Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to identify and descriptively compare the red flags endorsed in guidelines for the detection of serious pathology in patients presenting with low back pain to primary care.

Method

We searched databases, the World Wide Web and contacted experts aiming to find the multidisciplinary clinical guideline in low back pain in primary care, and selected the most recent one per country. We extracted data on the number and type of red flags for identifying patients with higher likelihood of serious pathology. Furthermore, we extracted data on whether or not accuracy data (sensitivity/specificity, predictive values, etc.) were presented to support the endorsement of specific red flags.

Results

We found 21 discrete guidelines all published between 2000 and 2015. One guideline could not be retrieved and after selecting one guideline per country we included 16 guidelines in our analysis from 15 different countries and one for Europe as a whole. All guidelines focused on the management of patients with low back pain in a primary care or multidisciplinary care setting. Five guidelines presented red flags in general, i.e., not related to any specific disease. Overall, we found 46 discrete red flags related to the four main categories of serious pathology: malignancy, fracture, cauda equina syndrome and infection. The majority of guidelines presented two red flags for fracture (‘major or significant trauma’ and ‘use of steroids or immunosuppressors’) and two for malignancy (‘history of cancer’ and ‘unintentional weight loss’). Most often pain at night or at rest was also considered as a red flag for various underlying pathologies. Eight guidelines based their choice of red flags on consensus or previous guidelines; five did not provide any reference to support the choice of red flags, three guidelines presented a reference in general, and data on diagnostic accuracy was rarely provided.

Conclusion

A wide variety of red flags was presented in guidelines for low back pain, with a lack of consensus between guidelines for which red flags to endorse. Evidence for the accuracy of recommended red flags was lacking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low back pain remains a common condition among primary care patients with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 13.8 % for chronic pain and 80 % for any episode of pain [1–3]. European guidelines for the management of low back pain in primary care define low back pain as “pain and discomfort” localized below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without leg pain. Nonspecific low back pain is commonly defined as low back pain without any known pathology [4]. Although nonspecific low back pain accounts for about 85–90 % of back pain [5–7], the remaining patients may have neurologic impairments (e.g., spinal stenosis, radiculopathy) or serious underlying diseases (e.g., malignancies, fractures), of which the latter necessitates timely and accurate diagnosis [6, 7].

Serious pathology in patients presenting with low back pain includes malignancy, spinal fractures, cauda equina syndrome (CES), infection or aortic aneurisms. Spinal malignancy and vertebral fracture are the most frequent serious pathologies of the spine [8]. However, the absolute magnitude of occurrence may be regarded as rare. Among patients with low back pain presenting in primary care less than 1 % will have spinal malignancy (primary vertebral tumor or vertebral metastasis) and about 4 % will have spinal fracture [5, 9]. CES or spinal infections are even rarer, with an estimated prevalence of 0.04 and 0.01 %, respectively, among patients with low back pain [5, 9]. The spine is the most common bony site for musculoskeletal tumors. The majority of spinal malignancies are the result of metastases of other tumors in the body, mainly from breast, lung or prostate cancer [10]. Vertebral compression fractures occur in almost 25 % of all postmenopausal women and the prevalence of compression fractures linearly increases with advancing age, up to 40 % in women 80 years of age [11].

Clinicians are advised by guidelines to evaluate serious underlying pathology by checking for red flags (or alarm signals) during the history taking and physical examination [12]. The presence of red flags may indicate underlying serious pathology in patients with low back pain. Current guidelines often present a list of red flags, which are considered to be associated with an increased risk of the presence of underlying serious pathology in the spine, often without consideration given to the diagnostic accuracy of the red flag (test). While most guidelines recommend screening for red flags, there is variation in which red flags are endorsed, and there exists heterogeneity in precise definitions of the red flags (e.g. ‘trauma’, ‘severe trauma’, ‘major trauma’). An overview of recommended red flags in the guidelines is lacking. The purpose of this study was to identify and compare the red flag recommendations in current guidelines for the detection of medically serious pathology in patients presenting with low back pain.

