Abstract

Purpose

Low-dose aspirin (ASA) increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal (GI) complications. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce these upper GI side effects, yet patient compliance to PPIs is low. We determined the cost-effectiveness of gastroprotective strategies in low-dose ASA users considering ASA and PPI compliance.

Methods

Using a Markov model we compared four strategies: no medication, ASA monotherapy, ASA+PPI co-therapy and a fixed combination of ASA and PPI for primary and secondary prevention of ACS. The risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), upper GI bleeding and dyspepsia was modeled as a function of compliance and the relative risk of developing these events while using medication. Costs, quality adjusted life years and number of ACS events were evaluated, applying a variable risk of upper GI bleeding. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed.

Results

For our base case patients using ASA for primary prevention of ACS no medication was superior to ASA monotherapy. PPI co-therapy was cost-effective (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER] €10,314) compared to no medication. In secondary prevention, PPI co-therapy was cost-effective (ICER €563) while the fixed combination yielded an ICER < €20,000 only in a population with elevated risk for upper GI bleeding or moderate PPI compliance. PPI co-therapy had the highest probability to be cost-effective in all scenarios. PPI use lowered the overall number of ACS.

Conclusions

Considering compliance, PPI co-therapy is likely to be cost-effective in patients taking low dose ASA for primary and secondary prevention of ACS, given low PPI prices. In secondary prevention, a fixed combination seems cost-effective in patients with elevated risk for upper GI bleeding or in those with moderate PPI compliance. Both strategies reduced the number of ACS compared to ASA monotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86.

Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–60.

De Gaetano G. Low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in people at cardiovascular risk: a randomised trial in general practice. Collaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project. Lancet. 2001;357:89–95.

Coons JC, Battistone S. 2007 Guideline update for unstable angina/non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: focus on antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:989–1001.

Wolff T, Miller T, Ko S. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann. Intern. Med. 150:405–10.

Abraham NS, Hlatky MA, Antman EM, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 expert consensus document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2533–49.

McQuaid KR, Laine L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of adverse events of low-dose aspirin and clopidogrel in randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2006;119:624–38.

Garcia Rodriguez LA, Lin KJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with low-dose acetylsalicylic acid alone and in combination with clopidogrel and other medications. Circulation. 2011;123:1108–15.

Earnshaw SR, Scheiman J, Fendrick AM, et al. Cost-utility of aspirin and proton pump inhibitors for primary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:218–25.

Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM, et al. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2033–8.

Lanas A, Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Arroyo MT, et al. Effect of antisecretory drugs and nitrates on the risk of ulcer bleeding associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulants. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:507–15.

Scheiman J, Herlitz J, Agewall S, et al. Esomeprazole 20 mg and 40 mg for 26 weeks reduces the frequency of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in patients taking low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for cardiovascular prevention: The OBERON trial. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:674–4.

Yeomans N, Lanas A, Labenz J, et al. Efficacy of esomeprazole (20 mg once daily) for reducing the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with continuous use of low-dose aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2465–73.

Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Fendrick AM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitor cotherapy in patients taking long-term, low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1684–90.

Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2667–74.

Herlitz J, Toth PP, Naesdal J. Low-dose aspirin therapy for cardiovascular prevention: quantification and consequences of poor compliance or discontinuation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010;10:125–41.

Garcia-Rodriguez LA, Johansson S, Martin-Merino E. Impact of gastrointestinal disease on the risk of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid discontinuation. Gastroenterology. 2011;140, supplement 1: S-585.

Moberg C, Naesdal J, Svedberg LE, et al. Impact of gastrointestinal problems on adherence to low-dose acetylsalicylic Acid: a quantitative study in patients with cardiovascular risk. Patient. 2011;4:103–13.

Herlitz J, Sorstadius E, Naucler E, et al. Prescription rates and adherence to proton pump inhibitor therapy among patients who require low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for cardiovascular prevention. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:675–6.

van Soest EM, Valkhoff VE, Mazzaglia G, et al. Suboptimal gastroprotective coverage of NSAID use and the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and ulcers: an observational study using three European database. Gut. 2011;60:1650–9.

