Abstract

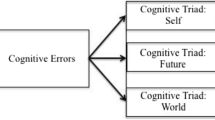

Research on depression showed patterns of maladaptive thinking reflecting themes of negative self-evaluation, a pessimistic view on the world and hopelessness regarding the future, the so-called cognitive triad. However, it is still unclear if these cognitive aspects are also a clear marker of depressive symptoms in children. Therefore in the current study we will investigate to what extent the cognitive triad contributes to the prediction of depressive symptoms. Four hundred and seventy-one youngsters with a mean age of 12.41 years, of which 53 % were male, participated in this study. They filled in self-report questionnaires to measure depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, emotional and behavioral problem behavior and the cognitive triad. The cognitive triad explained 43.5 % of the variance in depressive symptoms as reported by the children themselves without controlling for comorbid psychopathology. When controlling for comorbid anxiety and externalizing behavior problems, adding the cognitive triad contributes to depressive symptoms with 11 % on top of the 45 % explained variance by comorbid problems. The findings were observed both in the child (10–12 years) and adolescent (13–15 years) subsample. The standardized betas for the view on the World were low and did only reach the significance level in the adolescent sample. The cognitive triad represents a key component of depressive symptoms, also in younger age groups. Specifically the negative view on the Self and the negative view on the Future is already associated with depressive symptoms in both the child and adolescent subsample. The common variance among different psychopathologies (depression, anxiety and behavioral problems) still needs to be sorted out clearly.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Beck AT et al (1979) Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press, New York

Hankin BL et al (2008) Beck’s cognitive theory of depression in adolescence: specific prediction of depressive symptoms and reciprocal influences in a multi-wave prospective study. Int J Cogn Therapy 1(4):313–332

Laurent J, Stark KD (1993) Testing the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis with anxious and depressed youngsters. J Abnorm Psychol 102(2):226–237

Kaslow NJ et al (1992) Cognitive triad inventory for children—development and relation to depression and anxiety. J Clin Child Psychol 21(4):339–347

Beck AT (1976) Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New American Library, New York

Beck R, Perkins TS (2001) Cognitive content-specificity for anxiety and depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Therapy Res 25(6):651–663

Lamberton A, Oei TPS (2008) A test of the cognitive content specificity hypothesis in depression and anxiety. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 39(1):23–31

Calvete E et al (2005) Self-talk and affective problems in college students: valence of thinking and cognitive content specificity. Span J Psychol 8(1):56–67

Cho YR, Telch MJ (2005) Testing the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis of social anxiety and depression: an application of structural equation modeling. Cogn Therapy Res 29(4):399–416

Ohrt T, Sjodin I, Thorell LH (1999) Cognitive distortions in panic disorder and major depression: specificity for depressed mood. Nord J Psychiatry 53(6):459–464

Safren SA et al (2000) Differentiating anxious and depressive self-statements: combined factor structure of the anxious self-statements questionnaire and the automatic thoughts questionnaire-revised. Cogn Therapy Res 24(3):327–344

Dozois DJA, Frewen PA (2006) Specificity of cognitive structure in depression and social phobia: a comparison of interpersonal and achievement content. J Affect Disord 90(2–3):101–109

Epkins CC (1996) Cognitive specificity and affective confounding in social anxiety and dysphoria in children. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 18(1):83–101

Jolly JB (1993) A multimethod test of the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis in young adolescents. J Anxiety Disord 7(3):223–233

Jacobs L, Joseph S (1997) Cognitive triad inventory and its association with symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents. Personal Individ Differ 22(5):769–770

Lodge J, Harte DK, Tripp G (1998) Children’s self-talk under conditions of mild anxiety. J Anxiety Disord 12(2):153–176

Ronan KR, Kendall PC (1997) Self-talk in distressed youth: states-of-mind and content specificity. J Clin Child Psychol 26(4):330–337

Treadwell KRH, Kendall PC (1996) Self-talk in youth with anxiety disorders: states of mind, content specificity, and treatment outcome. J Consult Clin Psychol 64(5):941–950

Miranda R, Fontes M, Marroquin B (2008) Cognitive content-specificity in future expectancies: role of hopelessness and intolerance of uncertainty in depression and GAD symptoms. Behav Res Ther 46(10):1151–1159

Miranda R, Mennin DS (2007) Depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and certainty in pessimistic predictions about the future. Cogn Therapy Res 31(1):71–82

Wong SS (2008) The relations of cognitive triad, dysfunctional attitudes, automatic thoughts, and irrational beliefs with test anxiety. Current Psychol 27(3):177–191

