Abstract

Concerns about the gap between service quality in mental health systems and the growing literature on scientifically tested treatment approaches has led to multiple policy and practice initiatives calling for greater use of empirically supported interventions (ESIs) in children’s mental health systems. Despite the demonstrated efficacy of these approaches, some concerns remain about the current suitability of ESIs as a single strategy for improving service system quality. Issues raised include (a) the appropriateness of some interventions for individualized care or adaptation in response to emergent events, and (b) the ability for ESIs collectively to yield a comprehensive service array for youth and families. The current paper thus outlines one strategy to complement and extend that work, through a system for organizing and coordinating currently available ESIs as well as for building and adjusting individualized, evidence-informed plans when needed, using dedicated tools to inform treatment design, adaptation, and evaluation in real time. A case example is presented, and implications for treatment and research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental health concerns represent the most costly health problem of childhood, accounting for $8.9 billion of direct health care expenditures, with a cost-per-child more than double that of any of the next four most costly health conditions (i.e., asthma, trauma, bronchitis, infectious disease; Soni 2009). Despite these expenditures, only a portion of the services that do get delivered are appropriate and effective (Blau et al. 2010; Tolan and Dodge 2005; Weisz et al. 2006). The great disconnect between the needs of youth and families and the quality of services provided has understandably led to dozens of policy initiatives aimed at improving service quality through the application of empirically supported interventions (ESIs; cf. Silverman and Hinshaw 2008). Despite these historic changes in policy, the majority of youth and families in community mental health systems do not have access to ESIs; in fact, 75–80 % of young people who need behavioral health services do not even receive any services at all (Kataoka et al. 2002). A fundamental question facing the field involves how to increase both the quality and the availability of mental health services for children and families.

The Application of ESI to Community Care

The idea that service quality could be improved through the application of treatments tested and proven in research studies is quite logical at face value—so much that it seems remarkable that ESIs have not been subject to more widespread use in service systems. However, several issues have come to light over the past 10 years that may explain some of these challenges with implementation of high quality approaches.

Provider Preferences and Attitudes

An accumulation of findings has shown that ESIs are not highly favored among service providers. For example, Addis and colleagues (Addis and Krasnow 2000; Addis et al. 1999) surveyed providers’ attitudes toward ESIs and found that therapists were particularly concerned about the impact of standardized manuals on therapeutic rapport and individualized case conceptualization, with a general perception that ESIs might limit opportunities to exercise clinical judgment and thus to fully address the complexity of cases seen in community settings. (Nelson and Steele 2007). In a more recent comparative test, Borntrager et al. (2009) found that provider attitudes improved significantly for those trained in a flexible ESI relative to those trained in standard, less flexible ESIs, corroborating the notion that providers perceive a need for ESIs to be more flexible to accommodate the clinical complexity typical of community care.

The Relevance of ESIs

The widespread application of ESIs in a service population depends on the premise that one can assemble a comprehensive service array based on ESIs. In other words, in the ideal system, all youth and families would have one or more evidence-based options. However, recent investigation suggests that at present, such an arrangement of services is improbable, depending on the service system. Chorpita et al. (2011a) tested this question with youths from the Hawaii state mental health system by performing a structured comparison of youth characteristics to the characteristics of study participants in 437 randomized clinical trials. The results showed which ESIs could be applied to which youth in the service system, and two possible sets of nine ESIs emerged as potentially covering the largest percentage of the service population. However, each set only applied to a maximum of 71 % of the youths in the system when matching youth to treatments based on their primary problem, age, and gender. In other words, no array of ESIs could be assembled that served more than three-fourths of the service system population. When stricter matching criteria were enforced (requiring ESIs to match not only on problem, age, and gender, but also on ethnicity and setting), only 14 % of the youth in the Hawaii system were coverable. These results do not reflect negatively on the application of ESIs to community systems, but they do reflect negatively on the idea of ESIs as an exclusive strategy for improving service system quality, given that some youth and families will be without high quality options, due to the current state of the evidence base. When one considers workforce turnover, provider capacity (how many ESIs can one manage), geographic barriers (e.g., ability to implement full arrays in remote or rural communities), and families who don’t respond to their first treatment option (and thus need a second ESI), the need to consider multiple service quality strategies becomes obvious.

