Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the study was to assess experiences with sexual dysfunctions, psychosexual support, and psychosexual healthcare needs among cervical cancer survivors (CCSs) and their partners.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with CCSs (n = 30) and their partners (n = 12).

Results

Many participants experienced one or more sexual dysfunctions often causing feelings of distress. Most participants reported having been asked about their sexual functioning, although attention for sexual functioning was often limited and medically oriented. Considering sexuality a taboo topic hampered some participants to seek help. Many participants desired information about treatment consequences for sexual functioning, practical advice on dealing with dysfunctions, and reassurance that it is common to experience sexual dysfunction. A website was generally considered a useful and accessible first resource for information about sexual functioning after cancer.

Conclusions

Sexual dysfunctions are often distressing. Many patients and partners experience psychosexual healthcare needs, but the provided information and care is generally limited. Psychosexual support should go beyond physical sexual functioning and should take aspects such as sexual distress, relationship satisfaction, and the partner perspective into account. Additionally, offering more practical and reassuring information about sexuality after cervical cancer would be valuable for both CCSs and their partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attention to cancer and treatment side effects is increasingly becoming part of survivorship care [1]. Cervical cancer (CC) has a yearly incidence rate of around 700 in the Netherlands, and a 10-year survival of 60 % [2]. Sexual dysfunctions (e.g., vaginal dryness, pain at intercourse, decreased interest in sex) are an important treatment side effect, and studies show that 23 to 70 % of the cervical cancer survivors (CCSs) report problems with their sexual functioning [3–9]. Distress, such as embarrassment, guilt, or sadness, is a common consequence of sexual dysfunctions [10, 11].

Relatively little is known about how sexual dysfunctions affect quality of life and relationship satisfaction. Additionally, few studies have focused on how patients perceive existing psychosexual support and which needs they have. From quantitative studies, it is known that many more gynecological cancer survivors (GCSs) report psychosexual healthcare needs compared to the number of women who actually seek help [8, 12]. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that only one third of the CCSs with a need for psychosexual support had actually initiated a conversation with a professional [13]. Interviews with women treated for ovarian cancer demonstrated that they hardly received psychosexual support from their healthcare providers [14]. Not yet well established are differences in psychosexual support needs between women experiencing sexual distress versus those who do not. Finally, more insight is needed into the partner perspective. Quantitative studies into the impact of cancer on partner’s sexual satisfaction show conflicting results [15–19], and few qualitative studies into sexuality after GC have incorporated the partner perspective [20, 21].

This qualitative study aimed to build upon the existing research by assessing CCSs’ desired sexual health-related services while distinguishing between women who are sexually distressed and women who are not and by incorporating both the survivor and the partner perspective. The research questions were the following: (1) How do CCSs and partners experience sexual dysfunctions that have occurred as a result of the treatment?; (2) How do CCSs and partners experience the information and care provision with respect to sexual functioning after CC?; and (3) What are survivors’ and partners psychosexual healthcare needs, how do these relate to sexual distress, and what are their attitudes towards different modes of delivery of interventions targeting sexual dysfunctions?

Methods

Participants and recruitment procedures

A purposive sampling strategy was used aiming to recruit about 30 participants from a sample of CCSs who had expressed their willingness to participate in future studies during their participation in a multicenter cross-sectional questionnaire study [13]. Sampling took place until no new relevant themes emerged (data saturation).

A random sample of 54 eligible women (treated at the Leiden University Medical Center or the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam in the past 1 to 12 years who had indicated to have at least once experienced a need for information or help) was invited for the study. Women who did not respond to the invitation were telephoned 2 weeks later. Out of all CCSs who were invited for the study, 30 (56 %) agreed to be interviewed (referred to as “participants”). The most frequently mentioned reasons for not participating were that the topic was too intimate or intimidating. All participants with a partner were requested to ask their partner to participate. Out of the 26 participants with a partner, 12 partners (33 %) participated (referred to as “partners”). The LUMC Medical Ethical Committee approved the study.

Data collection and interview topics

The face-to-face interviews were conducted by WV and RB either in a private room at the hospital or at the participant’s home. The interviews took approximately 65 min for the participants and 56 min for the partners. We chose to conduct the interviews with the participants and their partners separately, to facilitate participants to speak freely about their individual experiences. All interviews were audio taped and transcribed verbatim. Topics that were discussed were the impact of the cancer treatment on sexual functioning, the information and care provision, psychosexual healthcare needs, and attitudes towards different modes of information and intervention delivery (see Table 1). For the topics related to the impact of the treatment on sexual functioning and received information and support, a Life History Calendar (LHC) method was used. A LHC is a matrix with time units horizontally (i.e., 1 year before diagnosis; diagnosis; treatment; 3, 6, and 12 months after diagnosis; until 5 years after diagnosis) and domain cues (i.e., work, relational status, important life events, holidays, disease and treatment, sexual functioning, received information and care) listed vertically. The LHC is a reliable method for collecting retrospective information [22].

