Abstract

This study analyses the experienced age discrimination of old European citizens and the factors related to this discrimination. Differences in experienced discrimination between old citizens of different European countries are explored. Data from the 2008 ESS survey are used. Old age is defined as being 62 years or older. The survey data come from 28 European countries and 14,364 old-age citizens. Their average age is 72 years. Factor analysis is used to construct the core variable ‘experienced discrimination’. The influence of the independent variables on experienced discrimination is analysed using linear regression analysis. About one-quarter of old European citizens sometimes or frequently experience discrimination because of their age. Gender, education, income and belonging to a minority are related to experienced age discrimination. Satisfaction with life and subjective health are strongly associated with experienced age discrimination, as is trust in other people and the seriousness of age discrimination in the country. Large, significant differences in experienced discrimination due to old age exist between European countries. A north-west versus south-east European gradient is found in experienced discrimination due to old age. The socio-cultural context is important in explaining experienced age discrimination in old European citizens. Old-age discrimination is experienced less frequently in countries with social security arrangements. Further research is needed to understand the variation in (old) age discrimination between European countries. Measures recommended include increasing public awareness about the value of ageing for communities and changing public attitudes towards the old in a positive way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of old people is growing rapidly in developed societies. In terms of health and social service policies ageing is seen as a potential problem for future services and a lack of resources (personnel in care and funds for state pensions). The ageing of the population will cause significant social changes as well, especially in regard to the financing of retirement schemes and the delivery and financing of care (OECD 2011). The OECD expects a decrease in informal care, because people having to work longer and female participation in the labour market are increasing.

The ageing of the population affects all aspects of society. This may therefore create negative attitudes and lead to discrimination against persons of advanced age: ‘Age discrimination is probably the least understood and least recognised of social prejudices and as such, potentially the most hazardous for a rapidly ageing society’ as stated by Midwinter (Wait and Midwinter 2005). A profound transformation in the meaning of old age was observed towards the end of the 20th century (Walker 1993). In the past century, family structures have undergone dramatic changes, and as a consequence so have the patterns of contact between older people with children and siblings. Often it was assumed—wrongly—that family contacts would decrease. This was not the case 50 years ago (Townsend 1963). More recently, the Danish Longitudinal (Panel) Future Study showed an increase in contact between parents with children and siblings and a more positive view of the family as a supportive institution in the 1980s and 1990s (Leeson 2005). At the same time, research indicates that around 15% of Europeans 60 years or older often feel lonely (Dijkstra 2009). A decade ago, European elderly reported that they received more respect than less, but in the last decade this trend has been reversing (van den Heuvel 2011, submitted). Elderly abuse has been a concern for a number of years and a subject of action in the EU. The existence of elderly abuse, especially the abuse of the most dependent old, has been well documented (Teaster and Anetzberger 2010).

With the increasing number of old citizens, policy concerns about the ageing population and the changes of the situation older people have to live in, the question arises: to what extent does age discrimination exist these days in Europe and do old people experience discrimination because of their age? Research shows an overwhelmingly negative attitude towards the elderly in the United States (Bishop et al. 2008), and European data also show that age is increasingly a reason for discrimination: between 2008 and 2009 a considerable increase of 16% was noticed (Eurobarometer 2009). Age is the most frequently mentioned reason for discrimination in EU member states.

In this article, we will analyse to what extent old people themselves experience discrimination because of their age in Europe and which factors are related to the extent of the experienced discrimination.

To do so, we first have to define what we mean by old age. Next, the concept of (age) discrimination will be presented followed by an overview of factors which are reported to be related to experienced discrimination because of old age.

Old age is not a well-defined concept. When a person is old or considered to be old varies over time, between individuals, civilisations and between categories of people and countries. It is often related to life expectancy and social care arrangements. In Europe, for statistical reasons and partly related to retirement schemes, the age of 65 years is labelled as ‘old age’. In this study, we use data from the European Social Study 2008 (ESS Round 4 2008) to define ‘old age’. People of ‘old age’ are people 62 years and over (see “Methods” section).

