Abstract

Background

To date, little research has examined the quality of life and cancer-associated needs of bladder cancer patients. The objective of the current study was to assess the quality of life (QoL), informational needs, and supportive care needs (SCN) in a large sample of muscle invasive (MIBC) and non-muscle invasive (NMIBC) bladder cancer survivors across the treatment trajectory (newly diagnosed and undergoing treatment, post-treatment follow-up, and treatment for advanced/recurrent disease).

Methods

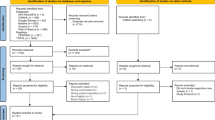

Questionnaires were distributed to a convenience sample of patients registered with Bladder Cancer Canada, the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, or The Ottawa Hospital. Eligibility criteria included being > 18 years of age, English-speaking, and diagnosed with bladder cancer. The questionnaire included an adapted tool to measure informational needs, and validated measures for QoL (Bladder Utility Symptom Scale, BUSS) and SCN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs Measure, CaSUN). QoL scores and unmet needs were calculated and compared between disease groups and cancer trajectory groups.

Results and limitations

Of the 1126 surveys distributed, 586 were completed (response = 52%). Mean age was 67.3 ± 10.2 years, and 401 participants (68.7%) were male. The mean QoL score (BUSS) for the sample was 78.1 ± 17.9 (median 81.7). Respondents with MIBC had significantly lower QoL scores compared to NMIBC. Further, scores differed across the cancer phase groups with the follow-up surveillance group having significantly higher QoL scores compared to the newly diagnosed and advance/recurrent disease groups. The ten most highly ranked informational needs were from the medical, physical, and practical domains. Eighty-eight percent (95% CI 85–91%) of respondents reported at least one SCN, with a median of 12. Over half of the participants (54%, 95% CI 49–59%) had at least one unmet need and 15% had ≥ 10 unmet needs. Newly diagnosed participants had the highest number of unmet needs.

Conclusion

We found that the number of unmet supportive care needs and quality of life differed across cancer trajectory and disease groups. Future efforts should focus on the development and evaluation of tailored resources and programs to address the needs of people diagnosed and treated for BC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bladder cancer (BC) is the second most common genitourinary cancer in North America and accounts for an estimated 4.5% of all new cancer cases worldwide [1]. The largest risk factors for BC are smoking, being male, and age, and the prevalence is expected to significantly increase over the next two decades due to the aging population [2].

The diagnosis and treatment of BC are stressful events associated with numerous supportive care needs (SCN) that continue beyond treatment [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. However, a 2009 survey of BC specialists (n = 43) in North America found that there were limited resources directed to BC survivors including support groups, survivorship programming, community services, and patient navigation/information, and that providers lacked awareness of available resources [12]. Further, there is very little research on the informational needs and SCN of both NMIBC and MIBC survivors; which may in part explain the lack of appropriate and tailored resources directed to them [10, 11]. In addition, the quality of life (QoL) of BC patients has not been well-described despite the complexities of treatment and its chronic nature, and while generic BC-specific measures of QoL have been developed, such as the EORTC QLQ’s, BCI, and FACT-Bl, these instruments have limitations including being restricted to subsets of BC patients, missing important domains for patients, and lacking evidence on psychometric properties [13,14,15,16]. Specific patient-driven global BC QoL scales that include attributes specific to MIBC and NMIBC have only recently been developed [17].

There remains a need for larger, more comprehensive studies that can inform appropriate person-centered care activities for BC patients, including the development and tailoring of appropriate patient education and supportive care resources and services. Consequently, we conducted a large cross-sectional descriptive study to describe the QoL and informational and supportive care needs of NMIBC and MIBC survivors across the cancer care trajectory.

Materials and methods

Participants

BC patients were recruited from the Genitourinary Clinic at Princess Margaret (PM) Cancer Centre, the Urology Clinic at The Ottawa Hospital (TOH), and through Bladder Cancer Canada, a national non-profit organization that seeks to support BC survivors and increase awareness of BC among the general public and medical community. Patients were eligible if they were > 18 years of age, could understand and read English, and had been diagnosed with any stage of NMIBC/MIBC. The study was approved by Research Ethics Boards at the University Health Network and The Ottawa Hospital. Participants were informed that completion of the questionnaire implied consent.