Based on the interviews with the first 19 participants (and 7 partners), the development of a psychoeducational website about sexuality after CC seemed an acceptable intervention to the participants. To further study the feasibility of this specific intervention, it was decided for the remaining interviews to ask participants to comment more extensively on the website instead of on each intervention delivery mode. Lastly, demographic characteristics and treatment information were retrieved from previously collected data and medical records.

Data analyses

The data were coded and analyzed with NVivo [23] using the framework approach. This approach allowed us to make use of both already existing knowledge about this topic and insights that emerged directly from the data [24]. After familiarization with the data, WV made a first version of a coding scheme that was based on the interview guide. RB and WV independently coded a random sample of three interviews and compared their coding. New codes that emerged from the data were discussed and, if deemed of added value, added to the codebook. Any discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion. WV and RB repeated this procedure five times until 15 interviews were coded. WV continued to code the remaining interviews while RB independently coded every third interview. To promote reliability, WV and RB discussed these double-coded interviews to cross-check and—if needed—complement the coding [25].

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 2 gives an overview of the participant and partner characteristics. The average age of the 30 participants was 47 years (SD = 8; range, 34–68). Twenty-five participants had a male and one had a female partner. The average time since treatment was 6 years (SD = 3). The mean age of the 12 participating partners was 46 years (SD = 8; range, 31–54). Eleven of the partners were male and one was female (all partners will however be addressed as “he”). A synthesis of the findings will be given structured around the research questions with Table 3 providing an overview of exemplary quotes.

Experiences with respect to sexual dysfunctions

Factors related to sexuality after CC

Almost half of the participants stated having become infertile by their treatment. For many, this had led to feelings of grief and had affected their feelings of womanhood (quote 1). About two thirds of the participants stated having incontinence or bowel problems. For some women, sex had become less spontaneous as a consequence of worrying about urine leakage during sexual activity (quote 2). Almost half of the women reported having lymphedema, which caused swelling of the legs and sometimes forced them to wear compression stockings. Two thirds of the participants said that surgery and/or RT had caused physical changes to the vagina (e.g., shortening or narrowing). For about half of the participants, their bodily changes had led to a negative body image or feelings of insecurity (quote 3). Although it was not a part of the interview guide, four participants mentioned the human papillomavirus (HPV) as a cause of their disease or as a reason to be fearful resuming sexual activity.

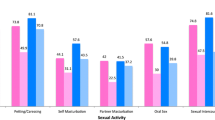

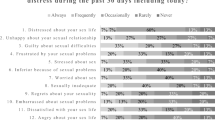

Sexual functioning and distress

More than half of the participants experienced a decreased interest in sex since their treatment (quote 4). Some of them also explained their loss of libido as a result of relationship duration, age, or sexuality having become less important. Seven participants had a new partner since their treatment, which had often evoked a renewed interest in sexual contact. Some partners of women with a decreased interest in sex felt an unchanged desire whereas others had noticed that their libido had decreased as well (quote 5).

About two thirds of the participants mentioned that their vagina had become dry since their treatment. More than half of the participants stated having (had) pain during intercourse or mentioned experiencing an anxiety of pain or penetration irrespective of actual experiences of pain. The (anxiety for) pain made participants avoid sexual intercourse (quote 6). Many partners said that they were more inhibited because they feared hurting their spouse or noticed her (anxiety for) pain (quote 7).

About half of the participants expressed an ability to cope with sexual dysfunctions or considered their sexual functioning as matching with their age or relationship duration. This did not prevent half of the participants from (also) expressing feelings of sexual distress. Some participants had a sense of loss because their sexual functioning was impaired by the cancer treatment. Other participants indicated experiencing feelings of guilt towards their partners because of their decreased interest in sex. Based on the expressed feelings of distress, 13 participants could be qualified as sexually distressed (quote 8). For two of the three single participants, their history of cancer was a barrier to start a new relationship (quote 9).