Discrimination is the outcome of a complex process in which a person, a group or a category of people are differentiated on specific beliefs and/or (often one) characteristics, whilst differentiation based on such beliefs and/or characteristics is seen societally as unjustified (Wait and Midwinter 2005). The way discrimination is exposed may be direct, i.e. explicitly and openly directed to persons with the characteristics, or indirect. In the latter case an action, regulation or behaviour seems neutral, but it has an adverse impact on persons with the given characteristics, or it seems positive but has negative outcomes in practice (Drury 1993; Roberts 2002; Macnicol 2006).

Displays of discrimination may be measured directly, i.e. observing and/or questioning the (extent of) discriminating actions and behaviours or indirectly, i.e. analysing the consequences of specific actions, measures or behaviours on their adverse effects. Statistical data and institutional measures may show age discrimination indirectly. Verbal antagonism, avoidance, physical aggression, extermination are measures for direct discrimination.

Discrimination because of age is seen as one of the most complex forms of discrimination (Cuddy et al. 2005; Macnicol 2006). Age itself is meaningless. It acquires meaning in social constructs (beliefs, attitudes and behaviour) as do race, gender etc. However, age itself is again stratified in specific constructs (roles with specific rights, rewards and responsibilities) and their own set of ‘age appropriate’ norms and behaviours. The same person may become an object of discrimination, when (s)he moves into another role because of age.

Age discrimination refers to all differentiations based on age as a proxy for roles related to specific age categories (Macnicol 2006). ‘Ageism’ is sometimes seen as special form of age discrimination. As formulated by Robert Butler, ageism is a combination of three connected elements: prejudicial attitudes towards older persons, discriminatory practices against older people and institutional practices and policies that perpetuate stereotypes about older people (Butler 1980; Wilkinson and Ferraro 2002). These three elements are amongst of the ways discrimination may be exposed, as explained above. Ageism indicates age discrimination. Some authors consider ageism as broader than age discrimination, referring to deeply rooted negative beliefs about old people and the ageing process (Clarke 2009). The special attention given towards the ageing of societies and the problems associated with it (affordability of welfare arrangements) may have led to special interest or behaviours in discrimination against people of old age. Therefore, as Williams (2009) argues, the term ‘ageism’ may have worked as an eye-opener, but it has to be understood within the discrimination framework.

In this study, we focus on direct age discrimination against old persons, i.e. do they experience negative expressions (words, behaviour) from fellow citizens because of their ‘old age’, i.e. 62 years and older?

Research on the relationships between experienced discrimination in old age and related factors is rare. Most research findings deal with attitudes and beliefs of younger citizens towards older citizens and with attitudes towards older workers and the institutional (labour market, wage structure) conditions of older workers versus younger ones. Many of these studies are executed in a laboratory context, where the effect of age is maximised and the impact of other factors is almost excluded (Morgeson et al. 2008). Recently, research on age discrimination in health care has been increasing, focusing on inequities in diagnostics and treatment of the old (Wait and Midwinter 2005; Adding life to years 2001; Clarke 2009). Still, even here research on experienced age discrimination is scarce, though opinions, including amongst health care professionals, are that age discrimination exists structurally in health care (Age Concern 2008; Williams 2009; Clarke 2009).

The discriminatory behaviour of citizens varies. On one hand, it may be related to personal characteristics (Bishop et al. 2008). On the other hand, social-economic circumstances, attitudes and beliefs (in local communities or states) and socio-legal norms in societies may play an important role (Vernon 1999). Three categories of factors are derived from the literature. The (extent of) experienced discrimination because of old age may be related to individual characteristics of the old persons, but also to attitudes and beliefs about discrimination in general and towards old people in communities and countries particularly. Individual characteristics include socio-demographic, health and well-being and other social and personal factors. Attitudes and beliefs may be embedded more widely in a social-cultural context, i.e. accepted norms and customs, regulations, social care arrangements, labour market and laws.

Generally, age, gender and socioeconomic status have been found to be correlated to various forms of discrimination, including age discrimination. In most studies, age groups consist of young versus old or the whole range of ages. Ethnicity has also been found to be associated with age discrimination (Bytheway et al. 2007). Various studies suggest that age discrimination occurs in cases of poor health and dependency (Pascoe and Richman 2009; Clarke 2009). The explanation for this relationship may flow in two directions. On one hand, old persons with poor health are discriminated against because of their dependency, need for care and the costs involved. On the other hand, being discriminated may lead to harmful health effects. Either way, experienced age discrimination will be related with poor health status. The same will be the case with well-being.

