Abstract

Despite accumulated experimental evidence of the negative effects of exposure to media-idealized images, the degree to which body image, and eating related disturbances are caused by media portrayals of gendered beauty ideals remains controversial. On the basis of the most up-to-date meta-analysis of experimental studies indicating that media-idealized images have the most harmful and substantial impact on vulnerable individuals regardless of gender (i.e., “internalizers” and “self-objectifiers”), the current longitudinal study examined the direct and mediated links posited in objectification theory among media-ideal internalization, self-objectification, shame and anxiety surrounding the body and appearance, dietary restraint, and binge eating. Data collected from 685 adolescents aged between 14 and 15 at baseline (47 % males), who were interviewed and completed standardized measures annually over a 3-year period, were analyzed using a structural equation modeling approach. Results indicated that media-ideal internalization predicted later thinking and scrutinizing of one’s body from an external observer’s standpoint (or self-objectification), which then predicted later negative emotional experiences related to one’s body and appearance. In turn, these negative emotional experiences predicted subsequent dietary restraint and binge eating, and each of these core features of eating disorders influenced each other. Differences in the strength of these associations across gender were not observed, and all indirect effects were significant. The study provides valuable information about how the cultural values embodied by gendered beauty ideals negatively influence adolescents’ feelings, thoughts and behaviors regarding their own body, and on the complex processes involved in disordered eating. Practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

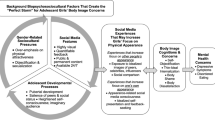

As shown in Fig. 1 each of the constructs was assessed at a different point in time. Specifically, media-ideal internalization, self-objectification, negative body-feelings (i.e., body shame and appearance anxiety), and disordered eating (i.e., dietary restraint, binge eating) were measured at wave 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. Each wave was separated by a 1-year interval during which the variables under investigation can develop or change [13, 33, 50–53]. This spacing of the assessments across four waves and the statistical control of prior (Time x -1) levels of each endogenous (dependent) variable would ensure temporal precedence of media-ideal internalization to self-objectification, of self-objectification to negative body-feelings, and of negative body-feelings to disordered eating [51]. However, in contrast to the other four endogenous (continuous) model variables (i.e., self-objectification, body shame, appearance anxiety, and dietary restraint), for binge eating we could not statistically control prior (Time x -1) relevant levels, as this variable was operationalized categorically (see measures for details) at wave 4 (Fig. 1) [51]. In line with prior longitudinal research [33, 50] we assessed therefore binge eating episodes in each wave, and subsequently participants who reported binge eating episodes at the first three waves were excluded from main analyses (see binge eating in measures section). This strategy would both ensure a more rigorous and a truly prospective test of our hypothesis and prevent over-estimation of model parameters [33, 50, 51, 53], as there is increasing evidence that binge eating (if present) tends to be relatively stable or increase during the developmental period that the current study covers, and adolescents who report binge eating relative to those who did not, showed significantly higher levels of body mass, media-ideal internalization, negative affect, depressed mood, restraint, and body image concerns [4, 14, 50, 53, 54].

Age- and sex-adjusted BMI centiles from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [56] were used to determine whether participants at baseline were underweight (less than 5th percentile), normal weight (5th percentile to less than 85th percentile), overweight (85th percentile to less than 95th percentile) and obese (equal to or greater than the 95th percentile). However, as BMI percentiles are poorly suited for structural equation modeling analyses [51] and not recommended as a (proxy) measure of change in adiposity in longitudinal studies of adolescents see [57], in our planned statistical analyses BMI was used as a continuous variable that was z-standardized with respect to gender and age according to the CDC standards [56]. This permitted us to include the full scale of weight (z-BMI) and reduce potential measurement error [33, 51].

As the present study was conducted as part of the Mind & Body Project [58]; see also acknowledgments available annual data regarding BMI and depression were used to provide an additionally conservative test of our hypotheses, as prior research suggests that both variables co-vary with ED and objectification theory constructs (Fig. 1) and their values differ over time (i.e., time-varying variables) [12, 32–34, 50, 52].