Six of the seven partners, who were already in a relationship before the onset of the disease, reported some degree of problems in their sexual relationship. For all, this (currently or previously) induced negative emotions, such as experiencing a distance from their spouse or a sense of loneliness in the sexual relationship (quote 10). One man mentioned that before treatment, sexuality could serve as a means to reduce tension that was not available anymore. None of the partners who started their relationship after the treatment experienced sexual problems with their spouse.

Relationship functioning and communication about sexuality

For about half of the participants, the cancer (treatment) or the sexual dysfunction had negatively affected their previous or current (sexual) relationship (quote 11). Some participants stated talking openly about sexuality with their partner and/or that he was sensitive to their sexual needs and limitations (quote 12). Other participants experienced communication difficulties. According to some of them, their partner avoided sexual contact and/or seemed to have lost his sexual interest. In contrast, some others felt pressured by their partner being sexually active or were aware that their partner had difficulties accepting her sexual limitations. Partners generally felt that they communicated openly about sexual issues with their spouses. When discussing how they coped with their partner’s sexual dysfunction, some wanted to leave the initiative for sexual contact to her. One partner however said that he was afraid that if he would do that, he would end up having no sexual contact at all (quote 13).

Experiences with information and care provision

As a result of the time interval between the cancer diagnosis and the interview, almost half of the participants acknowledged having difficulties remembering the content of the information about sexuality that was provided. There were also some participants who did not recall having received any information at all. Half of the participants said that they were not focused on their sexual functioning during treatment and recovery (quote 14). Nevertheless, they appreciated having received information about it. With respect to the time window when psychosexual support was desired most, about half of the participants with whom the topic was discussed said that this was the case between 6 and 12 months after treatment.

About one third remembered having received information about the impact of the treatment on sexual functioning. Specific pieces of information that were mentioned were for instance possible physical changes of the vagina, the importance of keeping the vagina accessible, and wound care after treatment. Some participants were not satisfied with the received information, considering it contradictory or incomplete, communicated in a too technical or upfront manner, or not tailored to their needs.

More than half of the participants said that during follow-up, their healthcare provider (mostly the gynecologist) asked them about sexuality, although in the majority of the cases, this was only a brief question with a focus on physical aspects (quote 15). About one third of the participants had either been referred to or had initiated a consultation with a psychologist or sexologist. Six participants felt that their healthcare provider was accessible if they had sexual concerns. Six participants (three of which could be qualified as sexually distressed) indicated having received none or very little professional help for sexual concerns.

Two participants complained that the healthcare provider had insufficiently involved their partner in the information and care provision. When discussing this topic with the partner, two thirds said having been involved. One partner however added that the professional had a too feminine focus on sexuality.

Healthcare needs and attitudes towards modes of intervention delivery

Needs

When asking participants and partners about their psychosexual support needs, they most frequently mentioned a need for information (about consequences of the treatment, vaginal changes, etcetera), followed by a need for receiving practical advice about coping with (their spouse’s) sexual dysfunctions (quote 16). Distressed participants more often expressed a need for practical advices, being reassured that it was common to experience sexual complaints (quote 17), talking more extensively with a professional about sexual concerns (quote 15), and healthcare providers taking more initiative addressing sexual matters. Participants who were not distressed more often reported a need for general information and a more optimistic approach, for instance by communicating that sexual dysfunctions can improve over time.

Barriers to seek professional help

About one third of the participants indicated not experiencing any barriers to seek help or to consider these barriers as less important than the benefits of seeking help. Other participants were reluctant to seek help because they felt that they ought to solve sexual concerns on their own or considered it a taboo to talk about sexual dysfunctions (quote 18). Some participants stated that (a combination of) time, transportation, and costs were practical barriers to seek professional help.

According to the large majority of the participants, partners should be involved so as to provide them with information, teach them how to support their spouse in case of sexual concerns, or address a possible need for support on their side. One participant was more skeptical about partner involvement, because she believed that it could be more difficult discussing sexual concerns in the presence of the partner (quote 19). Generally, partners were in favor of being involved in the information and care provision and would like receiving (practical) advice about communicating about sexual dysfunction and supporting their spouse.

Attitudes towards delivery mode of information and care

About half of the participants had positive attitudes towards written information. Advantages according to the participants were that it was practical to have a written overview and that it prevented them from a confrontation with an overload of (negative) information (quote 20).