Jang et al. (2008) found an association between perceived discrimination amongst 45–74 years old and well-being, explaining that discrimination is an ‘unpleasant experience’ and reduces well-being. As in the case of health, the other way around is also possible.

The relationship between experienced discrimination and health status and well-being has been reported to be moderated by other individual factors such as coping style, sense of control and social support (Jang et al. 2008; Pascoe and Richman 2009).

Based on the literature, we will include the following individual factors in this study: age, gender, education, income, ethnicity, social support, subjective health and life satisfaction.

In general, there is only a weak link between what people generally think about ageing and how they behave towards old individuals (Vernon 1999). Neighbourhood characteristics are associated with perceived racial discrimination (Daily et al. 2010). The socio-cultural context of communities and countries may be related more or less to experienced age discrimination. Therefore, in this study, we will analyse the differences in experienced age discrimination of old people between European states.

A great deal of research is done on the relationship between attitudes and the tendency to discriminate. Less is known about the role of attitudes and beliefs and perceived discrimination. One study reported a strong association between the opinion that discrimination occurs frequently and experiencing discrimination (Salentin 2007). More generally, persons who feel safe and trust in other people may perceive discrimination less. In a study in four Central-Eastern European countries it was found that trust in fellow citizens is related to citizens’ norms (Coffé and van der Lippe 2010). In our study, we will include the opinion of older citizens on the extent of discrimination and trust in people as factors which might be associated with experienced age discrimination. Beliefs and customs are often internalised as stereotypes of a specific culture which result in implicit discrimination (Mossakowski 2003; Adams et al. 2006). Most studies embed attitudes and beliefs in a socio-cultural context. Therefore, we will take ‘opinion on the extent of discrimination’ and ‘trust in other people’ as indicators of the socio-cultural context people live in.

The objectives of this study are to analyse to what extent old persons in Europe experience discrimination because of their age. We will describe which individual and socio-cultural factors are related to this experienced discrimination. Differences in experienced discrimination between old citizens of European countries will also be explored.

Methods

Database

The data used in this study are derived from the European Social Survey (ESS Round 4 2008). Data file edition 3.0, which contains data from 28 countries, was used. ESS is an academically driven multi-country survey which has been administered in over 30 countries. Its three aims are:

-

to monitor and interpret changing public attitudes and values within Europe and to investigate how they interact with Europe’s changing institutions,

-

to advance and consolidate improved methods of cross-national survey measurement in Europe and beyond,

-

to develop a series of European social indicators, including attitudinal indicators.

ESS is funded via the European Commission’s 6th Framework Programme, the European Science Foundation and national funding bodies in each country.

The design is a cross-sectional study with random probability sampling amongst all persons aged 15 and over living in private households, regardless of their nationality, citizenship, language or legal status. The minimum target is a response rate of 70%. Data are collected in an hour-long face-to-face interview.

Old age

In the ESS 2008, European citizens were asked what age they considered people start to be described as ‘old’. Most respondents mentioned a specific age. The variation between age groups was small: young (15–39) people mention on average 60.7 years, middle aged (40–64) people 63.3 and the old (65 and over) 63.8. Based on these data, we used the average of 62 years as the criterium for ‘old age’.

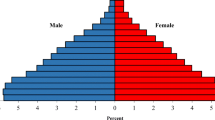

Population characteristics

For our study objective we selected people in the ESS 2008 study aged 62 years and over, meaning a total of 14,364 respondents. The average age was 72.0 years (SD 7.1); 58.5% were women, 41.5% men.

Education was measured on a 7-point scale (1 = did not complete primary school (9%) to 6 = university (17%) and 7 = beyond university (0.6%). The average education level was 2.5 (SD 1.5).

Most respondents were born in the country they currently live in; 6.6% were not. Most of those not born in the country they live in now came to the country they live in long ago (87% more than 20 years ago). In addition, respondents were asked whether they belonged to a minority group in the country: 5.3% said yes.

