulness and follower-rated authentic leadership; H1a) and test whether leaders’ trait mindfulness is also related to leader-rated authentic leadership (H1b). Second and most importantly, we tested the causal effect of a mindfulness intervention on both follower- and leader-rated authentic leadership (H2a and H2b), as well as the mediating effect of leaders’ trait mindfulness on these perceptions (H3a and H3b). Third and finally, we sought to test whether the mindfulness intervention had a positive effect on followers’ job satisfaction (H4a) and interpersonal justice perceptions (H4b) via authentic leadership as rated by followers.

Leaders’ Trait Mindfulness and Authentic Leadership

A key pre-requisite for authentic leadership is that leaders are aware of and embrace their true self: their fundamental values, needs, strengths, and weaknesses. It is this awareness that enables meaningful and authentic relationships with followers, and mindfulness may be an important means of promoting it. Highlighting the close conceptual link between mindfulness and authentic leadership, Reb et al. (2015) argued that “mindfulness, either as a skill, trait, or a cultivated practice, may facilitate authentic leadership” and “mindfulness practice can be considered as an avenue to develop authentic leader behavior” (p. 273).

A study by Leroy, Anseel, Dimitrova, and Sels (2013) provided preliminary evidence that the non-judgmental awareness of one’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors facilitated through mindfulness promotes greater awareness of one’s true self. The authors showed that trait mindfulness is related to work engagement via authentic functioning, the operation of one’s core or true self in one’s daily enterprise (Kernis, 2003, p. 13). Additional work by Baron (2012, 2016), which focused on the effects of extensive leader action learning programs, showed that leaders’ trait mindfulness was cross-sectionally related to their ratings of their authentic leadership behavior. In study 1, we follow these theoretical ideas (Reb et al., 2015) and initial findings (Baron, 2012, 2016; Leroy et al., 2013) by investigating the relation between leaders’ trait mindfulness and followers’ perceptions of their leaders’ authentic leadership. In the following, we will describe the relations more specifically.

Awareness is a key ingredient of mindfulness and a pre-requisite to authentic leadership (Gardner et al., 2005; Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Shapiro et al., 2006). Mindfulness may help to create a higher self-awareness in leaders, that is, awareness of one’s values, emotions, identity, and motives by paying more attention to and observing one’s thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations in a receptive and open way (Bishop et al., 2004; Shapiro et al., 2006). This heightened awareness allows leaders to see more clearly who they really are and what they really want (Gardner et al., 2005; Kinsler, 2014). In that sense, mindfulness may function as a “window into the self” that allows for greater clarity and self-awareness (Kinsler, 2014). In addition, as mindfulness entails simply observing what is happening without further judgment, it may be easier for leaders to more objectively perceive their personal characteristics, and particularly their weaknesses, with higher self-confidence and lower emotional resistance or anxiety (Brown & Ryan, 2003). For example, an attentive, non-judgmental attitude would allow a less charismatic leader to identify and embrace other inner qualities instead of feeling anxious and defensive about his/her shortcomings. Accordingly, empirical research has documented that mindfulness is related to greater self-esteem, less social anxiety, and greater self-compassion (Neff, 2003; Shapiro, Brown, & Biegel, 2007). As noted by Gardner et al. (2005), authentic leaders are aware of their emotions and are not afraid to experience them or display them to followers (when appropriate).

The second component of authentic leadership is relational transparency, which refers to the leader’s efforts to build a trustworthy relationship with his or her followers (e.g., Gardner et al., 2005; Ilies et al., 2005). Rather than play the role of an ever-confident leader without flaws, authentic leaders may leverage their higher awareness and acceptance of their strengths and weaknesses through a non-judgmental and self-compassionate attitude, in order to communicate more openly with their followers and show them who they really are (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Gardner et al., 2005). A higher attention to and receptive awareness of present-moment experiences is also a key driver of empathy and concern for others (Shapiro, Wang, & Peltason, 2015), which may increase leaders’ understanding for, and compassionate response to, their followers’ concerns and weaknesses. On this point, several studies have confirmed that both trait mindfulness and mindfulness training correlate with higher empathy and compassion (Beitel, Ferrer, & Cecero, 2005; Condon, Desbordes, Miller, & DeSteno, 2013; Dekeyser, Raes, Leijssen, Leysen, & Dewulf, 2008; Shapiro, Schwartz, & Bonner, 1998). In addition, empirical studies support the notion that mindfulness increases one’s attentiveness towards other people’s needs, and thereby improves relationships, mainly by encouraging higher-quality communication and sustained attention with interaction partners (Barnes, Brown, Krusemark, Campbell, & Rogge, 2007; Wachs & Cordova, 2007). Moreover, mindfulness can promote leaders’ self-regulation by inclining them to mentally step back (cognitive decentering; Bishop et al., 2004), which helps them to regulate and express their emotions appropriately and effectively. Accordingly, research has shown that people with high levels of mindfulness have reduced emotional reactions during conflicts (Barnes et al., 2007) and exhibit less hostility (Saavedra, Chapman, & Rogge, 2010) and anger (Wachs & Cordova, 2007).

The third component of authentic leadership is balanced processing. By adopting an attentive and non-judgmental attitude, leaders can be more receptive and attentive to information that they may not usually consider, giving them a more accurate perception of reality (Brown et al., 2007; Shapiro et al., 2006). Because mindfulness incorporates an open-minded, curious, and non-judgmental attitude towards internal and external experiences, it may enhance information processing (Brown et al., 2007). By just observing what is happening, without prematurely evaluating it, leaders may be better able to take different opinions and perspectives into account and to analyze relevant information in a more objective, less ego-involved, and less biased way (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Kernis & Goldman, 2006; Niemiec, Ryan, & Brown, 2008). Thus, before making important decisions, authentic leaders are able to balance and evaluate information from different sources in a more adequate way and can thereby better react to the requirements of the situation (Gardner et al., 2005). Relatedly, mindfulness may also promote self-regulatory processes in leaders, limiting automatic responses or overreactions while enhancing independent and conscious information processing as well as autonomous behavior (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Brown et al., 2007). For example, through an attentive and non-judgmental attitude, a leader may be better able to calmly listen to subordinates’ critiques without being personally offended. Instead, he/she might be better able to understand their underlying need for being seen and heard and can make more informed choices. An experimental study by Wenk-Sormaz (2005) confirmed that mindfulness meditation leads to a reduction in habitual responding, which can then open a space for individuals to actually choose how to act (Brown et al., 2007).