Two thirds of the participants and more than half of the partners mentioned positive attributes of a website (with or without tailored advice), for instance that it was an easily accessible and practical source of information. Websites were particularly considered useful as a first resource in the case of sexual concerns. For more complex problems, face-to-face contact was considered more desirable (quote 21). Three partners stressed that the website should originate from a reliable source (e.g., the government or a hospital) and that doctors should refer to the site. Participants who were not sexually distressed were more likely to consider a website a suitable source of practical information. Sexually distressed participants on the other hand more often stated that a website provided information that was too general and therefore not sufficiently helpful. Many participants had positive attitudes towards websites offering tailored advice.

Participants’ attitudes towards (online) support groups varied. Half of the women were reluctant to be confronted with other women’s (negative) narratives. On the other hand, about one third of the participants were (also) interested in hearing possibly informative and useful patient narratives from other women. About one third of the participants thought that information from a professional would be more useful than that from peers or stressed the importance of a content manager checking the accuracy of the information provided. Partners were not interested in narratives from other CCSs or their partners (quote 22).

Since gynecologists were generally the primary care provider during treatment and follow-up, participants considered them specialized, familiar, and hence the obvious professionals to consult for sexual concerns (quote 23). A few participants thought that gynecologists were not sufficiently skilled to provide support in the case of complex and psychological sexual dysfunctions. The most frequently mentioned advantage of seeking help from sexologists was that they were specialized in this matter and could provide support with relational matters (quote 24). Some distressed participants were reluctant to seek help from a sexologist and considered it too confronting; participants who were not distressed did not mention this. Lastly, a few participants mentioned practical barriers of going to a sexologist (having to make a separate appointment, time, transportation, costs). The most frequently mentioned advantages of contacting a nurse or general practitioner for psychosexual support was that they were considered accessible and empathetic. On the other hand, participants questioned if they were sufficiently knowledgeable about sexuality (quote 25).

Discussion

A decreased interest in sex and (fear of) pain were experienced by more than half of the participants. For some participants and partners, pain during intercourse lead to avoidance of sexual activity or feeling inhibited during intercourse. Furthermore, about half of the women and partners reported feelings of sexual distress such as guilt, grief, or feeling lonely in the sexual relationship. Interestingly, much less sexual distress was observed in couples that had started their relation more recently. A study among healthy participants demonstrated that women’s sexual desire was negatively associated with relationship duration [26]. This, and the results of the present study, suggests that the impact of sexual dysfunctions on sexual distress and sexual satisfaction is not only related to physical sexual dysfunction.

Most participants reported having been asked about their sexual functioning or felt that, if needed, healthcare professionals were accessible. This was generally appreciated. Participants considered professionals’ attention for sexual functioning often concise and medically oriented, which has also been demonstrated in other studies [27].

In line with other studies [14, 27–29], receiving information and practical advices were the most widely supported psychosexual support needs of participants and partners. Furthermore, both participants and partners generally thought that it was valuable to involve partners.

Many participants and partners considered a website a useful and accessible first resource for information about sexual functioning after cancer. In case of sexual distress and more complex or severe sexual concerns, participants preferred face-to-face contact with a professional. Attitudes towards online support groups varied from an interest in patient narratives to concerns about unreliable information or a confrontation with negative stories. With respect to face-to-face contact, gynecologists were generally perceived as the primary professional to contact in case of sexual concerns. Sexologists were perceived to be suitable for more complex problems, whereas nurses and general practitioners were more specifically appreciated because of their empathy and accessibility.

A limitation that is worth considering is that CCSs and partners being relatively at ease talking about sexuality or having more pronounced experiences with or opinions about the provision of psychosexual support were more likely to have participated in this study. Furthermore, a general difficulty with needs assessments is that people do not always have very specific ideas about their needs. Former Apple CEO Steve Jobs described this as follows: “It’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them” [30]. During the interviews, we noticed that participants’ narratives were more vivid and flowing when they talked about their experiences with sexual dysfunctions and received psychosexual support than when discussing their attitudes towards hypothetical interventions. Nevertheless, we do believe that asking survivors and their partners about their ideas with respect to future psychosexual support services is valuable because it gives a clear impression of which interventions are acceptable and which are not, and what possible obstacles should be kept in mind.

All in all, the lives and relationships of many CCSs and their partners are negatively affected by sexual dysfunctions. Psychosexual support should go beyond physical sexual functioning and should take aspects such as sexual distress, relationship satisfaction, and the partner perspective into account. Additionally, offering more practical and reassuring information about sexuality and relationship consequences after cervical cancer would be valuable for both CCSs and their partners.