Method

Design

Overview of recommendations on red flag screening in low back pain guidelines.

Search strategy

We searched for clinical guidelines in primary health care concerning adults with low back pain (date of last search January 30, 2016). Our starting point was a previously published review article including 15 national and international guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of low back pain [12]. First, we checked for updates of these 15 guidelines. Additionally, we searched for other clinical practice guidelines using electronic databases: Medline, PEDro (key words: low back pain, practice guidelines, clinical guidelines), National Guideline Clearinghouse (http://www.guideline.gov; key word: low back pain), and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (http://www.nice.org.uk; key word: low back pain). Furthermore, we performed searches via Google, performed snowballing and citation tracking on publications found and consulted experts in the field. The search was aimed at finding all the clinical guidelines that exist. No language or date restriction was applied. We defined ‘guideline’ as: “… contains systematically developed statements including recommendations intended to optimize patient care and assist physicians and/or other health care practitioners and patients to make decisions about appropriate health care for low back pain under the auspices of a medical specialty association; relevant professional society; public or private organization” (according to the National Guideline Clearinghouse). When one country had more than one guideline, we selected the most recent multidisciplinary guideline.

Data extraction

We extracted data on the number and type of red flags for serious pathology for each guideline using a standardized form. For each red flag, we scored if the red flag was supported by the literature presenting its diagnostic accuracy (e.g., data on sensitivity/specificity, predictive values, etc.), if it was supported by consensus of the guideline committee only, or if no information was given to support the endorsement of red flags. One author (NP) extracted the data, which were checked by a second (APV). The data were summarized using tables.

Results

Search results

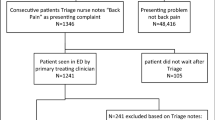

First, of the original 15 guidelines of previously published review article [12], we excluded the European guideline for chronic low back pain [13], given that red flags were presented in the European guideline for acute low back pain only [4]. Eight countries updated their guideline (Austria, Canada, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and United States) [17–24]; of three countries, we found more than one updated guideline (Austria, Netherlands, and United States). We found two updated guidelines from Austria including an update of a multidisciplinary guideline from 2007 and one specifically for radiologists [25] of which we selected the multidisciplinary one [17]. The updated guidelines from The Netherlands included a multidisciplinary guideline and one specifically for physiotherapists [26] of which we selected the multidisciplinary one [21]. The United States had two multidisciplinary guidelines [24, 27] and one specifically for physiotherapists [28] of which we selected for this overview the latest multidisciplinary guideline [24] linked to a website [29]. The guidelines of Finland and Norway were not available in English, so colleagues were contacted to extract the relevant data.

Next, we performed a broad search aiming to identify additional guidelines. In total, we identified 21 guidelines, of which four were excluded (see above) as we selected one guideline per country. We found three new guidelines (Philippines, Malaysia, and Mexico) of which one guideline (Mexico) [14] could not be retrieved [15, 16]. Finally, 16 discrete guidelines were included in this review (see Table 1).

Description of the guidelines

The guidelines were published between 2000 (France) and 2015 (Finland), with the publication date of one guideline unknown (Malaysia). The target population was mostly adults (>15 or 18 years) with low back pain. Nine guidelines used the term nonspecific low back pain, three guidelines also included people with radiculopathy, four guidelines specifically focused on patients with acute low back pain (defined as a duration less than 3 months), and one guideline included patients with acute and/or recurrent low back pain (New Zealand) (see Table 1).

Red flags

All guidelines recommended screening patients for suspected serious pathologies by using red flags. Eight guidelines presented red flags for various forms of serious underlying disease specifically (Australia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, United Kingdom, USA) [19, 20, 24, 30–33]; one guideline combined red flags for malignancy and infection (Canada) [18]; two guidelines presented general red flags, but separately for cauda equina syndrome (Europe, New Zealand) [4, 34]; and five guidelines presented red flags without targeting a specific underlying pathology (Austria, Malaysia, Norway, Philippine, Spain) [15–17, 22, 23].