Although participants who reported binge eating at the month prior to the first three annual assessments (n = 36), relative to those who did not, showed significantly higher mean scores in all study variables, there were no significant differences in terms of demographics between these two groups. Given that some readers might wonder if the results from the model under investigation would have changed if the 36 participants had been included, the structural model (Fig. 1) was re-estimated including these participants. Because this had the effect of amplifying the range of all model variables, we noted the expected increases in structural parameter estimates (relative to the sample without these participants) (β|Δ| = 0.06–0.16, M|Δ| = 0.10, SD |Δ| = 0.03) and in the proportion of total variation of each endogenous variable (3.1–7.8 %) explained by the model. In line with prior research [33, 50] we reported the more conservative analysis without the inclusion of 36 cases to avoid over-estimation (even minor) of structural parameters and ensure that we conducted a truly prospective test of our hypothesis [51, 53]. Due to space considerations, the detailed results of the analyses briefly reported here are available from the corresponding author upon request.

To ensure that measures assessed at multiple time points (i.e., self-objectification via body surveillance, body shame, appearance anxiety, dietary restraint) were not allowed to change over time, the same items in the three parcels for these measures were included at initial (i.e., self-objectification via body surveillance at T1) and later (i.e., self-objectification via body surveillance at T2) time points [51, 73]. Also, to control for possible systematic error due to the repeated assessment, the measurement error amongst the identical observed indicators of the latent variables was allowed to be correlated over time [51, 73]. For instance, the measurement error for the 1st observed indicator of self-objectification via body surveillance from T1 was allowed to correlate with the measurement error for the same 1st observed indicator of self-objectification via body surveillance at T2. This was also done for the 2nd and 3rd observed indicators of self-objectification via body surveillance from T1 and T2. In the same manner, correlated error for the observed indicators of the other longitudinal latent variables (i.e., body shame, appearance anxiety, dietary restraint) were included.

As the current manuscript includes the maximum permitted number of tables and figures, the correlations among the 10 latent variables and the 28 observed indicators and time-varying covariates stratified by gender are available on request from the corresponding author.

Modification indices provided by Mplus were detected in both the measurement and structural model but their magnitude (<5.0) suggested that any not originally specified parameters did not impact the fit of model to the data [73].

References

Allen KL, Byrne SM, Oddy WH, Crosby RD (2013) DSM–IV–TR and DSM-5 eating disorders in adolescents: Prevalence, stability, and psychosocial correlates in a population-based sample of male and female adolescents. J Abnormal Psychol 122:720–732

Le Grange D, Lock J (2011) Eating disorders in children and adolescents. Guilford Press, New York

Keel PK (2010) Epidemiology and course of eating disorders. In: Agras WS (ed) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 25–32

Tanofsky-Kraff M (2008) Binge eating among children and adolescents. In: Jelalian E, Steele R (eds) Handbook of child and adolescent obesity, 1st edn. Springer, New York, pp 41–57

Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR (2011) Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:714–723

Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Wille N, Hölling H, Vloet TD, Ravens-Sieberer U, BELLA study group (2008) Disordered eating behaviour and attitudes, associated psychopathology and health-related quality of life: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17:82–91

Stice E, Marti C, Shaw HE, Jaconis M (2009) An 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescents. J Abnormal Psychol 118:587–597

Hay PJ, Claudino AM (2010) Evidence-based treatment for the eating disorders. In: Agras WS (ed) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 452–479

Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN (2007) A meta-analytic review of eating disorder prevention programs: encouraging findings. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 3:233–257

Stice E, Ng J, Shaw H (2010) Risk factors and prodromal eating pathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:518–525

Jacobi C, Fittig E (2010) Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. In: Agras WS (ed) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 123–136

Stice E (2002) Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 128:825–848

Stice E, Marti CN, Durant S (2011) Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behav Res Ther 49:622–627