Goldstein JL, Hochberg MC, Fort JG, et al. Clinical trial: the incidence of NSAID-associated endoscopic gastric ulcers in patients treated with PN 400 (naproxen plus esomeprazole magnesium) vs. enteric-coated naproxen alone. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:401–13.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Wilson PW, Larson MG, et al. Framingham risk score and prediction of lifetime risk for coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:20–4.

Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1706–17.

Fox KA, Carruthers KF, Dunbar DR, et al. Underestimated and under-recognized: the late consequences of acute coronary syndrome (GRACE UK-Belgian Study). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2755–64.

Wang TH, Bhatt DL, Fox KA, et al. An analysis of mortality rates with dual-antiplatelet therapy in the primary prevention population of the CHARISMA trial. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2200–7.

Thrombosis prevention trial: randomised trial of low-intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. The Medical Research Council’s General Practice Research Framework. Lancet. 1998;351:233–41.

Weisman SM, Graham DY. Evaluation of the benefits and risks of low-dose aspirin in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2197–202.

Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909–17.

Lanas A, Wu P, Medin J, et al. Low doses of acetylsalicylic acid increase risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:762–8.

Statistics Netherlands. Chances of death tables. Available at http://statline.cbs.nl. 2011.

Hernandez-Diaz S, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Cardioprotective aspirin users and their excess risk of upper gastrointestinal complications. BMC Med. 2006;4:22.

Huang ES, Strate LL, Ho WW, et al. A prospective study of aspirin use and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in men. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15721.

van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494–9.

Masso Gonzalez EL, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the long-term risk of recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding: an observational study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:629–37.

Ng W, Wong WM, Chen WH, et al. Incidence and predictors of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients receiving low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2923–7.

Shalev A, Zahger D, Novack V, et al. Incidence, predictors and outcome of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Int J Cardiol. 2012;157:386–90.

Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, et al. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222–6.

Straube S, Tramer MR, Moore RA, et al. Mortality with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation: effects of time and NSAID use. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:41.

Berger JS, Roncaglioni MC, Avanzini F, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women and men: a sex-specific meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295:306–13.

Goldberg RJ, Currie K, White K, et al. Six-month outcomes in a multinational registry of patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome (the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events [GRACE]). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:288–93.

Hochholzer W, Buettner HJ, Trenk D, et al. New definition of myocardial infarction: impact on long-term mortality. Am J Med. 2008;121:399–405.

Perers E, Caidahl K, Herlitz J, et al. Treatment and short-term outcome in women and men with acute coronary syndromes. Int J Cardiol. 2005;103:120–7.

Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502.

Health Care Insurance Board. Available at www.medicijnkosten.nl. May 2011.

Groeneveld PW, Lieu TA, Fendrick AM, et al. Quality of life measurement clarifies the cost-effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori eradication in peptic ulcer disease and uninvestigated dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:338–47.

Latimer N, Lord J, Grant RL, et al. Cost effectiveness of COX 2 selective inhibitors and traditional NSAIDs alone or in combination with a proton pump inhibitor for people with osteoarthritis. BMJ. 2009;339:b2538.

Kim J, Henderson RA, Pocock SJ, et al. Health-related quality of life after interventional or conservative strategy in patients with unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: one-year results of the third Randomized Intervention Trial of unstable Angina (RITA-3). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:221–8.

Sullivan PW, Slejko JF, Sculpher MJ, et al. Catalogue of EQ-5D scores for the United Kingdom. Med Dec Making. 2011;31:800–4.

Tsevat J, Goldman L, Soukup JR, et al. Stability of time-tradeoff utilities in survivors of myocardial infarction. Med Dec Making. 1993;13:161–5.

Newby LK, LaPointe NM, Chen AY, et al. Long-term adherence to evidence-based secondary prevention therapies in coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2006;113:203–12.

Kulkarni SP, Alexander KP, Lytle B, et al. Long-term adherence with cardiovascular drug regimens. Am Heart J. 2006;151:185–91.

Kronish IM, Rieckmann N, Shimbo D, et al. Aspirin adherence, aspirin dosage, and C-reactive protein in the first 3 months after acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1090–4.

