Abstract

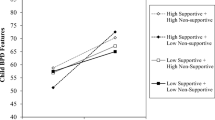

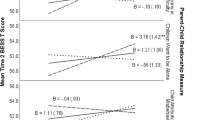

The transaction of adolescent’s expressed negative affect and parental interpersonal emotion regulation are theoretically implicated in the development of borderline personality disorder (BPD). Although problem solving and support/validation are interpersonal strategies that foster emotion regulation, little is known about whether these strategies are associated with less BPD severity among adolescents. Adolescent girls (age 16; N = 74) and their mothers completed a conflict discussion task, and maternal problem solving, support/validation, and girls’ negative affect were coded. Girls’ BPD symptoms were assessed at four time points. A 3-way interaction of girls’ negative affect, problem solving, and support/validation indicated that girls’ negative affect was only associated with BPD severity in the context of low maternal support/validation and high maternal problem solving. These variables did not predict changes in BPD symptoms over time. Although high negative affect is a risk for BPD severity in adolescent girls, maternal interpersonal emotion regulation strategies moderate this link. Whereas maternal problem solving coupled with low support/validation is associated with a stronger negative affect-BPD relation, maternal problem solving paired with high support/validation is associated with an attenuated relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Of note, when maternal problem solving was considered as the independent variable, and girls’ negative affect and maternal support/validation were considered as moderators, maternal problem solving was associated with lower BPD severity in the context of low girls’ negative affect and low maternal support/validation, B = −0.28, SE = 0.12, z = −2.38, p = .02. In contrast, in the context of low girls’ negative affect and high maternal support/validation, there was no significant association between maternal problem solving and BPD severity, B = 0.21, SE = .27, z = 0.77, p = .44. In the context of high girls’ negative affect and low maternal support/validation, problem solving was marginally associated with BPD severity, B = 0.50, SE = 0.27, z = 1.87, p = .06, whereas in the context of high girls’ negative affect and high maternal support/validation, maternal problem solving was marginally associated with lower BPD severity, B = −0.38, SE = 0.21, z = −1.76, p = .08. In terms of regions of significance, simple slopes were significant outside the region demarcated by girls’ negative affect at the lower bound (−1.12) and upper bound (2.36) of low maternal support/validation.

Although the incorporation of repeated measures of BPD severity increases our power to detect significant effects (Raudenbush and Xiao-Feng 2001), given the absence of significant interactions with time, we trimmed the interactions with time from the model and estimated the model again. The interaction of girls’ negative affect, maternal problem solving, and maternal support/validation remained significant, B = −0.12, SE = 0.05, p = .02.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bateman, A. W., & Fonagy, P. (2004). Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(1), 36–51.

Beauchaine, T. P., Klein, D. N., Crowell, S. E., Derbidge, C., & Gatzke-Kopp, L. (2009). Multifinality in the development of personality disorders: A biology × Sex × environment interaction model of antisocial and borderline traits. Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 735–770. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000418.

Becker, D. F., McGlashan, T. H., & Grilo, C. M. (2006). Exploratory factor analysis of borderline personality disorder criteria in hospitalized adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47(2), 99–105. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.07.003.

Birmaher, B., Khetarpal, S., Brent, D., Cully, M., Balach, L., Kaufman, J., & Neer, S. M. (1997). The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 545–553. doi:10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018.

Carlson, E. A., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (2009). A prospective investigation of the development of borderline personality symptoms. Development and Psychopathology, 21(4), 1311–1334. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990174.

Chabrol, H., Montovany, A., Ducongé, E., Kallmeyer, A., Mullet, E., & Leichsenring, F. (2004). Factor structure of the borderline personality inventory in adolescents. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 20, 59–65.

Chanen, A. M., & McCutcheon, L. (2013). Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: Current status and recent evidence. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(s54), s24–s29. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119180.

Crowell, S. E., Beauchaine, T. P., & Linehan, M. M. (2009). A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 495–510. doi:10.1037/a0015616.

Crowell, S. E., Beauchaine, T. P., McCauley, E., Smith, C. J., Vasilev, C. A., & Stevens, A. L. (2008). Parent-child interactions, peripheral serotonin, and self-inflicted injury in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 15–21. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.15.

Davidov, M., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development, 77(1), 44–58. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x.

Feng, B. (2009). Testing an integrated model of advice giving in supportive interactions. Human Communication Research, 35(1), 115–129. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2008.01340.x.

