Abstract

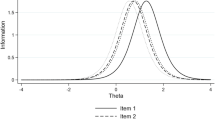

Physician–patient communication is a clinical skill that can be learned and has a positive impact on patient satisfaction and health outcomes. A concerted effort at all medical schools is now directed at teaching and evaluating this core skill. Student communication skills are often assessed by an Objective Structure Clinical Examination (OSCE). However, it is unknown what sources of error variance are introduced into examinee communication scores by various OSCE components. This study primarily examined the effect different examiners had on the evaluation of students’ communication skills assessed at the end of a family medicine clerkship rotation. The communication performance of clinical clerks from Classes 2005 and 2006 were assessed using six OSCE stations. Performance was rated at each station using the 28-item Calgary-Cambridge guide. Item Response Theory analysis using a Multifaceted Rasch model was used to partition the various sources of error variance and generate a “true” communication score where the effects of examiner, case, and items are removed. Variance and reliability of scores were as follows: communication scores (.20 and .87), examiner stringency/leniency (.86 and .91), case (.03 and .96), and item (.86 and .99), respectively. All facet scores were reliable (.87–.99). Examiner variance (.86) was more than four times the examinee variance (.20). About 11% of the clerks’ outcome status shifted using “true” rather than observed/raw scores. There was large variability in examinee scores due to variation in examiner stringency/leniency behaviors that may impact pass–fail decisions. Exploring the benefits of examiner training and employing “true” scores generated using Item Response Theory analyses prior to making pass/fail decisions are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adamson, T. E., & Gullion, D. S. (1984). Physician–patient communication and medical malpractice. Mobius, 4, 33–37.

Bass, E. B., Fortin, A. H., 4th, Morrison, G., Wills, S., Mumford, L. M., & Goroll, A. H. (1997). National survey of clerkship directors in internal medicine on the competencies that should be addressed in the medicine core clerkship. American Journal of Medicine, 102, 564–571.

Bond T. G., & Fox C. M. (2001). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurements in human sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers Mahwah.

Bowers, R. (1993). From lab tests to lawsuits: Improving physician–patient communication. TMA communications and public service committee. Journal of the Tennessee Medical Association, 86, 112.

Brown, G., Manogue, M., & Martin, M. (1999). The validity and reliability of an OSCE in dentistry. European Journal of Dental Education, 3, 117–125.

Candib, L. (1999). When the doctor takes off her clothes: Reflections on being seen by patients in the exercise setting. Families, Systems, & Health, 17, 349–363.

Cohen, R. (2001). Assessing professional behaviour and medical error. Medical Teacher, 23, 145–151.

Cohen, R., Reznick, R. K., Taylor, B. R., Provan, J., & Rothman, A. (1990). Reliability and validity of the objective structured clinical examination in assessing surgical residents. American Journal of Surgery, 160, 302–305.

Frymoyer, J. W., & Frymoyer, N. P. (2002). Physician–patient communication: A lost art? The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 10, 95–105.

Gordon, G. H., Baker, L., & Levinson, W. (1995). Physician–patient communication in managed care. The Western Journal of Medicine, 163, 527–531.

Hagihara, A., & Nobutomo, K. (2002). Physician–patient communication and malpractice claims. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi, 93, 79–84.

Herndon, J. H., & Pollick, K. J. (2002). Continuing concerns, new challenges, and next steps in physician–patient communication. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American, 84-A, 309–315.

Hodges, B., Turnbull, J., Cohen, R., Bienenstock, A., & Norman, G. (1996). Evaluating communication skills in the OSCE format: Reliability and generalizability. Medical Education, 30, 38–43.

Kurtz, S. M. (2002). Doctor–patient communication: Principles and practices. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, 29, S23–S29.

Kurtz, S, Silverman, J, & Draper, J. (2005). Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine (2nd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon, U.K.: Radcliffe Medical Press.

Lawson, D. M. (2003). Use of the multifaceted Rasch model to adjust for the error variance due to the examiner stringency-leniency effects in OSCEs. Masters Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary AB.

Lawson, D. M., & Harasym, P. H. (2003). Standardized patients: Their role in evaluating interexaminer reliability, consistency of performance of standardized patients and candidate anxiety on licensure examinations. Poster presented at the American Medical Association’s Research in Medical Education Conference (Washington DC). .

Levinson, W. (1994). Physician–patient communication. A key to malpractice prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 1619–1620.

Levinson, W., Roter, D. L., Mullooly, J. P., Dull, V. T., & Frankel, R. M. (1997). Physician–patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. Journal of the American Medical Association, 277, 553–559.

Linacre, J. M. (2006). Many-facet Rasch analysis. WINSTEPS® & Facets Rasch Software [On-line]. Retrieved November 22, 2006, from www.winsteps.com/facpass.htm.

Matsell, D. G., Wolfish, N. M., & Hsu, E. (1991). Reliability and validity of the objective structured clinical examination in paediatrics. Medical Education, 25, 293–299.

McManus, I. C., Thompson, M., & Mollon, J. (2006). Assessment of examiner leniency and stringency (‘hawk-dove effect’) in the MRCP(UK) clinical examination (PACES) using multi-facet Rasch modelling. BMC Medical Education, 6, 1272–1294.

