Abstract

In this study, the researchers examined the relationship between residential treatment staff members’ use of cognitive and behavioral disputations and problem-solving skills just prior to discharge for 59 youths with emotional and behavioral disorders. The researchers also assessed the direct and indirect effects of engagement in treatment on problem-solving. Measures completed by youths, childcare staff, and clinicians were used in order to comprehensively understand these relationships. The relationship between cognitive and behavioral disputations, as measured by both youth and staff, and problem-solving skills was not significant. Youth and staff reports of engagement in treatment related directly to youth report, but not staff report, of cognitive and behavioral disputations. Youth report of engagement was the only predictor of problem-solving just prior to discharge. Implications for engaging youth in treatment are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The youths were given an expected duration of stay when admitted to the agencies. These were used to determine the expected midpoint of the youth’s stay.

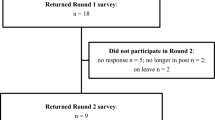

Missing data were imputed only if a single item was missing from a scale using the mean of the respondent’s other responses to the other questions in the scale. No more than 10 respondents were added as a result of this imputation. The majority of the missing data in this sample were due to items being entirely missing due to dropping out of the study or the refusal to answer certain sets of questions, cases in which imputation would be inappropriate. There were no significant differences between those included in the analysis and those excluded on length of stay, gender, or race/ethnicity. To determine if the data were missing systematically, a series of logistic regression models were estimated with “missing” as the dependent variable and a variety of intake characteristics (i.e., age at admission, gender, number of prior placements, self-reported types of general delinquency, self-reported arrest history, self-reported peer norms, abuse history, alcohol abuse, etc.), and the interactive terms among selected variables (i.e., delinquency and arrest history, delinquency and peer norms, etc.), as well as some non-linear transformation of them [i.e., age2, log(abuse history), etc.]. As there were no significant predictors of missingness, the data were considered to be missing at random.

Although we imputed missing data for those respondents missing single items in a scale, we could not salvage data from cases wherein the entire scale or more than one item in the scale was missing. As listwise deletion is used when performing path analysis, the sample size was reduced when any respondent was missing a response to any variable used in the analysis.

As the education staff only see the youths for a part of the youth’s day and in limited circumstances (only in class), it was thought that they would not be the best respondent for understanding youth’s overall engagement and the provision of cognitive and behavioral disputations.

These letter grades represent an approximate average to above average level of achievement for the youths.

References

Armelius, B. Å., & Andreassen, T. H. (2007). Cognitive–behavioral treatment for antisocial behavior in youth in residential treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4), Art. No.: CD005650. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005650.pub2.

Baker, A. J. L., Kurland, D., Curtis, P., Alexander, G., & Papa-Lentini, C. (2007). Mental health and behavioral problems of youth in the child welfare system: Residential treatment centers compared to therapeutic foster care in the Odyssey project population. Child Welfare, 86, 97–123.

Barth, R. P., Greeson, J. K. P., & Guo, S. (2007). Outcomes for youth receiving intensive in-home therapy or residential care: A comparison using propensity scores. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 497–505.

Beck, R., & Fernandez, E. (1998). Cognitive–behavioral therapy in the treatment of anger: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 63–74.

Bennett, D. S., & Gibbons, T. A. (2000). Efficacy of child cognitive–behavioral interventions for antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 22, 1–15.

Capaldi, D. M., Crosby, L., & Stoolmiller, M. (1996). Predicting the timing of first sexual intercourse for at-risk adolescent males. Child Development, 67, 344–359.

Connor, D. F., Doerfler, L. A., Toscanto, P. F., Volungis, A. M., & Steingard, R. J. (2004). Characteristics of children and adolescents admitted to a residential treatment center. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13, 497–510.

Corrigan, P. W., Steiner, L., McCracken, S. G., Blaser, B., & Barr, M. (2001). Strategies for disseminating evidence-based practices to staff who treat people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 52, 1598–1606.

