Abstract

Objective

The aim of this review was to provide a systematic overview including a quality assessment of studies about oral health and orofacial pain in older people with dementia, compared to older people without dementia.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library. The following search terms were used: dementia and oral health or stomatognathic disease. The quality assessment of the included articles was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Results

The search yielded 527 articles, of which 37 were included for the quality assessment and quantitative overview. The median NOS score of the included studies was 5, and the mean was 4.9 (SD 2.2). The heterogeneity between the studies was considered too large to perform a meta-analysis. An equivalent prevalence of orofacial pain, number of teeth present, decayed missing filled teeth index, edentulousness percentage, and denture use was found for both groups. However, the presence of caries and retained roots was higher in older people with dementia than in those without.

Conclusions

Older people with dementia have worse oral health, with more retained roots and coronal and root caries, when compared to older people without dementia. Little research focused on orofacial pain in older people with dementia.

Clinical relevance

The current state of oral health in older people with dementia could be improved with oral care education of caretakers and regular professional dental care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During recent decades, an improvement in oral health care was seen, and consequently, an increase in the number of remaining teeth at higher ages [1]. Aging is an important risk factor in the development of medical conditions [2], and general health has a wide-ranging interaction with oral health [3–12]. Therefore, with the aging of the population, an increase in oral health problems is to be expected.

Oral health in older people has been described in several studies, examining the number of teeth present, dentures, oral disease, and caries. Edentulousness is prevalent among older people all over the world and is highly associated with socio-economic status [1]. Dentures are particularly frequent among older people in the developed countries [4]. In these countries, full dentures in both the upper and lower jaw are worn by one third to half of the older population, while partial dentures or full dentures in one jaw are worn by three quarters of the older population [3]. Dental caries is highly prevalent in older people in several countries, such as Australia and the USA [5, 6] and is closely associated with social and behavioral factors [3, 6, 7]. More specifically, caries tends to be more prevalent in people with low income, irregular dentist visits, lower frequency of brushing teeth, and high sugar consumption [7–9]. The caries increments of older people (between 0.8 and 1.2 newly affected tooth surfaces per year) exceed that of adolescents (between 0.4 and 1.2 newly affected tooth surfaces per year) [6]. Altogether, older people have more oral health problems than younger adults, and also orofacial pain is considered to increase with age in the general population [10].

Oral health problems become even more prevalent in older people with dementia; as the disorder progresses, cognition, motor skills, and self-care decline, increasing the risk of oral health problems [11, 12]. Even though an increasing interest in oral health in older people with dementia is seen in recent years, an up-to-date review of literature, comparing oral health in older people with and without dementia, is lacking. Furthermore, a review of orofacial pain in older people with dementia is lacking entirely, while oral health problems can be an important cause of orofacial pain and discomfort. Consequently, the aim of this review was to provide a systematic overview including a quality assessment of studies about the oral health and orofacial pain of older people with dementia, compared to older people without dementia. For this review, the focus was on health of dental hard tissues and orofacial pain, representing the following available data: percentages of people with orofacial pain, edentulousness and dentures, the Decayed Missing Filled Index, number of teeth present and retained roots, and number of teeth with coronal and root caries. The health of oral soft tissues will be reviewed in a separate article.

Methods

Search, study selection, and quality assessment

A literature search was performed on March 31, 2016 in the following electronic databases: PubMed, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library. In PubMed, the following search query was used: ((((“Oral Health”[Mesh] OR “Oral Health” [tiab])) OR (“Stomatognathic Diseases”[Mesh])) AND ((“Dementia”[Mesh] OR “Dementia”[tiab])). In CINAHL and the Cochrane Library, the same search terms were used, with database queries adjusted to the specific database. No restrictions with regard to language, year of publication, or methodology were applied during the search in order to maximize the inclusion of appropriate articles. Articles published in languages other than Dutch, English, and German were assessed by native speakers with dental knowledge for that particular language. Next, the titles, abstracts, and full texts were reviewed according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: older people with dementia, oral health, stomatognathic disease, facial pain, and useable data. Exclusion criteria were as follows: age below 60, no dementia, not about oral health or stomatognathic disease, case report, review, and no useable data (e.g., no quantitative data).

The screening of the titles, abstracts, and full texts, as well as the assessment of the quality of the Dutch, English, and German studies, was done independently by a dentist (SD) and a neuropsychologist (TB). The criteria were formulated in advance, and disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. Articles published in other languages were screened and assessed by a native speaker (for the particular language) with a background in dentistry. The reference lists of the included articles were scanned for complementary studies. If full texts were not available, or the dementia diagnosis or oral health data was unclear, the original authors were contacted up to a maximum of three times. If the dementia diagnosis or oral health data remained unclear, the article was excluded. The quality of the remaining articles, including risk of bias, was assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), using a maximum score of 9 [13]. In this review, a NOS quality score of 7 (=78 % of the maximum score) or more, was considered a high score.