The pathologies most commonly referred to in the guidelines were: malignancy (9 guidelines); fracture (9 guidelines) of which one guideline focused on compression fractures only (Finland), and three guidelines distinguished between traumatic and osteoporotic fractures (Canada, Netherlands, United States); infection (8 guidelines) of which one focused only on ankylosing spondylitis (Netherlands), two guidelines separately focused on infection and spondyloarthropathies (Italy, United States) and two on infection and ankylosis spondylitis (Canada, France); cauda equina syndrome (7 guidelines); aneurism (3 guidelines); myelopathy (United States) and severe spondylolisthesis (Netherlands). We found 46 different guideline endorsed red flags for malignancy, fractures, infection and cauda equina syndrome (see Table 2).

None of the guidelines provided a detailed definition of each red flag nor a precise description of when a red flag could be considered positive, e.g., when does a patient have ‘osteoporosis’ or ‘loading pain’. For the presentation, we clustered red flags when the wording suggested a comparable definition or description, e.g., some guidelines state as a red flag for a fracture the ‘use of steroids’ or ‘corticosteroid use’, while others add the prefix ‘systemic’, ‘chronic’ or ‘prolonged’. Others categorize corticosteroid use with ‘immunosuppressive use’.

Malignancy

There are a wide variety of recommended red flags for malignancy. In total, 14 red flags were specifically related to malignancy. Two red flags were mentioned in almost all guidelines: a ‘history of cancer’ was included in all guidelines, and ‘unexplained or unintentional weight loss’ was included in all but three guidelines (Spain, United Kingdom and United States). Almost all guidelines mentioned pain as a red flag, but the description of the kind of pain differed. Most often ‘pain at rest’ or ‘pain at night’ was considered as a red flag. Nine red flags for malignancy were mentioned in a single guideline only: ‘multiple cancer risk factors (unspecified)’ and ‘strong clinical suspicion’ (United States), ‘reduced appetite’ and ‘rapid fatigue’ (Germany), ‘elevated ESR’ and ‘general malaise’ (The Netherlands), ‘fever’, ‘paraparesis’ and ‘progressive symptoms’ (Finland). One guideline presents a combination of red flags for malignancy: ‘Patient over 50 (particularly over 65), with first episode of severe back pain and other risk factors for malignancy, such as history of cancer/carcinoma in the last 15 years, unexplained weight loss, failure of conservative care (4 weeks)’ (Canada), see Table 1.

Fracture

In total, 11 red flags were considered to be specifically related to fractures. All but one guideline (United Kingdom) mentioned ‘major or significant trauma’ as a red flag, and ‘use of steroids or immunosuppressors’ was mentioned as a red flag in nine guidelines. Seven guidelines mentioned ‘older age’ as a red flag, but the cut-off varied between 50 and over 70 years. Five red flags for fracture were mentioned in a single guideline only: ‘previous fractures’ (Italy), ‘low body weight’ and ‘increased thoracic kyphosis’ (The Netherlands), ‘structural deformity’ (Canada) and ‘minor trauma’ (Germany). Three guidelines mentioned female gender as a red flag specifically for osteoporotic/compression fractures (Italy, Netherlands, and United Kingdom). Two guidelines presented a combination of red flags to be related to (compression) fractures: ‘minor trauma if age is over 50 and there is a history of osteoporosis and corticosteroid use’ (Australia) or ‘severe onset of pain with minor trauma, age >50, prolonged steroid intake or structural deformity (for compression fracture)’ (Canada).

Infection

Overall, 13 red flags were recommended in relation to infection. The most frequently mentioned red flags were: fever (12 guidelines), use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressant therapy (10 guidelines) and intravenous drug abuse (11 guidelines). Five guidelines mentioned pain as red flag: ‘pain worse at night’ (France); ‘intense nocturnal pain’ (Germany); ‘night and rest pain’ (Italy); ‘fever/chills in addition to pain with rest or at night’ (United States) or ‘bone tenderness over the lumbar spinous process’ (Australia).

