Abstract

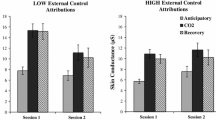

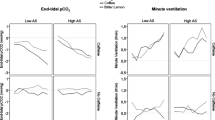

The current study examined the interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity (AS; fear of anxiety and anxiety-related sensations) and menstrual cycle phase (premenstrual phase vs. follicular phase) on panic-relevant responding (i.e., cognitive and physical panic symptoms, subjective anxiety, and skin conductance level). Women completed a baseline session and underwent a 3-min 10 % CO2-enriched air biological challenge paradigm during her premenstrual and follicular menstrual cycle phases. Participants were 55 women with no current or past history of panic disorder recruited from the general community (M age = 26.18, SD = 8.9) who completed the biological challenge during both the premenstrual and follicular cycle phases. Results revealed that women higher on AS demonstrated increased cognitive panic symptoms in response to the challenge during the premenstrual phase as compared to the follicular phase, and as compared to women lower on AS assessed in either cycle phase. However, the interaction of AS and menstrual cycle phase did not significantly predict physical panic attack symptoms, subjective ratings of anxiety, or skin conductance level in response to the challenge. Results are discussed in the context of premenstrual exacerbations of cognitive, as opposed to physical, panic attack symptoms for high AS women, and the clinical implications of these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Additional models were run including a variable indicating which menstrual phase was tested first to examine whether the ordering influenced response, and including a variable indicating whether or not the participant completed one or both laboratory visits. These factors did not predict any of the outcomes and were not included in any of the final models. Additionally, a total of three participants (5.5 %) met criteria for PMDD, and all analyses were run including PMDD diagnostic status as a covariate. Results did not vary as a function of PMDD diagnosis, therefore, final models presented in this manuscript do not include PMDD diagnosis as a covariate.

References

Asso D (1983) The real menstrual cycle. Wiley, New York

Barlow DH (2002) Anxiety and its disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic, 2nd edn. Guilford, New York

Barlow DH, Brown TA, Craske MG (1994) Definitions of panic attacks and panic disorder in the DSM-IV: implications for research. J Abnorm Psychol 103:553–564

Barnard K, Frayne SM, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM (2003) Health status among women with menstrual symptoms. J Womens Health 12:911–919

Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Schmidt NB (2009) Laboratory test of a novel structural model of anxiety sensitivity and panic vulnerability. Behav Ther 40:171–180

Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR (1997) Premenstrual syndrome: evidence for symptom stability across cycles. Am J Psychiatry 154:1741–1746

Borenstein JE, Dean BB, Leifke E, Korner P, Yonkers KA (2007) Differences in symptom scores and health outcomes in premenstrual syndrome. J Womens Health 16:1139–1144

Breier A, Charney DS, Heninger GR (1986) Agoraphobia with panic attacks. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43:1029–1036

Chrisler JC, Caplan P (2002) The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde: how PMS became a cultural phenomenon and a psychiatric disorder. Annu Rev Sex Res 13:274–306

Crawford JR, Henry JD (2004) The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 43:245–265

Donnell CD, McNally RJ (1989) Anxiety sensitivity and history of panic as predictors of response to hyperventilation. Behav Res Ther 27:325–332

Eifert GH, Zvolensky MJ, Sorrell JT, Hopke DR, Lejuez CW (1999) Predictors of self-reported anxiety and panic symptoms: an evaluation of anxiety sensitivity, suffocation fear, heart-focused anxiety, and breath-holding duration. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 21:293–305

Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W (2006) Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Arch Womens Ment Health 9:41–49

Epting LK, Overman WH (1998) Sex-sensitive tasks in men and women: a search for performance fluctuations across the menstrual cycle. Behav Neurosci 112:1304–1317

First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J (1994) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders-non-patient edition. Biometrics Research Department, New York

Follesa P, Serra M, Cagetti E, Pisu MG, Porta S, Floris S, Massa F, Sanna E, Biggio G (2000) Allopregnanolone synthesis in cerebellar granule cells: roles in regulation of GABAA receptor expression and function during progesterone treatment and withdrawal. Mol Pharmacol 57:1262–1270

Foot M, Koszycki D (2004) Gender differences in anxiety-related traits in patients with panic disorder. Depress Anxiety 20:123–130