Kindly note that we confirm all personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

References

Salani R (2013) Survivorship planning in gynecologic cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 130:389–397. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.022

Cijfers over kanker

Abbott-Anderson K, Kwekkeboom KL (2012) A systematic review of sexual concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol 124:477–489. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.030

Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G (1999) Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 340:1383–1389. doi:10.1056/NEJM199905063401802

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J (2011) Sexuality after gynaecological cancer: a review of the material, intrapsychic, and discursive aspects of treatment on women's sexual-wellbeing. Maturitas 70:42–57. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.06.013

Jensen PT et al. (2004) Early-stage cervical carcinoma, radical hysterectomy, and sexual function. A longitudinal study. Cancer 100:97–106. doi:10.1002/cncr.11877

Lammerink EA, de Bock GH, Pras E, Reyners AK, Mourits MJ (2012) Sexual functioning of cervical cancer survivors: a review with a female perspective. Maturitas 72:296–304. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.05.006

Lindau ST, Gavrilova N, Anderson D (2007) Sexual morbidity in very long term survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: a comparison to national norms. Gynecol Oncol 106:413–418. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.017

Pieterse QD et al. (2006) An observational longitudinal study to evaluate miction, defecation, and sexual function after radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 16:1119–1129. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00461.x

Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G (2002) Patient-rating of distressful symptoms after treatment for early cervical cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81:443–450

Park SY et al. (2007) Quality of life and sexual problems in disease-free survivors of cervical cancer compared with the general population. Cancer 110:2716–2725. doi:10.1002/cncr.23094

Hill EK et al. (2011) Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer 117:2643–2651. doi:10.1002/cncr.25832

Vermeer WM et al. (2015) Sexual issues among cervical cancer survivors: how can we help women seek help? Psychooncology 24:458–464. doi:10.1002/pon.3663

Stead ML, Fallowfield L, Brown JM, Selby P (2001) Communication about sexual problems and sexual concerns in ovarian cancer: qualitative study. BMJ 323:836–837

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J (2013) Embodying sexual subjectivity after cancer: a qualitative study of people with cancer and intimate partners. Psychol Health 28:603–619. doi:10.1080/08870446.2012.737466

Hawkins Y et al. (2009) Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer Nurs 32:271–280. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819b5a93

Maughan K, Heyman B, Matthews M (2002) In the shadow of risk. How men cope with a partner's gynaecological cancer. Int J Nurs Stud 39:27–34

Stafford L ,Judd F (2010) Partners of long-term gynaecologic cancer survivors: psychiatric morbidity, psychosexual outcomes and supportive care needs. Gynecol Oncol 118:268-273. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.019.

Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, Wong WK, Hobbs K (2013) Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nurs 36:454–462. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182759e21

Lalos A, Jacobsson L, Lalos O, Stendahl U (1995) Experiences of the male partner in cervical and endometrial cancer—a prospective interview study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 16:153–165. doi:10.3109/01674829509024464

White ID, Faithfull S, Allan H (2013) The re-construction of women's sexual lives after pelvic radiotherapy: a critique of social constructionist and biomedical perspectives on the study of female sexuality after cancer treatment. Soc Sci Med 76:188–196. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.025

Nelson IA (2010) From quantitative to qualitative: adapting the Life History Calendar method. Field Methods 22:413–428. doi:10.1177/1525822x10379793

NVivo. 1990-2013, QSR International: Melbourne, Australia.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N (2000) Qualitative research in health care. Analysing Qual Data. BMJ 320:114–116

Mays N, Pope C (1995) Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ 311:109–112

Murray H, Milhausen RR (2012) Sexual desire and relationship duration in young men and women. J Sex Marital Ther 38:28–40

Hordern AJ, Street AF (2007) Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust 186:224–227

Papadakos J et al. (2012) Informational needs of gynecologic cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol 124:452–457. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.030

Rasmusson E ,Thome B (2008) Women’s wishes and need for knowledge concerning sexuality and relationships in connection with gynecological cancer disease. Sex Disabil 26:207-218. doi: 10.1007/s11195-008-9097-5.

Bloomberg LP Steve Jobs on Apple’s resurgence: “Not a one-man show”, in Bloomberg Business Week 1998: New York.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant no. UL 2010–4760).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors also have full control of the primary data and agree to allow the journal to review the data if requested.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vermeer, W.M., Bakker, R.M., Kenter, G.G. et al. Cervical cancer survivors’ and partners’ experiences with sexual dysfunction and psychosexual support. Support Care Cancer 24, 1679–1687 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2925-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2925-0