Abstract

Purpose

The course of quality of life after diagnosis of gynecologic cancer is not well understood. We aimed to identify subgroups of gynecologic cancer patients with distinct trajectories of quality of life outcomes in the 18-month period after diagnosis. We also aimed to determine whether these subgroups could be distinguished by predictors derived from Social-Cognitive Processing Theory.

Methods

Gynecologic cancer patients randomized to usual care as part of a psychological intervention trial (NCT01951807) reported on depressed mood, quality of life, and physical impairment soon after diagnosis and at five additional assessments ending 18 months after baseline. Clinical, demographic, and psychosocial predictors were assessed at baseline, and additional clinical factors were assessed between 6 and 18 months after baseline.

Results

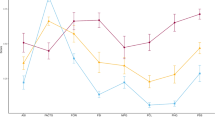

A two-group growth mixture model provided the best and most interpretable fit to the data for all three outcomes. One class revealed subclinical and improving scores for mood, quality of life, and physical function across 18 months. A second class represented approximately 12 % of patients with persisting depression, diminished quality of life, and greater physical disability. Membership of this high-risk subgroup was associated with holding back concerns, more intrusive thoughts, and use of pain medications at the baseline assessment (ps < .05).

Conclusions

Trajectories of quality of life outcomes were identified in the 18-month period after diagnosis of gynecologic cancer. Potentially modifiable psychosocial risk factors were identified that can have implications for preventing quality of life disruptions and treating impaired quality of life in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Greimel E, Thiel I, Peintinger F, Cegnar I, Pongratz E (2002) Prospective assessment of quality of life of female cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 85:140–147

Lutgendorf SK, Anderson B, Ullrich P, Johnsen EL, Buller RE, Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Ritchie J (2002) Quality of life and mood in women with gynecologic cancer. Cancer 94:131–140

Roland KB, Rodriguez JL, Patterson JR, Trivers KF (2013) A literature review of the social and psychological needs of ovarian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 22:2408–2418

Creamer M, Burgess P, Pattison P (1990) Cognitive processing in post-trauma reactions: some preliminary findings. Psychol Med 20:597–604

Manne S, Ostroff JS, Winkel G (2007) Social-cognitive processes as moderators of a couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychol 26:735

Manne SL, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Grana G, Fox K (2005) Partner unsupportive responses, avoidant coping, and distress among women with early stage breast cancer: patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychol 24:635

Dakof GA, Taylor SE (1990) Victims' perceptions of social support: what is helpful from whom? J Pers Soc Psychol 58:80

Koopman C, Hermanson K, Diamond S, Angell K, Spiegel D (1998) Social support, life stress, pain and emotional adjustment to advanced breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 7:101–111

Norton TR, Manne SL, Rubin S, Hernandez E, Carlson J, Bergman C, Rosenblum N (2005) Ovarian cancer patients' psychological distress: the role of physical impairment, perceived unsupportive family and friend behaviors, perceived control, and self-esteem. Health Psychol 24:143

Manne S, Badr H (2008) Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer 112:2541–2555

Badr H, Carmack CL, Kashy DA, Cristofanilli M, Revenson TA (2010) Dyadic coping in metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychol 29:169

Manne S, Badr H, Zaider T, Nelson C, Kissane D (2010) Cancer-related communication, relationship intimacy, and psychological distress among couples coping with localized prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv 4:74–85

Lepore SJ (2001) A social–cognitive processing model of emotional adjustment to cancer. In: Baum A, Andersen B (eds) Psychological interventions for cancer. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., pp. 99–116

Figueiredo MI, Fries E, Ingram KM (2004) The role of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 13:96–105

Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Hurwitz H, Faber M (2005) Disclosure between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their spouses. Psycho-Oncology 14:1030–1042

Myers SB, Manne SL, Kissane DW, Ozga M, Kashy DA, Rubin S, Heckman C, Rosenblum N, Morgan M, Graff JJ (2013) Social–cognitive processes associated with fear of recurrence among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers. Gynecol Oncol 128:120–127

Lutgendorf SK, Anderson B, Rothrock N, Buller RE, Sood AK, Sorosky JI (2000) Quality of life and mood in women receiving extensive chemotherapy for gynecologic cancer. Cancer 89:1402–1411

Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Rothrock NE, Anderson B (2006) Coping and quality of life among women extensively treated for gynecologic cancer. Psycho-Oncology 15:132–142

Donovan KA, Gonzalez BD, Small BJ, Andrykowski MA, Jacobsen PB (2013) Depressive symptom trajectories during and after adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Ann Behav Med 47:292–302

Zhou Y, Irwin ML, Ferrucci LM, McCorkle R, Ercolano EA, Li F, Stein K, Cartmel B (2016) Health-related quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors: results from the American Cancer Society's study of cancer survivors—I. Gynecol Oncol 141:543–549

Zeng Y, Cheng A, Liu X, Feuerstein M (2016) Symptom profiles, work productivity and quality of life among Chinese female cancer survivors. Gynecology & Obstetrics 6:2161