Forsyth JP, Eifert GH (1998) Response intensity in content-specific fear conditioning comparing 20 % versus 13 % CO2-enriched air as unconditioned stimuli. J Abnorm Psychol 107:291–304

Freeman EW (2003) Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: definitions and diagnosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 28:25–37

Gonda X, Telek T, Juhasz G, Lazary J, Vargha A, Bagdy G (2008) Patterns of mood changes throughout the reproductive cycle in healthy women without premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32:1782–1788

Halbreich U (2003) The etiology, biology, and evolving pathology of premenstrual symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology 28:55–99

Halbreich U, Endicott J, Goldstein S, Nee J (1986) Premenstrual changes and changes in gonadal hormones. Acta Psychiatr Scand 74:576–586

Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn LS (2003) The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology 28:1–23

Harrison WM, Sandberg D, Gorman JM, Fyer M, Nee J, Uy J, Endicott J (1989) Provocation of panic with carbon dioxide inhalation in patients with premenstrual dysphoria. Psychiatry Res 27:183–192

Karekla M, Forsyth JP, Kelly MM (2004) Emotional avoidance and panicogenic responding to a biological challenge procedure. Behav Ther 35:725–746

Kaspi SP, Otto MW, Pollack MH, Eppinger S, Rosenbaum JF (1994) Premenstrual exacerbation of symptoms in women with panic disorder. J Anxiety Disord 8:131–138

Kent JM, Papp LA, Martinez JM, Browne ST, Coplan JD, Klein DF, Gorman JM (2001) Specificity of panic response to CO2 inhalation in panic disorder: a comparison with major depression and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am J Psychiatry 158:58–67

Le Melledo JM, Merani S, Koszycki D et al (1999) Sensitivity to CCK-4 in women with and without premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) during their follicular and luteal phases. Neuropsychopharmacology 20:81–91

Lejuez CW, Forsyth JP, Eifert GH (1998) Devices and methods for administering carbon dioxide-enriched air in experimental and clinical settings. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 29:239–248

Li W, Zinbarg RE (2007) Anxiety sensitivity and panic attacks: a 1-year longitudinal study. Behav Modif 31:145–161

Logue CM, Moos RH (1986) Perimenstrual symptoms: prevalence and risk factors. Psychosom Med 48:388–414

Maller RG, Reiss S (1992) Anxiety sensitivity in 1984 and panic attacks in 1987. J Anxiety Disord 6:241–247

McNally RJ (1996) Cognitive bias in the anxiety disorders. Nebr Symp Motiv 43:211–250

McNally RJ (2002) Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 52:938–946

McNally RJ, Lorenz M (1987) Anxiety sensitivity in agoraphobics. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 18:3–11

Nillni YI, Rohan KJ, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ (2010) Premenstrual distress predicts panic-relevant responding to a CO2 challenge among young adult females. J Anxiety Disord 24:416–422

Nillni YI, Toufexis DJ, Rohan KJ (2011) Anxiety sensitivity, the menstrual cycle and panic disorder: a putative neuroendocrine and psychological connection. Clin Psychol Rev 31:1183–1191

Pearlstein T, Stone AB (1998) Premenstrual syndrome. Psychiatr Clin North Am 21:577–590

Perna G, Brambilla F, Aranio C, Bellodi L (1995) Menstrual cycle-related sensitivity to 35 % CO2 in panic patients. Biol Psychiatry 37:528–532

Peterson RA, Heilbronner RL (1987) The anxiety sensitivity index: construct validity and factor analytic structure. J Anxiety Disord 1:117–121

Reiss S, McNally RJ (1985) The expectancy model of fear. In: Reiss S, Bootzin RR (eds) Theoretical issues in behavior therapy. Academic, New York, pp 107–122

Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ (1986) Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 24:1–8

Rubinow DR, Hoban MC, Grover GN, Galloway DS, Roy-Byrne P, Andersen R, Merriam GR (1988) Changes in plasma hormones across the menstrual cycle in patients with menstrually related mood disorder and in control subjects. Am J Obstet Gynecol 158:5–11

Salimetrics (2010) Salivary progesterone enzyme immunoassay kit. State College, PA

Sanderson WC, Rapee RM, Barlow DH (1988) Panic induction via inhalation of 5.5 % CO2 enriched air: a single subject analysis of psychological and physiological effects. Behav Res Ther 26:333–335

