Abstract

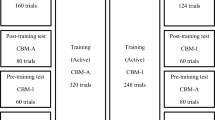

There is growing evidence that cognitive bias modification procedures targeting attention (CBM-A) can alter anxiety reactivity in the laboratory, and also can yield therapeutic benefits for clinically anxious patients. These promising findings underscore the need for investigators to delineate the conditions under which CBM-A procedures are effective. In the present research we conducted two studies to empirically determine whether CBM-A continues to be effective when participants are informed of the training contingency and instructed to actively practice the target pattern of attentional selectivity. These studies were designed to address two key questions relating to this issue. First, if participants are informed of the training contingency and instructed to practice the target pattern of attentional selectivity, then will the CBM-A manipulation still effectively modify attentional response to negative information? Second, if it does still modify attentional response to negative information under these conditions, then will this change in attentional selectivity still serve to alter anxiety responses to a stressful experience? The results indicate that when participants are informed of the training contingency and instructed to practice the target pattern of attentional selectivity, then the CBM-A manipulation continues to exert an impact on attentional selectivity, but this modification of attentional bias no longer affects anxiety reactivity to a subsequent stressor. We discuss both the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This represents a lenient criterion, as a participant randomly endorsing three options would have a 43 % probability of endorsing the valence option by chance alone.

Assuming the conventional levels of α = .05 and β = .80.

References

Amir, N., Beard, C., Burns, M., & Bomyea, J. (2009a). Attention modification program in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 28–33.

Amir, N., Beard, C., Taylor, C. T., Klumpp, H., Elias, J., et al. (2009b). Attention training in individuals with generalized social phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 961–973.

Amir, T., & Taylor, C. (2012). Combining computerized home-based treatments for generalized anxiety disorder: An attention modification program and cognitive behavioral therapy. Behavior Therapy, 43, 546–559.

Amir, N., Weber, G., Beard, C., Bomyea, J., & Taylor, C. (2008). The effect of a single-session attention modification program on response to a public-speaking challenge in socially anxious individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 860–868.

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 1–24.

Barnes, L. L., Harp, D., & Jung, W. S. (2002). Reliability generalization of scores on the Spielberger state-trait anxiety inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62, 603–618.

Beard, C. (2011). Cognitive bias modification for anxiety: Current evidence and future directions. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 11, 299–311.

Beard, C., Sawyer, A. T., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Efficacy of attention bias modification using threat and appetitive stimuli: A meta-analytic review. Behavior Therapy, 43, 724–740.

Beard, C., Weisberg, R. B., Perry, A., Schofield, C., & Amir., N. (2010) Feasability and acceptability of CBM in primary care settings. Presented at World Congress of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. Boston, MA, USA. 2–5 June 2010.

Berry, D. C., & Broadbent, D. E. (1984). On the relationship between task performance and associated verbalizable knowledge. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 36A, 209–231.

Browning, M., Holmes, E., Murphy, S., Goodwin, G., & Harmer, C. (2010). Lateral prefrontal cortex mediates the cognitive modification of attentional bias. Biological Psychiatry, 67, 919–925.

Carlbring, P., Apelstrand, M., Sehlin, H., Amir, N., Rousseau, A., Hofmann, S., et al. (2012). Internet-delivered attention bias modification training in individuals with social anxiety disorder—a double blind randomized control trial. BMC Psychiatry, 12(66).

Dandeneau, S. D., & Baldwin, M. W. (2004). The inhibition of socially rejecting information among people with high versus low self-esteem: the role of attentional bias and the effects of bias reduction training. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 584–602.

Eldar, S., Apter, A., Lotan, D., Edgar, K. P., Naim, R., Fox, N. A., et al. (2012). Attention bias modification treatment for pediatric anxiety disorders: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 213–220.

Eldar, S., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2010). Neural plasticity in response to attention training in anxiety. Psychological Medicine, 40, 667–677.

Eldar, S., Ricon, T., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2008). Plasticity in attention: implications for stress response in children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 450–461.

Farrow, D., & Abernethy, B. (2002). Can anticipatory skills be learned through implicit video-based perceptual training? Journal of Sports Sciences, 20, 471–485.

Foorman, B. R., Francis, D. J., Fletcher, J. M., Schatschneider, C., & Mehta, P. (1998). The role of instruction in learning to read: Preventing reading failure in at-risk children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 37–55.

Grafton, B., Ang, C., & MacLeod, C. (2012). Always look on the bright side of life: The attentional basis of positive affectivity. European Journal of Personality, 26, 133–144.

Green, T. D., & Flowers, J. H. (1991). Implicit versus explicit learning processes in a probabilistic, continuous fine-motor catching task. Journal of Motor Behaviour, 23(4), 293–300.

Haeffel, G., Rozek, D., Hames, J., & Technow, J. (2012). Too much of a good thing: Testing the efficacy of a cognitive bias modification task for cognitively vulnerable individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36, 493–501.

Hagan, R., & MacLeod, C. (1992). Individual differences in the selective processing of threatening information, and emotional responses to a stressful life event. Behavior Research and Therapy, 30, 151–161.

Hakamata, Y., Lissek, S., Bar-Haim, Y., Britton, J. C., Fox, N. A., et al. (2010). Attention bias modification treatment: A meta-analysis toward the establishment of novel treatment for anxiety. Biological Psychiatry, 68, 982–990.

Hazen, R. A., Vasey, M. W., & Schmidt, N. B. (2009). Attentional retraining: A randomized clinical trial for pathological worry. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43, 627–633.