The last major component of authentic leadership is an internalized moral perspective: an integrated form of self-regulation guided by internal standards and values. Mindfulness leads to a heightened awareness of what one wants and what really matters in one’s life, thereby supporting leaders in the process of value clarification and in acting in congruence with their convictions (Shapiro et al., 2006). Empirical studies have confirmed that mindfulness meditation is associated with value clarification and purpose, and in turn with lower anxiety and higher perceptions of control (Carmody, Baer, Lykins, & Olendzki, 2009; Jacobs et al., 2011). Authentic leaders are aware of who they are and what matters to them, and they behave according to this knowledge (Gardner et al., 2005; Ilies et al., 2005). Further, as mindfulness increases the ability to mentally step back and to regulate one’s emotions and behaviors (Brown et al., 2007; Shapiro et al., 2006), leaders are better able to take guidance from their personal values rather than external pressures and norms (Gardner et al., 2005; Ilies et al., 2005; Neider & Schriesheim, 2011; Walumbwa et al., 2008). For example, through a present-centered awareness, a leader may be better able to enforce his/her values (e.g., to strive for excellence) and resist the external pressures to produce results faster. A study by Ruedy and Schweitzer (2010) confirmed this point, finding that individuals high in mindfulness were more likely to value upholding ethical standards and making ethical decisions than individuals low in mindfulness, both of which are integral parts of authentic leadership (Gardner et al., 2005, 2011).

In sum, we propose that:

-

Hypothesis 1a.

Leaders’ trait mindfulness will be positively related to follower-rated authentic leadership.

Study 1

Sample and Procedure Study 1

In Study 1, our goal was to test the cross-sectional relationship between a leader’s trait mindfulness and followers’ ratings of authentic leadership. This study was part of a larger data collection effort on leader mental health (Van Quaquebeke 2016), but used different variables. We recruited participants in Germany via Lightspeed GMI, a company providing high-quality data collection services. Research has shown that participants recruited via such services are equally representative of the population as standard Internet samples and that the obtained data are at least as reliable as those obtained via traditional methods (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Paolacci & Chandler, 2014). GMI panelists are intensively pre-screened and frequently asked to update their demographic, employment, and consumer information in order to allow for high-quality profiled panels (such as those that include participants with leadership responsibility). We only approached people who were marked as potential leaders in the GMI database. They were individually informed about the study and gave their consent for participation. Afterward, they were invited to fill in the leader questionnaire and asked to forward a second questionnaire to one of their employees with whom they interact on a regular basis. The topic of the study was intentionally kept vague, described simply as assessing the quality of “leader-follower relationships”.

We were able to match follower data with 221 leaders (out of a total of 1,062 participants who took the survey). However, 12 followers (and their paired leaders) had to be excluded due to poor data quality (extremely unreasonably short time for responding to the survey and incorrect answers on Instructional Manipulation Checks (IMCs); Oppenheimer, Meyvis, & Davidenko, 2009). In total, this led to a response rate of ca. 20%. The leader-follower dyads (N = 209) stemmed from a variety of sectors: The largest percentages worked in the wholesale and retail industry (13.9%), the service industry (12%), the IT/electronic sector (7.2%), and for a government agency, court or ministry (6.7%).

Females comprised 30.1% of the leader sample. On average, leaders were 43.21 (SD = 8.76) years old, had an organizational tenure of 13 years (SD = 8.98), and had 22.40 (SD = 9.59) years of working experience. The follower sample featured 51.2% females. On average, followers were 37.08 (SD = 10.10) years old, had 16.75 (SD = 10.33) years of working experience, and had been working with their leader for 5.24 years (SD = 5.23), ranging from several months to a maximum of 40 years.

Measures Study 1

Leaders were asked to indicate their level of trait mindfulness and have one respective follower judge his or her authentic leadership behavior. Leaders’ mindfulness was measured with the 15-item Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) by Brown and Ryan (2003). A sample item is “I find myself doing things without paying attention” (reversed). Authentic leadership was measured with the 14-item Authentic Leadership Inventory (ALI) by Neider and Schriesheim (2011). A sample item of this scale is “My leader shows consistency between his/her beliefs and actions.” Scales had to be answered on a 6-point and 5-point Likert-type scale, respectively.

Results Study 1

Table 1 depicts the means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and intercorrelations of the variables in study 1. The internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alpha) of the mindfulness and authentic leadership scale can both be considered good (α > .90). None of the demographic variables were significantly correlated with leader mindfulness or authentic leadership.

To test Hypothesis 1a, which proposes that followers perceive more authentic leadership from leaders with high levels of trait mindfulness, we inspected the zero-order correlation between leader trait mindfulness and follower-rated authentic leadership. Table 1 shows that the correlation was small to moderate in size and statistically significant (r = .22, p < .01), confirming Hypothesis 1a.

Brief Discussion Study 1

Despite study 1’s valuable first insights into the relationship between trait mindfulness and authentic leadership as perceived by followers, there are some open questions. First, previous research underscores that leaders and followers can vary in their perceptions of leadership behaviors (Atwater & Yammarino, 1992; Olsson, 2017). These differences may be substantial, as correlations between leader and follower ratings of leadership behavior have been found to be rather low and non-significant (Atwater & Yammarino, 1992). Previous studies on authentic leadership have primarily relied on followers to rate the authenticity of leadership (Banks et al., 2016), while scholars have recently started to emphasize the importance of collecting data from both followers and leaders (Cooper et al., 2005). It still remains a point of debate whether authentic leaders are genuinely authentic if they judge themselves to be or if they are perceived as such by followers (e.g., Cooper et al., 2005; Harvey, Martinko, & Gardner, 2006; Shamir & Eilam, 2005). Teasing apart leaders’ and followers’ perceptions is essential in order to determine whether a behavioral or attributional perspective of authentic leadership is more valid (Cooper et al., 2005). Thus, in order to fully capture and understand the role of mindfulness for authentic leadership, it would be desirable to consider both followers’ and leaders’ perspectives of authentic leadership simultaneously.