Pratt S, Thompson VJ, Elkin EP, et al. The impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms on nonadherence to, and discontinuation of, low-dose acetylsalicylic acid in patients with cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010;10:281–8.

Sturkenboom MC, Burke TA, Tangelder MJ, et al. Adherence to proton pump inhibitors or H2-receptor antagonists during the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1137–47.

van der Linden MW, Gaugris S, Kuipers EJ, et al. Gastroprotection among new chronic users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a study of utilization and adherence in The Netherlands. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:195–204.

Van Soest EM, Siersema PD, Dieleman JP, et al. Persistence and adherence to proton pump inhibitors in daily clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:377–85.

Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Tan SS, Bouwmans CAM. Manual for cost research, methods and standard cost prices for economic evaluations in health care (Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek, methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg). Health Care Insurance Board. Actualized version 2010. 2010.

Greving JP, Buskens E, Koffijberg H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of aspirin treatment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events in subgroups based on age, gender, and varying cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2008;117:2875–83.

Aro P, Talley NJ, Agreus L, et al. Functional dyspepsia impairs quality of life in the adult population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1215–24.

Laheij RJ, Van Rossum LG, Krabbe PF, et al. The impact of gastrointestinal symptoms on health status in patients with cardiovascular disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:881–5.

Laheij RJ, Jansen JB, Verbeek AL, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection as a risk factor for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients using aspirin to prevent ischaemic heart disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1055–9.

Silagy CA, McNeil JJ, Donnan GA, et al. Adverse effects of low-dose aspirin in a healthy elderly population. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54:84–9.

Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, et al. The efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1329–37.

Saini SD, Fendrick AM, Scheiman JM. Cost-effectiveness analysis: cardiovascular benefits of proton pump inhibitor co-therapy in patients using aspirin for secondary prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:243–51.

Annemans L, Wittrup-Jensen K, Bueno H. A review of international pharmacoeconomic models assessing the use of aspirin in primary prevention. J Med Econ. 2010;13:418–27.

Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1293–304.

Flossmann E, Rothwell PM. Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomised and observational studies. Lancet. 2007;369:1603–13.

McCarthy DM. Adverse effects of proton pump inhibitor drugs: clues and conclusions. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:624–31.

Yang YX, Metz DC. Safety of proton pump inhibitor exposure. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1115–27.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by an unrestricted educational grant from AstraZeneca.

Conflicts of Interest

The salary of N.L. de Groot is paid by an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca. HGM van Haalen reports no conflicts of interest during the conduction of this research project. She currently works for AstraZeneca. BMR Spiegel has received unrestricted research grant support from Movetis and serves as an advisor for AstraZeneca. L. Laine serves as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Eisai, Horizon, and Pfizer and joins the Safety Monitoring Board for Bayer, Merck and BMS. A. Lanas serves as an advisor for AstraZeneca and Bayer. J. Jaspers Focks reports no conflicts of interest. PD Siersema received unrestricted research grant support from AstraZeneca, Movetis and Janssen, and serves as an advisor for Pfizer, Janssen and Movetis. MGH van Oijen received unrestricted grant support from AstraZeneca and Janssen, and serves as an advisor for AstraZeneca and Pfizer.

Contributorship Statement

HGM van Haalen: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, statistical analysis; NL de Groot: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, statistical analysis; BMR Spiegel: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision; L Laine: interpretation of data, critical revision; A Lanas: interpretation of data, critical revision; J Jaspers Focks: interpretation of data, critical revision; PD Siersema: interpretation of data, critical revision, study supervision; MGH van Oijen: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, statistical analysis, study supervision

By Dutch law, this protocol did not need approval by the Ethical Review Board as no identifiable patient data were used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

N. L. de Groot and H. G. M. van Haalen contributed equally to this paper.

Technical Appendix

Technical Appendix

Input Parameters

We performed a structured search using PubMed and Embase databases limiting our results to English language and using combinations of relevant entry terms (aspirin, proton pump inhibitor, gastrointestinal, acute coronary syndrome, prevention, compliance, adherence, incidence, risk, relative risk, cost-effectiveness). Where available, we used meta-analyses or systematic reviews reporting intention-to-treat summary estimates. In order to derive annual transition probabilities, we multiplied placebo risks (on the development of ACS, upper GI bleeding and dyspepsia) by the relative risks of aspirin and, if necessary, PPI. In case placebo risks were unknown, we divided the risk with aspirin monotherapy by the relative risk of aspirin. Utility values of the combined health states for which no data was available (e.g. Post ACS+dyspepsia) were derived by multiplying the separate utilities of the involved health states (Table 4).