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Larson NI, Eisenberg ME, Loth K (2011) Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Associ 111:1004–1011

Loth KA, MacLehose R, Bucchianeri M, Crow S, Neumark-Sztainer D (2014) Predictors of dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.016

Levine MP, Smolak L (2010) Cultural influences on body image and the eating disorders. In: Agras WS (ed) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 223–246

Dakanalis A, Riva G (2013) Mass media, body image and eating disturbances: the underlying mechanism through the lens of the objectification theory. In: Sams LB, Keels JA (eds) Body image: gender differences, sociocultural influences and health implications, 1st edn. Nova Science Publishers, New York, pp 217–236

Calogero RM, Thompson JK (2010) Gender and body image -Volume 2. In: Chrisler JC, McCreary DM (eds) Handbook of gender research in psychology, 1st edn. Springer, New York, pp 153–184

Benowitz-Fredericks CA, Garcia K, Massey M, Vasagar B, Borzekowski DL (2012) Body image, eating disorders, and the relationship to adolescent media use. Pediat Clin North Am 59:693–704

Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS (2008) The role of the media in body image concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol Bull 143:460–476

Bartlett CP, Vowels CL, Saucier DA (2008) Meta-analyses of the effects of media images on men’s body-image concerns. J Soc Clin Psychol 27:279–310

Keel PK, Klump LK (2003) Are eating disorders culture-bound syndromes? Implications for conceptualizing their etiology. Psychol Bull 129:747–769

Field A, Javaras KM, Aneja P, Kitos N, Camargo CA, Taylor CB, Laird NM (2008) Family, media, and peer predictors of becoming eating disordered. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 162:574–575

Ferguson CJ, Winegard B, Winegard BM (2011) Who is the fairest one of all? How evolution guides peer and media influences on female body dissatisfaction. Rev Gen Psychol 15:11–28

Vartanian LR, Hopkinson MM (2010) Social connectedness, conformity, and internalization of societal standards of attractiveness. Body Image 7:86–89

Hausenblas HA, Campbell A, Menzel JE, Doughty J, Levine M, Thompson JK (2013) Media effects of experimental presentation of the ideal physique on eating disorder symptoms: a meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Clin Psychol Rev 33:168–181

American Psychological Association, Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls (2010) Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report-full.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2014

Calogero RM, Tantleff-Dunn S, Thompson JK (2011) Self-objectification in women: causes, consequences, and counteractions. American Psychological Association, Washington

Fitzsimmons-Craft EE (2011) Social psychological theories of disordered eating in college women. Review and integration. Clini Psychol Rev 31:1224–1237

Dakanalis A, Di Mattei VE, Bagliacca EP, Prunas A, Sarno L, Riva G, Zanetti MA (2012) Disordered eating behaviors among Italian men: objectifying media and sexual orientation differences. Eat Disord 20(5):356–367

Morry MM, Staska SL (2001) Magazine exposure: Internalization, self-objectification, eating attitudes, and body satisfaction in male and female university students. Can J Behav Sci 4:269–279

Moradi B, Huang Y (2008) Objectification theory and psychology of women: a decade of advances and future directions. Psychol Women Quartert 32:377–398

Allen KL, Byrne SM, McLean NJ (2012) The dual-pathway and cognitive-behavioural models of binge eating: prospective evaluation and comparison. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21:51–62

Tiggemann M (2013) Objectification Theory: of relevance for eating disorder researchers and clinicians? Clinic Psychol 17:35–45

Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA (1997) Objectification theory: toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol Women Quartert 21:173–206

Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA, Noll SM, Quinn DM, Twenge JM (1998) That swimsuit becomes you: sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. J Pers Soc Psychol 75:269–284

Noll SM, Fredrickson BL (1998) A mediational model linking self-objectifcation, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychol Women Quartert 22:623–636

Moradi B (2010) Addressing gender and cultural diversity in body image: objectification theory as a framework for integrating theories and grounding research. Sex Roles 63:138–148