Data extraction

Although the search focused on oral health in general, this review only discusses the dental hard tissue variables. The oral soft tissue variables will be reported in a separate review. The division between dental hard and soft tissues is often seen in articles that report oral health in older people with dementia [5, 14–16]. The first review author (SD) extracted the data from the included studies, and the second (TB) and last author (FL) checked the extracted data. The following data were extracted from the included articles: (1) study design (e.g., cross-sectional, case-control, cohort study); (2) participant characteristics (including age, dementia diagnosis, subtype, and severity); and (3) outcome measures, including orofacial pain, dentures, edentulousness, number of teeth present [17], decayed missing filled teeth (DMFT) index [18], coronal caries, root caries, and retained roots. If a study published baseline and follow-up data within the same article, only the baseline data was used. The principal summary measures used were percentages and means, including standard deviation. The heterogeneity of the data was checked.

Results

Study selection, characteristics, and participants

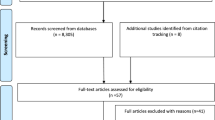

The search yielded 577 studies, up to publication year 2016. After the duplicates had been removed, 527 studies remained. The titles and abstracts of the remaining studies were screened, leading to the exclusion of 428 studies because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The 99 remaining full text articles were then examined for eligibility, of which 62 were then excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Only one study was added through scanning the reference lists of the included articles [19]. Thereafter, the quality of the 37 included studies was assessed. The flowchart of search is presented in Fig. 1. During the review process, 11 authors were contacted for further information of which seven replied. Additional information about the dementia diagnosis was given by Chen et al. and Del Brutto et al. [20–23] and additional data was provided by authors of Bomfim et al., Fjeld et al., Kersten et al., Lee et al., and Stewart et al. [24–27].

Of the final 37 included studies (Table 1), 11 were cohort studies, 6 were case-control studies, 19 were cross-sectional studies, and 1 had an randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. Most of the studies were in English; the articles of Nishiyama et al. and Sumi et al. were in Japanese [50, 55]. The relevant information of these two Japanese studies was extracted by a native Japanese speaker with dental knowledge; the study of Nishiyama et al. was excluded for not involving older people with dementia.

Altogether, the included studies about dental hard tissues involved 3770 participants with dementia and 4036 participants without dementia. The mean age of the participants with dementia was 78.18, and the mean age of the participants without dementia was 74.0 years. The reported method to classify the group of people with dementia varied. Seven studies specified the dementia subtype: Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and other types of dementia, such as Lewy bodies [30, 35, 36, 38, 42, 51, 52]. Three studies divided the group according to dementia severity [26, 28, 41]. Four studies were about nursing home residents (Table 2), without separate data about older people with and without dementia [29, 56–58]. The authors of these studies (Chalmers et al. and Hopcraft et al.) were contacted, but it was impossible to obtain separate data for the participants with and without dementia.

Group and outcome variables

Dementia was classified (Table 1) with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III or IV) [60, 61] or International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) [62]; National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) [63, 64]; computed tomography (CT); Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI); Positron Emission Tomography (PET) [65]; Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [66]; classification of dementia by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW) of Japan [46]; and/ or the existing medical chart of the participant. In addition to dementia diagnosis, measurements for cognitive status were used, such as the Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT) [28, 67], Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [68], or Minimum Data Set Cognitive Score (MDS-COGS) [33, 69]. Additionally, functional measures (e.g., Activities of Daily Living) were used.

The studies showed a variety of outcome measures concerning dental hard tissues (Table 1). The most used measures were number of teeth present [17], DMFT index [70–72], number of retained roots, and number of teeth with coronal and root caries. The development of dental caries was measured using the following outcome measures: crude caries increment (CCI) [18, 36], root caries index (RCI) [3], net caries increment (NCI) [18, 36], and adjusted caries and filling increments (ADJCI) [18, 36]. The use of prosthetics was reported by percentages of edentulousness and presence of removable prosthetics.

Quality assessment

An overview of the results of the quality assessment with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [13] is presented in Tables 3, 4, 5, and 6. The NOS scores of the assessed articles ranged from 1 to 9; the median score was 5 and the mean was 4.9 (SD 2.2). Of the 37 studies, 9 studies had an NOS score of 7 or higher.

In 14 (=53.8 %) of the non-cohort the studies, the DSM, ICD, or NINCDS-ADRDA was used for the classification of the dementia diagnosis. For 30 (=81.1 %) studies, the participants demonstrated good representativeness of the classification “older people with dementia.” Controls, in this case older people without dementia, often (=54.1 %) came from other sources than the cases. In only 11 (=29.7 %) of the non-cohort studies, it was explicitly stated that the controls had no history of dementia. Of all 37 studies, 51.4 % had comparable age and 37.8 % had comparable gender between cases and controls. Almost all studies (=91.9 %) used a standardized, structured method for the dental examination. Only 3 studies (=18.2 % of the non-cohort studies) described the non-response rate [25, 45, 52]. For most of the 11 cohort studies (=90.9 %), the follow-up period was longer than 3 months. At the same time, the number of subjects lost to follow-up was reported in only two (=22.2 %) of the cohort studies.