Second, while establishing a cross-sectional relationship between trait mindfulness and authentic leadership was an important first step, it does not allow us to draw causal inferences. Although our theoretical arguments suggest that mindfulness should lead to more authentic leadership, and that follower perceptions of authentic leadership are unlikely to spur higher leader trait mindfulness or perceptions thereof, we cannot rule out such alternative explanations based on the cross-sectional findings. In addition, this cross-sectional relationship does not provide us with any insights on the potential degree and nature of authentic leadership’s malleability.

The Effect of a Mindfulness Intervention and Authentic Leadership

In study 2, we addressed these open questions by (a) considering leader and follower perceptions of authentic leadership simultaneously and (b) conducting a field experiment that manipulated leader trait mindfulness. Based on previous studies investigating pre-post intervention changes in trait mindfulness across a number of weeks (e.g., Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Kiken et al., 2015), we expected to see changes in leaders’ trait mindfulness (i.e., the general tendency to be mindful in their daily life) via the repeated experience of mindful states facilitated through the intervention. Specifically, we used a pre-/post-test, waitlist control group design to study the effect of a 30-day, app-based mindfulness intervention on leader- and follower-rated authentic leadership.

The general goal of guided meditation exercises is to help participants focus their attention on present-moment experiences in a non-judgmental way (Kabat-Zinn, 1982). This is typically done by instructing participants to hone in on their breath, bodily sensations, thoughts, or feelings, and then simply observe rather than evaluate what they experience. Through guided instructions, individuals are encouraged to become aware of their thoughts and emotions without ruminating or directly reacting upon them. Over time, these guided exercises can help individuals increase their daily awareness of habitual patterns of thinking, reacting, and feeling. Thus, an essential aim of mindfulness training is not only to foster present-moment awareness and a non-judgmental attitude towards one’s experiences during meditation, but also to encourage informal forms of mindfulness in daily life.

For example, through repeated formal practice of focusing one’s attention on different momentary experiences and by training to bring back one’s attention when one’s mind wanders off, leaders may be better able to direct their attention when interacting with their followers. In doing so, they can become better listeners who consider followers’ perspectives, thereby improving balanced processing (Brown et al., 2007; Gardner et al., 2011). Likewise, by accepting experiences as they are and resisting the impulse to criticize or blame oneself for thoughts or feelings while meditating, leaders may learn to be more kind towards oneself and to deal with positive and negative thoughts and feelings with acceptance and compassion. This may, in turn, benefit leaders’ daily leadership behavior, as they will be more aware of their automatic judgment processes and better able to replace them with a more accepting and compassionate attitude towards themselves and others, thereby increasing self-insight, self-acceptance, and relational transparency (Gardner et al., 2011; Kabat-Zinn, 1982; Shapiro et al., 2006).

Despite growing interest in the role of mindfulness for leadership, high-quality research on the effectiveness of mindfulness trainings in the context of leadership is still scarce (Donaldson-Feilder et al., 2018; Good et al., 2016). While both general leadership interventions (Avolio, Reichard, Hannah, Walumbwa, & Chan, 2009; Burke & Day, 1986) and mindfulness interventions (Donaldson-Feilder et al., 2018) have been shown to improve aspects of leadership behavior and leader well-being, only a few studies (Baron, 2012, 2016; Wasylkiw, Holton, Azar, & Cook, 2015) have particularly addressed the benefits of mindfulness for authentic leadership. However, these studies differ from the present study in significant ways. The study by Baron (2012, 2016) tested an extensive 3-year action learning program with a multitude of elements (of which mindfulness was one small part), while the pilot study by Wasylkiw et al. (2015) investigated the effect of a meditation weekend retreat. Although both studies used a control group design, participants were not randomly assigned to conditions, rendering causal conclusions invalid; in addition, the pilot study was heavily underpowered (Wasylkiw et al., 2015). In the present study, we not only tried to ensure methodological rigor by conducting an a priori power analysis and using a randomized controlled design, but we also aimed for clearer conclusions regarding the actual content and mechanism responsible for a potential effect. Specifically, in order to make valid inferences about the precise elements and mechanism of a potentially successful intervention, we used a pure and highly focused mindfulness intervention without additional elements, and tested whether leaders’ increase in mindfulness is actually the specific underlying mechanism explaining the intervention’s potential effect on authentic leadership (see Donaldson-Feilder et al., 2018).

In summary, study 2 sought to replicate and extend the findings of study 1 regarding the relationship between leaders’ trait mindfulness and follower-rated authentic leadership. To this end, we tested if the trait mindfulness–authentic leadership relation also holds true for leader ratings of authentic leadership. However, our main focus was testing whether the mindfulness intervention may improve authentic leadership as perceived by both, followers and leaders themselves, via an increase in leaders’ mindfulness. Thus, we propose:

-

Hypothesis 1.

Leaders’ trait mindfulness at t1 (i.e., prior to the intervention) will be positively related to authentic leadership at t1 as perceived by (a) followers and (b) leaders.

-

Hypothesis 2.

The mindfulness intervention will have a positive effect on authentic leadership at t2 (i.e., after the intervention) as perceived by (a) followers and (b) leaders (while controlling for authentic leadership at t1).

-

Hypothesis 3.

The mindfulness intervention will have a positive effect on authentic leadership as perceived by (a) followers and (b) leaders at t2vialeaders’ trait mindfulness at t2 (while controlling for mindfulness at t1).

The Effect of a Mindfulness Intervention on Followers’ Job Attitudes

Another question is whether the effects of the mindfulness intervention are confined to authentic leadership behavior or actually extend to more distal follower outcomes. In the present study, we focused on two important work attitudes of followers as outcomes of the mindfulness intervention for leaders. Specifically, we focused on followers’ job satisfaction—the most widely studied attitude towards work—and followers’ interpersonal justice perceptions—a more specific outcome of authentic leadership behavior. Authentic leadership theory has repeatedly highlighted both factors as outcomes of an authentic leader-follower relationship (Gardner et al., 2005; Gardner et al., 2011; Luthans et al., 2001; Walumbwa et al., 2008).

The mindfulness intervention should enable leaders to better communicate and act upon their true values and goals, thereby improving their trustworthiness and relationship with followers. By cultivating an open attitude that takes followers’ perspectives into account, leaders should be better able to come to balanced decisions (Gardner et al., 2005), thus, enhancing followers satisfaction with such processes. Indeed, empirical research underscores that followers derive greater job satisfaction, when being led by an authentic (Neider & Schriesheim, 2011) and mindful leader (Reb, Narayanan, & Chaturvedi, 2014).