Experienced discrimination

In most studies, experienced or perceived discrimination is assessed by asking for the frequency of a specific disrespect or maltreatment (Salentin 2007; Jang et al. 2008). In ESS 2008, a few questions are about disrespect and maltreatment in relation to age. The following indicators are used to assess experienced discrimination:

-

How often were you treated with prejudice because of your age during last year?

-

How often did you feel a lack of respect because of your age last year?

-

How often were you treated badly because of your age last year?

By analysing the answers of European citizens aged 62 years or older to these questions, we measure the extent of experienced discrimination amongst old European citizens. Besides the face validity of these questions for measuring discrimination, the validity will be tested by analysing the relationship between the three questions.

Each question could be scored on a five point scale from never to very often. Based on the principal component analysis, factor scores for each respondent were calculated to be used in the regression analysis. In addition, the answers to each of the three questions were added and recoded into four categories. This is presented in Table 2 and in the country comparison (average score) instead of the factor scores.

Independent variables

Based on findings in the literature, we ordered the independent variables according to individual factors and socio-cultural context (including beliefs and attitudes). The following variables were selected for analysis, based on the literature (see before) and within the bounds of the data set.

Individual factors included are age, gender, level of education, household net income, ethnicity, satisfaction with life and subjective health. Measures of gender, age, level of education and household net income are standard measures by ESS. Ethnicity was measured using two indicators: born in country and belonging to a minority group. Subjective health is measured with the question ‘How do you rate your health?’ and Satisfaction with life is addressed with the question ‘How satisfied are you with life as a whole?’

Three indicators (‘How often do you socially meet with friends, relatives or colleagues?’ ‘Anyone to discuss intimate and personal matters with?’ and ‘How often do you take part in social activities compared to other with same age?’) were used to measure the social contacts/support of the respondent. However, the relationship between the indicators was low, as was Cronbach’s alpha. As a result, a single reliable measure could not be constructed. Therefore, we did not include social contacts/support in the analysis.

To measure socio-cultural context, we looked for various indicators in the ESS study. One item refers to the seriousness of age discrimination in the country. We used this as an indicator of the sensitivity to discrimination. Three indicators were used to measure the trust the respondents have in other people (‘Most people can be trusted vs. you cannot be too careful’; ‘Most people try to take advantage of you vs. try to be fair’; ‘Most of the time people are helpful vs. are mostly looking out for themselves’). Factor analysis showed one strong factor, measuring trust in others; the explained variance was 70% and factor loadings were over 0.82. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78. Factor scores were calculated on the basis of the principal component analysis.

In addition, we intended to use three questions as indicators for the social-cultural context people are living in: ‘Feeling of safety of walking alone in local area in the dark?’, ‘How often do you worry about your home being burgled?’ and ‘How often do you worry about becoming a victim of violent crime?’ Factor analysis showed one factor, but Cronbach’s alpha was too low to consider it as a reliable measure. Therefore, we did not include this variable in the analysis.

In addition, we used ‘country’ as another indicator for socio-cultural context. We will describe the differences in experienced discrimination between countries separately.

To analyse the influence of the independent variables on experienced discrimination, linear regression analysis was used. We used step-wise analysis to show the effect of the different set of variables on experienced age discrimination. The regression outcomes were checked for collinearity. Design weight and person weight were included in the analysis.

Results

Extent of experienced discrimination because of old age

The three indicators of experienced discrimination in old age are significantly correlated (the Pearson correlation varies from 0.64 to 0.78). Principal component analysis resulted in one overall factor showing experienced discrimination because of age (see Table 1). The explained variance is 79%; Cronbach’s alpha is 0.87.

The answers to the three questions of respondents aged 62 years or older are combined to present a more condensed overview (see Table 2). Discrimination was frequently experienced by 11% of European citizens aged 62 years or older in 2008. Frequently, means that respondents scored at least ‘very often’ on one of the items. The majority (52%) of older Europeans never felt discriminated against in 2008.

