Abstract

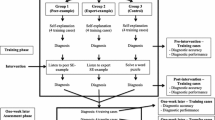

The present study aims at fostering undergraduate medical students’ clinical reasoning by learning from errors. By fostering the acquisition of “negative knowledge” about typical cognitive errors in the medical reasoning process, we support learners in avoiding future erroneous decisions and actions in similar situations. Since learning from errors is based on self-explanation activities, we provided additional prompting procedures to foster the effectiveness of the error-based instructional approach. The extent of instructional support in a web-based learning environment with erroneous clinical case examples was varied in a one-factorial design with three groups by either presenting the cases as (a) unsupported worked examples or by providing the participants with (b) closed prompts in the form of multiple-choice tasks or (c) with open reflection prompts during the learning process. Despite significant learning progress in all conditions, neither prompting procedure improved the learning outcomes beyond the level of the unsupported worked example condition. In contrast to our hypotheses, the unsupported worked example condition was the most effective with respect to fostering clinical reasoning performance. The effects of the learning conditions on clinical reasoning performance was mediated by cognitive load, and moderated by the students’ self-efficacy. Both prompting procedures increased extraneous cognitive load. For learners with low self-efficacy, the prompting procedures interfered with effective learning from errors. Although our error-based instructional approach substantially improved clinical reasoning, additional instructional measures intended to support error-based learning processes may overtax learners in an early phase of clinical expertise development and should therefore only be used in moderation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychology Review, 84, 191–215.

Berner, E. S., & Graber, M. L. (2008). Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. American Journal of Medicine, 121, 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.001.

Berthold, K., Eysink, T. H. S., & Renkl, A. (2009). Assisting self-explanation prompts are more effective than open prompts when learning with multiple representations. Instructional Science, 37(4), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-008-9051-z.

Berthold, K., & Renkl, A. (2009). Instructional aids to support a conceptual understanding of multiple representations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(1), 70–87.

Boekaerts, M. (2006). Self-regulation and effort investment. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., pp. 345–377). New York: Wiley.

Booth, J. L., Lange, K. E., Koedinger, K. R., & Newton, K. J. (2013). Using example problems to improve student learning in algebra: Differentiating between correct and incorrect examples. Learning and Instruction, 25, 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.11.002.

Bordage, G., Brailovsky, C., Carretier, H., & Page, G. (1995). Content validation of key features on a national examination of clinical decision-making skills. Academic Medicine, 70(4), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199504000-00010.

Chamberland, M., Mamede, S., St-Onge, C., Rivard, M. A., Setrakian, J., Lévesque, A., et al. (2013). Students’ self-explanations while solving unfamiliar cases: The role of biomedical knowledge. Medical Education, 47(11), 1109–1116. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12253.

Chamberland, M., Mamede, S., St-Onge, C., Setrakian, J., Bergeron, L., & Schmidt, H. (2015a). Self-explanation in learning clinical reasoning: The added value of examples and prompts. Medical Education, 49(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12623.

Chamberland, M., Mamede, S., St-Onge, C., Setrakian, J., & Schmidt, H. G. (2015b). Does medical students’ diagnostic performance improve by observing examples of self-explanation provided by peers or experts? Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice., 4, 981–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-014-9576-7.

Chamberland, M., St-Onge, C., Setrakian, J., Lanthier, L., Bergeron, L., Bourget, A., et al. (2011). The influence of medical students’ self-explanations on diagnostic performance. Medical Education, 45(7), 688–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03933.x.

Charlin, B., Boshuizen, H. P. A., Custers, E. J., & Feltovich, P. J. (2007). Scripts and clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 41, 1178–1184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02924.x.

Coderre, S., Mandin, H., Harasym, P. H., & Fick, G. H. (2003). Diagnostic reasoning strategies and diagnostic success. Medical Education, 37(8), 695–703. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01577.x.

Cronbach, L. J., & Snow, R. E. (1977). Aptitudes and instructional methods. New York, NY: Irvington.

Croskerry, P. (2009). A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Academic Medicine, 84(8), 1022–1028.

Croskerry, P. (2013). From mindless to mindful practice—Cognitive bias and clinical decision-making. New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 2445–2448. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ace703.

Curry, L. (2004). The effects of self-explanations of correct and incorrect solutions on algebra problem solving performance. In K. Forbus, D. Gentner, & T. Regier (Eds.), Proceedings of the 26th annual conference of the cognitive science society (Vol. 1548). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Durkin, K., & Rittle-Johnson, B. (2012). The effectiveness of using incorrect examples to support learning about decimal magnitude. Learning and Instruction, 22, 206–214. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ace703.