Procedures

Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and The Ottawa Hospital: Patients diagnosed with BC attending clinical appointments were invited to the study and provided the questionnaire package to complete in clinic or return in a pre-paid envelope. Bladder Cancer Canada (BCC): Registered patient members were emailed information regarding the study with a link to the questionnaire that was hosted on FluidSurveys. The four-point survey approach based on Dillman’s Tailored Design Method [18, 19] was used to reduce non-response, which involved sending all registered members an initial e-mail and non-responders up to three follow-up emails. Participants could complete the survey online or by mail.

Study measures

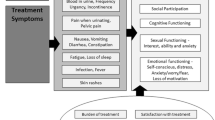

Participants completed a one-time questionnaire that was developed with input from the research team. The questionnaire package was field tested with five randomly selected BC patients attending routine visits to PM. The field test results were reviewed to assess the time it took participants to complete the questionnaire and to identify any issues with completion of the questions. Completion of the survey implied consent. The questionnaire included the following: (1) Demographic and disease and treatment information, which contained questions about age, sex, residence setting, employment status, and comfort with using the internet. Clinical information included type(s) of treatment received, time since diagnosis, stage and type of bladder cancer at diagnosis, and the phase of cancer treatment they identified with, which were categorized into newly diagnosed, follow-up surveillance, and receiving treatment for recurrent or metastatic disease; (2) Quality of life assessed using the Bladder Utility Symptom Scale (BUSS) [10] which is a global health related QoL questionnaire that evaluates generic and BC-specific domains of QoL, including physical changes such as fatigue, bowel, and bladder function. The BUSS has been validated and was developed in consultation with BC patients and experts and included conceptual framework development, item generation and reduction, question design, and pilot testing. The BUSS is self-administered and includes ten questions and a score out of 100 is given to each participant, with higher scores indicating better QoL. In addition, overall health is measured using a 0–100 visual analogue scale [16]; (3) Informational needs assessed using an internally designed, non-validated questionnaire that was developed based on existing literature regarding patient information and supportive care needs [20]. This tool has been used in other cancer populations and can be easily adapted to the population being studied [21,22,23]. For the current study, we included 30 relevant items based on consensus from experts (and removed 12 items deemed not applicable). The measure assesses informational needs in the following domains: medical (5 items), practical (6 items), physical (8 items), social (3 items), emotional (7 items), and spiritual (1 item) [13]. Items are measured on a 5-point Likert scale, and participants rate the importance of each item. Scores for each domain were transformed to a 0–100 scale; and (4) Supportive care needs assessed using the Cancer Survivorship Unmet Needs (CaSUN) tool [24], a 35-item validated tool that assesses met and unmet SCN over the preceding month. For each item, respondents indicate whether the particular need is “not needed/not applicable,” “met,” or “unmet.” The items map to five domains: information (IN) (3 items), comprehensive cancer care (CCC) (6 items), existential survivorship (ES) (14 items), quality of life (QOL) (2 items), and relationships (REL) (3 items). There are also six additional positive change (PC) items, and one open-ended question [24]. The number of total needs (met and unmet) and unmet need are summed for all items (range 0–35) and for each domains.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to provide summary information about the participants and for each outcome measure, and examined for non-normality (kurtosis and skewness). BUSS total scores were not normally distributed and were compared between disease groups (MIBC vs. NMIBC) using Mann-Whiney U test, and between cancer trajectory groups (newly diagnosed and undergoing treatment vs. follow-up surveillance vs. treatment for recurrence or metastatic disease) with Kruskal-Wallis test. The proportion of items rated “important” or “very important” in each informational need domain was alculated with 95% confidence interval (CI), and compared across disease groups and cancer phase groups using chi-squared analyses. Proportion (+ 95% CI) of total and domain-specific SCN (No. answering “Need was fully met” or “Need was not fully met”/total no. responses for that item) were calculated and examined. Proportion of “Unmet needs” was calculated for each item (No. answering “Need was not fully met”/No. who identified need (either met/unmet)). SCN total and domain-specific met or unmet (±SD) needs were non-normally distributed and compared across disease groups and cancer phase groups using Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 with p values of < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Bonferroni correction was made for multiple comparisons.

Results

A total of 586 surveys were completed between November 2014 and April 2016 including n = 204 (204/308, 66%) from PM, n = 129 (129/183, 70%) from TOH, and n = 253 (253/625, 40%) from BCC. The QoL (p = 0.428), informational needs (across domains p = 0.1 to p = 0.95), and SCN scores (met and unmet needs) (p = 0.09) were not statistically different across the three samples (Princess Margaret, Ottawa Hospital and BCC). Consequently, the data was pooled together for analyses.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

The majority of participants were male (68%), born in Canada (68%), had at least post-secondary education (65%), and were very comfortable receiving health information in English (94%). Fifty-seven percent of participants were initially diagnosed with NMIBC, 23% with MIBC, and 18% did not know their diagnosed disease type. At the time of the survey, 13% were newly diagnosed and receiving primary therapy, 66% had completed treatment and were in post-treatment follow-up, and 15% were receiving treatment for recurrent or metastatic disease. Demographic and clinical data are summarized in Table 1.