Results for each outcome variable

With respect to edentulousness, a wide range of percentages between studies was seen among older people with and without dementia (Table 7). For people without dementia, percentages varied from 14.0 to 70.0 % [28, 32] and for older people with dementia from 11.6 to 72.7 % [51, 49].

In terms of denture utilization, there was also a great variation among older people with and without dementia (Table 8). For older people without dementia, percentages ranged from 17.0 to 81.8 % [47, 73]; for older people with dementia, this number ranged from 5.0 to 100.0 % [42, 47]. The lowest percentage (5.0 %) was seen in a group of people with severe dementia (MMSE score below 10) [47].

The number of teeth present was the most commonly used indicator for dental health, and there was a wide range within both groups (Table 9). For people without dementia, it varied between 2.0 and 20.2 [24, 37], and for people with dementia, it varied between 1.7 and 20.0 [51, 49].

The DMFT index (Table 10) was 19.7 to 26.1 in people without dementia [5, 42], and 14.9 to 28.0 [48, 49] in people with dementia. The lowest DMFT was 14.9, which was derived from a cross-sectional study from Thailand examining older people with dementia without using a control group [49]. Only five studies compared older people with and without dementia, and just one study found a significant difference between the two groups; DMFT 25.5 in people without and DMFT 28.0 in people with dementia [48].

Taking the DMFT categories separately, “decay” varied from 0.0 to 2.9 in the group of older people without dementia [14, 15, 58] and 0.3 to 6.0 in the group of older people with dementia [15, 31], “missing” from 9.3 to 28.2 in the group without dementia [28, 45] and 10.2 to 27.3 in the group with dementia [26, 28], and “filled” from 0.7 to 25.7 in the group without dementia [14, 28] and 0.8 to 23.9 in the group with dementia [14, 49].

The reviewed studies showed that older people with dementia had more coronal caries (0.1–2.9) [35, 38, 52] than older people without dementia (0.0–1.0) [14, 15, 35, 38]. In addition, older people with dementia had more root caries (0.6–4.9) [35, 38, 52] than people without dementia (0.3–1.7) [14, 15, 35, 38]. Furthermore, retained roots were more common in people with dementia (0.2–10) [14, 35] than in people without dementia (0.0–1.2) [5, 35]. (Table 11).

Although dental hard tissues can be an important source of orofacial pain, only seven of the included studies published data about the presence of orofacial pain [15, 19, 28, 33, 34, 44, 74]. The presence of reported dental pain in older people with dementia varied between 7.4 and 21.7 %. Only in the study of Cohen-Mansfield and Lipson, pain with dental etiology was the central research question [33]. In this study, 60.0 % of the assessed participants were considered to have a dental pain-causing condition (Table 12). For older people without dementia, the orofacial pain prevalence was 6.7–18.5 % [28, 34].

The heterogeneity, specifically the clinical and methodological variability, between the studies was considered too large to perform a meta-analysis.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review with a quantitative overview of oral health variables in older people with dementia, compared to older people without dementia. Several qualitative reviews already stated the importance of good oral health in older people with dementia [75–83]. This review summarizes that the number of teeth present is comparable between older people with dementia and cognitively intact older people [14, 15, 25, 39, 43, 51, 52, 58]. The number of teeth present was the most commonly used measure for dental health, presumably because of its simplicity.

Studies that compare older people with and without dementia, showed similar, high DMFT scores for both groups [5, 32, 42, 48, 58]. Although the DMFT index gives an indication of the dental caries history as a whole, it does not distinguish between decayed, missing, and filled teeth separately. To get a better indication of disease and treatment need, the presence of caries should be assessed individually. Dental decay can be divided in coronal and root caries, which is a valuable distinction, considering the etiology and treatment methods of these types of caries. Coronal caries and root caries are significantly more common in older people with dementia than in those without dementia. This difference can be explained by cognitive, medical, and functional changes in people with dementia. For example, agitated behavior, characteristic for dementia, may complicate oral care [84], resulting in increased plaque accumulation and higher risk of caries [14]. In addition, reduced cooperation with dental treatment may constrain the possibilities of dental treatment [85]. The risk of caries increases even further, as a result of decreased submandibular saliva flow rates in people with Alzheimer’s disease [86], and changes in food composition (e.g., more sticky, grinded, and cariogenic food), which are often seen in people with dementia [39, 58]. Furthermore, functional changes in dementia, like declined handgrip and motor skills, play a role in the caries risk [39, 48]. More specifically, the decline in motor coordination might result in more difficulty performing oral care [48] and lower chewing and swallowing efficiency [39]. Remarkably, studies looking at coronal and root caries separately show significantly more caries in older people with dementia. One explanation is that some studies did not include root caries as decay in the DMFT index, as this was not mentioned in all articles [28, 42, 48, 87].