Individual and socio-cultural factors related to experienced discrimination

Step-wise linear regression analysis was used to analyse the association between experienced discrimination because of age and individual and socio-cultural factors. First, socio-demographic variables, satisfaction with life and subjective health were entered, followed by trust in people and seriousness of age discrimination.

The final model of the linear regression results are presented in Table 3. The beta coefficients are high for satisfaction with life, good subjective health, seriousness of age discrimination and trust in people. The total explained variance is 13%. Individual factors contribute 11%.

From amongst the socio-demographic variables, gender, level of education and household income contributed significantly also in the first and second step to explain experienced discrimination. In the first step, age has a significance level between 0.05 and 0.10, but this disappeared when trust in people and seriousness of age discrimination were introduced. Born in the country does not contribute, but belonging to a minority group does.

Women aged 62 years or older reported more experienced age discrimination than men, whilst persons with a high level of education reported less experienced age discrimination, as did persons with high household income and not belonging to a minority group.

Older persons who are satisfied with their lives and who experience good subjective health reported less discrimination because of age.

Persons who express trust in their fellow citizens reported less experienced age discrimination. If people state that age discrimination is very serious in their country, they themselves also experience discrimination because of age more often. The latter two contributed 2% towards explaining experienced discrimination because of age.

Experienced old-age discrimination in 28 European countries

The last part of the analysis describes the variation between European countries in experienced discrimination because of old age. Factor scores are calculated for each respondent based on the three indicators for age discrimination. The average factor scores per country varied from −0.433 (Sweden), indicating low experienced discrimination because of age amongst Swedish older citizens, to 0.542 (Czech Republic) indicating high experienced discrimination because of old age in Czech old citizens.

Large and significant differences exist between European countries in experienced discrimination of the elderly based on age. In 17 countries, older citizens indicate that they do not frequently experience discrimination because of old age. Old citizens in Sweden, Denmark and Norway experience the least discrimination because of age, followed by the Netherlands, Switzerland, Portugal, Croatia and Slovenia. In eight countries older citizens report being discriminated against because of age more frequently.

Experienced discrimination is high in Czech Republic, Russian Federation, Ukraine and Romania, followed by Slovakia, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey.

As shown in Table 2 the scores of the three indicators were added and recoded into four categories (1 = never; 4 = frequent) of experienced discrimination by old citizens because of their age. The total average score for experienced discrimination in the 28 European countries was 1.83 (SD 1.03). The average score per country is presented in Graph 1. Differences between countries are statistically significant (Gamma 0.180 p < 0.000).

Five countries (Czech Republic, Russia, Ukraine, Romania and Slovakia) have an average score above 2.0. Four countries (Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Portugal) have a score below 1.5.

As previously mentioned, 11% of old European citizens reported having frequently experienced discrimination because of their age (see Table 2). The proportion of old people who do so in each country is presented in Fig. 2. Older citizens of Czech Republic (23%), Ukraine (20%), Russia (18%) and Romania (16%) report experiencing age discrimination most frequently, followed by Turkey (14%), Israel (12%), Bulgaria (11%) and Slovakia (11%).

The least frequently experienced age discrimination was reported by citizens of Sweden (2%), Denmark (2%), Norway (3%), Switzerland (3%), the Netherlands (4%), Croatia (4%) and Slovenia (4%) (see Graph 2).

Discussion

The existence of discrimination because of old age may not be a surprising ‘phenomenon’. Thirty-five years ago R. Butler wrote, “We have shaped a society which is extremely harsh to live in when one is old. The tragedy of old age is not the fact that each of us must grow old and die but that the process of doing so has been made unnecessarily and at times excruciatingly painful, humiliating, debilitating and isolating through insensitivity, ignorance and poverty.” (Butler 1975) Various studies in the 1990s indicated the danger of enduring discrimination because of old age in Europe. This study presents new, recent data about actual discrimination because of old age as experienced by old citizens themselves in 28 European countries. Over one out of ten old European citizen experiences discrimination because of their age.