Quality of life

The mean QoL score (BUSS) for the sample was 78.1 ± 17.9 (median 81.7). Respondents with MIBC had significantly lower scores (median 75) compared to NMIBC (median 85) (U = 9497, p < 0.001). Further, scores differed across the cancer phase groups with the follow-up surveillance group having significantly higher QoL scores (median 83.3) compared to the newly diagnosed (median 72.5) and the recurrent/metastatic groups (median 74.6) (H(2) = 20.71 p < 0.001).

Informational needs

The percentage of items rated “important” or “very important” varied across the domains: medical (95%, 95% CI 94–97%), physical (86%, 95% CI 84–88%), practical (77%, 95% CI 75–80%), emotional (67%, 95% CI 63–70%), social (61%, 95% CI 58–64%), and spiritual (40%, 95% CI 35–44%). The ten most highly ranked informational needs were from the medical [5], physical [3], and practical [2] domains (Table 2).

The MIBC group and the NMIBC group had similar informational needs, with the exception of the practical domain needs, which were ranked higher in the NMIBC group (p = 0.046). Across the cancer phase groups, the informational needs were also similar, with the exception of the practical domain items. They were ranked less important by respondents with recurrent or metastatic disease compared to those with newly diagnosed disease (p = 0.031) or receiving follow-up surveillance (p = 0.035).

Supportive care needs

Eighty-eight percent (95% CI 85–91%) of respondents reported at least one SCN with a median of 12 and a mean of 15 ± 12.2 (out of a total of 35). The most common SCN were in the comprehensive cancer care (CCC) domain with 82% (95% CI 78.8–85.2%) of respondents reporting a need, followed by 65% (95% CI 61.0–68.9%) in the existential survivorship (ES) domain, 55% (95% CI 50.9–59.1%) in the information (IN) domain, 47% (95% CI 42.3–51.2%) in the quality of life (QOL) domain, and 35% (95% CI 31.1–38.9%) in the relationships (REL) domain. The top 10 SCN (met or unmet) are listed in Table 3 (see Supp Table 1 for all SCN).

The median number of unmet needs was 1.0 with a mean of 4.2 ± 6.7. Over half of the participants (54%, 95% CI 49–59%) had at least one unmet need (Fig. 1). The ES domain had the highest proportion of participants who had at least one unmet need (38%, 95% CI 33.5–42.5%), followed by the CCC domain (34%, 95% CI 29.7–37.0%), REL domain (23%, 95% CI 19.1–26.9), QOL domain (18%, 95% CI 14.5–21.5%), and the IN domain (13%, 95% CI 9.9–16.1%). The ten most common unmet SCN are reported in Table 4 (see Supplementary Table 1 for all unmet SCN).

Proportion of participants reporting unmet needs. Proportion of study participants by number of unmet supportive care needs. The number of unmet needs were grouped into ranges of five. Labels represent the proportion of the entire study population that had the corresponding ranges of unmet supportive care needs

The MIBC group had median of 1.0 unmet need (mean 4.6 ± 6.5), and the NMIBC group also had a median of 1.0 unmet need (mean of 4.2 ± 6.8) (U = 13,549.00, p = 0.28). The number of unmet needs differed across the cancer journey groups (H(2) = 17.68, p < 0.001). Newly diagnosed participants had a median of 3.5 unmet needs; participants in post-treatment follow-up had a median of 0.0 unmet needs, and those in the metastatic or recurrent cancer had a median 1.5 unmet needs.

Fourteen percent (82/586) of respondents had ≥ 10 unmet needs with a median of 16.0 unmet SCN (mean 17.4 ± 5.8). This group of patients were more likely to be newly diagnosed with (25% vs. 13%, p = 0.018) and had lower total BUSS score (60.3 ± 21.1) compared to respondents who had < 10 unmet SCN (79.6 ± 14.7, p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive cross-sectional description of the QoL, informational needs, and SCN of BC survivors. It also includes large samples of both MIBC and NMIBC patients at all phases of the cancer trajectory.