A similar relationship seems to hold for followers’ justice perceptions. The mindfulness intervention should enable leaders to engage in more objective and unbiased information processing, thereby increasing followers’ perceptions of fairness (Greenberg, 1993). Specifically, when subordinates are shown empathic concern for their needs and openness to their opinions by their leaders, they are more likely to feel valued and respected, which increases their sense of interpersonal justice (Schuh et al., 2017). Accordingly, studies have found a positive relationship between followers’ justice perceptions and both authentic leadership (Kiersch & Byrne, 2015; Li, Yu, Yang, Qi, & Fu, 2014) and leaders’ trait mindfulness (Schuh et al., 2017).

In sum, we test whether the mindfulness intervention results in higher follower ratings of authentic leadership, and whether those perceptions then translate into more positive job attitudes (i.e., job satisfaction and interpersonal justice perceptions). Taken together, we propose:

-

Hypothesis 4.

The mindfulness intervention will have a positive effect on followers’ (a) job satisfaction and (b) interpersonal justice perceptions at t2viaauthentic leadership as perceived by followers at t2 (while controlling for authentic leadership at t1).

Study 2

Power Analysis Study 2

We conducted a number of a priori power analyses in order to detect the appropriate sample size for the intervention study. Following the recommendations of Perugini, Gallucci, and Costantini (2018), we considered different scenarios by varying the effect size, alpha level, and desirable power levels. We derived our effect sizes from two meta-analytic findings: The first, covering the effect of mindfulness interventions in the work context (Virgili, 2015), indicated an overall effect size of g = .68 for both within-group (pre–post) and between-group comparisons. The second, covering the effect of leadership interventions (Avolio et al., 2009), yielded an effect size of d = .62 for leadership interventions in the field (as compared to manipulations in the lab). For all analyses, we used the tool G*power (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). The estimated sample sizes range between 55 and 112 (with a mean of 81 and a median of 80), based on our meta-analytically derived effect sizes (Avolio et al., 2009; Virgili, 2015), alpha estimates of .05 or .10 (one-sided testing due to directional hypotheses), and power estimates of .90 or .80. When using the standard (and more conservative) alpha level of .05, alongside a standard power level of .80 as advised by Cohen (1965) and others (see Bakker, Hartgerink, Wicherts, & van der Maas, 2016), we concluded that a sample size between 70 and 84 leader-follower dyads should suffice for our study.

Sample Study 2

We recruited dyads via professional and social media sites such as LinkedIn, by directly approaching organizations and companies, and by leveraging the research assistants’ personal networks. Depending on the respective strategy, we first approached leaders either personally or in writing (e.g., emails or posts). Leaders were encouraged to send the research team an email if they were interested in participating. Those who replied were then thoroughly informed about the study’s procedure, invited to respond to the first questionnaire prior to the intervention (time 1), provided with further condition-specific instructions (e.g., for using the code to access the app’s mindfulness intervention), and invited to respond to the second questionnaire after the intervention (time 2). At both times, leaders were instructed to forward the follower questionnaire to their subordinate. Leaders did not receive any incentive, besides the free 30-day access to the mindfulness app and a summary report of the results. We did not apply any exclusion criteria outside of participants having to hold a leadership position and possess advanced English understanding.

At time 1, 210 leaders showed initial interest in our study and looked at the online survey. Out of these 210 leaders, 30 were excluded for either not answering at all or dropping out after answering only a few items. In addition, due to a technical problem, seven leaders needed to be excluded from the study as they were assigned the same identification number and could not be matched correctly to their respective follower. This resulted in a final sample of 173 leaders filling in the pre-intervention questionnaire: 93 in the experimental group and 80 in the control group. Initially, 138 followers showed interest in the study, 125 of which answered the pre-intervention questionnaire properly, meaning that 13 cases were excluded due to non-response.

At time 2, 109 leaders used the link for the second survey, but five cases were excluded because of non-response, resulting in a sample of 104 leaders for time 2. In the follower sample, 92 used the link for the second survey, but five were excluded because of non-response, leaving 87 followers at time 2. Because differing amounts of leaders and followers completed the pre- or post-questionnaire, we tested the different hypotheses with different sample sizes (e.g., 173 leaders to test the relationship between leaders’ trait mindfulness and self-rated authentic leadership at time 1, but 99 to test the effect of the mindfulness intervention on leaders’ change in trait mindfulness). We obtained informed consent from all participants included in the study.

Leader-follower dyads came from a number of different nations, with the highest concentrations hailing from Germany (45.8%), Serbia (9.0%), the USA (8.4%), the Netherlands (8.4%), and Austria (6.0%). Leaders and their followers worked in a variety of branches. The largest percentages worked in the human health and social work sector (15%), in the manufacturing area (12.1%), in other service activities (11.6%), in the financial and insurance sector (8.1%), and in areas such as public administration and defense, real estate, accommodation and food services, construction, or arts entertainment and recreation (1–3% respectively).

The leader sample consisted of 40.1% females (with one person not providing any gender information). Leaders had a mean age of 41.24 years (SD = 10.27), were part of the organization for 9.46 years on average (SD = 8.79), and had 18.89 years of working experience on average (SD = 11.00). The majority of leaders had completed a master’s degree or diploma (49.1%). Fifteen percent indicated a bachelor’s degree/pre-diploma, 9.2% an advanced technical college certificate, and 9.2% a PhD as their highest educational degree. Six percent stated that secondary education was their highest educational degree, compared with 5.2% for a baccalaureate, and 0.6% for junior high school. Ten participants (5.8%) answered that their highest degree was not included in the mentioned selection.

Fifty-two percent of the followers were female. Followers had a mean age of 33.68 years (SD = 10.01), an average tenure of 5.43 years (SD = 5.89), and average working experience of 12.06 years (SD = 10.30). In the follower sample, 39.2% indicated that they held a master’s degree or diploma, 27.2% had a bachelor’s degree, 8.0% had a secondary education, 8.0% completed their baccalaureate, 4.8% held an advanced technical college degree, and 2.4% respectively completed junior high school or their PhD.