Fruzzetti, A. E., Shenk, C. E., & Hoffman, P. D. (2005). Family interaction and the development of borderline personality disorder: A transactional model. Development and Psychopathology, 17(4), 1007–1030. doi:10.1017/S0954579405050479.

Furman, W., & Shomaker, L. B. (2008). Patterns of interaction in adolescent romantic relationships: Distinct features and links to other close relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 31(6), 771–788. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.10.007.

Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (1998). Adolescent symptom inventory-4 norms manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus.

Gadow, K. D., Sprafkin, J., Carlson, G. A., Schneider, J., Nolan, E. E., Mattison, R. E., & Rundberg-Rivera, V. (2002). A DSM-IV-referenced, adolescent self-report rating scale. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(6), 671–679. doi:10.1097/00004583-200206000-00006.

Gnepp, J., & Hess, D. L. (1986). Children’s understanding of verbal and facial display rules. Developmental Psychology, 22, 103–108.

Hale, W. W., Raaijmakers, Q., Muris, P., & Meeus, W. (2005). Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED) in the general adolescent population. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(3), 283–290. doi:10.1097/00004583-200503000-00013.

Hill, J., Stepp, S. D., Wan, M. W., Hope, H., Morse, J. Q., Steele, M., et al. (2011). Attachment, borderline personality, and romantic relationship dysfunction. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(6), 789–805. doi:10.1521/pedi.2011.25.6.789.

Hipwell, A. E., Loeber, R., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Keenan, K., White, H. R., Kroneman, L., et al. (2006). Characteristics of girls with early onset disruptive and antisocial behaviour. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 12(1), 99–118. doi:10.1002/cbm.489.

Hofmann, S. G. (2014). Interpersonal emotion regulation model of nood and anxiety disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(5), 483–492. doi:10.1007/s10608-014-9620-1.

Hughes, A. E., Crowell, S. E., Uyeji, L., & Coan, J. A. (2012). A developmental neuroscience of borderline pathology: Emotion dysregulation and social baseline theory. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(1), 21–33. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9555-x.

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Chen, H., Kasen, S., & Brook, J. S. (2006). Parenting behaviors associated with risk for offspring personality disorder during adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(5), 579–587. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.579.

Keenan, K., Hipwell, A., Chung, T., Stepp, S. D., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Loeber, R., & McTigue, K. (2010). The Pittsburgh girls study: Overview and initial findings. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39(4), 506–521. doi:10.1080/15374416.2010.486320.

Krause, E. D., Mendelson, T., & Lynch, T. R. (2003). Childhood emotional invalidation and adult psychological distress: The mediating role of emotional inhibition. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(2), 199–213. doi:10.10.16/16/S0145-2134(02)00536-7.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

McMakin, D. L., Burkhouse, K. L., Olino, T. M., Siegle, G. J., Dahl, R. E., & Silk, J. S. (2011). Affective functioning among early adolescents at high and low familial risk for depression and their mothers: A focus on individual and transactional processes across contexts. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(8), 1213–1225. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9540-4.

Morey, L. C. (1991). The personality assessment inventory professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development (Oxford, England), 16(2), 361–388. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x.

O’Connor, T. G., Hetherington, E. M., Reiss, D., Plomin, R., Connor, O., & O’Connor, T. G. (1995). A twin–sibling study of observed parent–adolescent interactions. Child Development, 66(3), 812–829.

Pfohl, B., Blum, N., & Zimmerman, M. (1997). Structured interview for DSM-IV personality: SIDP-IV. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(4), 437–448. doi:10.3102/10769986031004437.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Xiao-Feng, L. (2001). Effects of study duration, frequency of observation, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods, 6, 387–401. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.387.

Sauer, S. E., & Baer, R. A. (2010). Validation of measures of biosocial precursors to borderline personality disorder: Childhood emotional vulnerability and environmental invalidation. Assessment, 17(4), 454–466. doi:10.1177/1073191110373226.

Schuppert, H. M., Albers, C. J., Minderaa, R. B., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., & Nauta, M. H. (2014). Severity of borderline personality symptoms in adolescence: Relationship with maternal parenting stress, maternal psychopathology, and rearing styles. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28, 155–168. doi:10.1521/pedi_2104_28_155.

Scott, L. N., Stepp, S. D., Hallquist, M. N., Whalen, D. J., Wright, A. G. C., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2015). Daily shame and hostile irritability in adolescent girls with borderline personality disorder symptoms. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 6, 53–63. doi:10.1037/per000010710.1037/per00001.