Selecting ESIs or Building Them from Parts

In an effort to address both of the concerns raised above—i.e., the perceived need for greater individualization of care and the ability to provide evidence-informed treatment to all youths and families within a system—Chorpita and Daleiden (in press) described a system for coordinating and selecting available ESIs and for providing individualized service to youths who are either not covered by or do not benefit from the ESIs in a given service array. Called Managing and Adapting Practice (MAP), this system involves a set of resources and models that organize individuals to provide and evaluate care using the best available evidence. This system is based on concepts that were a part of system design and performance improvement initiatives beginning over 10 years ago in the Hawaii system of care (e.g., Chorpita et al. 2002; Daleiden and Chorpita 2005; Daleiden et al. 2006), and the MAP concepts were more recently configured into a modular, flexible treatment that outperformed usual care and other ESIs in the Child STEPs randomized trial (Chorpita et al. 2005; Chorpita and Weisz 2009; Weisz et al. 2012). For a thorough description of the theory and rationale underlying MAP and its core concepts, the reader is referred to Chorpita and Daleiden (in press).

Managing and Adapting Practice’s direct service component is more like a treatment selection, design, implementation, and evaluation kit than a treatment itself. It is organized by a set of core concepts and decision models and uses specialized knowledge resources to inform key decisions in service delivery. For example, it employs a structured, searchable, and continually updated database of hundreds of randomized clinical trials (PracticeWise Evidence Based Services Database; PWEBS) to help develop an initial treatment plan and support ongoing decision-making. Treatments and their corresponding studies are identified according to well-defined guidelines (see Chorpita et al. 2011b, for a detailed description of the review process), which require among other things that studies used randomized controlled designs, involve a targeted population (i.e., are not universal prevention studies), and have a majority of study participants ages 18 or below. Accordingly, practice recommendations apply to clinical care for youth (whether directly or via their caregivers) rather than to clinical care explicitly for adults.

In its most common use, the PWEBS application returns a summary of all treatments meeting a user-defined strength of evidence that match a given youth’s characteristics. In other words, if a treatment team wishes to know what treatments meeting a commonly used definition of “evidence based” are suitable for a 9-year-old girl with disruptive behavior, PWEBS returns lists of all matching trials, all matching treatments, an aggregate summary showing the relative proportions of treatment types (e.g., parent management training, problem solving training), settings (e.g., clinic, school), and formats (e.g., individual, group). Thus, MAP’s direct service component guides the user to select an existing ESI if it is available in the system.

When such resources are not available or if a standard ESI has already been tried but the youth has not met established treatment goals, the MAP user can then design a treatment in real time, beginning with a list of procedures that are common to all of the matching evidence-based treatments (in this example of the 9-year-old girl, 30 evidence-based protocols tested in 26 randomized trials). Practices distilled from the aggregate literature (“common elements;” Chorpita et al. 2007) are listed and sorted according to the relative proportion of specific elements common across all of those protocols (e.g., 64 % of all evidence ESIs matching this 9-year-old girl used a rewards procedure).

Common elements refer specifically to discrete procedures that are components of ESIs (see Table 1 for examples). These elements are found by (a) identifying all candidate treatments meeting a given definition or standard of quality (i.e., defining “what is an ESI”), (b) identifying the practices that are part of those interventions, and (c) determining their relative frequency within those interventions. When planning for a specific case, the initial list of candidate ESIs is typically only those relevant to a set of youth or context characteristics (e.g., “ESIs for depressed mood in adolescent boys seen in an inpatient setting,” or “ESIs for 5 years old girls with ADHD,” etc.). Thus, the resulting list of common elements represents the procedures used most frequently as part of successful interventions for a given purpose. Providers can organize those elements into a plan according to common coordination rules emanating from the treatment outcome knowledge base, and specific therapeutic activity is then supported by a Practitioner Guide, a “how to” knowledge resource that spells out the important steps of each practice element in both a checklist and a detailed narrative format.

Another central aspect of the MAP system is a unifying evaluation framework to track outcomes and practices. Assessment involves progress monitoring of client status as well as the history of therapeutic practices used. MAP does not require a specific measurement model, but emphasizes the importance of relevant and rigorous measurement of progress and practice in clinical reasoning and coordinated care, with measures and the timing of their administration dictated by the nature of the decisions being made. For example, if decisions will be made about adaptations to treatment, outcome measures must be gathered frequently enough to precede those decision points. Whether the care provider has selected a standard ESI to be delivered within the larger MAP context or has designed an evidence-informed plan using common elements from the relevant literature, the service episode is always subject to real-time evaluation and, for those treatments that allow adaptation, to self-correction.