Cunningham, S., Duffee, D. E., Huang, Y., Steinke, C., & Naccarato, T. (2009). On the meaning and measurement of engagement in youth residential treatment centers. Research on Social Work Practice, 19, 63–76.

Dodge, K. A., & Frame, C. L. (1982). Social cognitive biases and deficits in aggressive boys. Child Development, 53, 620–635.

Dozois, D. J., Westra, H. A., & Collins, K. A. (2004). Stages of change in anxiety: Psychometric properties of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA) scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(6), 711–723.

D’Zurilla, T. J., & Nezu, A. (1990). Development and preliminary evaluation of the social problem solving inventory. Psychological Assessment, 2, 156–163.

D’Zurilla, T. J., & Sheedy, C. F. (1991). Relation between social problem-solving ability and subsequent level of psychological stress in college students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 841–846.

Ellis, A., & Grieger, R. (1977). Handbook of rational-emotive therapy. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc.

Guterman, N. B., & Blythe, B. J. (1986). Toward ecologically based intervention in residential treatment for children. The Social Service Review, 60, 633–643.

Hair, H. J. (2005). Outcomes for children and adolescents after residential treatment: A review of research from 1993 to 2003. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14, 551–575.

Hoagwood, K., & Cunningham, M. (1992). Outcomes of children with emotional disturbance in residential treatment for educational purposes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 1, 129–140.

Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1986). The development of the working alliance inventory. In L. S. Greenberg & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 529–556). New York: Guilford.

Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). The development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 223–233.

Jaffee, W. B., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2003). Adolescent problem solving, parent problem solving, and externalizing behavior in adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 34, 295–311.

Kazdin, A. E., Bass, D., Siegel, T., & Thomas, C. (1989). Cognitive–behavioral therapy and relationship therapy in the treatment of children referred for antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 522–535.

Kazdin, A. E., & Crowley, M. J. (1997). Moderators of treatment outcome in cognitively based treatment in antisocial children. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 21, 185–207.

Knorth, E. J., Harder, A. T., Zandberg, T., & Kendrick, A. J. (2008). Under one roof: A review and selective meta-analysis on the outcomes of residential child and youth care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 123–140.

Leichtman, M., Leichtman, M. L., Cornsweet Barber, C., & Neese, D. T. (2001). Effectiveness of intensive short-term residential treatment with severely disturbed adolescents. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71, 227–235.

Lipsey, M. W. (1995). What do we learn from 400 research studies on the effectiveness of treatment with juvenile delinquents? In J. McGuire (Ed.), What works: Reducing reoffending: Guidelines from research and practice (pp. 63–78). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Lochman, J. E., Burch, P. R., Curry, J. F., & Lampron, L. B. (1984). Treatment and generalization effects of cognitive behavioral and goal setting interventions with aggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 915–916.

Lochman, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). Social-cognitive processes of severely violent, moderately aggressive, and nonaggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 366–374.

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 438–450.

McClintock, C. (1984). Toward a theory of formative program evaluation. In D. C. Cordray & M. W. Lipsey (Eds.), Evaluation studies review annual (Vol. 11, pp. 205–223). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

McConnaughy, E. A., Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. (1983). Stages of change in psychotherapy: Measurement and sample profiles. Psychotherapy, 20, 368–375.

McCurdy, B. L., Ludwikowski, C., & Mannella, M. (2000). The professionalization of direct care staff. In H. A. Savin & S. S. Kiesling (Eds.), Accountable systems of behavioral health care: A provider’s guide (pp. 97–112). San Francisco: Jossy-Bass.

McCurdy, B. L., & McIntyre, E. K. (2004). “And what about residential…?” Re-conceptualizing residential treatment as a stop-gap service for youth with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Interventions, 19, 137–158.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Orobio de Castro, B. O., Merk, W., & Koops, W. (2005). Emotions in social information processing and their relations with reactive and proactive aggression in referred aggressive boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 105–116.