The proportion of people aged 62 years or older being discriminated against in Europe is worrying, even more so given the large differences between European countries or ‘regions’. Old citizens in East and South-East European countries report more frequently experienced discrimination. There are other data, which suggest that discrimination in general is more ‘accepted’ in these countries (Marsh and Sahin-Ditmen 2002; http://www.age-platform.eu/en/age-policy-work/anti-discrimination). However, it seems that discrimination based on age is increasing, whilst 20 years ago the main reason for discrimination was ethnicity. Such a trend is also reported in other studies (Eurobarometer 2010). Whether this trend is related to the growing concern about the ageing of society and its consequences for the affordability of the current retirement system and long-term care facilities needs further research. Other data show that (non-old) European citizens seriously worry about the affordability of retirement and long-term care arrangements in the future (van den Heuvel 2011). Intergenerational solidarity may be at stake here. Anyway, discrimination because of old age is a serious matter. Having said that this should not be derived from the strong association between experienced discrimination and ‘seriousness of age discrimination’ as was found in the regression analysis in this study. This finding might in fact be seen as a tautology. Those old citizens who experience discrimination because of their old age indeed will recognize it as a serious matter. But it is not a tautology per se. We compared the average score of all citizens per country on the question ‘how serious is discrimination in your country because of age’, using this as an indicator of the sensitivity to age discrimination generally, with the average score of experienced discrimination per country by old citizens. Spearman’s nonparametric correlation is 0.462 (p = 0.048), meaning that in countries where discrimination because of age is seen as a serious problem by all citizens old people experienced more discrimination. Discrimination because of old age is a serious matter in civilized societies.

Generally, the socio-demographic characteristics of the old have a modest relationship with age discrimination. The regression analysis has shown that income and education of old people do contribute modestly to explain discrimination experienced by them. Upon comparing 28 European countries, a north-west versus east-south gradient of experienced old-age discrimination by old people is shown by the data. Given the relation with income and education, one might expect average income and average education level per country to be related to experienced discrimination by old citizens. Such a relation could support the north-west versus the south-east gradient. The highest average net household income was found in Belgium, Norway and Sweden, the lowest in Czech Republic, Turkey and Ukraine. Comparing the average scores on income and education level of all citizens per country and the average experienced discrimination score of the old citizens, a statistically significant relation was found between the average of total net household income per country as reported by all citizens and average experienced discrimination by old citizens (Spearman −0.484, p = 0.014). Such an association was not found for average education per country.

Subjective health and satisfaction with life are more strongly related to experiencing discrimination. As was mentioned in the introduction, this relationship may be explained by the effect of discrimination on well-being and health status, but it may also work the other way around. People who are not satisfied by life or who experience weak health may become more easily excluded.

How should we understand this north-west versus east-south gradient? A study in Eastern Europe indicated that older people are less happy with life because of the consequences of the transitions since 1989, and that they rated their health more often as poor (Knurowski et al. 2004). This is the case more often in women than in men. However, variations in norms and ideas about citizenship also show considerably variance in Central-Eastern European countries (Coffé and van der Lippe 2010). This underlines the importance looking at the socio-cultural context.

The social-cultural context—only indirectly indicated in this analysis—might be an important concept for explaining this variation in experienced discrimination in old age (Tesch-Römer and Kondratowitz 2006). We found a strong association between experienced age discrimination and ‘trust in other people’. Citizenships norms, including concern for fellow citizens, vary across Europe and even within ‘south-eastern’ European countries (Coffé and van der Lippe 2010). Social involvement and participation differ between European countries and show up in social arrangements.

Social arrangements, like in ‘north-west’ (Scandinavian) countries, may be seen as indications of societal solidarity and acceptance of citizens’ norms, including persons with ‘other characteristics’ (minority, disability, frail old and sexual orientation). Citizens’ norms and their social arrangements ‘protect’ against age discrimination. In this study, we did could not construct reliable indicators for the social-cultural context, partly because the ESS study has others objectives. The idea behind north-west versus south-east gradient is that some social-cultural factors like belief in equal opportunities or preferences for traditions dominate in some countries and not in others. These dominating values might be related with tendency to discrimination. Using the variable ‘Important that people are treated equally and have equal opportunities’ as an indicator for equal opportunities, we found that in countries where more citizens agreed with this statement, old people on average reported less experienced discrimination (Spearman 0.545, p = 0.003). The average score of most countries is very positive (average 1.62 on a 5 point scale; 1 = agree strongly); most negative are the scores of citizens in Bulgaria and Czech Republic.