Sheeber, L., Allen, N., Davis, B., & Sorensen, E. (2000). Regulation of negative affect during mother–child problem–solving interactions: Adolescent depressive status and family processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28(5), 467–479. doi:10.1023/A:1005135706799.

Shenk, C. E., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2011). The impact of validating and invalidating responses on emotional reactivity. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(2), 163–183. doi:10.1521/jscp.2011.30.2.163.

Shenk, C. E., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2014). Parental validating and invalidating responses and adolescent psychological functioning: An observational study. The Family Journal, 22(1), 43–48. doi:10.1177/1066480713490900.

Steinberg, L., Dahl, R., Keating, D., Kupfer, D. J., Masten, A. S., & Pine, D. S. (2006). The study of developmental psychopathology in adolescence: Integrating affective neuroscience with the study of context. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology, Vol 2: Developmental neuroscience (2nd ed., pp. 710–741). Hoboken: Wiley.

Stepp, S. D., Whalen, D. J., Pilkonis, P. A., Hipwell, A. E., & Levine, M. D. (2012). Children of mothers with borderline personality disorder: Identifying parenting behaviors as potential targets for intervention. Personality Disorders, 3(1), 76–91. doi:10.1037/a0023081.

Stepp, S. D., Whalen, D. J., Scott, L. N., Zalewski, M., Loeber, R., & Hipwell, A. E. (2014). Reciprocal effects of parenting and borderline personality disorder symptoms in adolescent girls. Development and Psychopathology, 26(2), 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0954579413001041.

Trull, T. J. (1995). Borderline personality disorder features in nonclinical young adults: 1. Identification and validation. Psychological Assessment, 7(1), 33–41. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.1.33.

Van Asselt, A. D. I., Dirksen, C. D., Arntz, A., & Severens, J. L. (2007). The cost of borderline personality disorder: Societal cost of illness in BPD-patients. European Psychiatry, 22, 354–361.

Whalen, D. J., Scott, L. N., Jakubowski, K. P., McMakin, D. L., Hipwell, A. E., Silk, J. S., & Stepp, S. D. (2014). Affective behavior during mother–daughter conflict and borderline personality disorder severity across adolescence. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 5(1), 88–96. doi:10.1037/per0000059.

Wright, A. C. G., Zalewski, M., Hallquist, M. N., Hipwell, A. E., & Stepp, S. D. (2015). Developmental trajectories of borderline personality disorder symptoms and psychosocial functioning in adolescence. Journal of Personality Disorders. doi:10.1521/pedi_2015_29_200.

Zaki, J., & Williams, W. C. (2013). Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion, 13(5), 803–810. doi:10.1037/a0033839.

Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Dubo, E. D., Sickel, A. E., Trikha, A., Levin, A., & Reynolds, V. (1998). Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 1733–1739. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.009.

Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Hennen, J., & Silk, K. R. (2003). The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 274–283. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274.

Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Vujanovic, A. A., Hennen, J., Reich, D. B., & Silk, K. R. (2004). Axis II comorbidity of borderline personality disorder: Description of 6-year course and prediction to time-to-remission. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110(6), 416–420. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00362.x.

Zanarini, M. C., Horwood, J., Wolke, D., Waylen, A., Fitzmaurice, G., & Grant, B. F. (2011). Prevalence of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder in two community samples: 6330 English 11-year-olds and 34,653 American adults. Journal of Personality Disorders, 25(5), 607–619. doi:10.1521/pedi.2011.25.5.607.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the families of the Pittsburgh Girls Study for their dedication and ongoing participation in this project. This research was supported by Grants from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (95-JD-FX-0018) and from the National Institute on Mental Health (MH56630). Diana J. Whalen’s effort was supported by T32 MH100019 to Drs. Deanna Barch and Joan Luby. Lori N. Scott’s effort was supported by K01 MH101289. Stephanie D. Stepp’s effort was supported by K01 MH086713.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Katherine L. Dixon-Gordon, Diana J. Whalen, Lori N. Scott, Nicole D. Cummins and Stephanie D. Stepp declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent.

Animal Rights

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dixon-Gordon, K.L., Whalen, D.J., Scott, L.N. et al. The Main and Interactive Effects of Maternal Interpersonal Emotion Regulation and Negative Affect on Adolescent Girls’ Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms. Cogn Ther Res 40, 381–393 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-015-9706-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-015-9706-4