Cauda equina syndrome

Nine red flags were recommended in relation to cauda equina syndrome (CES), of which two were frequently mentioned: ‘saddle anesthesia (perineal numbness)’ and ‘(sudden onset of) bladder dysfunction’, both in nine guidelines. Only one red flag (‘sciatica’) is endorsed by one guideline (France).

Red flags unrelated to specific disease

Seven guidelines presented 23 red flags unrelated to a specific disease (Austria, Europe, New Zealand, Norway, Philippine, Spain, Malaysia). Of these red flags, some were endorsed for a specific disease by other guidelines; 9 were endorsed for malignancy, 4 for fracture, 3 for infection and 6 for CES. In total, three unique red flags were presented and 6 unique pain items of which ‘pain under 20 or over 50 years’ and ‘thoracic pain’ were the most presented in 6 and 5 guidelines, respectively, see Table 3.

Level of evidence of red flags in the guidelines

Nine guidelines (Austria, Canada, Europe, Finland, Germany, Norway, Philippine, Spain, United States) based their recommendations for red flags on previous guidelines, of which two also included additional references (Europe, United States) and one explicitly stated that there was a consensus procedure (Germany), see Table 1. Four guidelines did not present any reference supporting their choice of red flags (Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, United Kingdom); two guidelines presented references to support the choice of red flags (Australia, Malaysia), see Table 1. One guideline (France) presented diagnostic accuracy data (sensitivities and specificities) for the individual red flags. In the short version of the French guideline they only presented these data for two red flags for malignancy (‘history of malignancy’, ‘unexplained weight loss’), while in their full paper all published accuracy data for red flags for malignancy and ankylosing spondylitis were presented.

Discussion

Main findings

We included 16 discrete guidelines for the management of patients with low back pain in the primary care setting presenting 46 different red flags for the four main categories of serious underlying pathologies (malignancy, fracture, infection and CES). Five guidelines endorsed red flags without targeting a specific pathology. Overall almost all guidelines endorsed two red flags for malignancy (‘history of cancer’ and ‘unintentional weight loss’) and two for fracture (‘major or significant trauma’ and ‘use of steroids or immunosuppressors’). Red flags such as ‘pain at night’ or ‘at rest’ were recommended for various underlying pathologies. Existing accuracy data supporting the choice and endorsement of red flags was rarely used in the selected guidelines.

Comparison with the literature

Our findings that most guidelines vary in terms of the red flags endorsed, and contain little information on the diagnostic accuracy of the red flags, are in line with previous studies [12, 35, 36]. Although all guidelines present red flags and recommend their use to screen for serious pathology, only a few provide evidence of their accuracy. The American Pain Society presented an ‘Evidence review’ on the clinical evaluation and management of low back pain with a date of last search in July 2008 [37]. This report presents a clear overview of the known diagnostic accuracy of red flags for the detection of pathology including malignancy, fracture, infection and CES. Several guidelines have been developed or updated since [27, 38], but without presenting the level of evidence to endorse red flags as cited in the evidence report (or refer to it). For example, the United States guideline (2014) endorses a greater number of red flags, but seldom underpins their recommendations with evidence.

Change in evidence is one of the reasons for updating guidelines [39]. New evidence can prompt the update of a guideline, but our review suggests that evidence related to screening for serious pathology has not prompted update of the guidelines studied. One exception is the United States physiotherapy guideline (excluded as it was not multidisciplinary), which presents a comprehensive table with red flags and their accompanying diagnostic accuracy data were available [28].

A recent paper summarizing two Cochrane diagnostic systematic reviews found nine studies evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of in total 29 red flags for fracture and 24 for malignancy [8]. There were differences in the red flags that demonstrated diagnostic utility and those endorsed by guidelines. It makes sense that red flags that do not show acceptable diagnostic accuracy are not endorsed in guidelines. Nevertheless, most red flags endorsed by the guidelines have never been evaluated for their diagnostic accuracy; 8 out of 14 red flags for malignancy and 6 of the 11 red flags for fracture.