Dyre, L., Tabor, A., Ringsted, C., & Tolsgaard, M. G. (2016). Imperfect practice makes perfect: Error management training improves transfer of learning. Medical Education, 51(2), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13208.

Endres, T., & Renkl, A. (2015). Mechanisms behind the testing effect: An empirical investigation of retrieval practice in meaningful learning. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.11.001.

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data (Revised ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavioral Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Greeno, J. G., Collins, A. M., & Resnick, L. B. (1996). Cognition and learning. In D. Berliner & R. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 15–41). New York: MacMillian.

Hausmann, R. G. M., & VanLehn, K. (2007). Explaining self-explaining: A contrast between content and generation. In R. Luckin, K. R. Koedinger, & J. Greer (Eds.), Artificial intelligence in education: Building technology rich learning contexts that work (Vol. 158, pp. 417–424). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Heitzmann, N., Fischer, F., & Fischer, M. (2013). When error-explanation prompts and adaptable feedback cannot support the learning of diagnostic competence. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (AERA) “Education and Poverty: Theory, Research, Policy, and Praxis”, San Francisco, April 27–May 1, 2013.

Jerusalem, M., & Schwarzer, R. (1999). Allgemeine Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung [General self-efficacy expectation]. In R. Schwarzer & M. Jerusalem (Eds.), Skalen zur Erfassung von Lehrer- und Schülermerkmalen [scales for the assessment of teacher and student characteristics] (pp. 13–14). Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin.

Kirschner, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86.

Klein, M., Kopp, V., Fischer, M. R., & Stark, R. (accepted). Think aloud protocols in medical education: An assessment of the diagnostic approach and handling of instructional errors in experts and novices. In E. Klopp, J. F. Schneider & R. Stark (Eds.), Thinking aloud: The mind in action.

Klein, M., Wagner, K., Klopp, E., & Stark, R. (2015). Förderung anwendbaren bildungswissenschaftlichen Wissens bei Lehramtsstudierenden anhand fehlerbasierten kollaborativen Lernens: Eine Studie zur Replikation bisheriger Befunde sowie zur Nachhaltigkeit und Erweiterung der Trainingsmaßnahmen [Fostering of applicable educational knowledge in student teachers by error-based collaborative learning: Replication of findinds and extension of the training intervention]. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 43(3), 225–244.

Klopp, E., Stark, R., Kopp, V., & Fischer, M. R. (2013). Psychological factors affecting medical students’ learning with erroneous worked examples. Journal of Education and Learning, 2(1), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v2n1p158.

Kolodner, J. L. (2006). Case-based reasoning. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 225–242). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

La Rochelle, J. S., Durning, S. J., Pangaro, L. N., Artino, A. R., Van der Vleuten, C. P. M., & Schuwirth, L. (2011). Authenticity of instruction and student performance: A prospective randomised trial. Medical Education, 45, 807–817.

Lanubile, F., Shull, F., & Basili, V. R. (1998). Experimenting with error abstraction in requirements documents. In Proceedings of fifth international symposium software metrics (pp. 114–121). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/METRIC.1998.731236.

Larsen, D. P., Butler, A. C., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). Test-enhanced learning in medical education. Medical Education, 42(10), 959–966.

Lawson, A. E., & Daniel, E. S. (2011). Inferences of clinical diagnostic reasoning and diagnostic error. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 44, 402–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2010.01.003.

Mamede, S., Schmidt, H. G., & Rikers, R. (2007). Diagnostic errors and reflective practice in medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13(1), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2010.01.003.

Mayer, R. E. (2005). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 31–48). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Moreno, R. (2010). Cognitive load theory: More food for thought. Instructional Science, 38(2), 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2010.01.003.

Oser, F. (2007). Aus Fehlern lernen [learning from errors]. In M. Göhlich, Ch. Wulf, & J. Zirfas (Eds.), Pädagogische Theorien des Lernens [Pedagogical learning theories] (pp. 203–212). Weinheim: Beltz.

Oser, F., & Spychiger, M. (2005). Lernen ist schmerzhaft. Zur Theorie des Negativen Wissens und zur Praxis der Fehlerkultur [Learning is painful. On the theory of negative knowledge and the practice of error culture]. Weinheim: Beltz.

Paas, F., & Kalyuga, S. (2005). Cognitive measurements to design effective learning environments. Paper presented at the International Workshop and Mini-conference on Extending Cognitive Load Theory and Instructional Design to the Development of Expert Performance. Heerlen, The Netherlands.