Tiggemann M, Kuring JK (2004) The role of objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. Brit J Clin Psychol 43:299–312

Daniel S, Bridges SK (2010) The drive for muscularity in men: media influences and objectification theory. Body Image 7:32–38

Calogero RM (2009) Objectification processes and disordered eating in British women and men. J Health Psychol 14:394–402

Riva G, Gaudio S, Dakanalis A (2014) The Neuropsychology of Self-Objectification. Eur Psychol. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000190

McKinley NM, Hyde JS (1996) The objectified body consciousness scale: development and validation. Psychol Women Quartert 20:181–215

McKinley NM (1998) Gender differences in body esteem: the mediating effect of objectified body consciousness and actual/ideal weight discrepancy. Sex Roles 39:113–123

Dakanalis A, Timko CA, Clerici M, Zanetti MA, Riva G (2014) Comprehensive examination of the trans-diagnostic cognitive behavioral model of eating disorders in males. Eat Behav 15(1):63–67

Fairburn CG (2008) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press, New York

Slater A, Tiggemann M (2002) A test of objectification theory in adolescent girls. Sex Roles 46:343–349

Harrison K, Fredrickson BL (2003) Women’s sport media, self-objectification and mental health in black and white adolescent females. J Commun 53:216–232

Slater A, Tiggemann M (2010) Body image and disordered eating in adolescent girls and boys: a test of objectification theory. Sex Roles 63:42–49

Dakanalis A, Timko CA, Carrà G, Clerici M, Zanetti MA, Riva G, Caccialanza R (2014) Testing the original and the extended dual-pathway model of lack of control over eating in adolescent girls. A two-year longitudinal study. Appetite 82:180–193. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2014.07.022

Little TD (2013) Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Press, New York

Grabe S, Hyde JS, Lindberg SM (2007) Body objectification and depression in adolescents: the role of gender, shame and rumination. Psychol Women Quartert 31:164–175

Stice E (2001) A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology. Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. J Abnormal Psychol 110:124–135

Goldschmidt AB, Wall MM, Loth KA, Bucchianeri MM, Neumark-Sztainer D (2014) The course of binge eating from adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychol 33(5):457–460. doi:10.1037/a0033508

Lazzeri G, Rossi S, Pammolli A, Pilato V, Pozzi T, Giacchi MV (2008) Underweight and overweight among children and adolescents in Tuscany (Italy). Prevalence and short-term trends. J Prev Med Hyg 49:13–21

Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL (2002) 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11:1–190

Must A, Anderson S (2006) Body mass index in children and adolescents: considerations for population-based applications. Int J Obesity 30:590–594

Dakanalis A (2014) Body image and Axis I Disorders: a series of validation, cross-sectional, and longitudinal studies on community and clinical sample: a series of validation studies on community and clinical samples. Dissertation, University of Pavia

Stefanile C, Matera C, Nerini A, Pisani E (2011) Validation of an Italian version of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (SATAQ-3) on adolescent girls. Body Image 8:432–436

Nerini A, Matera C, Pisani E, Stefanile C (2011) Validation of an Italian version of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 on boys. Counseling 6:235–244

Thompson JK, van den Berg P, Roehrig M, Guarda AS, Heinberg LJ (2004) The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. Int J Eat Disorder 35:293–304

Matera C, Nerini A, Stefanile C (2013) The role of peer influence on girls’ body dissatisfaction and dieting. Eur Rev Appl Psychol 63:67–74

Dakanalis A, Clerici M, Caslini M, Favagrossa L, Prunas A, Volpato C, Riva G, Zanetti MA (2014) Internalization of sociocultural standards of beauty and disordered eating behaviours: the role of body surveillance, shame and social anxiety. J Psychopathol 20(1):33–37

Hart TA, Flora DB, Palyo SA, Fresco DM, Holle C, Heimberg RG (2008) Development and examination of the Social Appearance Anxiety Scale. Assessment 15:48–59