Retained roots are more present in older people with dementia than older people without dementia. This may be a result of the higher caries prevalence, fewer dental checks, resistance-to-care behavior, and decreased verbal communication skills [88, 89]. Lee and colleagues stated that, in the USA, people with dementia are less likely to visit the dentist regularly and the last visit to the dentist was a longer time ago, compared to older people without cognitive impairment [88]. Furthermore, an article about the barriers to good oral hygiene in nursing homes pointed out that resistance-to-care behavior is a major threshold in providing good oral care, which can be overcome by education of health workers and more time to provide oral care [90]. Additionally, verbal communication about dental problems and pain can be complicated in people with dementia, because of the short-term memory loss and language disturbances, like aphasia [91].

For edentulousness, the wide range in percentages might have been related to cultural differences [92, 93] and the small number of studies and participants. For instance, people in different countries have different diets, oral hygiene habits, and access to professional dental care [3, 94].

Dentures were worn by approximately the same percentage of older people either with or without dementia [12, 15, 51]. However, one study examined people in different stages of dementia and found lower percentages of denture use in people with more severe dementia [15, 47]. Adam and Preston suggest that “the high rate of not wearing dentures in the moderate/severe dementia group may in part be due to the dementia itself” [28]. A decrease of denture use with the progress of dementia could be explained by the lower tolerance of dentures, decreased control of oral musculature, decreased quality and quantity of saliva, and/ or higher risk of denture loss [85, 95]. Additionally, as people are edentulous for a longer time, the processus alveolaris resorbs more, resulting in a decrease of denture retention, especially in the lower jaw [96]. This increases the risk of aspiration of the lower dentures, particularly in older people with dementia, who are at increased risk of aspiration of foreign material [97].

Strikingly, orofacial pain in older people with dementia (7.4–21.7 %) was rarely studied [15, 33]. This is interesting, because this particular group seems to be at higher risk for this type of pain, considering the higher prevalence of oral health problems and the loss of verbal communication skills as the dementia progresses. Even more so, because being free of pain is considered an important factor in quality of life [1].

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this review are its systematic approach, the quality assessment of the articles, the quantitative overview of the dementia and oral health variables, and the involvement of a multidisciplinary team, including a neuropsychologist, dentists, and a pain specialist. For the search, there were no language limitations. Next to the described search, additional searches were done with the search terms facial pain, dental pain, DMFT, caries, and teeth present, in combination with dementia, to check the completeness of the results of the original search. Regarding the quality of the studies, most have a good, representative selection of cases and controls, a good comparability between the groups, and a systematic approach of the dental examination.

Limitations of this review are that the included studies showed a variety in outcome measures, not all included studies reported the standard deviations of the published mean values, and some studies about nursing home residents did not distinguish between older people with and without dementia. In addition, the number of RCTs was small, the number of high quality studies was low, and the heterogeneity was too large to perform a meta-analysis. Within the studies, the non-response and follow-up rate of the participants was often insufficiently described. In order to enable a better interpretation, it is important that these results are published. Despite the mentioned limitations, in this review the outcome measures, standard deviations and means, classification of dementia, and NOS scores of the studies are represented in a systematic manner to enhance a better interpretation of the different studies.

When looking at the effect of the quality on the studies, the main thing that strikes is the higher amount of coronal and root caries in older people without dementia in high quality studies [52], compared to all studies. Furthermore, the amount of retained roots in older people with dementia is the highest in the only high-quality study that compares retained roots in older people with and without dementia [35]. When only the high-quality studies are considered, the percentage of orofacial pain in older people with dementia is higher [15]. The ranges of outcome values get smaller when solely looking at the higher quality studies, especially for edentulousness [51, 52], denture use [47, 51], and the number of teeth present [37, 51, 52]. This seems logical, considering the smaller amount of studies involved.

Considerations and suggestions

This study shows a broad range of methods to classify the group of people with dementia. The MMSE is most commonly used, even though it is only a short cognitive screening instrument and not suitable for dementia diagnosis [98]. The advantages of the MMSE are its easy and quick application and the possibility of using this tool in moderate stages of dementia (from MMSE 14), where more extensive neuropsychological testing is no longer possible [68]. To diagnose dementia, extensive diagnostic examination should take place, and structural classification with systems like the ICD and DSM are preferred [61, 99, 100]. To distinguish between dementia subtypes, neuroimaging is a valuable addition [101].

For oral health, a broad range of methods is also seen, with the number of teeth present being the most common variable studied. While the number of teeth present is easy to measure and compare between studies, it does not specify the state of the teeth. The DMFT also provides information about the presence of caries and fillings in the teeth and is a widely used method, which enables comparing results between studies [102]. However, the method was developed in 1930 for epidemiological research in children [103] and seems unsuitable for present-day dentistry in people, which includes implants, crowns, and bridges. Further limitations of the DMFT are that teeth can be lost for reasons other than caries; it cannot be used to assess root caries; and it gives equal weight to decayed, missing, and filled teeth [104]. There is a need for an international, standardized method for dental examination in (older) people, dealing with the limitations stated above. Suggested items for the examination of dental hard tissues are the number of teeth present and the presence of implants, crowns, bridges, fillings, coronal caries, root caries, and retained roots. To investigate the chewing efficiency, Elsig and colleagues also suggested to include a chewing efficiency test into a standard examination [39]. In addition, the soft tissues should be examined. Suggestions for the examination of the dental soft tissues are beyond the scope of this article and will be discussed in a separate review.