Paas, F., & Kirschner, F. (2012). The goal-free effect. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning (pp. 1375–1377). Berlin: Springer.

Paas, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2003). Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 1–4.

Paris, S., Lipson, M., & Wixson, K. (1983). Becoming a strategic reader. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8(3), 293–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476X(83)90018-8.

Patel, V. L., Arocha, J. F., & Zhang, J. (2012). Medical reasoning and thinking. In: The Oxford handbook of thinking and reasoning. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734689.013.0037.

Renkl, A. (1997). Intrinsic motivation, self-explanations, and transfer. München: Universität, Institut für Pädagogische Psychologie und Empirische Pädagogik.

Renkl, A. (1999). Learning mathematics from worked-out examples: Analyzing and fostering self-explanations. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 14(4), 477–488.

Renkl, A. (2014). Toward an instructionally oriented theory of example-based learning. Cognitive Science, 38(1), 1–37.

Renkl, A., & Atkinson, R. K. (2010). Learning from worked-out examples and problem solving. In J. L. Plass, R. Moreno, & R. Brünken (Eds.), Cognitive load theory (pp. 91–108). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rikers, R. M. J. P., Schmidt, H. G., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2000). Knowledge encapsulation and the intermediate effect. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1998.1000.

Schmidmaier, R., Ebersbach, R., Schiller, M., Hege, I., Holzer, M., & Fischer, M. R. (2011). Using electronic flashcards to promote learning in medical students: Retesting versus restudying. Medical Education, 45(11), 1101–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04043.x.

Schnell, K., Ringeisen, T., Raufelder, D., & Rohrmann, S. (2015). The impact of adolescents’ self-efficacy and self-regulated goal attainment processes on school performance—Do gender and test anxiety matter? Learning and Individual Differences, 38, 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.12.008.

Seufert, T., Schütze, M., & Brünken, R. (2009). Memory characteristics and modality in multimedia learning: An aptitude-treatment-interaction study. Learning and Instruction, 19, 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1998.1000.

Simmons, B. (2010). Clinical reasoning: Concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66, 1151–1158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05262.x.

Simonsohn, A. B., & Fischer, M. R. (2004). Evaluation of a case-based computerized learning program (CASUS) for medical students during their clinical years. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift, 129, 552–556.

Stark, R., Kopp, V., & Fischer, M. (2011). Case-based learning with worked examples in complex domains: Two experimental studies in undergraduate medical education. Learn Instruc, 21(1), 22–33.

Stark, R., Mandl, H., Gruber, H., & Renkl, A. (2002). Conditions and effects of example elaboration. Learning and Instruction, 12, 39–60.

Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous and germane cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 22, 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9128-5.

Sweller, J., van Merriёnboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10, 251–296.

Thammasitboon, S., & Cutrer, W. B. (2013). Diagnostic decision-making and strategies to improve diagnosis. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 43, 232–241.

Van de Wiel, M. W. J., Boshuizen, H. P. A., & Schmidt, H. G. (2000). Knowledge structuring in expertise development: Evidence from pathophysiological representations of clinical cases by students and physicians. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 12(3), 323–355.

VanLehn, K., Siler, S., Murray, R. C., Yamauchi, T., & Baggett, W. B. (2003). Why do only some events cause learning during human tutoring? Cognition and Instruction, 21, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532690XCI2103_01.

Vollmeyer, R., & Burns, B. D. (2002). Goal specificity and learning with a hypermedia program. Experimental Psychology, 49, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1027//1618-3169.49.2.98.

Wagner, K., Klein, M., Klopp, E., & Stark, R. (2014). Instruktionale Unterstützung beim Lernen aus advokatorischen Fehlern in der Lehramtsausbildung: Effekte auf die Anwendung wissenschaftlichen Wissens [Instructional support in learning from advocatory errors in teacher education: Effects on the application of scientific knowledge]. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 61, 287–301.

Walia, G. S., & Carver, J. C. (2013). Using error abstraction and classification to improve requirement quality: Conclusions from a family of four empirical studies. Empirical Software Engineering, 18(4), 625–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-012-9202-3.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532690XCI2103_01.

Funding

Funding was provided by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, German Research Foundation (Grant Nos. STA 596/7-1, FI720/6-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

This study was approved to comply with ethical standards by the Ethics Committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klein, M., Otto, B., Fischer, M.R. et al. Fostering medical students’ clinical reasoning by learning from errors in clinical case vignettes: effects and conditions of additional prompting procedures to foster self-explanations. Adv in Health Sci Educ 24, 331–351 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-09870-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-018-09870-5