Patton, M. Q. (1989). A context and boundaries for a theory-driven approach to validity. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12, 375–377.

Pogarsky, G., Lizotte, A. J., & Thornberry, T. P. (2003). The delinquency of children born to youth mothers: Results from the Rochester Youth Development Study. Criminology, 42, 1249–1286.

Prochaska, J. O., Diclemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102–1114.

Quiggle, N. L., Garber, J., Panak, W. F., & Dodge, K. A. (1992). Social information processing in aggressive and depressed children. Child Development, 63, 1305–1320.

Rabiner, D., Lenhart, L., & Lochman, J. E. (1990). Automatic versus reflective social problem solving in relation to children’s sociometric status. Developmental Psychology, 26, 1010–1016.

Richard, B. A., & Dodge, K. A. (1982). Social maladjustment and problem solving in school aged children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 226–233.

Rodriguez-Fornells, A., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (1999). Impulsive/careless problem solving style as predictor of subsequent academic achievement. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 639–645.

Ronan, K., & Kendall, P. (1990). Non-self-controlled adolescents: Applications of cognitive–behavioral therapy. In S. C. Feinstein, A. H. Esman, J. G. Looney, G. H. Orvin, & J. L. Schimel (Eds.), Adolescent psychiatry: Developmental and clinical studies (pp. 479–505). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rossi, P. H., Lipsey, M. W., & Freeman, H. E. (2004). Evaluation: A systematic approach (7th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shirk, S., & Karver, M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 462–471.

Shirk, S., & Karver, M. (2006). Process issues in cognitive–behavioral therapy for youth. In P. C. Kendall (Ed.), Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive–behavioral procedures (pp. 465–491). New York: Guilford Press.

Shure, M. B., & Spivack, G. (1972). Means-end thinking, adjustment, and social class among elementary-school-aged children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 38, 348–353.

Shure, M. B., Spivack, G., & Jaeger, M. (1971). Problem-solving thinking and adjustment among disadvantaged preschool children. Child Development, 42, 1791–1803.

Smith, B. D., Duffee, D. E., Steinke, C. M., Huang, Y., & Larkin, H. (2008). Outcomes in residential treatment for youth: The role of early engagement. Children and Youth Services Review. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.04.010.

Smith, K. J., Subich, L. M., & Kalodner, C. (1995). The transtheoretical models’ stages and processes of change and their relations to premature termination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 34–39.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA). (n.d.). Smoking: URICA (Long Form). Retrieved May 22, 2007, from http://www.uri.edu/research/cprc/Measures/Smoking04urica.htm.

Williams, S., Waymouth, M., & Lipman, E. (2004). Evaluation of a children’s temper-taming program. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49, 607–612.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants JJ99430000, JJ01430002 and J01430003 for “Initiating a Continual Improvement Process in Residential Educational Institutions for Youth,” from the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, Office of Funding and Program Assistance, Juvenile Justice Unit. Points of view presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the NYS Division of Criminal Justice Services. The authors thank the staff and clients at St. Anne and LaSalle for their participation in this study. We also extend our appreciation to David Duffee, Yufan Huang, and Dana Peterson for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1: Measurement Information

Appendix 1: Measurement Information

Measures for Which Factor and Reliability Analyses are Inappropriate

Problem-Solving Youth Wave 1

How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? (7-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree)

-

When I do not reach an answer to a problem the first time, I persist in seeking solutions.

Academic Achievement Youth Wave 1

Looking at all your grades last term, would you say you were closest to

-

Straight A student

-

B student

-

C student

-

D student, or an

-

F student?

-

Something else? Specify

Youth Violent Behavior Youth Wave 1

In the last 3 months have you…

-

Carried a hidden weapon?

-

Damaged, destroyed, or marked up somebody else’s property on purpose?

-

Set fire on purpose or tried to set fire to a house, building, or car?

-

Hit someone with the idea of hurting them (other than what you have already mentioned)?

-

Thrown objects such as rocks or bottles at people (other than what you have already mentioned)?