Design and Procedure Study 2

Study 2 was a multi-source field experiment where participants were randomly assigned to the intervention group or the waitlist control group. The study variables were assessed before (time 1) and after the 4-week intervention (time 2) in order to investigate changes in leader mindfulness and (both follower- and leader-rated) authentic leadership. Leaders in both groups were instructed to forward a personalized link, generated inside their own questionnaire, to one of their subordinates so that we could obtain ratings on their behavior from an additional source. After completing the pre-intervention questionnaire at time 1, leaders in the intervention group received further information about the web-based mindfulness intervention and were instructed to use a personal voucher code included in the email to get the free 30-day access to the exercises. After 30 days at time 2, leaders from both the experimental and control group received the post-intervention questionnaire and were again instructed to forward the follower questionnaire to their subordinate. Once data collection at time 2 was complete, leaders in the waitlist control group, as well as followers in both groups, were offered the option to utilize the free 30-day access to the web-based mindfulness training. Finally, all participants were debriefed and received a summary of the study findings via email. The study was approved by the local ethical review board (ECP_150 03_08_2014_A2 OZL).

The Mindfulness Intervention

The intervention consisted of a 30-day, self-guided, app-based mindfulness training, consisting of guided mindfulness meditation exercises developed by Headspace, Inc. (www.headspace.com). Previous studies have documented the validity of the Headspace app as a means of delivering mindfulness interventions, showing that it has positive effects on job control and well-being (Bostock & Steptoe, 2013), positive affect and depressive symptoms (Howells, Ivtzan, & Eiroa-Orosa, 2016), and compassionate behavior (Lim, Condon, & DeSteno, 2015). Participants could use either a smartphone or computer to download the app. Leaders could then practice mindfulness autonomously for the next 30 days, following a sequence of 10-min daily guided mindfulness meditation exercises. The exercises were based on typical mindfulness meditation practices, such as those used in MBSR programs (Kabat-Zinn, 1982), and anchored participants’ attention to present-moment experiences such as their breath, bodily sensations, cognitions, and emotions. The exercises promoted an open and accepting state of mind by encouraging participants to simply notice thoughts, emotions, and sensations with an attitude of curiosity, instead of trying to alter, ignore, or suppress them. Thus, whenever participants’ mind wandered off, they were reminded to gently return their attention to the present moment without blaming themselves. The app’s exercises were clustered into different themes, beginning with a series on foundations of mindfulness meditation. After completing the initial series, participants could unlock further series on additional themes, such as health, relationships, and performance. In sum, all exercises aimed to cultivate an open and non-judgmental state of mind that focused on the present without ruminating about the past or worrying about the future.

Measures Study 2

All scales (leader mindfulness, follower-rated authentic leadership, and leader-rated authentic leadership) were measured prior to and after the 30-day mindfulness intervention. Items were presented in English and had to be answered on 5-point Likert scales. We collected the demographic information of both leaders and followers in the pre-intervention questionnaire at time 1. As in study 1, leaders’ mindfulness was measured with the 15-item Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) by Brown and Ryan (2003), while authentic leadership was measured with the 14-item Authentic Leadership Inventory (ALI) by (Neider & Schriesheim, 2011). Leaders had to rate the items with regard to their own leadership behavior, whereas followers were asked to rate the behavior of their supervisor. Followers’ job satisfaction was assessed with five items from a short version of the Brayfield Rothe scale (Brayfield & Rothe, 1951), which past research has shown to be reliable and valid (Judge, Bono, & Locke, 2000). A sample item is “Most days I am enthusiastic about my work”. Followers’ interpersonal justice perceptions were assessed with four items from the interpersonal justice scale of Colquitt’s (2001) organizational justice questionnaire. A sample item is “To what extent has he/she treated you with respect?”

Analytical Approach Study 2

According to Bodner and Bliese (2018), two-wave randomized pre-test–post-test control group designs can theoretically be analyzed using three different statistical approaches (post-test only, analysis of covariance [ANCOVA], and difference in mean change), which differ in their precision and power to detect intervention effects. We chose to use regression analyses, controlling for outcomes at T1 to test the main effect of the intervention on leaders’ trait mindfulness (manipulation check) and on leader- and follower-rated authentic leadership (H2a and H2b). As argued by Bodner and Bliese (2018), this analytical procedure corresponds to an ANCOVA model and is more powerful at detecting intervention effects than the other two approaches. Meanwhile, we used the PROCESS macro by Hayes (2017) to test the indirect effects of the intervention on follower- and leader-rated authentic leadership via leaders’ mindfulness (H3a and H3b), and on followers’ job satisfaction and justice perceptions via authentic leadership (H4a and H4b). To that end, we used group membership (intervention vs. waitlist control group) as a predictor and controlled for the outcome variable at time 1.

Results Study 2

Descriptives

Table 2 depicts the means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and intercorrelations between study variables. The correlations between time 1 and 2 leader mindfulness (r = .69, p < .001; N = 99), as well as between time 1 and 2 authentic leadership as rated by leaders (r = .66, p < .001; N = 99) and by followers (r = .62, p < .001; N = 86) indicate moderate to high levels of stability. Followers’ job satisfaction (r = .63, p < .001; N = 86) and interpersonal justice perceptions (r = .68, p < .001; N = 86) were also moderately stable. Leader gender was significantly related to authentic leadership ratings among both followers and leaders at time 2. Compared to men, women judged themselves as having higher levels of authentic leadership (r = −.26, p < .05; N = 99), and were also rated by their followers as showing higher levels of authentic leadership (r = −.21, p < .10; N = 84), after the intervention. Leaders’ age was significantly related to leaders’ level of trait mindfulness at time 1 (r = .34, p < .001; N = 173) and time 2 (r = .26, p < .05; N = 99), as well as with authentic leadership (r = .23, p < .05; N = 118) and job satisfaction as rated by their followers at time 1 (r = .23, p < .05; N = 117). Followers’ age was significantly related to their job satisfaction at time 1 (r = .26, p < .01; N = 124) and time 2 (r = .36, p < .01; N = 86).

Dropout Analysis

Following the recommendation by Bell, Kenward, Fairclough, and Horton (2013), we tested whether the two groups (completers and dropouts) significantly differed in a number of baseline measures. The results from a set of one-way ANOVAs showed that completers and dropouts did not differ in any of the demographic variables (e.g., age, tenure) or focal constructs (authentic leadership, mindfulness). In order to test whether participants withdrew from the study for reasons related to the intervention, we conducted a logistic regression analysis. Results showed that participants in the intervention group (47% dropouts) were not more likely to dropout from the study than those in the control group (41% dropouts) (standardized odds ratio = .771, p = .39). The results suggest that the data in our case are “missing completely at random”, that is, due to reasons that are unrelated to the study (Bell et al., 2013).