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z (1993) The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (eds) Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment, 1st edn. Guilford Press, New York, pp 317–360

Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, Crow SJ (2012) Psychometric evaluation of the Eating Disorder Examination and the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 45:428–438

Mannucci E, Ricca V, Di Bernardo M, Rotella CM (1996) Eating disorders and eating disorder examination. Diabete 8:127–131

Faravelli C, Ravaldi C, Truglia E, Zucchi T, Cosci F, Ricca V (2006) Clinical epidemiology of eating disorders: results from the Sesto Fiorentino Study. Psychoth Psychosom 75:376–383

Goldstein TR, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Brent DA (2007) Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: a 1-year open trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:820–830

Conti L (1999) Repertorio delle scale di valutazione in psichiatria—Tomo II. Società Editrice Europea, Firenze

Chambers WJ, Puig-Antich J, Hirsch M, Paez P, Ambrosini PJ, Tabrizi MA, Davies M (1985) The assessment of affective disorders in children and adolescents by semi structured interview: test-retest reliability of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children, present episode version. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42:696–702

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998-2011) Mplus User’s Guide Sixth Edition. Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles

Byrne BM (2011) Structural equation modeling with Mplus: basic concepts. Application and Programming, Routledge

Russell DW, Kahn JH, Spoth R, Altmaier EM (1998) Analyzing data from experimental studies: a latent variable structural equation modeling approach. J Couns Psychol 45:18–29

Hu L, Bentler P (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6:1–55

Preacher KJ, Kelley K (2011) Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol Methods 16:93–115

Aubrey JS (2006) Effects of sexually objectifying media on self-objectification and body surveillance in undergraduates: results of a 2-year panel study. J Commun 56:366–386

Dakanalis A, Timko CA, Favagorssa L, Riva G, Zanetti MA, Clerici M (2014) Why do only a minority of men report severe levels of eating disorder symptomatology, when so many report substantial body dissatisfaction? Examination of exacerbating factors. Eat Disord. doi:10.1080/10640266.2014.898980

Hebl MR, King EB, Lin J (2004) The swimsuit becomes us all: ethnicity, gender, and vulnerability to self-objectification. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 30:1322–1331

Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK (2011) Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: a meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychol Bull 137:660–681

Stice E, Presnell K (2010) Dieting and the Eating Disorders. In: Agras WS (ed) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 148–179

Spoor STP, Stice E, Bekker MHJ, van Stien T, Croon MA, van Heck GL (2006) Relations between dietary restraint, depressive symptoms, and binge eating: a longitudinal study. Int J Eat Disord 39:700–707

Kroon Van Diest AM, Perez M (2013) Exploring the integration of thin-ideal internalization and self-objectification in the prevention of eating disorders. Body Image 10:16–25

Dakanalis A, Carrà G, Calogero R, Zanetti MA, Gaudio S, Caccialanza R, Riva G, Clerici M (2014) Testing the cognitive-behavioural maintenance models across DSM-5 bulimic-type eating disorder diagnostic groups: a multi-centre study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. doi:10.1007/s00406-014-0560-2

Dakanalis A, Carrà G, Clerici M, Riva G (2014) Efforts to make clearer the relationship between body dissatisfaction and binge eating. Eat Weight Disord. doi:10.1007/s40519-014-0152-1

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of the Mind and Body Project at the University of Pavia (which involves a series of independent studies aiming at validating numerous body image measures, and examining prospectively the associations among body image and full-blown AXIS I disorders among both clinical and community samples [58]) and supported by a grant from the Onassis Foundation (O/RG 12410). Special appreciation is expressed to all participants and their parents.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Ethical standards

Informed consent was obtained from both the youngsters and their parents. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pavia (ID No: 2228/009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dakanalis, A., Carrà, G., Calogero, R. et al. The developmental effects of media-ideal internalization and self-objectification processes on adolescents’ negative body-feelings, dietary restraint, and binge eating. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24, 997–1010 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0649-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0649-1