With regard to oral health in older people with dementia, Chalmers and colleagues already suggested to examine the possible relationship between dental problems, dental pain, and challenging behavior in older people with dementia [14]. As of yet, this relationship is still scarcely studied, although dental discomfort might be an underlying cause of behavioral problems [105, 106]. This issue may even be more urgent for people with vascular dementia, in whom the pain experience is suggested to be increased, due to the presence of white matter lesions [107, 108]. However, the prevalence of orofacial pain in dementia subtypes has not been studied yet and is a suggested subject for future research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review found that older people with dementia have worse overall oral health than older people without dementia, including coronal caries, root caries, and retained roots. In contrast, they had an equivalent number of teeth present, similar rate of edentulousness, and equivalent decayed missing filled teeth index. Unfortunately, few studies have focused on orofacial pain in older people with dementia. Oral health, and specifically orofacial pain in older people with dementia, is in dire need of further attention.

References

Petersen PE (2003) The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century—the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 31:3–24. doi:10.1046/j.2003.com122.x

Rodríguez-Rodero S, Fernández-Morera JL, Menéndez-Torre E, et al. (2011) Aging genetics and aging. Aging Dis 2:186–195

Petersen PE, Yamamoto T (2005) Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 33:81–92. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00219.x

Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Bratthall D, Ogawa H (2005) Oral health information systems—towards measuring progress in oral health promotion and disease prevention. Bull World Health Organ 83:686–693

Bauer JG (2001) The index of ADOH: concept of measuring oral self-care functioning in the elderly. Spec Care Dentist 21:63–67

Leal SC, Bittar J, Portugal A, et al. (2010) Medication in elderly people: its influence on salivary pattern, signs and symptoms of dry mouth. Gerodontology 27:129–133. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2009.00293.x

Sloane PD, Ivey J, Helton M, et al. (2008) Nutritional issues in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 9:476–485. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2008.03.005

van der Maarel-Wierink CD, Vanobbergen JNO, Bronkhorst EM, et al. (2013) Oral health care and aspiration pneumonia in frail older people: a systematic literature review. Gerodontology 30:3–9. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00637.x

Thornhill MH, Dayer M, Lockhart PB, et al. (2016) Guidelines on prophylaxis to prevent infective endocarditis. Br Dent J 220:51–56. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.49

Moodley A, Wood NH, Shangase SL (2013) The relationship between periodontitis and diabetes: a brief review. SADJ 68(260):262–264

Jeftha A, Holmes H (2013) Periodontitis and cardiovascular disease. SADJ 68(60):62–63

Noble JM, Scarmeas N, Papapanou PN (2013) Poor oral health as a chronic, potentially modifiable dementia risk factor: review of the literature. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 13:384. doi:10.1007/s11910-013-0384-x

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Petersen J, Welch V, Losos M TP The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. In: Dep. Epidemiol. Community Med. Univ. Ottawa. New-castle Ottawa Scale (NOS), Canada. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Chalmers JM, Carter KD, Spencer AJ (2002) Caries incidence and increments in community-living older adults with and without dementia. Gerodontology 19:80–94. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2002.00080.x

Chalmers JM, Carter KD, Spencer AJ (2003) Oral diseases and conditions in community-living older adults with and without dementia. Spec Care Dent 23:7–17. doi:10.1111/j.1754-4505.2003.tb00283.x

Philip P, Rogers C, Kruger E, Tennant M (2012) Oral hygiene care status of elderly with dementia and in residential aged care facilities. Gerodontology 29:e306–e311. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00472.x

Yoshino K, Watanabe H, Fukai K, et al. (2011) Number of occlusal units estimated from number of present teeth. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 52:155–158. doi:10.2209/tdcpublication.52.155

Broadbent JM, Thomson WM (2005) For debate: problems with the DMF index pertinent to dental caries data analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 33:400–409. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00259.x

Rolim Tde S, Fabri GMC, Nitrini R, et al. (2014) Evaluation of patients with Alzheimer’s disease before and after dental treatment. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 72:919–924. doi:10.1590/0004-282X20140140

Chen X, Shuman SK, Hodges JS, et al. (2010) Patterns of tooth loss in older adults with and without dementia: a retrospective study based on a Minnesota cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:2300–2307. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03192.x

Chen X, Clark JJ, Chen H, Naorungroj S (2015) Cognitive impairment, oral self-care function and dental caries severity in community-dwelling older adults. Gerodontology 32:53–61. doi:10.1111/ger.12061

Chen X, Clark JJJ, Naorungroj S (2013) Oral health in nursing home residents with different cognitive statuses. Gerodontology 30:49–60. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00644.x