Mirabeau-Beale KL, Kornblith AB, Penson RT, Lee H, Goodman A, Campos SM, Duska L, Pereira L, Bryan J, Matulonis UA (2009) Comparison of the quality of life of early and advanced stage ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol 114:353–359

Teng FF, Kalloger SE, Brotto L, McAlpine JN (2014) Determinants of quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors: a pilot study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 36:708–715

Ahmed-Lecheheb D, Joly F (2016) Ovarian cancer survivors’ quality of life: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 10:1–13

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J (1961) An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 4:561

Avis NE, Levine BJ, Case LD, Naftalis EZ, Van Zee KJ (2015) Trajectories of depressive symptoms following breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 24:1789–1795

Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG (1988) Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 8:77–100

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (2003) Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 41:582–592

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, Brannon J et al (1993) The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11:570–579

Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, Scott C, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T (2012) Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 366:1382–1392

Stafford L, Foley E, Judd F, Gibson P, Kiropoulos L, Couper J (2013) Mindfulness-based cognitive group therapy for women with breast and gynecologic cancer: a pilot study to determine effectiveness and feasibility. Support Care Cancer 21:3009–3019

McCarroll M, Armbruster S, Frasure H, Gothard M, Gil K, Kavanagh M, Waggoner S, von Gruenigen V (2014) Self-efficacy, quality of life, and weight loss in overweight/obese endometrial cancer survivors (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol 132:397–402

Yost KJ, Eton DT (2005) Combining distribution-and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally important differences the FACIT experience. Evaluation & the Health Professions 28:172–191

Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J, Webster K, Cella D (2005) General population and cancer patient norms for the functional assessment of cancer therapy-general (FACT-G). Evaluation & the Health Professions 28:192–211

Ganz P, Schag C, Lee J, Sim M-S (1992) The CARES: a generic measure of health-related quality of life for patients with cancer. Qual Life Res 1:19–29

Hawighorst-Knapstein S, Schönefußrs G, Hoffmann SO, Knapstein PG (1997) Pelvic exenteration: effects of surgery on quality of life and body image—a prospective longitudinal study. Gynecol Oncol 66:495–500

Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M, Clark MA (2014) Coping and benefit finding among long-term breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. Women & Therapy 37:222–241

Manne S, Schnoll R (2001) Measuring supportive and unsupportive responses during cancer treatment: a factor analytic assessment of the partner responses to cancer inventory. J Behav Med 24:297–321

Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, Yount SE, McGregor BA, Arena PL, Harris SD (2001) Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol 20:20

Tomich PL, Helgeson VS (2004) Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychol 23:16

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W (1979) Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 41:209–218

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK (1989) Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 56:267

Ram N, Grimm KJ (2009) Methods and measures: growth mixture modeling: a method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. Int J Behav Dev 33:565–576

Manne SL, Norton TR, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G (2007) Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: the moderating role of relationship satisfaction. J Fam Psychol 21:380

Harding S, Sanipour F, Moss T (2014) Existence of benefit finding and posttraumatic growth in people treated for head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Peer J 2:e256

Carver CS, Antoni MH (2004) Finding benefit in breast cancer during the year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after diagnosis. Health Psychol 23:595

Wang Y, Zhu X, Yi J, Tang L, He J, Chen G, Li L, Yang Y (2015) Benefit finding predicts depressive and anxious symptoms in women with breast cancer. Qual Life Res 24:2681–2688

Costa RV, Pakenham KI (2012) Associations between benefit finding and adjustment outcomes in thyroid cancer. Psycho-Oncology 21:737–744

Portenoy RK (2011) Treatment of cancer pain. Lancet 377:2236–2247

Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, Arndt V (2010) Quality of life among long-term (⩾ 5 years) colorectal cancer survivors—systematic review. Eur J Cancer 46:2879–2888

Tickoo RS, Key RG, Breitbart WS (2015) Cancer-related pain. In: Holland JC, Breitbart WS, Butow PN, Jacobsen PB, Loscalzo MJ, McCorkle R (eds) Psycho-oncology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 171–198

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Sara Frederick, Tina Gadja, Shira Hichenberg, and Kristen Sorice for study management, Joanna Crincoli, Katie Darabos, Lauren Faust, Rebecca Henderson, Sloan Harrison, Travis Logan, Kellie McWilliams, Marie Plaisme, Danielle Ryan, Arielle Schwerd, Kaitlyn Smith, Nicole Teitelbaum, and Amanda Viner for collection of study data. We thank the oncologists and nurses at all five cancer centers for allowing access to patients. Finally, we thank the study participants and therapists for their time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by grants R01CA85566 (PI: Manne) and R01CA185623-S1 (PI: Bandera) from the National Cancer Institute.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gonzalez, B.D., Manne, S.L., Stapleton, J. et al. Quality of life trajectories after diagnosis of gynecologic cancer: a theoretically based approach. Support Care Cancer 25, 589–598 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3443-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3443-4