Abstract

The QALY is a useful outcome measure in cost-effectiveness analysis. But in determining the overall value of and societal willingness to pay for health technologies, gains in quality of life and length of life are prima facie separate criteria that need not be put together in a single concept. A focus on costs per QALY can also be counterproductive. One reason is that the QALY does not capture well the value of interventions in patients with reduced potentials for health and thus different reference points. Another reason is a need to separate losses of length of life and losses of quality of life when it comes to judging the strength of moral claims on resources in patients of different ages. An alternative to the cost-per-QALY approach is outlined, consisting in the development of two bivariate value tables that may be used in combination to estimate maximum cost acceptance for given units of treatment—for instance a surgical procedure, or 1 year of medication—rather than for ‘obtaining one QALY.’ The approach is a follow-up of earlier work on ‘cost value analysis.’ It draws on work in the QALY field insofar as it uses health state values established in that field. But it does not use these values to weight life years and thus avoids devaluing gained life years in people with chronic illness or disability. Real tables of the kind proposed could be developed in deliberative processes among policy makers and serve as guidance for decision makers involved in health technology assessment and appraisal.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ottersen, T., Førde, R., Kakad, M., Kjellevold, A., Melberg, H.O., Moen, A., Ringard, Å., Norheim, O.F.: A new proposal for priority setting in Norway: open and fair. Health Policy 120, 246–251 (2016)

The Swedish Parliamentary Priorities Commission: Priorities in Health Care. SOU 1995:5. Stockholm: The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs (1995)

Van de Wetering, E.J., Stolk, E.A., van Exel, N.J.A., Brouwer, W.B.F.: Balancing equity and efficiency in the Dutch basic benefits package using the principle of proportional shortfall. Eur. J. Health Econ. 14, 107–115 (2013)

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE): Appraising life-extending, end-of-life treatments. Guidelines. London: NICE (2009)

Menzel, P.: Strong Medicine. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1990)

Richardson, J.: Economic assessment of health care: theory and practice. The Australian Economic Review (1991). (1st quarter, 4–19)

Nord, E.: An alternative to QALYs: the saved young life equivalent (SAVE). Br. Med. J. 305, 875–877 (1992)

Williams, A.: Intergenerational equity: an exploration of the ‘fair innings’ argument. Health Econ. 6, 117–132 (1997)

Nord, E., Pinto, J.L., Richardson, J., Menzel, P., Ubel, P.: Incorporating concerns for fairness in economic evaluation of health programs. Health Econ. 8, 25–39 (1999)

Baltussen, R., Niessen, L.: Priority setting of health interventions: the need for multi-criteria decision analysis. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 4, 14 (2006)

Caro, J., Nord, E., Siebert, U., McGuire, A., McGregor, M., Henry, D., de Pouvourville, G., Atella, V., Kolominsky-Rabas, P.: The efficiency frontier approach to economic evaluation of health care interventions. Health Econ. 19, 1117–1127 (2010)

Norheim, O.F., Baltussen, R., Johri, M., Chisholm, D., Nord, E., Brock, D., et al.: Guidance on priority setting in health care (GPS-health): the inclusion of equity criteria not captured by CEA. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 12, 18 (2014)

Schlander, M., Garattini, S., Holm, S., Kolominsky-Rabas, P., Nord, E., Persson, U., et al.: Incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year gained? The need for alternative methods to evaluate medical interventions for ultra-rare disorders. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 3, 399–422 (2014)

World Health Organization: Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Final report of the WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: WHO (2014)

Hausman, D.: Valuing health. Oxford Press, New York (2016)

Nord, E.: The trade-off between severity of illness and treatment effect in cost-value analysis of health care. Health Policy 24, 227–238 (1993)

Nord, E.: Cost-value analysis of health interventions: introduction and update on methods and preference data. Pharmacoeconomics 33, 89–95 (2015)

Brock, D.: Justice and the ADA: does prioritizing and rationing health care discriminate against the disabled? Soc. Philos. Policy 12(2), 159–185 (1995)

Chombart de Lauwe, P.H.: Sociologie des aspirations. Denoël, Paris (1979)

Nord, E., Enge, A., Gundersen, V.: QALYs: is the value of treatment proportional to the size of the health gain? Health Econ. 19, 596–607 (2010)

Daniels, N.: Just health care. Cambridge University Press, New York (1985)

Oliver, A., Mossialos, E.: Evidence based public health policy and practice equity of access to health care: outlining the foundations for action. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 58, 655–658 (2004)

Nord, E.: Public values for health states versus societal valuations of health improvements: a critique of Dan Hausman’s ‘Valuing health’. Public Health Ethics (2016). doi:10.1093/phe/phw008

Stolk, E., Pickee, S., Ament, A., Busschbach, J.: Equity in health care prioritization: an empirical inquiry into social value. Health Econ. 74, 343–355 (2005)