A negative association (Spearman −0.526, p = 0.004) was found between the average score of all citizens per country on the variable ‘Important to follow traditions and customs’ as indicator of ‘traditionalism’ and the average experienced discrimination per country by old citizens. Here, the average score of citizens of Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Poland and Turkey indicates a clear preference for tradition and customs, whilst citizens of Estonia, Finland, France and Sweden have opposite preferences. More preferences for traditions and customs at country level mean more average experienced discrimination by old citizens.

The importance of further studying the societal and cultural environment old people is living into understand discrimination towards the old may be evident based on these exploring analyses. Indeed, the importance was stated by Butler 35 years ago.

The ESS data offer a unique possibility for conducting comparative research. The methods of sampling, data collection and use of common instruments all guarantee high quality data. This is considered a strong point in comparative research, which also applies to this study (Tesch-Römer and Kondratowitz 2006). Of course, using secondary data—collected for other objectives—limits the inclusion of variables which may contribute to explain the reasons for age discrimination. Variables were measured for other purposes and combined in this analysis to present a conceptual variable (experienced age discrimination, trust, attitudes and beliefs etc.). This is a weakness in this study, implicitly due to the current exploratory state in the field of age discrimination.

Experienced discrimination because of old age is measured here with three self-reported questions. Observational methods and statistical data could add other ways of age discrimination. More theoretical and empirical research is needed in this field. It is important to execute further research to understand the causes and mechanism of old-age discrimination. Besides surveys and the opinions of experts (especially in health care and employment) concerning discrimination in old age, experimental and anthropological studies are needed to understand the underlying mechanism of old-age discrimination.

The policy implications of the results of this study could be significant. However, due to the cross-sectional design and secondary data and due to the descriptive and cross-sectional nature of the study, it is important to wait for further research data. Nevertheless, it is believed that a profound discussion of these modest outcomes could be helpful in exploring policy measures. One of these measures should include actions to increase public awareness and to change public attitudes (Giles et al. 2010). Attention might be especially given to intergenerational relationships, not only emphasising the differences but also the complementarity (Zaidi et al. 2010).

The question remains: how to ‘beat’ age discrimination? Research indicates that formulating ‘rights’ for the elderly is an insufficient base to fight ageism (Marsh and Sahin-Ditmen 2002; Giles et al. 2010). Many organisations, including those representing the elderly, put a great deal of effort into these activities (see http://www.soros.org/initiatives/justice/about). Having rights is no guarantee to being protected against discrimination, even when cases are brought to court. In the end, this may even be an inefficient way to protect old citizens against discrimination. Pensions, disability and social security have a stronger effect on the ‘norms of ageing’ than anti-discrimination legislation (Lahey 2010). Therefore, high priority should be given to research which will explain the mechanism behind old-age discrimination.

References

Adams A, Buckingham CD, Arber S, McKinlay JB, Marceau L, Link C (2006) The influence of patient’s age on clinical decision‐making about coronary heart disease in the USA and the UK. Ageing Soc 26:303–322

Adding life to years: report of the expert group on health care of older people (2001) National Health Service, Scotland

Age concern. Ageism in Britain. An age concern research briefing (2008) Policy Unit Age Concern, England

Bishop JL, Roden BK, Bolton AC, Wynn RV (2008) An assessment of the relationships among attitudes toward the elderly, death anxiety, and locus of control. Psychology Program, Department of Behavioral and Social Science, University of Montevallo, Montevallo, Presentation Dominican University of California

Butler R (1975) Why survive? Being old in America. Harper & Row, New York

Butler RN (1980) Ageism: a foreword. J Soc Issues 36:8–10

Bytheway B, Ward R, Holland C, Peace S (2007) Too old. Older people’s account of discrimination, exclusion and rejection. A report from the Research on Age Discrimination project (RoAD) to help the aged. Help the Aged, London

Clarke A (2009) Ageism and age discrimination in primary and community health care in the United Kingdom. Centre for Policy on Ageing

Coffé H, van der Lippe T (2010) Citizenship norms in Eastern Europe. Soc Indic Res 96:479–496