Sanderson WC, Rapee RM, Barlow DH (1989) The influence of an illusion of control on panic attacks induced via inhalation of 5.5 % carbon dioxide-enriched air. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46:157–162

Schmidt NB, Koselka M (2000) Gender differences in patients with panic disorder: evaluating cognitive mediation of phobic avoidance. Cogn Ther Res 24:533–550

Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Grover GN, Muller KL, Merriam GR, Rubinow DR (1991) Lack of effect of induced menses on symptoms in women with premenstrual syndrome. N Engl J Med 324:1174–1179

Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Maner JK (2006) Anxiety sensitivity: prospective prediction of panic attacks and Axis I pathology. J Psychiatr Res 40:691–699

Schmidt NB, Eggleston AM, Woolaway-Bickel K, Fitzpatrick KK, Vasey MW, Richey JA (2007) Anxiety sensitivity amelioration training (ASAT): a longitudinal primary prevention program targeting cognitive vulnerability. J Anxiety Disord 21:302–319

Shirtcliff EA, Reavis R, Overman WH, Granger DA (2001) Measurement of gonadal hormones in dried blood spots versus serum: verification of menstrual cycle phase. Horm Behav 39:258–266

Sigmon ST, Fink CM, Rohan KJ, Hotovy LA (1996) Anxiety sensitivity and menstrual cycle reactivity: psychophysiological and self-report differences. J Anxiety Disord 10:393–410

Sigmon ST, Dorhofer DM, Rohan KJ, Hotovy LA, Boulard NE, Fink CM (2000) Psychophysiological, somatic, and affective changes across the menstrual cycle in women with panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 68:425–431

Sigmon ST, Whitcomb-Smith SR, Rohan KJ, Kendrew JJ (2004) The role of anxiety level, coping styles, and cycle phase in menstrual distress. J Anxiety Disord 18:177–191

Smith SS, Ruderman Y, Frye C, Homanics G, Yuan M (2006) Steroid withdrawal in the mouse results in axiogenic effects of 3α5α-THP: a possible model of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychopharmacology 186:323–333

Spira AP, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH, Feldner MT (2004) Avoidance-oriented coping as a predictor of panic-related distress: a test using biological challenge. J Anxiety Disord 18:309–323

Stein MB, Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR, Uhde TW (1989) Panic disorder and the menstrual cycle: panic disorder patients, healthy control subjects, and patients with premenstrual syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 146:1299–1303

Stewart SH, Taylor S, Baker JM (1997) Gender difference in dimensions of anxiety sensitivity. J Anxiety Disord 11:179–200

Taylor S, Koch WJ, McNally RJ (1992) How does anxiety sensitivity vary across the anxiety disorders? J Anxiety Disord 6:249–259

van Beek N, Griez E (2003) Anxiety sensitivity in first-degree relatives of patients with panic disorder. Behav Res Ther 41:949–957

Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ, Gibson LE, Lynch TR, Leen-Feldner EW, Feldner MT, Bernstein A (2006) Affect intensity: association with anxious and fearful responding to bodily sensations. J Anxiety Disord 20:192–206

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1063–1070

Wittchen H, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P (2002) Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol Med 32:119–132

Wolpe J (1958) Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH (2000) A review of psychological factors/processes affecting anxious responding during voluntary hyperventilation and inhalations of carbon dioxide-enriched air. Clin Psychol Rev 21:375–400

Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Eifert GH (1998) The role of control in anxious responding: an experimental test using repeated administrations of 20 % CO2 enriched air. Behav Ther 29:193–209

Zvolensky MJ, Kotov R, Antipova AV, Schmidt NB (2005) Diathesis stress model for panic-related distress: a test in a Russian epidemiological sample. Behav Res Ther 43:521–532

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Dissertation grant awarded to Yael I. Nillni (1R36MH086170-01A1). We would like to thank Dr. Alessandra Rellini, Dr. Keith Burt, and Dr. Magdalena Naylor for their comments on a prior version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nillni, Y.I., Rohan, K.J. & Zvolensky, M.J. The role of menstrual cycle phase and anxiety sensitivity in catastrophic misinterpretation of physical symptoms during a CO2 challenge. Arch Womens Ment Health 15, 413–422 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0302-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0302-2