Del Brutto OH, Gardener H, Del Brutto VJ, et al. (2014) Edentulism associates with worse cognitive performance in community-dwelling elders in rural Ecuador: results of the Atahualpa project. J Community Health 39:1097–1100. doi:10.1007/s10900-014-9857-3

Bomfim FMS, Chiari BM, Roque FP (2013) Fatores associados a sinais sugestivos de disfagia orofaríngea em idosas institucionalizadas. CoDAS 25:154–163. doi:10.1590/S2317-17822013000200011

Fjeld KG, Mowe M, Eide H, Willumsen T (2014) Effect of electric toothbrush on residents’ oral hygiene: a randomized clinical trial in nursing homes. Eur J Oral Sci 122:142–148. doi:10.1111/eos.12113

Lee KH, Wu B, Plassman BL (2013) Cognitive function and oral health-related quality of life in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 61:1602–1607. doi:10.1111/jgs.12402

Stewart R, Stenman U, Hakeberg M, et al. (2015) Associations between oral health and risk of dementia in a 37-year follow-up study: the prospective population study of women in Gothenburg. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:100–105. doi:10.1111/jgs.13194

Adam H, Preston AJ (2006) The oral health of individuals with dementia in nursing homes. Gerodontology 23:99–105. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2006.00118.x

Chalmers J, Hodge C, Fuss J, et al. (2002) The prevalence and experience of oral diseases in Adelaide nursing home residents. Aust Dent J 47:123–130. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2002.tb00315.x

Chapman PJ, Shaw RM (1991) Normative dental treatment needs of Alzheimer patients. Aust Dent J 36:141–144. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.1991.tb01343.x

Chen X, Clark JJJ, Naorungroj S (2013) Oral health in older adults with dementia living in different environments: a propensity analysis. Spec Care Dent 33:239–247. doi:10.1111/scd.12006

Chu CH, Ng A, Chau AMH, Lo ECM (2015) Oral health status of elderly Chinese with dementia in Hong Kong. Oral Health Prev Dent 13:51–57. doi:10.3290/j.ohpd.a32343

Cohen-Mansfield J, Lipson S (2002) The underdetection of pain of dental etiology in persons with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 17:249–253. doi:10.1177/153331750201700404

de Souza RT, Fabri GMC, Nitrini R, et al. (2014) Oral infections and orofacial pain in Alzheimer’s disease: a case-control study. J Alzheimers Dis 38:823–829. doi:10.3233/JAD-131283

Ellefsen B, Holm-Pedersen P, Morse DE, et al. (2008) Caries prevalence in older persons with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:59–67. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01495.x

Ellefsen B, Holm-Pedersen P, Morse DE, et al. (2009) Assessing caries increments in elderly patients with and without dementia: a one-year follow-up study. JADA 140:1392–1400. doi:10.1002/pbc.24544

Ellefsen B, Holm-Pedersen P, Morse DE, et al. (2009) Assessing caries increments in elderly patients with and without dementia: a one-year follow-up study. J Am Dent Assoc 140:1392–1400

Ellefsen BS, Morse DE, Waldemar G, Holm-Pedersen P (2012) Indicators for root caries in Danish persons with recently diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. Gerodontology 29:194–202. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00560.x

Elsig F, Schimmel M, Duvernay E, et al. (2015) Tooth loss, chewing efficiency and cognitive impairment in geriatric patients. Gerodontology 32:149–156. doi:10.1111/ger.12079

Eshkoor SA, Hamid TA, Nudin SSH, Mun CY (2014) Association between dentures and the rate of falls in dementia. Med Devices (Auckl) 7:225–30. doi:10.2147/MDER.S63220

Furuta M, Komiya-Nonaka M, Akifusa S, et al. (2013) Interrelationship of oral health status, swallowing function, nutritional status, and cognitive ability with activities of daily living in Japanese elderly people receiving home care services due to physical disabilities. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 41:173–181. doi:10.1111/cdoe.12000

Hatipoglu MG, Kabay SC, Güven G (2011) The clinical evaluation of the oral status in Alzheimer-type dementia patients. Gerodontology 28:302–306. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2010.00401.x

Jones JA, Lavallee N, Alman J, et al. (1993) Caries incidence in patients with dementia. Gerodontology 10:76–82. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.1993.tb00086.x

Kossioni AE, Kossionis GE, Polychronopoulou A (2012) Oral health status of elderly hospitalised psychiatric patients. Gerodontology 29:272–83. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00633.x

Luo J, Wu B, Zhao Q, et al. (2015) Association between tooth loss and cognitive function among 3063 Chinese older adults: a community-based study. PLoS One 10:e0120986. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120986

Minakuchi S, Takaoka S, Shimoyama K, Uematsu H (2006) Factors affecting denture use in some institutionalized elderly people. Spec Care Dent 26:101–105. doi:10.1111/j.1754-4505.2006.tb01431.x

Nordenram G, Ryd-Kjellen E, Johansson G, et al. (1996) Alzheimer’s disease, oral function and nutritional status. Gerodontology 13:9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.1996.tb00145.x