QoL was found to be lower in patients with MIBC compared to NMIBC, and in patients who were newly diagnosed or had metastatic or recurrent disease when compared to those who finished treatment and were in long-term follow-up. These findings are not surprising given that more advanced disease requires more complex treatments that may result in a decline in functional health and increased symptom burden along with psychosocial and existential issues related to death and dying [25, 26], and highlight the need for early intervention with palliative programs and services. In addition, the diagnostic and primary treatment phases can be difficult due to acute treatment-related effects [27]. In a recent systematic review of the qualitative evidence on the experience of being diagnosed and treated for bladder cancer, Edmonston et al. describe patient initial shock and fear at diagnosis, subsequent challenges when making treatment decisions including the patient’s struggle to understand treatment options and potential side effects, and the need for support in managing acute side effects of treatment and development of self-management skills [3]. It was encouraging that QoL scores are significantly higher in those who were receiving posttreatment follow-up care, a finding that may suggest that QoL impairments may improve once treatment ends. This finding is supported by qualitative data which describes QoL in BC survivors as initially worse for some patients as they struggle to adapt to a new normal [28] but slowly improves over time as patients begin to feel better and adapt to a “new normal” despite long-term effects of their cancer [29, 30].

In terms of informational needs, we found that the highest-rated domain was the medical domain, which included general knowledge about their cancers, treatment options and side effects, and subsequent post-treatment tests. This result is consistent with findings reported in other cancer patient populations [22, 23]. In a recent qualitative study of MIBC patients, Mohamed et al. found that informational needs of newly diagnosed participants were focused on treatment options and the management of side effects. For postoperative participants, the most important informational needs related to returning to physical and social activities and dealing with worry and fears of cancer recurrence [11]. We found that respondents with MIBC and those who were earlier on in the cancer trajectory placed higher importance on practical information, which includes drug coverage options, home services, and the frequency of hospital visits, maybe due to differences in disease severity and complexity of treatments associated with MIBC, as well as the lack of familiarity with the healthcare system and available resources when one is newly diagnosed.

SCN were also common, with 86% of respondents indicating at least one supportive care need and a median of 12. Most SCN centered on the provision of comprehensive cancer care, such as “feeling like I am managing my health together with the medical team”, and “their care is properly addressed”. Encouragingly, the majority of these needs were met. Approximately half (54%) of the respondents reported ≥ 1 unmet need, and the mean number of unmet needs was lower than the average reported in other cancers [31, 32]. The ES domain, which is primarily psychosocial in nature, addresses needs such as, “concerns of recurrence,” “help with changes in optimism,” and “moving on in life.” It had the highest proportion of unmet needs, with 38% of respondents indicating at least one unmet need in this domain. This finding has been reported in other cancer populations [33, 34]. Patients who were newly diagnosed had higher levels of unmet needs, despite being the group that would see healthcare providers most frequently. The group of respondents with ≥ 10 unmet needs also had a higher proportion of newly diagnosed patients than those who had < 10 unmet needs (25% vs. 13%) and significantly lower quality of life scores. These observations reinforce the need to improve the quality of care for patients early on in their treatment phase, including supporting patients through the decision making process and preparation for treatment and providing open and supportive communication [11, 28, 35, 36].

The findings of this study need to be interpreted in the context of its limitations. This was a cross-sectional study, which does not allow for the examination of cause-effect relationships. In addition, this study was restricted to English-speaking residents in Canada and may not be representative of non-English speaking individuals, or those outside of Canada. We did not address some demographic questions regarding income or caregiver status, which may have had impacts on needs and QoL of the participants. In addition, approximately 2/3 of the study population had a post-secondary education which may be due to the online nature and questionnaire-based nature of the study. This may impact the representation of these findings to the entire BC patient population and potentially result in an underestimation of need. Furthermore, the study cohort may have a larger proportion of younger patients due to the online approach for the BCC population, which can impact the representation of these findings to the entire BC patient population. The BCC group was younger than the PM and OCC cohorts. The use of both online and offline questionnaires may also partially explain the lower response rates seen in the online cohort, as there was no personal interaction and waiting time in the clinic with BCC respondents as there were in the TOH and UHN sites. However, since the informational needs, SCN, and QoL scores did not differ significantly across the three sites, the different response rates likely did not affect our analyses. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insight into the QoL, informational needs, and SCN of BC patients. It also emphasizes the need for the development of targeted educational resources, formalized education pathways, and screening for and addressing SCN, as they are common and significantly impact QoL.