For malignancy, the systematic review concluded that only ‘history of cancer’ is based on acceptable validity; it increases the probability of having cancer from 0.7 % (pre-test) to 33 % (95 % CI 22–46 %) [8]. Nevertheless, this conclusion is based on one study set in primary care and another in an emergency department where 36 % of patients were referred to because of a significant trauma [40, 41]. It is argued that ‘history of cancer’ is not very useful as a red flag, as it does not consider the type of primary cancer or the time since diagnosis [42]. For example, a history of recent (less than 5 years) breast cancer might be a more useful red flag than a history of leukemia greater than 20 years ago.

According to the systematic review, the red flags ‘severe trauma’, ‘use of corticosteroids’, ‘older age’ and ‘presence of a contusion or abrasion’ each increased the probability of a fracture from 4 % (pre-test) to between 9 and 62 % [8]. Three of these red flags were most often mentioned in the guidelines, but one (‘presence of a contusion or abrasion’) was absent from all guidelines.

An Australian population-based prospective cohort study of 1172 consecutive patients presenting to primary care for low back pain calculated the increased probability of fracture when a combination of red flags were positive [43]. When any three of the red flags ‘female’, ‘age >70’, ‘severe trauma’, and ‘prolonged use of corticosteroids’ were present, the probability of fracture increased from 4 % (pre-test) to 90 % (95 % CI 34–99 %). Combining red flags to inform clinical decision-making remains largely unexplored in the literature. In addition, external validation of red flags used in combination to raise suspicion of disease is even more rare.

The European guideline reports explicitly “If any of these are present, further investigation (according to the suspected underlying pathology) may be required to exclude a serious underlying condition, e.g., infection, inflammatory rheumatic disease or cancer” [4]. Later in their guideline, the advice is diluted: “Individual ‘red flags’ do not necessarily link to specific pathology but indicate a higher probability of a serious underlying condition that may require further investigation. Multiple ‘red flags’ need further investigation.” Nevertheless, the majority of guidelines inferred that the presence of a red flag was absolute by recommending further diagnostic workup (e.g., advanced imaging). Given that up to 80 % of patients presenting to primary care may have at least one positive red flag [43], when combined with weak evidence in support of many red flags, this advice may cause harm to many patients through unnecessary imaging (increased radiation and health care costs), unnecessary alarming the patients (resulting in reduction of quality of life) and unnecessary treatment (including unnecessary surgery) [42, 44].

Strengths and weaknesses

For this overview, we searched for clinical guidelines. This required a broad and sensitive search of electronic databases, the World Wide Web and personal communication with experts in the field as most often clinical guidelines are made by (a combination of) professional bodies and published on national websites in their native languages. Not all guidelines have been translated into English, so it is possible that some non-English guidelines have been missed. Notwithstanding, we believe this would not have significantly influenced our conclusions. Furthermore, we selected a multidisciplinary guideline when more than one guideline per country was available. This resulted in an a priori selection of guidelines that might have influenced our conclusions. For instance, the United States physiotherapy guideline endorsed another set of red flags with accompanying diagnostic accuracy data where available, compared to the included multidisciplinary guideline [24, 28]. Hence, we have clustered red flags based on their assumed definition or description. Lack of standardization was evident when defining or describing red flags. For example, red flags related to nocturnal pain comprised ‘increasing pain at night’, ‘intense night pain’, ‘unbearable night and rest pain’, ‘pain at night not eased by prone laying’ or ‘pain with recrudescence at night’. Similarly, there was a range of age cut-off for suspicion of fracture (>50, >60, >70, and ‘older age’). This lack of standardization may introduce confusion for the clinician, reduce the ability to describe red flags, and decrease the accuracy of any pooled results. Nevertheless, we do not think this clustering has influenced our conclusions.