Ribeiro GR, Costa JLR, Bovi Ambrosano GM, Rodrigues Garcia RCM (2012) Oral health of the elderly with Alzheimer’s disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 114:338–343. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2012.03.028

Srisilapanan P, Jai-Ua C (2013) Oral health status of dementia patients in Chiang Mai Neurological Hospital. J Med Assoc Thail 96:351–357

Sumi Y, Ozawa N, Michiwaki Y, et al. (2012) Oral conditions and oral management approaches in mild dementia patients. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 49:90–98

Syrjälä A-MH, Ylöstalo P, Ruoppi P, et al. (2012) Dementia and oral health among subjects aged 75 years or older. Gerodontology 29:36–42. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2010.00396.x

Warren JJ, Chalmers JM, Levy SM, et al. (1997) Oral health of persons with and without dementia attending a geriatric clinic. Spec Care Dent 17:47–53. doi:10.1111/j.1754-4505.1997.tb00866.x

Zenthöfer A, Schröder J, Cabrera T, et al (2014) Comparison of oral health among older people with and without dementia. Community Dent Health 31:27–31

Zenthöfer A, Cabrera T, Rammelsberg P, Hassel AJ (2016) Improving oral health of institutionalized older people with diagnosed dementia. Aging Ment Health 20:303–8. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1008986

Nishiyama Y (2005) Changes of general and oral health status of elderly patients receiving home-visit dental services. Kōkūbyō Gakkai zasshi J Stomatol Soc Japan 72:172–182

Chalmers J, Carter K, Spencer A (2004) Oral health of Adelaide nursing home residents: longitudinal study. Australas J Ageing 23:63–70. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6612.2004.00019.x

Chalmers JM, Carter KD, Spencer AJ (2005) Caries incidence and increments in Adelaide nursing home residents. Spec Care Dent 25:96–105. doi:10.1111/j.1754-4505.2005.tb01418.x

Hopcraft MS, Morgan MV, Satur JG, Wright FAC (2012) Edentulism and dental caries in Victorian nursing homes. Gerodontology 29:e512–e519. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00510.x

Kim J-M, Stewart R, Prince M, et al (2007) Dental health, nutritional status and recent-onset dementia in a Korean community population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:850–5. doi:10.1002/gps.1750

American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, third edition (DSM-III), 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR), 4th ed. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349

World Health Organization (1992) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva World Heal. Organ

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. (2011) The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 7:263–269. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group* under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34:939–939. doi:10.1212/WNL.34.7.939

Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. (2001) Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 56:1143–1153. doi:10.1212/WNL.56.9.1143

Morris JC (1993) The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43:2412–2414

Hodkinson HM (2012) Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing 41:iii35–iii40. doi:10.1093/ageing/afs148

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) Mini-mental state. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

Hartmaier SL, Sloane PD, Guess HA, Koch GG (1994) The MDS cognition scale: a valid instrument for identifying and staging nursing home residents with dementia using the minimum data set. J Am Geriatr Soc 42:1173–1179

Larmas M (2010) Has dental caries prevalence some connection with caries index values in adults? Caries Res 44:81–84. doi:10.1159/000279327

Klein H, Palmer CEKJ (1938) Dental status and dental needs of elementary school children. Public Heal Rep 53:751–755

Bödecker C (1939) The modified dental caries index. J Am Dent Assoc 26:1453–1460

Hamid T, Ataollahi Eshkoor S, Mun CY, Nudin SSH (2014) Association between dentures and the rate of falls in dementia. Med Devices Evid Res 7:225. doi:10.2147/MDER.S63220

de Siqueira SRDT, de Souza RT, Teixeira MJ, et al. (2010) Oral infections and orofacial pain in Alzheimer’s disease case report and review. Dement Neuropsychol 4:145–150

Chalmers J, Pearson A (2005) Oral hygiene care for residents with dementia: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 52:410–419. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03605.x

Chalmers JM, Ettinger RL (2008) Public health issues in geriatric dentistry in the United States. Dent Clin N Am 52:423–446. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2007.12.004

Chiappelli F, Bauer J, Spackman S, et al. (2002) Dental needs of the elderly in the 21st century. Gen Dent 50:358–363

Georg D (2006) Improving the oral health of older adults with dementia/cognitive impairment living in a residential aged care facility. Int J Evid Based Healthc 4:54–61. doi:10.1111/j.1479-6988.2006.00032.x

Ghezzi EM, Chávez EM, Ship JA (2000) General anesthesia protocol for the dental patient: emphasis for older adults. Spec Care Dentist 20:81–92

Kocaelli H, Yaltirik M, Yargic LI, Ozbas H (2002) Alzheimer’s disease and dental management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 93:521–524. doi:10.1067/moe.2002.123538

Mancini M, Grappasonni I, Scuri S, Amenta F (2010) Oral health in Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Curr Alzheimer Res 7:368–373

Pearson A, Chalmers J (2004) Oral hygiene care for adults with dementia in residential aged care facilities. JBI Reports 2:65–113. doi:10.1111/j.1479-6988.2004.00009.x