Smith PN, Mumma GH (2008) A multi-wave web-based evaluation of cognitive content specificity for depression, anxiety, and anger. Cogn Therapy Res 32(1):50–65

Dalgleish T et al (1997) Information processing in clinically depressed and anxious children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(5):535–541

Muris P, van der Heiden S (2006) Anxiety, depression, and judgments about the probability of future negative and positive events in children. J Anxiety Disord 20(2):252–261

Jacobs RH et al (2008) Empirical evidence of cognitive vulnerability for depression among children and adolescents: a cognitive science and developmental perspective. Clin Psychol Rev 28(5):759–782

Ouimet AJ, Gawronski B, Dozois DJA (2009) Cognitive vulnerability to anxiety: a review and an integrative model. Clin Psychol Rev 29(6):459–470

Reid SC, Salmon K, Lovibond PF (2006) Cognitive biases in childhood anxiety, depression, and aggression: are they pervasive or specific? Cogn Therapy Res 30(5):531–549

Epkins CC (2000) Cognitive specificity in internalizing and externalizing problems in community and clinic-referred children. J Clin Child Psychol 29(2):199–208

Barriga AQ et al (2000) Cognitive distortion and problem behaviors in adolescents. Crim Justice Behav 27(1):36–56

Timbremont B, Braet C (2006) Brief report: a longitudinal investigation of the relation between a negative cognitive triad and depressive symptoms in youth. J Adolesc 29(3):453–458

Kovacs M (1992) Children’s depression inventory (CDI). Multi-Health Systems inc., New York

Timbremont B, Braet C (2002) Children’s depression inventory: Nederlandstalige versie. Lisse, Swets & Zeitinger

Beck AT et al (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4(6):561

Craighead WE et al (1998) Factor analysis of the children’s depression inventory in a community sample. Psychol Assess 10(2):156–165

Timbremont B, Braet C, Dreessen L (2004) Assessing depression in youth: relation between the children’s depression inventory and a structured interview. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 33(1):149–157

Garcia LF, Aluja A, del Barrio V (2008) Testing the hierarchical structure of the children’s depression inventory: a multigroup analysis. Assessment 15(2):153–164

Molina CS, Gomez JR, Pastrana MCV (2009) Psychometric properties of the spanish-language child depression inventory with hispanic children who are secondary victims of domestic violence. Adolescence 44(173):133–148

Donnelly M, Wilson R (1994) The dimensions of depression in early adolescence. Pers Individ Differ 17(3):425–430

Chorpita BF et al (2000) Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale. Behav Res Ther 38:835–855

Muris P, Meesters C, Schouten E (2002) A brief questionnaire of DSM-IV-defined anxiety and depression symptoms among children. Clin Psychol Psychother 9(6):430–442

Spence SH (1997) Structure of anxiety symptoms among children: a confirmatory factor-analytic study. J Abnorm Psychol 106(2):280–297

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. University of Vermont, Reasearch Center for Children, Youth and Families, Burlington

Verhulst FC, Van der Ende J (2004) Handleiding voor de CBCL/6-18 en YSR (manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile and youth self report and profile). Sophia Children’s Hospital Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Rotterdam

Little R (1988) A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc 83:1198–1202

Schafer J (1997) Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Shapman and Hall, London

Hollingshead A (1975) Four factor index of social status. Yale University Press, New haven

Beesdo K et al (2007) Social anxiety disorder: patterns of incidence and secondary depression risk. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 17:S511–S512

Beck AT (1967) Depression: causes and treatment. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Graziano F, Bonino S, Cattelino E (2009) Links between maternal and paternal support, depressive feelings and social and academic self-efficacy in adolescence. Eur J Dev Psychol 6(2):241–257

Yildirim I (2007) Depression, test anxiety and social support among Turkish students preparing for the university entrance examination. Egitim Arastirmalari-Eurasian. J Edu Res 7(29):171–188

Lorant V et al (2003) Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 157(2):98–112

Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT (1987) Child adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull 101(2):213–232

Acknowledgments

The present study was funded by Ghent University and conducted in collaboration with students. No other funding was available. The study is part of larger projects on emotion regulation (phd projects of Wante, Vanbeveren and Theuwis). The data published here were presented on professional European conferences but not published elsewhere.

Conflict of interest

There is a conflict of interest as the author (Braet) made several authorized version of translated tests and she will receive royalties for this. The co-authors and I do not have any interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research, and ethical standards were followed in the conduct of the study. The local Ethical Committee of Ghent University has approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from both the children and their parents. No animals have been used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braet, C., Wante, L., Van Beveren, ML. et al. Is the cognitive triad a clear marker of depressive symptoms in youngsters?. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24, 1261–1268 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0674-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0674-8