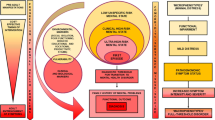

To facilitate this strategy, MAP uses clinical dashboards as a resource to organize and deliver messages from multiple evidence sources and multiple parties into a collaborative workspace (cf. Chorpita et al. 2008). Clinical dashboards present case context, progress, and practice history on a single display (see Fig. 1), and in typical MAP applications dashboard are created using a simple Excel™ spreadsheet platform that summarizes up to five user-selected progress measures (e.g., days in school, T-scores from a standardized assessment instrument) as well as the use of specific practice elements over time. Other information that can be represented on dashboards includes treatment team practice plans or progress benchmarks for celebration or additional review, research benchmarks of clinical cutoff scores, expected rates of change (e.g., Weersing 2005), expected best practice events such as session sequences from a treatment manual or practice elements retrieved from a PWEBS search, and administrative indicators for change in eligibility status, time or volume-based utilization triggers for re-authorization or intensive review, etc. Essentially, dashboards are telecommunication tools that support not only feedback, but also exploration and simulation (e.g., considering various “what if’s”). As such, dashboards can be useful not only to providers, but also to supervisors, youth, family members, and other members of a treatment team.

In this collaborative treatment design context, MAP’s direct service model also provides a variety of coordination resources, called “process guides,” which detail the logic of decision making and planning regarding selected aspects of care. For example, a Treatment Planner guide prompts the provider to coordinate the episode of care through selecting a therapeutic focus, organizing practices from the literature into logical early, middle, and late phases of care (referred to as “connect,” “cultivate,” and “consolidate” phases, respectively), and building a list of optional procedures to have on hand for likely sources of clinical interference (e.g., a rewards procedure to address low motivation). A Session Planner guide formalizes the planning and decision making regarding the structure of each session or clinical encounter, and outlines important steps to consider before and after each encounter (e.g., preparation, documentation). Another guide, called “The MAP,” offers an overarching model for clinical reasoning and service review throughout the entire service episode. An Embracing Diversity guide encourages the provider to engage in a structured consideration of possible adaptations to the plan, if indicated, across six different conceptual categories (prompting possible changes to conceptualization, communication, message, style, change agent, or therapeutic procedures).

Effective use of these multiple guides (e.g., coordinating both process and practice guides in an episode of clinical care) is typically achieved through a rigorous training and credentialing process outlined in the MAP professional development model. Training for direct service providers involves 52 h of instruction delivered over 6 months, including supervised clinical activity on at least two cases and the submission of a completed training portfolio for final review. Southam-Gerow et al. (in press) recently reported on an evaluation of training activities involving more than 1,700 direct service providers in Los Angeles County over a 33-months period. The authors reported an average time to completion for providers participating in a standard workshop and consultation sequence of 342 days and a pass rate for first portfolio submission of 86 % (see Southam-Gerow et al. in press, for a detailed description of the training model). Thus, there is evidence that this model can be trained rapidly and successfully on a relatively large scale.

In terms of youth outcomes, evidence is similarly promising in several contexts. For example, Daleiden et al. (2006) reported in an open trial in the Hawaii statewide system of care that average effect sizes for rate of change on standardized measures of youth functioning more than doubled over a 3-years period. In the Los Angeles County initiative, Southam-Gerow et al. (in press), reported an effects size of .76 (Cohen’s d) on a caregiver report measure of emotional and behavioral problems administered pre and post MAP for 1,172 youth. Finally, in the only randomized controlled trial testing a specific configuration of MAP for anxiety, depression, and conduct problems in youth ages 7–13, it outperformed not only a usual care control group but also a standard ESI group as well (Weisz et al. 2012).

More importantly, MAP exemplifies a missing piece of service system architecture: scientifically informed, personalized treatment options for youths who would otherwise not be served by any ESIs, because they are unavailable or do not match a youth’s particular characteristics, strengths, and needs.