Measurement Items and Reliability Analyses

Problem-Solving Youth Wave 3 (α = .79)

How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? (7-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree)

-

After I try to solve a problem with a certain course of action, I take time and compare the actual result to what I thought would happen.

-

After I solve a problem, I try to figure out what went right and what went wrong.

-

When making a decision, I think about all the different things I might do and compare how each of them might turn out.

Psychological Symptoms Youth Wave 1 (α = .85)

How often in last month do you remember… (7-point scale from not at all to always)

-

Feeling overtired?

-

Being nervous or worried?

-

Feeling low or depressed?

-

Being tense or irritable?

-

Having trouble sleeping?

-

Losing your appetite?

-

Feeling apart or alone?

-

Feeling as if you were eating too much?

Youth Engagement in Treatment Youth Wave 2 (α = .92)

To what extent do you disagree or agree with the following statements? (7-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree)

-

I guess I have faults, but there’s nothing I really need to change.

-

Being here is pretty much a waste of time because I don’t have any problems that need to be changed.

-

Maybe this place will be able to help me.

-

I hope that someone here will have some good advice for me.

-

I am hoping that this place will help me to understand myself better.

-

I am finally doing some work on my problems.

-

I feel that staff here care about me even when I do things that they do not approve of.

-

I believe that staff here like me.

-

I feel that staff members here appreciate me—they really get me as a person.

-

Staff here understands my situation and my problems.

-

Staff here is genuinely concerned about my welfare.

-

I trust the staff here.

-

The staff here trust me.

-

Staff and I are working towards goals we agree on.

-

I have established a good understanding with the staff here of the kind of changes that would be good for me.

-

Staff and I agree on what is important for me to work on.

-

I am clear on what my responsibilities are around here, especially with regard to my work with my caseworker and counselors.

-

I sometimes wish the staff could better clarify the purpose of the counseling sessions here.

Youth Engagement in Treatment Staff Wave 2 (Clinician α = .95; Child Care α = .96)

To what extent do you disagree or agree with the following statements? (7-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree)

-

This youth thinks he/she has some faults, but nothing that he/she really needs to change.

-

This youth thinks being here is pretty much a waste of time, he/she doesn’t think he/she has any problems that need to be changed.

-

This youth thinks maybe this place will be able to help him/her.

-

This youth thinks that someone here may have some good advice for him/her.

-

This youth thinks that this place will help him/her to better understand himself/herself.

-

This youth is finally doing some work on his/her problems.

-

The youth feels staff here cares about him/her even when he/she does things that staff do not approve of.

-

This youth feels staff here like him/her.

-

This youth feels staff members here appreciate him/her- they really get him/her as a person.

-

This youth feels staff here understand his/her situation and problems.

-

This youth feels staff members here are genuinely concerned for his/her welfare.

-

This youth and staff have been working towards mutually agreed upon goals.

-

This youth has established a good understanding with the staff here of the kind of changes that would be good for him/her.

-

This youth has agreed with staff on what has been important for him/her to work on.

-

This youth is clear on what his/her responsibilities are around here, especially with regard to his/her work with his/her therapists/case managers.

Cognitive and Behavioral Disputations Wave 2 (Youth α = .93; Child Care α = .92; Clinician α = .97)

How often do staff… (7-point scale from not at all to always)

-

Help you think of different ways of doing things?

-

Ask you why you make some of the choices you do?

-

Ask you to think about how your actions affect others?

-

Ask you to think before you act?

-

Ask you to think about why something didn’t turn out like you expected?

-

Ask you to think about the costs and benefits of doing something?

-

Ask you to think twice about your actions and responses to trouble?

-

Bring it to your attention when you think or act in negative ways?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raftery, J.N., Steinke, C.M. & Nickerson, A.B. Engagement, Residential Treatment Staff Cognitive and Behavioral Disputations, and Youths’ Problem-Solving. Child Youth Care Forum 39, 167–185 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9093-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-010-9093-7