Model Assumptions

-

1)

A patient who develops dyspepsia visited his/her primary care provider and received a 4 week trial of PPI therapy (omeprazole 20 mg daily). Patients previously treated with PPIs were assumed to be given a dose of 40 mg/day. Should this be ineffective (approximately 45 % of patients), the patient is referred to a gastroenterologist. The patient receives diagnostic endoscopy including a H.pylori test. H.Pylori eradication therapy is given if appropriate, and eradication is confirmed by a breath test. Patients receive another 8 weeks of PPI therapy and are assumed to visit their primary care provider a total of three times per year.

-

2)

All patients with persistent dyspepsia receive PPI therapy. Patients who were allocated to no medication or aspirin monotherapy receive 20 mg PPI daily during the complete cycle, whereas patients who were allocated aspirin+PPI or a single tablet formulation receive additional PPI (40 mg omeprazole daily in total). All patients are assumed to visit their primary care provider annually.

-

3)

Patients who develop an upper GI bleeding are admitted to the hospital after reporting to the emergency department. Sixty percent of patients need a blood transfusion and all receive endoscopic therapy, intravenous PPI, H.pylori testing and H.pylori eradication therapy plus breath test confirmation if necessary. A second therapeutic endoscopy is performed in case of therapy failure, followed by percutaneous embolization if therapeutic endoscopy remains unsuccessful. A second look endoscopy is performed in patients with an ulcus ventriculi. The average duration of hospitalization is 10 days. At discharge all patients receive PPI therapy for the remainder of the time horizon: 20 mg omeprazole in case the patient was allocated to no medication or aspirin monotherapy and 40 mg omeprazole in case the patients was allocated aspirin+PPI or a single tablet formulation. Patients allocated to the single tablet formulation continue their assigned medication and are prescribed an additional 20 mg PPI (instead of changing to 40 mg PPI concomitant to low-dose aspirin). In case of primary prevention of ACS, low-dose aspirin therapy is interrupted for 1 year. Patients are assumed to visit the outpatient clinic once in the following year. During the first year, 6.7 % of patients experiences a rebleeding.

-

4)

Patients experiencing an ACS report to the emergency department where an ECG is made and cardiac marker levels (including troponin) are determined. We assumed that coronary angiography is performed in 90 % of patients, whereas 70 % of patients receive an additional percutaneous intervention and 5 % of patients require coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. In hospital, all patients receive low-dose aspirin and β-blockers, and some patients receive clopidogrel (60 %), ACE-inhibitors (55 %), nitroglycerin (70 %) and heparin (35 %). The average duration of hospitalization is 5 days. At discharge, all patients receive low-dose aspirin. In addition, patients receive β-blockers, statins and ACE-inhibitors for the remainder of the time horizon, whereas 80 % also receive clopidogrel for 1 year. During the first year rehospitalization is necessary in 30 % of patients. Patients are assumed to visit the outpatient clinic four times during the first year and once annually thereafter

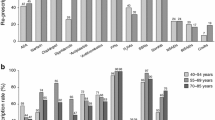

Probability distributions of compliance. N.B. The compliance to the single tablet formulation before complications have occurred, was assumed to equal the compliance to aspirin before complications have occurred. The compliance to the single tablet formulation after ACS or GI complications, was assumed to equal the compliance to aspirin after an ACS

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Groot, N.L., van Haalen, H.G.M., Spiegel, B.M.R. et al. Gastroprotection in Low-Dose Aspirin Users for Primary and Secondary Prevention of ACS: Results of a Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Including Compliance. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 27, 341–357 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-013-6448-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-013-6448-y