Case Illustration

Calinda Fortune, LCSW is a child and adolescent clinical social worker at a community based center. Ms. Fortune began working with Gina B, an 11-year-old girl of African American ethnicity, to address concerns identified in a comprehensive behavioral health assessment following a referral by her pediatrician. Gina initially disclosed somatic symptoms (difficulty breathing, racing heart, shaking), which were especially pronounced at social events, gymnastics class, and in school. Gina’s parents also stated that they have noticed Gina “shying away from her friends and not wanting to leave the family home to go to school, even when they threaten punishment.” Ms. Fortune’s assessment included standardized measures based on self reports from Gina and her parents (Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scales; RCADS; Chorpita et al. 2000), a teacher interview, and her own clinical observation of the family relationships and Gina’s overall functioning. The assessment results indicated that social anxiety and shyness were primary concerns and thus, these were selected as the focus of treatment. Standardized assessment measures corroborated this formulation, with RCADS Social Anxiety T scores of 77 from Gina and 84 from her caregiver (both in the 99th percentile). In addition, Gina showed an elevated RCADS Depression T score of 68 (96th percentile) based on her self-report.

A PWEBS search based on Gina’s age and anxiety problems revealed that 57 ESIs tested in 43 randomized clinical trials matched her age and problem focus [including such programs as FRIENDS (Shortt et al. 2001), Coping Cat (Kendall and Hedtke 2006), MATCH-ADTC (Chorpita and Weisz 2009)]. With these indicated protocols unavailable in her service organization, Ms. Fortune proceeded to inspect the practice elements common to the 57 relevant ESIs listed. The most common practices included: exposure, cognitive therapy, psychoeducation, and relaxation (see Table 1). Using the Treatment Planner, a structured guide for ordering these and other relevant practices, Ms. Fortune worked collaboratively with the family to develop a working treatment plan. The initial phase of the plan—the “connect” phase—included exercises to increase therapeutic alliance and treatment engagement (youth engagement), to perform more detailed assessment of specific social fears (self-monitoring), and to orient Gina and her caregivers to the expectations, roles, and logic of the planned procedures (psychoeducation). The “cultivate” phase was tentatively organized to emphasize exercises to help Gina build coping skills as she approached socially anxiety provoking situations (exposure). Cognitive therapy and relaxation procedures were also noted as relevant and potentially useful should the need arise.

By the end of the fourth session, Ms. Fortune and Gina had accomplished practices to promote engagement and alliance and had covered psychoeducation for anxiety, which involved Socratic discussion about the features of anxiety and how the emotion can be managed and overcome through structured exercises and skill-building. The fourth session involved the development of a self-monitoring procedure involving a list of ten feared social situations for Gina, which were ordered in terms of increasing self-reported severity ratings. These situations included raising her hand in class, talking casually to other children at school, and volunteering to perform in front of others in her gymnastics group. Gina and her caregivers were asked to rate the severity of each of the ten feared items (using a 0–10 scale) once at home during the week to gather additional “clues” about the stability of these concerns over time.

Throughout the session, Gina revealed feeling hopeless about making any progress on any of the items listed, making frequent negative statements, such as “this might work for other kids, but I’m not like other kids,” “even if I can practice these things, I am just going to be more scared,” or “when this doesn’t work, it will be my fault.” Ms. Fortune explored these thoughts further, and discovered that Gina, who at times became tearful, held strong negative beliefs about herself and her future and had convinced herself that nothing could help, which she confessed reduced her motivation to continue treatment. Ms. Fortune was careful to validate and normalize Gina’s concerns, noting that it is common for some girls to “feel defeated before they begin,” which can be quite discouraging and painful. Ms. Fortune therefore assured Gina that she would plan on dealing more directly with these thoughts and feelings in the next session.

For sessions five and six, the original treatment plan was therefore adapted based both on this feedback from Gina and on evidence of depressed mood obtained at the initial assessment. A PWEBS search for depression in 11-year-olds showed six ESIs tested in five randomized clinical trials, and four of the six treatments were cognitive behavior therapy protocols. Given the limited number of results, Ms. Fortune performed a second search for depression, without using Gina’s age as a matching criterion. This search returned 35 evidence-based protocols, tested in 25 randomized trials. Again, the majority of treatments were cognitive behavior therapy, and the most common practice element was a cognitive procedure for managing depressive thinking (present in 72 % of successful treatments). Given the rational fit of this procedure with Gina’s pronounced negative beliefs and the fact that the cognitive practice element was common among ESIs for both anxiety and depressed mood, Ms. Fortune engaged in 2 sessions in which she helped Gina to understand the relationship of thoughts and feelings, to identify types of thinking habits that are not helpful, and to rehearse counter-thoughts for common types of situations. Gina practiced identifying and labeling her negative thoughts (e.g., “I won’t be any good at this” as an example of “guessing the worst”) and generating more supportive thoughts instead (e.g., “I’ve gotten good at some of the other things I’ve practiced, so maybe this will be the same.”). By the end of the sixth session, Gina demonstrated increased optimism about attempting to practice feared items on her list, although it was clear this new perspective would need to involve continued and deliberate effort on her part to apply her new skills.

