Abstract

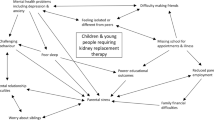

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) can place a great strain on the child and family. As well as the medical and nutritional prescription, each child and family requires an individual psychosocial prescription that requires input from multiprofessional team members. The information needs of each child and family need to be constantly evaluated as well as the choice of therapy in relation to social, psychological and economic factors. Many tertiary units lack adequate “time” to deliver such assessments and coordinate the support and respite care for those on long-term dialysis, especially when significant numbers of children are now accepted onto RRT programmes with co-morbidities. National and international standards are needed for the staffing of comprehensive tertiary paediatric renal units as well as studies evaluating supportive care to families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The diagnosis of chronic illness not only has implications for the child, but also for the whole family. A child with chronic kidney disease (CKD) can be offered treatment, but not cure, even with transplantation. Although the survival rate of children requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) has improved, it remains about 30 times lower than that of peers due mainly to cardiovascular issues [1]. If the child needs to undergo RRT then he/she is subjected to a number of potentially painful procedures as well as growth, educational, psychological and social restraints [2, 3]. With dependence on haemodialysis machines initially designed for adults and the lack of transplantation experience it was hardly surprising that many doubted the wisdom of offering RRT to children in the 1960s and 1970s [4]. However, the increasing experience of specialist units and the advent of chronic peritoneal dialysis in the 1980s enabled children to be treated successfully at home and at some distance from tertiary paediatric renal centres [5, 6]. Such is the current expertise that in those units that have the resources, RRT can be offered from birth [7, 8]. Increasingly, ethical dilemmas arise in relation to the treatment of those with comorbidities or syndromes [9, 10].

Although there are potential benefits in terms of schooling, socialisation and travel costs for children on home dialysis (peritoneal and haemodialysis) compared with hospital haemodialysis, it was naïve of us to expect parents, particularly mothers, to cope with the burden of running a “high dependency unit” at home for their child on home dialysis [11, 12]. Transplantation is the stated goal for all children requiring RRT, but with young infants it may be some time before they reach the size appropriate for transplantation, and support from tertiary nephrology, local paediatric units and primary care may be essential through networks of care [13].

Enough reports have been published to emphasise that being a parent of a child with CKD demands a high level healthcare provider who has to balance problem solving and information gathering with financial and practical skills at a time when physical tiredness and disrupted peer and family support may prevail [14, 15]. A systematic review of 16 qualitative studies on the experiences of parents grouped ten themes into three clusters—intrapersonal (living with constant uncertainty, stress and maintaining vigilance despite fatigue), interpersonal (medicalisation of the parental role, dependence and conflict with staff and disrupted peer relationships) and external issues (management of the medical regimen, transportation, finances, diet restrictions and balancing medical care with domestic responsibilities) [14]. A recent study report from Taiwan showed that depression was significantly more common in caretakers of children on chronic peritoneal dialysis (CPD) compared with controls, with a much lower annual income, higher under-employment and single parent rates in the study group [16]. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) studies in parents of children suffering from renal disease emphasise that mothers experience lower HRQoL and higher psychosocial strains than fathers [17]. The authors emphasised that in the comprehensive care for families with a child suffering from renal disease, screening for psychosocial strains and ways of coping along with applying interventions to strengthen adaptive coping strategies may be a preventative means of “improving parents’ quality of life”.

Quality of life studies in children are also increasingly reporting lower values in children with CKD and RRT, although health status may not necessarily equate to children’s own rated quality of life [18–20]. We are increasingly aware that emotional and behavioural problems occur in children with chronic illness and up to 20 % of children attending a variety of paediatric outpatient clinics had a probable psychiatric disorder [21, 22]. Thirty per cent of 44 patients aged 9–18 years with CKD met the criteria for depression, which was more frequent in those with longstanding disease [23].

Need for psychosocial support

All these points combine to suggest that when managing a child and family with CKD the “psychosocial prescription” is as vital as considering the “medical” and “dietetic prescriptions”. This requires a multiprofessional team that should be provided in a comprehensive tertiary renal centre [24]. The 2013 KDIGO clinical practice guidelines “Care of the patient with progressive CKD” suggested that the multidisciplinary team should include, or have access to, dietary counselling, education and counselling about different RRT modalities, transplant options, vascular access surgery, and ethical, psychological and social care [25]. This recommendation was ungraded as it was appreciated that different healthcare systems, geographical issues and economic considerations result in variable abilities to implement recommendations [26, 27].