Future directions

We found a wide variety of red flags, a lack of standardized description, and an overall lack of (presentation of their) diagnostic accuracy supporting their use. This highlights the need for a (limited) core set of red flags, ideally underpinned with acceptable diagnostic accuracy and endorsed by all guidelines. Next, the conduct of high quality diagnostic accuracy studies with clear operational definitions for each red flag should be commenced to assess the validity of these red flags individually or in combination (diagnostic model). Furthermore, guidance for primary care clinicians on how to ask for red flags needs attention, as there appeared little consensus between physiotherapists in a small qualitative study [45]. Given that the risk of serious disease for patients who present to primary care with low back pain is already low (e.g., infection <0.1 %, cancer about 0.7 %), red flags are of limited use when ruling out pathology. This is in contrast to other diagnostic models such as the Ottawa ankle rule where a negative test result may decrease the probability of ankle fracture from about 15 % to less than 2 % [46–48]. Therefore, diagnostic models that demonstrate an increased ability to detect serious disease should be explored. Some diagnostic models of red flags for fracture have been developed to identify patients with a greater risk of a fracture (up to 90 %), but they are yet to be validated [43, 49].

Conclusion

A wide variety of red flags is presented in the various guidelines for low back pain. Most guidelines based their recommendations for red flags on consensus; hardly any guidelines presented the evidence for endorsing red flags.

References

Joines JD, McNutt RA, Carey TS, Deyo RA, Rouhani R (2001) Finding cancer in primary care outpatients with low back pain: a comparison of diagnostic strategies. J Gen Intern Med 16(1):14–23

Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, York J, Das A (2008) McAuley JH Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ 337:a171. doi:10.1136/bmj.a171

Frymoyer JW, Cats-Baril WL (1991) An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am 22:263–271

van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, Breen A, del Real MT, Hutchinson A et al (2006) European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 15:S169–S191

Jarvik JG, Deyo RA (2002) Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med 137(7):586–597

Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr, Shekelle P, Owens DK, Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians; American College of Physicians; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel (2007) Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med 147(7):478–491

Raison NT, Alwan W, Abbot A, Farook M, Khaleel A (2014) The reliability of red flags in spinal cord compression. Arch Trauma Res 3(1):e17850. doi:10.5812/atr.17850

Downie A, Williams CM, Henschke N, Hancock MJ, Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, Macaskill P, Irwig L, van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Maher CG (2013) Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: systematic review. BMJ 347:f7095. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7095

Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL (1992) What can the history and physical examination tell us about low back pain? JAMA 268(6):760–765

Van Goethem J, van den Hauwe L, Ozsarlak O, de Schepper AM, Parizel PM (2004) Spinal tumors. Eur J Radiol 50:159–176

Old JL, Calvert M (2004) Vertebral compression fractures in the elderly. Am Fam Phys 69(1):111–116

Koes B, Tulder M, Wei C, Lin C, Macedo G, McAuley J, Maher C (2010) An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 19:2075–2094

Brox JI, Cedraschi J, Hildebrandt J, Moffett F, KovacIs KI, Mannion AF (2006) European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J 15:S192–S300

Guevara-López U, Covarrubias-Gómez A, Elías-Dib J, Reyes-Sánchez A, Rodríguez-Reyna TS, Consensus Group of Practice Parameters to Manage Low Back Pain (2011) Practice guidelines for the management of low back pain. Consensus Group of Practice Parameters to Manage Low Back Pain. Cir Cir 79(3):264–279, 286–302

(2014) Low back pain management guideline. Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine. http://www.eparm.org/images/LOW-BACK-PAIN-Guideline.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016

Hussein AM, Choy Y, Singh D, Cardosa M, Mansor M, Hasnan N Malaysian low back pain management guideline Malaysian association for the study of pain, first edition. Available from: http://www.masp.org.my/index.cfm?&menuid=23. Accessed Feb 2016

(2003). http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/cp94.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016

Canada TOP (2011) TOP 2009 guideline for the evidence-informed primary care management of low back pain. Edmonton (AB): toward optimized practice. http://www.topalbertadoctors.org. Accessed Feb 2016

Pohjolainen T, Leinonen V, Frantén J, Haanpää M, Jousimaa J, Karppinen J, Kuukkanen T, Luoma K, Salmenkivi J, Osterman H, Malmivaara A, Päivitystiivistelmä (2015) Update on current care guideline: low back pain. Duodecim 131(1):92–94 (Review. Finnish. PubMed PMID: 26245063)