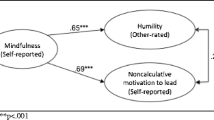

Relation of leader trait mindfulness with follower and leader-rated authentic leadership

To test Hypothesis 1a, we tested whether the relationship between leaders’ trait mindfulness and followers’ perceptions of authentic leadership was significant at the baseline measurement (i.e., at time 1). This was the case (r = .21, p < .05, N = 118), thereby confirming Hypothesis 1a and replicating the findings of study 1. Leaders’ trait mindfulness level and their own rating of their authentic leadership behavior also significantly correlated at time 1 (r = .35, p < .001, N = 173), thereby confirming Hypothesis 1b. This pattern was confirmed at time 2: Followers’ perceptions of authentic leadership were marginally related to leaders’ trait mindfulness at time 2 (r = .19, p = .09, N = 85) while leaders’ same perceptions were significantly related to leader’s trait mindfulness at time 2 (r = .35, p < .001, N = 104). In line with these results, the leader and follower ratings of authentic leadership at time 1 (r = .29, p < .01, N = 118) and at time 2 (r = .23, p < .05, N = 85) were significantly related.

Manipulation Check

Following the recommendation from Donaldson-Feilder et al. (2018) and a number of prior mindfulness intervention studies (see e.g., Hafenbrack, Kinias, & Barsade, 2014; Hülsheger et al., 2015; Michel et al., 2014), we tested whether the mindfulness intervention was actually effective (i.e., led to an increase in mindfulness). In contrast to typical manipulation checks, we did not assess whether participants in the experimental condition actually fully adhered to the intervention and practiced on a regular basis. Instead, we followed an intent-to-treat (ITT) approach, which does not pay attention to noncompliance or protocol deviations (Gupta, 2011). As summarized by Gupta (2011), an ITT analysis has the benefit of maintaining the prognostic balance generated by the original randomization, a conservative estimation of the intervention’s effectiveness by including non-compliers, and a preservation of the sample size in order to safeguard statistical power. Thus, an ITT analysis provides more unbiased treatment effects and a more realistic account of applied practice where training participants do not always follow instructions.

First, to ensure pre-treatment equivalence between the experimental and control groups, we ran a one-way ANOVA to compare the pre-experimental levels of mindfulness and authentic leadership for the two groups. Despite randomization, the means of mindfulness in the experimental and control groups were significantly different at time 1 (F(1,171) = 5.781, p < .05), indicating pre-experimental differences in mindfulness across the two groups. In contrast, the authentic leadership ratings of leaders (F(1,171) = .000, p = .99) and followers (F(1,118) = .017, p = .90) did not differ prior to the intervention. After the intervention (at time 2), groups did not significantly differ in mindfulness (F(1,102) = .576, p = .450), while there were marginal differences in leader ratings (F(1,102) =3.821, p = .053) and follower ratings of authentic leadership (F(1,85) =3.880, p = .052). Table 3 below reports the means, standard deviations and sample sizes.

To determine the effectiveness of the mindfulness intervention, we tested whether group membership predicted leaders’ trait mindfulness at time 2 while controlling for mindfulness at time 1. When controlling for pre-intervention scores, the results of the regression analysis indicated that leaders in the experimental group had higher levels of trait mindfulness at time 2 compared to the control group (β = .30, p < .001). Taken together, these findings support that the 4-week mindfulness intervention for leaders had the intended effect on leaders’ trait mindfulness.

Effect of the Mindfulness Intervention on Authentic Leadership

To test our second Hypothesis (H2a and H2b), we analyzed whether the dummy coded intervention variable significantly predicted authentic leadership at time 2 while controlling for authentic leadership at time 1. When controlling for pre-test scores, the findings of the regression analysis indicated that the mindfulness intervention predicted significantly higher levels of both leader-rated (β = .18, p < .05) and follower-rated authentic leadership at time 2 (β = .17, p < .05). The effects were of small to medium size (d = .47 and d = .44), respectively. In sum, our findings confirm both Hypotheses 2a and 2b.

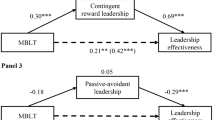

Effect of the intervention on authentic leadership via mindfulness

Next, we tested the indirect effect of the intervention on follower- and leader-rated authentic leadership (H3a and H3b) via leaders’ trait mindfulness. The indirect effect of the mindfulness intervention on follower-rated authentic leadership at time 2 via leaders’ trait mindfulness at time 2 (while controlling for trait mindfulness at time 1) was not significant (estimate = .007; 95% CI [− .07; .10]). In contrast, we found a significant indirect effect of the intervention on leader-rated authentic leadership via leader trait mindfulness at time 2 (while controlling for trait mindfulness at time 1; estimate = .12; 95% CI [.03; .28]). Taken together, Hypothesis 3b was confirmed, while Hypothesis 3a was not.

Effect of the Intervention on Follower Attitudes via Authentic Leadership

Finally, we tested whether the mindfulness intervention had a positive effect on followers’ job satisfaction (H4a) and their interpersonal justice perceptions (H4b) via authentic leadership as perceived by followers. We defined group membership (intervention vs. waitlist control group) as the predictor, time 1 follower ratings of authentic leadership as the control, time 2 follower ratings of authentic leadership as the mediator, and followers’ time 2 job satisfaction and interpersonal justice perceptions as the outcome variables. Whereas the indirect effect of the mindfulness intervention on follower-rated job satisfaction at time 2 (estimate = .06; 95% CI [− .01; .18]) was not significant, the indirect effect of the intervention on followers’ perceptions of interpersonal justice at time 2 via follower-rated authentic leadership was significant (estimate = .05; 95% CI [.01; .14]). In sum, Hypothesis 4b was confirmed, whereas Hypothesis 4a was not.

Brief Discussion Study 2

Replicating the results of study 1, study 2 showed that followers perceive more authentic leadership behavior from leaders who possess high levels of trait mindfulness. Likewise, Study 2 uncovered a similar relation between leaders’ trait mindfulness and their own perceptions of their authentic leadership behavior. Thus, our findings advance our understanding of authentic leadership by delineating its “conceptual make up” from two different perspectives: leaders and followers. Both perspectives (one’s own perceptions of authenticity as well as the authenticity ascribed by others) seem to be valid for judgments of authentic leadership (Cooper et al., 2005).