At the seventh session, Gina’s father told the receptionist that he wanted the family to meet together with Ms. Fortune first after which Gina could meet alone if needed. Upon entering Ms. Fortune’s office, Mr. B declared they completed their homework and also did some “research on their own about social anxiety” even before sitting down. Gina, however, was extremely withdrawn, shaking, and could not make eye contact. Mrs. B was clasping her hands and looking back and forth between her husband and Gina. Out of concern for Gina’s apparent distress and tension among family members, Ms. Fortune asked if she could meet with Gina alone momentarily, and subsequently discovered that Gina was extremely anxious that “she was going to have to do things that would be too hard for her” and was now concerned that her therapy plan would overwhelm her.

Although Gina’s response was not entirely surprising, it represented another obstacle to moving forward to the planned activities of rehearsing a feared situation: Ms. Fortune had planned for that session to perform a role-play of a brief, friendly conversation with another child at school. Ms. Fortune therefore considered procedures from the anxiety research literature that were consistent with Gina’s current presentation. Given that relaxation had been identified earlier as a candidate practice, and given its fit with the Gina’s current presentation, Ms. Fortune proceeded to deliver an imagery-based relaxation technique. The technique helped Gina to become centered in the therapy room, to recall the safety of the therapeutic relationship, to slow her breathing, and ultimately to feel ready to take the next steps of her plan. Ratings of Gina’s anxiety level were taken before and after the relaxation, and showed that she was able to feel calmer and less worried after only 10 min of the relaxation exercise. Ms. Fortune brought the caregivers back into the session, and repeated the relaxation script for the entire family, noting first how Gina had been concerned and how listening to imagery had for the moment addressed her concerns. By the end of the session, all members of the Gina’s family were calmer and more engaged. Ms. Fortune discussed that Gina and the family could create their own imagery relaxations scripts to use at home, but also provided several handouts of scripts if Gina was alone and needed a reminder of how she able to relax during the session.

At the next session, Gina met with Ms. Fortune for the first 35 min alone. Gina reported that her family practiced the relaxation technique every evening. Gina relayed that the first few times they did it she thought it was “hokey to sit around and breathe with my mom and dad,” but it “did help me to fall asleep at night” and “helped me to focus as I got ready for school.” Ms. Fortune praised Gina for being motivated to practice the technique at home even when she thought it was “hokey.” Ms. Fortune practiced relaxation once more with Gina in that session, before they prepared to practice one of the items on her list of feared situations.

After reviewing the list together, Gina and Ms. Fortune agreed to practice asking a question in her science class. They began by making a list of possible questions and writing them down. At one point, Gina stated “that’s not how it works,” to indicate that the idea of reading cards with her therapist was “fake” and that she didn’t see how it could help. With a little prompting from Ms. Fortune, Gina quickly identified these thoughts as some of the habitual, critical thoughts for which she now had tools and skills. With encouragement, she was able to generate some new thoughts such as, “maybe I am just saying that because I’m nervous,” and “the relaxation felt hokey, too, but then it turned out to be helpful, so maybe this will, too.” For the remainder of that session, Gina and Ms. Fortune took turns asking each other the questions on the cards, each time taking ratings of anxiety to see whether the task became easier. By the end of the session, Gina was able to role play being in class and raising her hand. She demonstrated the role play to her parents, who were pleased, and the family agreed that Gina would try raising her hand at school twice during the week.

Together they continued to document Gina’s progress, and Gina was able to spend the next four sessions practicing items together in session and then at school, gymnastics class, or home during the week. Most tasks became easier after a few tries, and for those that were more difficult, Gina was able to prepare by practicing her relaxation skills before school and using her cognitive skills to address negative thinking when she felt discouraged.