German Medical Association (BÄK); National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KBV); Association of Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) (2013) National Disease Management Guideline ‘Low back pain’—short version. Version 4. 2011 last amended. Available from: http://www.kreuzschmerz.versorgungsleitlinie/, http://www.versorgungsleitlinien.de, http://www.awmf-leitlinien.de. Accessed Feb 2016

Van Tulder MW, Custers JWH, de Bie RA, Hammelburg R, Hulshof CTJ, Kolnaar BGM, Kuijpers T, Ostelo RJWG, v Royen BJ, Sluiter A (2010) Ketenzorg richtlijn aspecifieke lage rugklachten. http://www.diliguide.nl/document/3272/ketenzorgrichtlijn-aspecifieke-lage-rugklachten.html. Accessed Feb 2016

Lærum E, Brox J, Werner EL (2010) Nasjonale kliniske retningslinjer. Vond rygg—fortsatt en klinisk utfordring. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen nr. 130:2248–51. http://www.formi.no/images/uploads/pdf/Formi_nett.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016

Latorre Marques E (2012) The treatment of low back pain and scientific evidence, low back pain. In: Norasteh AA (ed.) InTech. doi: 10.5772/33716. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/low-back-pain/the-treatment-of-low-back-pain-scientific-evidence. (ISBN: 978-953-51-0599-2). Accessed Feb 2016

(2014). https://intermountainhealthcare.org/ext/Dcmnt?ncid=522579081. Accessed Feb 2016

Kainberger F, Ebner W, Machold K, Redlich K, Schirmer M, Schüller-Weidekamm C (2012) Kreuzschmerz—Bildgebung rasch und richtig. http://www.rheumatologie.at/pdf/KreuzschmerzBroschuereDRUCK-06-12.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016

Staal JB, Hendriks EJM, Heijmans M, Kiers H, Lutgers-Boomsma AM, Rutten G, van Tulder MW, den Boer J, Ostelo R, Custers JWH (2013) KNGF richtlijn lagerug pijn. https://www.fysionet-evidencebased.nl/images/pdfs/richtlijnen/lage_rugpijn_2013/lage_rugpijn_verantwoording_en_toelichting.pdf

Goertz M, Thorson D, Bonsell J, Bonte B, Campbell R, Haake B, Johnson K, Kramer C, Mueller B, Peterson S, Setterlund L, Timming R (2012) Adult acute and subacute low back pain. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI), Bloomington

Delitto A, George SZ, van Dillen L, Whitman JM, Sowa G, Shekelle P, Denninger TR, Godges JJ (2012) Low back pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 42(4):A1–A57

Interactive website: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-low-back-pain-in-adults. Accessed Feb 2016

(2011) Update of Evidenz- und konsensusbasierte österreichische Leitlinien für das Management akuter und chronischer unspezifischer Kreuzschmerzen http://www.aekwien.at/aekmedia/UpdateLeitlinienKreuzschmerz_2011_0212.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016

Adorian D, Boureau F, Budowski M, Dietemann L, Guillaumat M, Langlade A (2000) Diagnosis and management acute low back pain with or without sciatica. ANAES/Guidelines Department/February 2000

Negrini S, Giovannoni S, Minozzi S, Barneschi G, Bonaiuti D, Bussotti A, et al. (2006) Diagnostic therapeutic flow-charts for low back pain patients: the Italian clinical guidelines. Eura Medicophys 42(2):151–70. http://www.minervamedica.it/. Accessed Feb 2016

Savigny P, Kuntze S, Watson P, Underwood M, Ritchie G, Cotterell M, Hill D, Browne N, Buchanan E, Coffey P, Dixon P, Drummond C, Flanagan M, Greenough C, Griffiths M, Halliday-Bell J, Hettinga D, Vogel S, Walsh D (2009) Low back pain: early management of persistent nonspecific low back pain. National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners/NICE guidelines [CG88], London. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg88/evidence or http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg88/evidence/full-guideline-243685549. Accessed June 2012