Furthermore, study 2 tested the causal effect of a mindfulness training on authentic leadership and could support this relation for both leaders and followers’ perceptions of the leaders’ authentic leadership behavior. For leaders, we confirmed that mindfulness acts as an explanatory mechanism that translates the intervention’s effect into authentic leadership behaviors. For followers, this was not the case. While there was a significant direct effect of the intervention on follower-rated authentic leadership, this effect was not mediated by leader-rated mindfulness. In order to more fully understand this inconsistency in findings, future research may consider both leader- as well as follower-ratings of leader mindfulness.

Finally, study 2 confirmed that the intervention has an indirect effect on followers’ perceptions of interpersonal justice via authentic leadership; however, we did not find a similar effect on general job satisfaction. This may be explained by the fact that job satisfaction has a much broader scope and incorporates many aspects of one’s daily work life rather than just the interactions with one’s leader.

General Discussion

In two consecutive studies, a multi-source cross-sectional study and a multi-source field experiment, we identified leader mindfulness as an important antecedent of authentic leadership behavior in organizations. Leaders with high levels of trait mindfulness were more likely to show authentic leadership behaviors, as perceived by both themselves (study 2) and their followers (study 1 and 2). In addition, we determined that a short-term, low-dose mindfulness intervention serves as a valuable tool for enhancing leaders’ mindfulness and authentic leadership behavior (as perceived by both leaders and followers) in a cost- and time-efficient way (study 2). Our findings provide organizations with important insights on who to select for leadership positions in order to promote authentic leadership behaviors, as well as how to train those leaders for whom mindfulness and authentic leadership may not come naturally.

With regard to the literature on mindfulness in leadership, our study makes several important contributions: First, our study provides important initial evidence that mindfulness interventions delivered via an app are an effective and relatively cost efficient tool for cultivating authentic leadership. Our findings suggest that those aspects of authentic leadership that are empirically linked to mindfulness are indeed malleable and possible to train. Thus, in contrast to previous studies that focused on more stable dispositional characteristics as antecedents of authentic leadership (psychological capital, leader self-knowledge and self-consistency; Jensen & Luthans, 2006; Peus, Wesche, Streicher, Braun, & Frey, 2012), our study provides hope for the many people who are not natural-born leaders and could use support in developing their individual form of authentic leadership (Cooper et al., 2005). As authentic leadership is regarded as central to a number of value-based leadership behaviors (Ilies et al., 2005), mindfulness interventions may potentially influence a variety of behaviors simultaneously—and thus possibly play an important role for leadership trainings in general. Future studies should further explore the effect of mindfulness training on a variety of leadership behaviors, determining which ones benefit most from mindfulness practices and which ones act as important prerequisites for other behaviors. Likewise, as recommended by Davidson and Kaszniak (2015), future studies should compare the effect of mindfulness trainings against other proven effective interventions with regard to a specific outcome.

Second and more conceptually, by focusing on the enhancements initiated by mindfulness, our study helps to further clarify the nature and definition of authentic leadership. In a way, our findings address the recognized shortcomings of purely cognitive-behavioral-based approaches to leadership training (Boyatzis & McKee, 2005; George, 2010). Rather than focusing on a specific leadership style or way to communicate, like traditional methods, mindfulness interventions instead train a specific quality of mind or way of being. This entails a more holistic approach that enables individuals to discover, support, and act in congruence with their true self.

As leaders play a central role in organizations (Yukl, 2010) their mindfulness and authentic way of being may “trickle down” to different levels (Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, 2009); through social learning and exchange processes (Bandura, 1977; Blau, 2017), authentic leadership may eventually shape the whole culture of an organization. In this vein, leader mindfulness and authentic leadership could spur increases in follower mindfulness and authentic followership (e.g., Avolio & Reichard, 2008), and perhaps collective mindfulness and authentic organizations (Ryde & Sofianos, 2014; Sutcliffe, Vogus, & Dane, 2016). Future studies should longitudinally test such organization-wide developments and identify potential mechanisms, for example conversations or shared beliefs regarding organizing practices (Sutcliffe et al., 2016).

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the benefits of our multi-method approach, each study naturally has its limitations: As discussed above, study 1 featured a multi-source design and decent power, but is limited by its cross-sectional nature. Study 2 compensated for that weakness by adopting an experimental design through which we could draw causal inferences. By implementing random group assignment in combination with pre- and post-intervention measurements, our study responded to recent calls for more rigorous designs in mindfulness intervention studies (for critiques, see e.g., Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Donaldson-Feilder et al., 2018; Eby et al., 2017; Jamieson & Tuckey, 2017; Lomas et al., 2017).

However, study 2 also has limitations. Particularly, the use of a waitlist control group design may have led to demand characteristics, as participants in both groups were aware of their group assignment (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015). As Davidson and Kaszniak (2015) note, the usual remedy against demand characteristics—blinding participants—is simply not possible with meditation-based interventions that are compared against a waitlist control group. Thus, we agree with the authors who call for more advanced designs in mindfulness research, such as including an active control group in place of or even in addition to a passive one. When doing so, it is critically important to match or standardize several non-specific intervention characteristics, such as duration, amount of scheduled (daily) practice time, and instructor expertise (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015). Future studies could compare an experimental group using a mindfulness meditation app with an active control group using a brain training app (Lim et al., 2015), for example, thereby reducing demand effects. In addition, comparing our mindfulness training with another intervention designed to develop authentic leadership would also be desirable. However, the choice of an adequate active control group requires an existing body of viable alternatives. In clinical settings, it is common practice to compare a new treatment to the best or most cost-effective intervention out there, but in the field of authentic leadership, well-powered, randomized controlled trials do not exist yet. With our study, we hope to provide a first benchmark for future research that wants to uncover the best interventions for enhancing authentic leadership. Through such a comparison, future studies may further rule out demand effects and judge the relative utility and effectiveness of their intervention.