Myford, C. M., & Wolfe, E. W. (2003). Detecting and measuring rater effects using many-facet Rasch measurement: Part I. Journal of Applied Measurement, 4, 386–422.

Myford, C. M., & Wolfe, E. W. (2004). Detecting and measuring rater effects using many-facet Rasch measurement: Part II. Journal of Applied Measurement, 5, 189–227.

Neuwirth, Z. E. (1999a). An essential understanding of physician-patient communication. Part I. The Journal of Medical Practice Management, 15, 14–18.

Neuwirth, Z. E. (1999b). An essential understanding of physician–patient communication. Part II. The Journal of Medical Practice Management, 15, 68–72.

Osler, W. (1913). Examinations, examiners and examinees. Lancet, 182, 1047–1050.

Peskin, T., Micklitsch, C., Quirk, M., Sims, H., & Primack, W. (1995). Malpractice, patient satisfaction, and physician–patient communication. Journal of the American Medical Association, 274, 22.

Petrusa, E. R., Blackwell, T. A., & Ainsworth, M. A. (1990). Reliability and validity of an objective structured clinical examination for assessing the clinical performance of residents. Archives of Internal Medicine, 150, 573–577.

Petrusa, E. R., Blackwell, T.A., Rogers, L.P., Sayjari, C., Parcel, S., & Guckian, J.C. (1987). An objective measure of clinical performance. American Journal of Medicine, 83, 34–42.

Regehr, G., Freeman, R., Hodges, B., & Russell, L. (1999). Assessing the generalizability of OSCE measures across content domains. Academic Medicine, 74, 1320–1322.

Robb, K., & Rothman, A.I. (1985). Assessment of clinical skills in general internal medicine residents - comparison of the objective structured clinical examination to a conventional oral examination. Annals of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 18, 235–238.

Scullen, S. E., Mount, M. K., & Goff, M. (2000). Understanding the latent structure of job performance ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 956–970.

Silverman, J., & Wood, D. F. (2004). New approaches to learning clinical skills. Medical Education, 38, 1021–1023.

Smith, R. M., & Miao, C. Y. (1994). Assessing unidimensionality for Rasch measurement. In M. Wilson (Ed.), Objective measurement: Theory into practice (Vol. 2). Greenwich: Ablex.

Starfield, B., Wray, C., Hess, K., Gross, R., Birk, P. S., & D’Lugoff, B. C. (1981). The influence of patient–practitioner agreement on outcome of care. American Journal of Public Health, 71, 127–131.

Statistica 6.0 (2001). [Computer software]. Tulsa OK: StatSoft Inc.

Stewart, M. A. (1995). Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: A review. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 152, 1423–1433.

Stewart, M. A., McWhinney, I. R., & Buck, C.W. (1979). The doctor/patient relationship and its effect upon outcome. The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 29, 77–82.

Valente, C. M., Antlitz, A. M., Boyd, M. D., & Troisi, A. J. (1988). The importance of physician–patient communication in reducing medical liability. Maryland Medical Journal, 37, 75–78.

Weyrauch, K. F. (1995). Malpractice, patient satisfaction, and physician-patient communication. Journal of the American Medical Association, 274, 22–23.

Workshop Planning Committee (1992). Consensus statement. Workshop on the Teaching and Assessment of Communication Skills in Canadian Medical Schools, 147, 1149–1152.

Zoppi, K., & Epstein, R. M. (2002). Is communication a skill? Communication behaviors and being in relation. Family Medicine, 34, 319–324.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

Initiating the session

-

1.

Greets patient,

-

2.

Introduces self and role,

-

3.

Demonstrates respect,

-

4.

Identifies and confirms problems list,

-

5.

Negotiates agenda

Gathering information

Exploration of problems:

-

6.

Encourages patient to tell story,

-

7.

Appropriately moves from open to closed questions,

-

8.

Listens attentively,

-

9.

Facilitates patient’s responses verbally & non-verbally,

-

10.

Uses easily understood questions and comments,

-

11.

Clarifies patient’s statements,

-

12.

Establishes dates

Understanding patient’s perspective:

-

13.

Determines and acknowledges patient’s ideas re cause,

-

14.

Explores patient’s concerns re problem,

-

15.

Encourages expression of emotions,

-

16.

Picks up verbal and non-verbal cues

Providing structure to consultation:

-

17.

Summarizes at end of a specific line of enquiry,

-

18.

Progresses using transitional statements,

-

19.

Structures logical sequence,

-

20.

Attends to timing,

-

21.

Demonstrates appropriate non-verbal behavior,

-

22.

If reads, writes doesn’t interfere with dialogue/rapport,

-

23.

Is not judgmental,

-

24.

Empathizes with and supports patient,

-

25.

Appears confident

Closing the session

-

26.

Encourages patient to discuss any additional points,

-

27.

Closes interview by summarizing briefly,

-

28.

Contracts with patient re: next steps

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harasym, P.H., Woloschuk, W. & Cunning, L. Undesired variance due to examiner stringency/leniency effect in communication skill scores assessed in OSCEs. Adv in Health Sci Educ 13, 617–632 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9068-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-007-9068-0