New Zealand acute low back pain guide. available on: http://www.acc.co.nz/PRD_EXT_CSMP/groups/external_communications/documents/guide/prd_ctrb112930.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016

Dagenais S, Tricco AC, Haldeman S (2010) Synthesis of recommendations for the assessment and management of low back pain from recent clinical practice guidelines. Spine J 10(6):514–529

Hooten WM, Cohen SP (2015) Evaluation and treatment of low back pain: a clinically focused review for primary care specialists. Mayo Clin Proc 90:1699–1718

American Pain Society (APS). http://americanpainsociety.org/uploads/education/guidelines/evaluation-management-lowback-pain.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016

Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo RA (2009) Imaging strategies for low-back pain:systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 373(9662):463–472

Shekelle P, Eccles PM, Woolf HS (2001) When should clinical guidelines be updated? BMJ 323:155–157

Reinus WR, Strome G, Zwemer FL Jr (1998) Use of lumbosacral spine radiographs in a level II emergency department. AJR Am J Roentgenol 170:443–447

Deyo RA, Diehl AK (1988) Cancer as a cause of back pain: frequency, clinical presentation, and diagnostic strategies. J Gen Intern Med 3:230–238

Underwood M, Buchbinder R (2013) Red flags for back pain. BMJ 347:f7432

Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, York J, Das A, McAuley JH (2009) Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 60(10):3072–3080

Kroenke K (2014) A practical and evidence-based approach to common symptoms: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med 161(8):579–586

Ferguson FC, Morison S, Ryan CG (2015) Physiotherapists’ understanding of red flags for back pain. Musculoskelet Care 13:42–50

Underwood M (2009) Diagnosing acute nonspecific low back pain: time to lower the red flags? Arthritis Rheum 60:2855–2857

Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, Nair RC, McDowell I, Reardon M, Stewart JP, Maloney J (1993) Decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Refinement and prospective validation. JAMA 269(9):1127–1132

Bachmann LM, Kolb E, Koller MT, Steurer J, ter Riet G (2003) Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ 326(7386):417

Roman M, Brown C, Richardson W, Isaacs R, Howes C, Cook C (2010) The development of a clinical decision making algorithm for detection of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture or wedge deformity. J Man Manip Ther 18(1):44–49

Chou R, Qaseem A, Owens DK, Shekelle P (2011) Diagnostic imaging for low back pain advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 154:181–189

Scavone JG, Latshaw RF, Weidner WA (1981) AP and lateral radiographs: an adequate lumbar spine examination. AJR 136:715–717

Scavone JG, Latshaw RF, Rohrer V (1981) Use of lumbar spine films: statistical evaluation at a university teaching hospital. JAMA 246:1105–1108

Waddell G, McIntosh A, Hutchinson A, Feder G, Lewis M (1999) Low Back Pain Evidence Review. Royal College of General Practitioners, London

Van den Hoogen HJ, Koes BW, Van Eijk JT, Bouter LM (1995) On the diagnostic accuracy of history, physical examination, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in diagnosing low back pain in general practice; a criteria based review of the literature. Spine 20:318–327

Gran JT (1985) An epidemiological survey of the signs and symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 4:161–169

Waddell G (ed) (2004) The back pain revolution. Churchill Livingstone, London, pp 10–11

Yu DT, Sieper J, Romain PL, v Tubergen A Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis in adults. UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-and-differentialdiagnosis-of-ankylosing-spondylitis-in-adults. Last updated September 2015. Accessed 21 Feb 2016

Rajesh K, Brent L Spondyloarthropathies. American Family Physicians. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2004/0615/p2853.html. Accessed Feb 2016

Acknowledgments

We thank Stichting Stoffels-Hornsta for their financial support and we thank Prof Antti Malmivaara for the data extraction of the Finnish guideline and Prof Sita Bierma-Zeinstra for the data extraction of the Norwegian guideline. This study is partly funded by a program grant of the Dutch Arthritis Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Verhagen, A.P., Downie, A., Popal, N. et al. Red flags presented in current low back pain guidelines: a review. Eur Spine J 25, 2788–2802 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4684-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4684-0