Norwegian Ministry of Health.: White Paper on Priority Setting. Oslo (2016)

Harris, J.: The value of life. Routledge, London (1985)

Nord, E., Johansen, R.: Concerns for severity in priority setting in health care: a review of trade-off data in preference studies and implications for societal willingness to pay for a QALY. Health Policy 116, 281–288 (2014)

Richardson, J., Sinha, K., Iezzi, A., Maxwell, A.: Maximising health versus sharing: measuring preferences for the allocation of the health budget. Soc. Sci. Med. 75, 1351–1361 (2012)

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Jaime Caro, Paul Menzel, Jeff Richardson, and Michael Schlander for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

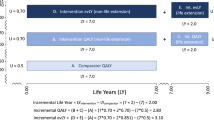

The following are five examples of the difference it may make to use the approach above rather than a conventional QALY approach.

Example 1: equal value of life

Assume two groups of patients with age 65 and health status 0.8 and 0.5, respectively. New treatments A and B can increase their health status to 0.9 and 0.6, respectively and their remaining life expectancy from 2 to 12 years. This amounts to the following QALY gains:

By contrast, willingness to pay is as follows according to Tables 1 and 2 and the correction for proportional gain in life expectancy:

So while A is valued almost 50% more than B in terms of QALYs, willingness to pay according to Tables 1 and 2 is much the same for both. The reasons are (1) that severity is accounted for and (2) that gained life years are not devalued for shortfall of health (i.e., not quality adjusted).

Example 2: diminishing marginal value of health improvements

Assume two groups of patients with health status 0.6. New treatments A and B can raise their health status by 0.3 and 0.1, respectively. If value is measured in QALYs, B justifies only a third of the cost that A justifies (0.1/0.3). If Table 1 applies, B justifies 44% (3600/8100). A stronger degree of evening out may be possible, see the “Discussion” section.

Example 3: diminishing marginal value of life years

Assume two diseases that typically occur around the age of 65 and reduce remaining life expectancy to 5 years. Proportional shortfall is then around 10/15 = 67%. New treatments A and B increase life expectancy by 10 and 5 years, respectively. Disregarding reduced health in the gained years, and applying a 3% annual discount rate to future years, the QALY gains are 7.3 for A and 4.0 for B. By contrast, using Table 2 and the correction for proportional gain, the willingness to pay would be as follows:

Thus, with QALYs discounted at 3% the value of A is 82% higher than the value of B, while with Table 2 the willingness to pay is only 46% higher for A than for B.

Example 4: age and gains in length of life

As noted earlier, the Norwegian Ministry of Health has proposed that willingness to pay for a QALY gained by a new technology should increase with the absolute shortfall of QALYs, given current treatment. No exact gradient is indicated, but given background documents and current practice in the Norwegian Medicine Agency, one may envisage something like a linear gradient from 10,000 euros for a QALY when the absolute shortfall is 1 QALY to 90,000 euros for a QALY when the absolute shortfall is 20 QALYs or more (Norwegian Ministry of Health 2016). This translates into an increase in the WTP per QALY of 4200 euros for each increase of 1 QALY in absolute shortfall.

Assume two diseases with typical onset around age 30 and 65, respectively. Both lead to death within a year’s time. Given other health losses that normally occur anyway, the absolute shortfall is around 40 QALYs for those who get the first disease (the young), and 10 QALYs for those who get the second disease (the elderly). New medicines A and B provide an additional life year in both patient groups.

With QALYs and grading by absolute shortfall at the rate indicated above, the willingness to pay for A and B will be 90,000 and 48,000 (10,000 + 4200 × 9) euros. Table 2 suggests 90,000 and 50,000. It thus captures the intention of the Ministry to favour the young when it comes to providing additional life years (the fair innings argument in the original, narrow sense).

Example 5: age and improvements in quality of life

By contrast, assume two diseases with typical onset around the age of 30 and 70, respectively that both reduce health status to 0.6, but do not affect length of life. Given other health losses that occur anyway, absolute shortfall is around 15 QALYs for those who get the first disease (young people), and 3 QALYs for those who get the second disease (elderly people). New medicines A and B raise health status by 0.2 in both patient groups.

With QALYs and grading by absolute shortfall at the rate described above, the willingness to pay for each year of medication (yielding 0.2 QALY) will be as follows:

In the alternative approach, willingness to pay per year of medication would be 6300 euros in both cases (Table 1). Unlike what follows from weighting willingness to pay by absolute shortfall, the alternative approach implies equal willingness pay for technologies for the young and the elderly when it comes to improving quality of life.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nord, E. Beyond QALYs: Multi-criteria based estimation of maximum willingness to pay for health technologies. Eur J Health Econ 19, 267–275 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-017-0882-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-017-0882-x

Keywords

- QALY

- Societal value

- Graded willingness to pay

- Proportional shortfall

- Absolute shortfall

- Cost value analysis