Rejnefelt I, Andersson P, Renvert S (2006) Oral health status in individuals with dementia living in special facilities. Int J Dent Hyg 4:67–71. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5037.2006.00157.x

Jablonski RA, Kolanowski A, Therrien B, et al. (2011) Reducing care-resistant behaviors during oral hygiene in persons with dementia. BMC Oral Health 11:30. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-11-30

Nordenram G, Ryd-kjellkn E, Ericsson K, Winblad B (1997) Dental management of Alzheimer patients. A predictive test of dental cooperation in individualized treatment planning. Acta Odontol Scand 55:148–154

Ship J, Decarli C (1990) Diminished submandibular salivary flow in dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Gerontol 45:61–66

Arrivé E, Letenneur L, Matharan F, et al. (2012) Oral health condition of French elderly and risk of dementia: a longitudinal cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 40:230–238. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00650.x

Lee KH, Wu B, Plassman BL (2015) Dental care utilization among older adults with cognitive impairment in the USA. Geriatr Gerontol Int 15:255–260. doi:10.1111/ggi.12264

Jablonski RA, Therrien B, Mahoney EK, et al. (2011) An intervention to reduce care-resistant behavior in persons with dementia during oral hygiene: a pilot study. Spec Care Dent 31:77–87. doi:10.1111/j.1754-4505.2011.00190.x

Willumsen T, Karlsen L, Naess R, et al. (2012) Are the barriers to good oral hygiene in nursing homes within the nurses or the patients? Gerodontology 29:e748–e755. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00554.x

Hsu K, Shuman SK, Hamamoto DT, Hodges JS, Feldt KS (2007) The application of facial expressions to the assessment of orofacial pain in cognitively impaired older adults. J Am Dent Assoc 138(7):963–9

Felton DA (2009) Edentulism and comorbid factors. J Prosthodont 18:88–96. doi:10.1111/j.1532-849X.2009.00437.x

Kandelman D, Petersen PE, Ueda H (2008) Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Spec Care Dent 28:224–236. doi:10.1111/j.1754-4505.2008.00045.x

Gao X-L, McGrath C (2011) A review on the oral health impacts of acculturation. J Immigr Minor Health 13:202–213. doi:10.1007/s10903-010-9414-9

Fiske J, Frenkel H, Griffiths J, et al. (2006) Guidelines for the development of local standards of oral health care for people with dementia. Gerodontology 23(Suppl 1):5–32. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2006.00140.x

Kalsbeek H, Baat de C, Kivit MM, Kleijn- de Vraknrijker MW (2000) Mondgezondheid van thuiswonende ouderen 1. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelk 107:499–504

Langlois NEI, Byard RW (2015) Dentures in dementia: a two-edged sword. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 11:606–608. doi:10.1007/s12024-015-9683-7

Santacruz KS, Swagerty D (2001) Early diagnosis of dementia. Am Fam Physician 63:703–13, 717–8. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2001/0215/p703.html

World Health Organization (2008) ICD-10 International Statistical Classificatrion of Diseases and Related Health Problems. WHO Libr. Cat. Data 2

Reisberg B (2006) Diagnostic criteria in dementia: a comparison of current criteria, research challenges, and implications for DSM-V. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 19:137–146. doi:10.1177/0891988706291083

Kester MI, Scheltens P (2009) Dementia: the bare essentials. Pract Neurol 9:241–251. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2009.182477

Mehta A, Article LR, Mehta A (2012) Comprehensive review of caries assessment systems developed over the last decade. RSBO 9:316–321

Bödecker CFBH (1931) A practical index of the varying susceptibility to dental caries in man. Dent Cosm 77:707–716

Mehta A (2012) Comprehensive review of caries assessment systems developed over the last decade. RSBO 9:316–321

Inaba A, Young C, Shields D (2011) Biting for attention: a case of dental discomfort manifesting in behavioural problems. Psychogeriatrics 11:242–243. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8301.2011.00374.x

Achterberg WP, Pieper MJC, van Dalen-Kok AH, et al. (2013) Pain management in patients with dementia. Clin Interv Aging 8:1471–1482. doi:10.2147/CIA.S36739

Scherder E, Herr K, Pickering G, et al. (2009) Pain in dementia. Pain 145:276–278. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2009.04.007

Scherder EJA, Sergeant JA, Swaab DF (2003) Pain processing in dementia and its relation to neuropathology. Lancet Neurol 2:677–686

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Eiko Yoshida of the Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU), Tokyo, Japan for her help with the assessment of the Japanese articles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

The work was supported by Alzheimer Nederland, Amstelring, Fonds NutsOhra, Roomsch Catholijk Oude Armen Kantoor (RCOAK), Stichting Beroepsopleiding Huisartsen (SBOH), and Stichting Henriëtte Hofje.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Delwel, S., Binnekade, T.T., Perez, R.S.G.M. et al. Oral health and orofacial pain in older people with dementia: a systematic review with focus on dental hard tissues. Clin Oral Invest 21, 17–32 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-016-1934-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-016-1934-9