Conclusion

This work provides the initial groundwork to improve person-centered care provided to BC patients. Healthcare professionals play an important role in the provision of patient education and psychosocial support at all phases of treatment, as they are often the patients’ first point of contact. While there are clear benefits in providing appropriate and effective patient education and psychosocial care [37, 38], patients may be reluctant to disclose their SCN with their oncologists. These barriers and gaps impede patients from receiving the required comprehensive care that addresses their needs [39]. These findings highlight the need to develop a standardized approach to the assessment and provision of supportive care that is embedded within care pathways [40]. Future efforts should focus on the development and evaluation of tailored resources and programs to address the needs of people diagnosed and treated for BC.

References

Malats N, Real FX (2015) Epidemiology of bladder cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 29(2):177–189 vii

Burger M, Catto JW, Dalbagni G, Grossman HB, Herr H, Karakiewicz P et al (2013) Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. Eur Urol 63(2):234–241

Porter MP, Wei JT, Penson DF (2005) Quality of life issues in bladder cancer patients following cystectomy and urinary diversion. Urol Clin North Am 32(2):207–216

Thulin H, Kreicbergs U, Wijkstrom H, Steineck G, Henningsohn L (2010) Sleep disturbances decrease self-assessed quality of life in individuals who have undergone cystectomy. J Urol 184(1):198–202

Thulin H, Kreicbergs U, Onelov E, Ahlstrand C, Carringer M, Holmang S et al (2011) Defecation disturbances after cystectomy for urinary bladder cancer. BJU Int 108(2):196–203

Botteman MF, Pashos CL, Hauser RS, Laskin BL, Redaelli A (2003) Quality of life aspects of bladder cancer: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res 12(6):675–688

Shih C, Porter MP (2011) Health-related quality of life after cystectomy and urinary diversion for bladder cancer. Ther Adv Urol 2011:715892

Henningsohn L, Wijkstrom H, Dickman PW, Bergmark K, Steineck G (2001) Distressful symptoms after radical cystectomy with urinary diversion for urinary bladder cancer: a Swedish population-based study. Eur Urol 40(2):151–162

Henningsohn L, Wijkstrom H, Steven K, Pedersen J, Ahlstrand C, Aus G et al (2003) Relative importance of sources of symptom-induced distress in urinary bladder cancer survivors. Eur Urol 43(6):651–662

Mohamed NE, Pisipati S, Lee CT, Goltz HH, Latini DM, Gilbert FS et al (2016) Unmet informational and supportive care needs of patients following cystectomy for bladder cancer based on age, sex, and treatment choices. Urol Oncol 34(12):531 e7- e14

Mohamed NE, Chaoprang Herrera P, Hudson S, Revenson TA, Lee CT, Quale DZ, Zarcadoolas C, Hall SJ, Diefenbach MA (2014) Muscle invasive bladder cancer: examining survivor burden and unmet needs. J Urol 191(1):48–53

Lee CT, Mei M, Ashley J, Breslow G, O'Donnell M, Gilbert S, Lemmy S, Saxton C, Sagalowsky A, Sansgiry S, Latini DM, Bladder Cancer Think Tank., Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network (2012) Patient resources available to bladder cancer patients: a pilot study of healthcare providers. Urology 79(1):172–177

EORTC Quality of Life Department. Bladder Cancer: EORTC QLQ-NMIBC24, EORTC QLQ-BLM30 Ave. E. Mounier 83, B.11, 1200 Brussels, BELGIUM, [Available from: http://groups.eortc.be/qol/bladder-cancer-eortc-qlq-nmibc24-eortc-qlq-blm30

Mansson A, Davidsson T, Hunt S, Mansson W (2002) The quality of life in men after radical cystectomy with a continent cutaneous diversion or orthotopic bladder substitution: is there a difference? BJU Int 90(4):386–390

Guren MG, Wiig JN, Dueland S, Tveit KM, Fossa SD, Waehre H et al (2001) Quality of life in patients with urinary diversion after operation for locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 27(7):645–651

Perlis N (2013) Developing the bladder utility symptom scale: a multiattribute health state classification system for bladder cancer. UofT, Toronto

Perlis N, Krahn MD, Boehme KE, Alibhai SMH, Jamal M, Finelli A, Sridhar SS, Chung P, Gandhi R, Jones J, Tomlinson G, Bremner KE, Kulkarni G (2018) The bladder utility symptom scale: a novel patient reported outcome instrument for bladder Cancer. J Urol 200(2):283–291

Dillman DA (1999) Mail and Internet surveys - the tailored design method. Wiley & Sons, New York