Heeren, A., Lievens, L., & Philipot, P. (2011). How does attention training work in social phobia: Disengagement from threat or re-engagement to non-threat? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25, 1108–1115.

Heeren, A., Reese, H. E., McNally, R. J., & Philippot, P. (2012). Attention training toward and away from threat in social phobia: Effects on subjective, behavioral, and physiological measures of anxiety. Behavior Research and Therapy, 50, 30–39.

Julian, K., Beard, C., Schmidt, N., Powers, M., & Smits, J. (2012). Attention training to reduce attention bias and social stressor reactivity: An attempt to replicate and extend previous findings. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 350–358.

Kaltenthaler, E., Sutcliffe, P., Parry, G., Beverly, C., Rees, A., & Ferriter, M. (2008). The acceptability to patients of computerized cognitive behviour therapy for depression: A systematic review. Psycholoigcal Medicine, 38, 1521–1530.

Koster, E., Baert, S., Bockstaele, M., & De Raedt, R. (2010). Attentional retraining procedures: Manipulating early of late components of attentional bias. Emotion, 10, 230–236.

Krebs, G., Hirsch, C. R., & Mathews, A. (2010). The effect of attention modification with explicit versus minimal instructions on worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 251–256.

MacLeod, C., Koster, E., & Fox, E. (2009). Whither cognitive bias modification research? Commentary on the special section articles. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 89–99.

MacLeod, C., & Mathews, A. (2012). Cognitive bias modification approaches to anxiety. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 189–217.

MacLeod, C., Mathews, A., & Tata, P. (1986). Attentional bias in emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95, 15–20.

MacLeod, C., Rutherford, E., Campbell, L., Ebsworthy, G., & Holker, L. (2002). Selective attention and emotional vulnerability: Assessing the causal basis of their association through the experimental manipulation of attentional bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 107–123.

MacLeod, C., Soong, L., Rutherford, E., & Campbell, L. (2007). Internet-delivered assessment and manipulation of anxiety-linked attentional bias: Validation of free access attentional probe software package. Behavior Research and Methods, 39, 533–538.

Manikandan, S. (2010). Data transformation. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics, 1, 126–127.

Mathews, A., & MacLeod, C. (2005). Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 167–195.

Mullen, R., Hardy, L., & Oldham, A. (2007). Implicit and explicit control of motor actions: Revisiting some early evidence. British Journal of Psychology, 98, 141–156.

Najmi, S., & Amir, N. (2010). The effect of attention training on a behavioral test of contamination fear in individuals with subclinical obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119, 136–142.

Oei, T. P., Evans, L., & Crook, G. M. (1990). Utility and validity of the STAI with anxiety disorder patients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29, 429–432.

Osborne, J. (2002). Notes on the use of data transformations. Practical Assessment, Research and Evalutation, 8.

Rapee, R. M., MacLeod, C., Carpenter, L., Gaston, J., Frei, J., Peters, L., et al. (2013). Integrating cognitive bias modification into a standard cognitive behavioural treatment package for social phobia: A randomized control trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 207–215.

Sanders, A. F., & Lamers, J. M. (2002). The Eriksen flanker effect revisited. Acta Psychologica, 109, 41–56.

Schmidt, N. B., Richey, J., Buckner, J. D., & Timpano, K. R. (2009). Attention training for generalized social anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 5–14.

Smeeton, N. J., Williams, A. M., Hodges, N. J., & Ward, P. (2005). The relative effectiveness of various instructional approaches in developing anticipation skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 11, 98–110.

Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, R., Vagg, P., & Jacobs, G. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory STAI (Form Y): Self-evaluation questionnaire. Alto, Ca: Consulting Psychologist Press.

Teachman, B., Joormann, J., Steinman, S., & Gotlib, I. (2012). Automaticity in anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 575–603.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Australian Research Council Grant DP0879589, and by a grant from the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research, CNCS-UEFISCDI, Project Number PNII-ID-PCCE-2011-2-0045.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

CAQ: Part A

Please think back to the first stage of the experiment in which you had to indicate whether one dot or two dots appeared on the screen after the words.

What do you think predicted where (in the location of the top or bottom word) the probe would more often appear? Please make any comments that come to mind even if you think it is just a guess or intuition about some aspect of the way you did the task_________

CAQ: Part B

Please answer Questions 1 and 2 for each of the Word Characteristics.

If you answer YES in Column 1 to any of the characteristics, then answer question 3 for that characteristic.

Word Characteristic | 1. | 2. | 3. |

|---|---|---|---|

Do you think that this word characteristic predicted the probe location? (yes or no) | How confident are you that your chosen answer is correct (0–100 %) | Where do you think the probe more often appeared? (circle one of the two options for the characteristic listed below that you think the probe appeared more often in) | |

Example: the length of the words | Yes | 50 % |

|

The concreteness of the words | More concrete word More abstract word | ||

The number of syllables in the words | Word with more syllables Word with fewer syllables | ||

The emotional tone of the words | Negative word Neutral word | ||

How frequently the words get used in English language | More frequent word Less frequent word | ||

Text brightness of the words | Word that looked brighter Word that looked less bright | ||

Number of vowels in the words | Word with more vowels Word with fewer vowels | ||

Verb vs non-verb status of the word | Word that were verbs Word that were non-verbs |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grafton, B., Mackintosh, B., Vujic, T. et al. When Ignorance is Bliss: Explicit Instruction and the Efficacy of CBM-A for Anxiety. Cogn Ther Res 38, 172–188 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9579-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9579-3