Abstract

Background

The use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for routine cancer distress screening is endorsed globally as a quality-care standard. However, there is little research on the integration of PROs in “real-world” oncology practices using implementation science methods. The Improving Patient Experience and Health Outcome Collaborative (iPEHOC) intervention was established at multisite disease clinics to facilitate the use of PRO data by clinicians for precision symptom care. The aim of this study was to examine if patients exposed to the intervention differed in their healthcare utilization compared with contemporaneous controls in the same time frame.

Methods

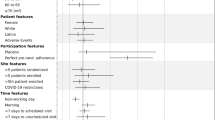

We used a PRE- and DURING-intervention population cohort comparison study design to estimate the effects of the iPEHOC intervention on the difference in difference (DID) for relative rates (RR) for emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, psychosocial oncology (PSO), palliative care visits, and prescription rates for opioids and antidepressants compared with controls.

Results

A small significantly lower Difference in Difference (DID) (− 0.223) in the RR for ED visits was noted for the intervention compared with controls over time (0.947, CI 0.900–0.996); and a DID (− 0.0329) for patients meeting ESAS symptom thresholds (0.927, CI 0.869–0.990). A lower DID in palliative care visits (− 0.0097), psychosocial oncology visits (− 0.0248), antidepressant prescriptions (− 0.0260) and an increase in opioid prescriptions (0.0456) in the exposed population compared with controls was also noted. A similar pattern was shown for ESAS as a secondary exposure variable.

Conclusion

Facilitating uptake of PROs data may impact healthcare utilization but requires examination in larger scale “real-world” trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Holland J, Watson M, Dunn J (2011) The IPOS new international standard of quality Cancer care: integrating the psychosocial domain into routine cancer care. Psycho-Oncology 20:677–680

Alemayehu D, Cappelleri JC (2012) Conceptual and analytic considerations toward the use of patient-reported outcomes in personalized medicine. Am Health Drug Benefits 5(5):310–317

PROMs Background Document, Canadian Institute for Health Information. PROMs Forum Feb 2015. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/proms_background_may21_en-web.pdf

Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ (2013) A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organizations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res 11(13):211

Yang L, Manhas D, Howard A et al (2014) Patient-reported outcome use in oncology: a systematic review of the impact on patient-clinician communication. Support Care Cancer 26:41–60

Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, Harrow A, di Domenico D, Croy S, MacGillivray S (2014) What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 32(14):1480–1501

Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, Scher HI, Kris MG, Hudis C, Schrag D (2017) Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 318:197–198

Denis F, Lethrosne C, Pourel N et al (2017) Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up with routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 109:1460–2105

Stover A, Irwin DE, Chen RC et al (2015) Integrating patient-reported measures into routine cancer care: cancer patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of acceptability and value. EGEMS The Electronic Journal for Electronic Health Data and Methods (Wash DC) 3(1):1169. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1169

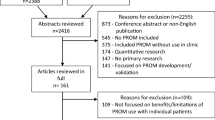

Anachkova M, Donelson S, Ska Licks AM et al (2018) Exploring the implementation of patient-reported outcome measures in cancer care: need for more ‘real-world’ evidence results in the peer reviewed literature. J Patient-Reported Outcomes 2(64):1–21

Howell D, Hack TF, Green E, Fitch M (2014) Cancer distress screening data: translating knowledge into clinical action for a quality response. Palliat Supp Care 12(1):39–51

Mitchell S, Chambers D (2017) Leveraging implementation science to improve cancer care delivery and patient outcomes. JOP 13(8):523–539

Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Flynn R (2005) The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical care: lack of impact or lack of theory? Soc Sci Med 60:833–843

Li M, Macedo L, Crawford S et al (2016) Easier said than done: keys to successful implementation of the Distress Assessment and Response Tool (DART) program. JOP 2(5):e513–e526

Howell D, Molloy S, Wilkinson K, Green E, Orchard K, Wang K, Liberty J (2015) Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: a scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann Oncol 26(9):1846–1858

Santana MJ, Haverman L, Absolom K (2015) Training clinicians in how to use patient-reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice. Qual Life Res 24(7):1701–1718

Pereira J, Green E, Molloy S et al (2014) Population-based standardized symptom screening: Cancer Care Ontario’s Edmonton Symptom Assessment System and performance status initiatives. JOP 10(3):212–214

Seow H, Sussman J, Martelli-Reid L et al (2012) Do high symptom scores trigger clinical actions? An audit after implementing electronic symptom screening. JOP 8(6):e142–e148

Graham I, Logan J, Harrison M, Straus S, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N (2006) Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Heal Prof 26:3–24

Hiatt JM (2006) ADKAR: a model for change in business, government and our community. Prosci Learning Center Publications, Loveland

Gagliardi AR, Berta W, Kothari A, Boyko J, Urquart R (2016) Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implement Sci 17(11):38

Thomson O’Brien MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB et al (2000) Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD003030

Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, Damschroeder L, Schmid AA, Damush TM (2018) Inside help: an integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med 6:1–11

Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McMillan CI, Freeman TR (2014) Patient-centered medicine: transforming the clinical method. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton

Howell D, Keller-Olaman S, Oliver T et al. A pan-Canadian practice guideline: screening, assessment and care of psychosocial distress (depression, anxiety) in adults with cancer. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (Cancer Journey Action Group) and the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology. August 2010. Available at http://www.capo.ca/pdf/ENGLISH_Depression_Anxiety_Guidelines_for_Posting_Sept2011.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2017

Watanbe SM, Nekolaichuk C, Beaumont C et al (2011) A multicenter study comparing to numerical versions of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 41:456–468

Dudgeon D, King S, Howell D, Green E, Gilbert J, Hughes E, Lalonde B, Angus H, Sawka C (2011) Cancer Care Ontario’s experience with implementation of routine physical and psychological symptom distress screening. Psychooncology 21(4):357–364

Gilbert J, Howell D, King S, Sawka C, Hughes E, Angus H, Dudgeon D (2012) Quality improvement in cancer symptom assessment and control: the provincial palliative care integration project (PPCIP). J Pain Symptom Manag 43(4):663–678

Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC (1983) Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain 17:197–210

Okuyama T, Akechi T, Kugaya A, Okamura H, Shima Y, Maruguchi M, Hosaka T, Uchitomi Y (2000) Development and validation of the cancer fatigue scale: a brief, three-dimensional, self-rating scale for assessment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 19(1):5–14

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097

Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams W (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. JGIM 16:606–616

Bultz BD, Groff SL, Fitch M, Blais MC, Howes J, Levy K, Mayer C (2011) Implementing screening for distress, the 6th vital sign: a Canadian strategy for changing practice. Psycho-Oncology 28:463–469

Wright EP, Kiely M, Johnston C, Smith AB, Cull A, Selby PJ (2005) Development and evaluation of an instrument to assess social difficulties in routine oncology practice. Qual Life Res 14:373–386

Selby D, Chakraborty A, Myers J, Saskin R, Mazzotta P, Gill A (2011) High scores on the Edmonton symptom assessment scale identify patients with self-defined high symptom burden. J Palliat Med 14:1309–1316

Oldenmenger WH, de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CC (2013) Cut points on 0-10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symp Manage 45(5):1083–1093

Bagha SM, Macedo A, Jacks LM, Lo C, Zimmermann C, Rodin G, Li M (2013) The utility of the Edmonton symptom assessment system in screening for anxiety and depression. Eur J Cancer Care 22(1):60–69

Iron K, Zagorski BM, Sykora K, Manuel DG (2008) Living and dying in ontario: An opportunity for improved health information. ICES investigative report Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

Discharge Abstracts Database of CIHI (DAD) Canadian Institute for Health Information (2012) Data quality documentation, discharge abstract database — current year information. CIHI, Ottawa, ON http://www.cihi.ca. Accessed on April 2016

Canadian Institute for Health Information: CIHI Data Quality Study of Ontario Emergency Department Visits for Fiscal Year 2007, in Ottawa, Ontario, 2007

Symptom assessment and management Cancer Quality Council of Ontario www.csqi.on.ca/cms/one.aspx?portalId=258922&pageId=272723#.UtXPvvRDsV0

Cancer Activity Level Reporting (ALR) database. Cancer Care Ontario's Data Book - 2016-2017

Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) Database, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care

Barbera LC, Seow H, Husain A, Howell D et al (2011) How often are opioids prescribed for cancer patients reporting pain? Results of a population-based analysis. JCO 29(15):6084

Abadie, A. (2005). Semiparametric difference-in-differences estimators. Rev Econ Stud 72 (1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/0034-6527.0032

Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Howell D et al (2015) Does routine symptom screening with ESAS decrease ED visits in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy? Support Care Cancer 23:3025–3032

Butow P, Price MA, Shaw JM, Turner J, Clayton JM, Grimison P, Rankin N, Kirsten L (2015) Clinical pathway for the screening, assessment and management of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: Australian guidelines. Psychooncology 24:987–1001

Mittman BS (2004) Creating the evidence base for quality improvement Collaboratives. Ann Int Med 140:897–901

Greene J, Hibbard JH (2012) Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 27:520–526

Acknowledgments

The iPEHOC study was funded by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (Toronto, Canada) with additional in-kind funding support from Cancer Care Ontario. This study was conducted with the support of the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) through funding provided by the Government of Ontario. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The work of the entire team of iPEHOC research and project team members and our patient partners is acknowledged.

Disclosures

The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by CCO and CIHI. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions ,and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of CIHI or CCO.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research through funding provided by the Government of Ontario.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Howell, D., Li, M., Sutradhar, R. et al. Integration of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for personalized symptom management in “real-world” oncology practices: a population-based cohort comparison study of impact on healthcare utilization. Support Care Cancer 28, 4933–4942 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05313-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05313-3