Furthermore, our findings indicate that a change in authentic leadership, resulting from the mindfulness intervention, influenced followers’ perception of interpersonal justice, but not their ratings of general job satisfaction. This suggests that fine-grained changes in leadership behavior may not directly affect followers’ evaluations of their general job satisfaction. Thus, it seems important that future studies consider the specificity of the outcome measures and their sensitivity to leadership behavior. For example, previous research did find a relation between authentic leadership and followers’ job satisfaction (e.g., Neider & Schriesheim, 2011)—at least when using job satisfaction measures that contain items directly referring to supervision (e.g., from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire; Weiss, Dawis, Lofquist, & England, 1967). In contrast, our job satisfaction survey (Brayfield & Rothe, 1951) referred to ratings of pleasantness, enjoyment, and enthusiasm regarding the job itself—features that are clearly affected by many more aspects than leadership alone. Future studies should focus their efforts on follower outcomes that are sensitive to changes in leaders’ mindfulness and authentic leadership, such as constructs that have a strong interaction focus. That said, theorising and operationalization of the concept of authentic leadership is also not at an end and will likely need further revision in order to more conclusively interpret effects (Alvesson & Einola, 2019).

Finally, future studies may further investigate the boundary conditions that boost or hinder the influence of trait mindfulness as well as the success of mindfulness interventions for leaders’ authentic leadership. As noted by Good et al. (2016), “research on workplace mindfulness typically lacks adequate measurement of common individual differences (e.g., intelligence, attitudes, personality) … nor do studies typically control for organizational context (e.g., role, task characteristics, team climate), which may moderate the relation between the quality and practice of mindfulness and workplace outcomes.” (p. 21). For example, there is some (still inconclusive) evidence that individuals with low resource levels may benefit more from interventions due to having more room for improvement (e.g., Khoo, 2001). Thus, future studies may test the potential moderating influence of factors that have already been linked to mindfulness or authentic leadership (e.g., emotional stability, conscientiousness, psychological capital, leader self-knowledge and self-consistency; Giluk, 2009; Jensen & Luthans, 2006; Peus et al., 2012). With such information in hand, organizations would be better equipped to tailor mindfulness interventions to different groups of participants.

Practical Implications

The findings of our studies may provide organizations with important insights for both personnel selection and personnel development. Both studies underscore the benefits of selecting leaders who already have high levels of trait mindfulness, as those leaders will be more likely to exert authentic leadership. In addition, the results of study 2 indicate that mindfulness training may represent a valuable tool for improving leaders’ authentic leadership behaviors, which have, in turn, been shown to enhance their followers’ well-being and performance (Banks et al., 2016; Hoch et al., 2018). Notably, training mindfulness has been compared to training a muscle; thus, sustainable changes in mindfulness may require regular and long-term meditation practice. For this reason, we suggest that leaders treat a 4-week, app-based mindfulness training, such as the one used in the present study, as a starting point for integrating mindfulness meditation into their daily routines.

Mindfulness could be integrated as a substantial building block of leadership development programs, or might even be included in trainee programs in order to build leader mindfulness and authentic leadership in a sustainable way. In addition to offering adequate training, organizations should not neglect their responsibility to craft a working environment—e.g., via job design and organizational practices—that allows for and facilitates mindfulness and authentic leadership among their employees (Good et al., 2016; Hülsheger, 2015).

A Final Note

Despite the evidence that trait mindfulness and mindfulness interventions are associated with a variety of beneficial outcomes for individuals and organizations (Eby et al., 2017; Good et al., 2016; Lomas et al., 2017), there is a growing swell of criticism surrounding current mindfulness research and practices (e.g., Foster, 2016; Hülsheger, 2015; Purser & Loy, 2013; Van Dam et al., 2018). Several authors have criticized the shallow and popularized version of mindfulness (McMindfulness; Purser & Loy, 2013) for lacking the inherently genuine and ethical foundations that defined the original traditions. Two points are important to note in that regard: First, it has been discussed whether mindfulness meditation will always lead to more acceptance and kindness, uncovering people’s natural well of goodness, or if it may also be misused for doing harm with greater attentiveness and precision (see e.g., Purser & Loy, 2013). In traditional Buddhist teachings, mindfulness practice is inextricably intertwined with ethics, promoting benevolent and prohibiting harmful behavior (Baer & Nagy, 2017; Monteiro, Musten, & Compson, 2015). However, with the secularization of mindfulness-based interventions, mindfulness practice has been increasingly decontextualized from its Buddhist roots. This may potentially lead to what has been referred to as “wrong mindfulness” (cf. Monteiro et al., 2015) which can be associated with destructive and immoral behavior for individuals who lack a natural moral compass and empathy. In clinical contexts, researchers have therefore considered explicitly (re-)integrating ethics into mindfulness-based programs (Monteiro, Compson, & Musten, 2017), an initiative that is also worth considering in the context of mindfulness-based leadership training.

Second, despite our focus on a short-term and low-dose mindfulness intervention, we would like to emphasize that mindfulness trainings should never be regarded as a ‘quick fix’ for structural and deep-rooted problems in organizations (Kabat-Zinn, 2011). Organizations should follow a self-critical, holistic approach to cultivating mindfulness that addresses existing sources of stress rather than merely advertises wellness. It is only then that organizations can truly reap the benefits of authentic leadership.

References

Allen, T. D., Eby, L. T., Conley, K. M., Williamson, R. L., Mancini, V. S., & Mitchell, M. E. (2015). What do we really know about the effects of mindfulness-based training in the workplace? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8(4), 652–661. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.95.

Alvesson, M., & Einola, K. (2019). Warning for excessive positivity: Authentic leadership and other traps in leadership studies. The Leadership Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.04.001.

Amaro, A. (2015). A holistic mindfulness. Mindfulness, 6(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0382-3.

Antonakis, J., Fenley, M., & Liechti, S. U. E. (2011). Can charisma be taught? Tests of two interventions. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(3), 374–396.

Atwater, L. E., & Yammarino, F. J. (1992). Does self-other agreement on leadership perceptions moderate the validity of leadership and performance predictions? Personnel Psychology, 45(1), 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1992.tb00848.x.

Avolio, B. J., & Reichard, R. J. (2008). The rise of authentic followership. In The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations (pp. 325–337).San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass.

Avolio, B. J., Reichard, R. J., Hannah, S. T., Walumbwa, F. O., & Chan, A. (2009). A meta-analytic review of leadership impact research: Experimental and quasi-experimental studies. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(5), 764–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.06.006.