Dillman DA (2007) Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method 2007 update with new internet, visual, and mixed-mode guide. Hoboken, New Jersey, John Wiley & Sons, Inc

Steele R, Fitch MI (2008) Supportive care needs of women with gynecologic cancer. Cancer Nurs 31(4):284–291

Papadakos J, McQuestion M, Gokhale A, Damji A, Trang A, Abdelmutti N, Ringash J (2018) Informational needs of head and neck cancer patients. J Cancer Educ 33(4):847–856

Papadakos J, Urowitz S, Olmstead C, Jusko Friedman A, Zhu J, Catton P (2015) Informational needs of gastrointestinal oncology patients. Health Expect 18(6):3088–3098

Papadakos J, Bussiere-Cote S, Abdelmutti N, Catton P, Friedman AJ, Massey C et al (2012) Informational needs of gynecologic cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol 124(3):452–457

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Pendlebury S, Hobbs KM, Lo SK, Wain G (2007) The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: the CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ unmet needs measure). Psychooncology 16(9):796–804

Tang ST, Chang WC, Chen JS, Su PJ, Hsieh CH, Chou WC (2014) Trajectory and predictors of quality of life during the dying process: roles of perceived sense of burden to others and posttraumatic growth. Support Care Cancer 22(11):2957–2964

Mohamed NE, Gilbert F, Lee CT, Sfakianos J, Knauer C, Mehrazin R, Badr H, Wittmann D, Downs T, Berry D, Given B, Wiklund P, Steineck G (2016) Pursuing quality in the application of bladder cancer quality of life research. Bladder Cancer 2(2):139–149

Mazzotti E, Antonini Cappellini GC, Buconovo S, Morese R, Scoppola A, Sebastiani C, Marchetti P (2012) Treatment-related side effects and quality of life in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 20(10):2553–2557

Edmondson AJ, Birtwistle JC, Catto JWF, Twiddy M (2017) The patients’ experience of a bladder cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. J Cancer Surviv 11(4):453–461

Cerruto MA, D'Elia C, Cacciamani G, De Marchi D, Siracusano S, Iafrate M et al (2014) Behavioural profile and human adaptation of survivors after radical cystectomy and ileal conduit. Health Qual Life Outcomes 12:46

Foley KL, Farmer DF, Petronis VM, Smith RG, McGraw S, Smith K, Carver CS, Avis N (2006) A qualitative exploration of the cancer experience among long-term survivors: comparisons by cancer type, ethnicity, gender, and age. Psychooncology 15(3):248–258

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt G, Pendlebury S, Hobbs K, Wain G (2006) Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2-10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 15(5):515–523

Giuliani M, McQuestion M, Jones J, Papadakos J, Le LW, Alkazaz N et al (2016) Prevalence and nature of survivorship needs in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 38(7):1097–1103

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, Hunt GE, Stenlake A, Hobbs KM, Brand A, Wain G (2007) Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol 104:381–389

Soothill K, Morris SM, Harman J, Francis B, Thomas C, McIllmurray MB (2001) The significant unmet needs of cancer patients: probing psychosocial concerns. Support Care Cancer 9(8):597–605

Berry DL, Nayak M, Halpenny B, Harrington S, Loughlin KR, Chang P, Rosenberg JE, Kibel AS (2015) Treatment decision making in patients with bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer 1(2):151–158

Skea ZC, Maclennan SJ, Entwistle VA, N'Dow J (2014) Communicating good care: a qualitative study of what people with urological cancer value in interactions with health care providers. Eur J Oncol Nurs 18(1):35–40

Gold DT, McClung B (2006) Approaches to patient education: emphasizing the long-term value of compliance and persistence. Am J Med 119(4 Suppl 1):S32–S37

Devine EC, Westlake SK (1995) The effects of psychoeducational care provided to adults with cancer: meta-analysis of 116 studies. Oncol Nurs Forum 22(9):1369–1381

Jacobsen PB, Wagner LI (2012) A new quality standard: the integration of psychosocial care into routine cancer care. J Clin Oncol : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 30(11):1154–1159

Botti M, Endacott R, Watts R, Cairns J, Lewis K, Kenny A (2006) Barriers in providing psychosocial support for patients with cancer. Cancer Nurs 29(4):309–316

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

REB approval was obtained.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data

The corresponding author has full control of all primary data and agrees to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, J., Kulkarni, G.S., Morash, R. et al. Assessment of quality of life, information, and supportive care needs in patients with muscle and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer across the illness trajectory. Support Care Cancer 27, 3877–3885 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-4649-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-4649-z