A review of the dashboard at session 10 showed that her depression levels were reduced as measured in a 1-month assessment using the RCADS. Although her RCADS anxiety scores were still elevated at that time, they had decreased from her initial assessment, and more importantly, after the exposure practices began, her weekly ratings of feared items decreased dramatically in severity. Gina and her parents enjoyed seeing their “results” and were able to see that the recent practices and role plays were particularly useful at reducing her anxiety. It was agreed that Gina would continue to practice items on her list and to begin to select and rehearse these practices with less input from Ms. Fortune. By session 12, a second assessment using the RCADS showed improvements in all areas and a continued decrease in the weekly ratings of anxiety. Ms. Fortune performed a “maintenance” session that involved some exposure practice but also incorporated planning for the future, for termination, and for continued application of her skills in the face of future challenges. A final session was planned for a month in the future, so as to give Gina and her family time to practice on their own. In the final session, she reported continued practice of feared items and all of her scores indicated that her anxiety and depressed mood were no longer significant problems. Gina admitted to having difficult days now and then, but added that “now I know what to do when something is hard for me.”

Summary and Implications

Gina’s case represents application of the MAP direct service model in that it leveraged the knowledge resources (PWEBS, Practice Guides, and Process Guides) to build and adapt an evidence-informed treatment approach for a youth and family. Notable is the fact that Gina’s case required “exception handling” at the system level (i.e., no indicated ESI was available in Ms. Fortune’s workplace), at the treatment episode level (i.e., the original plan was adapted to include optional cognitive elements to address anticipated negative thinking), and at the clinical encounter level (i.e., the structured and empirically supported practice of relaxation was spontaneously introduced based on an unexpected display of distress from Gina within session 7). From the practice perspective, this case thus highlights the potential value of treatment approaches that offer structured pathways for the provider and the family in the face of exceptional individual characteristics or unanticipated circumstances. As Chorpita and Daleiden (in press) argued, when such structured options are not available, providers may be in a position either to ignore these exceptions (e.g., to push ahead even when Gina was too distressed to do so) or to improvise in an unstructured or unsupported manner (e.g., to engage in topical discussion, therapeutic play or some other activity for which there is less research support for its ability to help with social anxiety). Clinically, MAP offers a service architecture to identify these exceptions quickly (e.g., through PWEBS and the Clinical Dashboard) and to identify promising structured alternatives (e.g., through PWEBS and the Practice Guides), thus capitalizing on both the strength of the research while also allowing for locally informed adjustments based on current evidence and observations from the youth and family.

Decades of research have brought us both products (ESIs) and knowledge about what works for whom. The MAP system provides architecture and infrastructure to “feed-forward” all of that information in support of clinical decision-making with youth and families to make informed, empirically grounded “best guesses” about what might work in their specific situation, and to “feed-back” information about whether the activities to date are yielding desired results. Program evaluation has suggested that when implemented as a direct service model, MAP may yield favorable results (Southam-Gerow et al. in press) and a randomized trial has found that assembly of a specific treatment using the MAP architecture (Weisz et al. 2012) performs well relative to usual care and standard manualized treatment in community settings.

However, the relative contribution of various aspects of MAP (structured practice, guided decision-making, visualization and feedback via dashboard, introduction of a common language, etc.) remain to be determined. Also, MAP provides guidance regarding relevant sources of evidence and common practices, but specific algorithms have not been tested at each decision-making point. For example, how much evidence for lack of progress should be obtained before a decision is made to “adapt” from an empirically supported protocol or what case features constitute an “exception?” What sources of evidence in addition to targeted problem and client preferences would improve decision-making about best practices to attempt first? How much supervision or quality review is helpful to both support providers’ professional development and provide case-specific guidance to improve client outcomes? Given limited resources for monitoring and quality assurance, how much emphasis should be placed on episode management relative to encounter (i.e., clinical event) management or engagement management relative to practice management or outcome management?

Until such questions can be addressed by controlled research, MAP contends with these questions by providing a framework for their coordination and by identifying when and where such answers will be useful in the service delivery process. Without all of those answers yet in hand, we believe there is a place for continued research and development regarding service models that balance a collaborative and strategic use of evidence with the need to individualize or adapt to common exceptions that may arise within systems, within treatment episodes, and within clinical encounters.

References

Addis, M. E., & Krasnow, A. (2000). A national survey of practicing psychologists’ attitudes toward psychotherapy treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 331–339.

Addis, M. E., Wade, W. A., & Hatgis, C. (1999). Barriers to evidence-based practices: Addressing practitioners’ concerns about manual-based psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 430–441.