Cuddy AJC, Norton MI, Fiske ST (2005) The old stereotype: the pervasiveness and persistence of the elderly stereotype. J Soc Issues 61:265–283

Daily AB, Kasl SV, Holford TR, Lewis TT, Jones BA (2010) Neighborhood- and individual-level socioeconomic variation in perceptions of racial discrimination. Ethn Health 15:145–163

Dijkstra PA (2009) Older adults loneliness: myths and realities. Eur J Ageing 6:91–100

Drury E (1993) Age discrimination against older workers in the European Community. EC, Brussels

ESS Round 4: European Social Survey Round 4 Data (2008) Data file edition 3.0. Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Norway—Data Archive and distributor of ESS data

Eurobarometer 317 (2009) Discrimination in the EU in 2009. Special Eurobarometer Report 317. European Commission, Brussels

Eurobarometer 321 (2010) Poverty and social exclusion. Special Eurobarometer Report 321. European Commission, Brussels

Giles L, Brewer ET, Mosqueda L, Huba GJ, Melchior LA (2010) Vision for 2020. J Elder Abuse Negl 22:375–386

http://www.age-platform.eu/en/age-policy-work/anti-discrimination. Accessed 2 Dec 2010

Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Small BJ (2008) Perceived discrimination and psychological wellbeing: the mediating and moderating role of sense of control. Int J Ageing Hum Dev 66:213–227

Knurowski T, Lazic D, van Dijk JP, Geckova A, Tobiasz-Adamczyk B, van den Heuvek WJA (2004) Survey of health status and quality of life in Poland and Croatia. Croat Med J 45:750–756

Lahey JN (2010) International comparison of age discrimination laws. Res Ageing 32:679–697

Leeson GW (2005) Changing patterns of contact with and attitudes to the family in Denmark. J Intergener Relatsh 3:25–45

Macnicol J (2006) Age discrimination. An historical and contemporary analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Marsh A, Sahin-Ditmen M (2002) Discrimination in Europe. Report, Policy Studies Institute, London

Morgeson FP, Reider MH, Campion MA, Bull RA (2008) Review of research on age discrimination in the employment interview. J Buss Psychol 22:223–232

Mossakowski KN (2003) Coping with perceived discrimination: does ethnic identity protect mental health? J Health Soc Behav 44:318–331

OECD (2011) Help wanted? Providing and paying for long-term care. OECD report, Paris

Pascoe EA, Richman LS (2009) Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 135:531–554

Roberts, E (2002) Age discrimination in health care. In: Age discrimination in public policy: a review of evidence. Help the Aged, London

Salentin K (2007) Determinants of experience of discrimination in minorities in Germany. Int J Confl Violence 1:32–50

Teaster PB, Anetzberger GJ (2010) Elder abuse in contemporary society: programs, policy, and politics. J Elder Abuse Negl 22:3–5

Tesch-Römer C, Kondratowitz HJ (2006) Comparative ageing research: a flourishing field in need of theoretical cultivation. Eur J Ageing 3:155–167

Townsend P (1963) The family life of old people: an inquiry in East London. Penguin, Harmondsworth

van den Heuvel WJA (2011) Value reorientation and intergenerational conflicts in ageing societies (Submitted)

Vernon AE (1999) Designing for change: attitudes toward the elderly and intergenerational programming. Child Youth Serv 20:161–173

Wait S, Midwinter E (2005) Promoting age equality in health care. A report for the alliance for health and the future, London

Walker A (1993) Age and attitude. European Commission, Brussels

Wilkinson J, Ferraro K (2002) Thirty years of ageism research. In: Nelson T (ed) Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge

Williams PW (2009) Age discrimination in the delivery of health care services to our elders. Faculty Publications Paper 79, Marquette University Law School

Zaidi A, Gasior K, Sidorenko A (2010) Intergenerational solidarity: policy challenges and societal responses. Policy Brief, European Centre Vienna

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: D. J. H. Deeg

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Heuvel, W.J.A., van Santvoort, M.M. Experienced discrimination amongst European old citizens. Eur J Ageing 8, 291–299 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0206-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0206-4