Blau, G. M., Huang, L. N., & Mallery, C. J. (2010). Advancing efforts to improve children’s mental health in America: A commentary. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37, 140–144.

Borntrager, C. F., Chorpita, B. F., Higa-McMillan, C., & Weisz, J. R. (2009). Provider attitudes toward evidence-based practices: Are the concerns with the evidence or with the manuals? Psychiatric Services, 60, 677–681.

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11, 141–156.

Chorpita, B. F., Becker, K. D., & Daleiden, E. L. (2007). Understanding the common elements of evidence based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 647–652.

Chorpita, B. F., Bernstein, A. D., Daleiden, E. L., & The Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2008). Driving with roadmaps and dashboards: Using information resources to structure the decision models in service organizations. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35, 114–123.

Chorpita, B. F., Bernstein, A., & Daleiden, E. L. (2011a). Empirically guided coordination of multiple evidence-based treatments: An illustration of relevance mapping in children’s mental health services. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 470–480.

Chorpita, B. F., & Daleiden, E. L. (in press). Structuring the collaboration of science and service in pursuit of a shared vision. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology.

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., Ebesutani, C., Young, J., Becker, K. D., Nakamura, B. J., et al. (2011b). Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18, 153–171.

Chorpita, B. F., & Weisz, J. R. (2009). MATCH-ADTC: Modular approach to therapy for children with anxiety, depression, trauma, or conduct problems. Satellite Beach, FL: PracticeWise.

Chorpita, B. F., Yim, L. M., Donkervoet, J. C., Arensdorf, A., Amundsen, M. J., McGee, C., et al. (2002). Toward large-scale implementation of empirically supported treatments for children: A review and observations by the Hawaii Empirical Basis to Services Task Force. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9, 165–190.

Chorpita, B. F., Yim, L. M., Moffitt, C. E., Umemoto, L. A., & Francis, S. E. (2000). Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: A revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 835–855.

Daleiden, E., & Chorpita, B. F. (2005). From data to wisdom: Quality improvement strategies supporting large-scale implementation of evidence based services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14, 329–349.

Daleiden, E. L., Chorpita, B. F., Donkervoet, C. M., Arensdorf, A. A., & Brogan, M. (2006). Getting better at getting them better: Health outcomes and evidence-based practice within a system of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 749–756.

Kataoka, S., Zhang, L., & Wells, K. (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 1548–1555.

Kendall, P. C., & Hedtke, K. A. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: Therapist manual (3rd ed.). Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing.

Nelson, T. D., & Steele, R. G. (2007). Predictors of practitioner self-reported use of evidence-based practices: Practitioner training, clinical setting, and attitudes toward research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 34, 319–330.

Shortt, A., Barrett, P., & Fox, T. (2001). Evaluating the FRIENDS program: A cognitive-behavioral group treatment for anxious children and their parents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 525–535.

Silverman, W. K., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents: A ten year update [Special Issue]. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 1–301.

Soni, A. (2009). The five most costly children’s conditions, 2006: Estimates for the U.S. Civilians Noninstitutionalized Children, Aged 0–17. Statistical Brief #242. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Southam-Gerow, M. A., Daleiden, E. L., Chorpita, B. F., Bae, C. Mitchell, C., Faye, M., & Alba, M. (in press). MAPping Los Angeles County: Taking an evidence-informed model of mental health care to scale. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology.

Tolan, P. H., & Dodge, K. A. (2005). Children’s mental health as a primary care and concern: A system for comprehensive support and service. American Psychologist, 60, 601–614.

Weersing, V. R. (2005). Benchmarking the effectiveness of psychotherapy: Program evaluation as a component of evidence-based practice. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 1058–1062.

Weisz, J. R., Chorpita, B. F., Palinkas, L. A., Schoenwald, S. K., Miranda, J., Bearman, S. K., et al. (2012). Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy with youth depression, anxiety, and conduct problems: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 274–282.

Weisz, J. R., Jensen-Doss, A., & Hawley, K. M. (2006). Evidence-based youth psychotherapies versus clinical care: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. American Psychologist, 61, 671–689.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chorpita, B.F., Daleiden, E.L. & Collins, K.S. Managing and Adapting Practice: A System for Applying Evidence in Clinical Care with Youth and Families. Clin Soc Work J 42, 134–142 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-013-0460-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-013-0460-3