A survey completed by 3,867 adult renal patients in Europe found that one third cannot choose their treatment or are not sure about how much their choice counted, one quarter felt that they were not really involved in deciding about their treatment and one third did not have access or were dissatisfied with the access to a social worker or dietician [28]. The National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK emphasised patient-centred care in its guidance on chronic kidney disease in 2008 and also emphasised the involvement of young people in decision-making, especially at the time of transition to adult centres [29]. NICE guidance on peritoneal dialysis in 2011 additionally emphasised that children should have information presented to them in a way suitable for their developmental age using play therapists [30].

Although there is strong agreement that multiprofessional support is an essential aspect of CKD care in children, little has been written about the staffing ratios and organisation of such teams. The British Association of Paediatric Nephrology working party report of 2003, reviewing multiprofessional services, suggested standards for social workers, psychologists, play and education specialists as well as nursing and renal dietetic support [24]. The recommendations from the 2003 report were reiterated in a recent 2011 guide emphasising the need for shared care with local units by outreaching from the central unit and creating renal networks [13]. The suggested that the staffing ratios in the 2003 report might not have been reached in many tertiary units. A current study of 14 paediatric renal units in Europe showed major deficits in psychosocial provision by designated professionals, with only 4 out of 14 units having a full-time social worker, 7 a part-time one and 3 none. Similarly, a full-time psychologist was available in 3 units, 9 a part-time one and 2 units had no psychological support [31].

Delivery of psychosocial care

Paediatric healthcare professionals are focused on “minimising the handicap and maximising the potential” of any child with chronic illness. This mandate involves all aspects of growth and development including educational achievement and social and psychological functioning. All members of the paediatric renal team are therefore involved in psychosocial care, but the deficiencies in team support detailed above suggest that our efforts to provide continued information and support might be hampered by lack of “team time” and home visits with respite care may not be feasible [32].

In adult practice the autonomous patient can be involved in treatment choices using evidence-based decision-making [33]. Children also need to be involved in decision-making whenever possible, but in general we make decisions based on their best interests. This may encompass “greater” best interests taking into account family circumstances, carer/patient capabilities, greater family support and the needs of other siblings. Age and distance from the tertiary centre are also major factors [31]. Choice of therapy can be a complex decision, but the simple tenet is that better informed patients make better informed decisions. Different families have different information needs and one size does not fit all [34]. Parents of a lower socio-economic status have greater information needs and team members need to tailor information to the needs of individual families. We are increasingly aware that immigration status, race and poverty have important influences on the choice of therapy [35]. Late referrals of children with CKD also occur in paediatric practice along with patients who crash-land onto dialysis because of severe nephritis or acute kidney injury. Such patients pose a particular challenge and may need further specialist intensive psychosocial support if intensive care is required and if there is any evidence of a post-traumatic stress disorder [36].

Paediatric renal units often have specialist nurses for dialysis or transplantation and although there is no randomised study it is generally felt that visits to the home to discuss dialysis and treatment options by the nurse and/or social worker help the family to absorb the information and discussions in a more relaxed atmosphere than at the clinic [32]. It also gives an opportunity for siblings to be involved in the discussions, which may help to allay some of their anxiety [37]. A 15-month community-based, family-supported intervention by “experienced mothers” and child life specialists in children with diabetes mellitus, sickle cell anaemia, cystic fibrosis or moderate/severe asthma, showed modest positive effects in all diagnostic groups and may be particularly relevant to those with low self-esteem, which also occurs with CKD [38]. Home visits to review children on CPD has a proven advantage in detecting and anticipating poor practice that might lead to complications such as peritonitis [39]. Increasing interest in home haemodialysis certainly necessitates robust home support mechanisms [40].

Preventing psychosocial issues

Children can be easily upset by invasive procedures, despite the use of local anaesthetic creams and sprays. Many have varying degrees of needle and procedural phobia, which makes aspects of their care very stressful to patient, family and staff [41]. The work of play therapists or child life specialists, often in conjunction with the psychologists, in preparing children for procedures throughout their RRT cannot be over-emphasised [42]. Experience would also suggest that the presence of a psychologist in close proximity to the renal team, particularly participating in a joint clinic, allows early referral for assessment and advice, especially when families are attending from some distance. Recently developed QoL questionnaires are easy to complete by patients and may act as a focus for early or longitudinal assessments [19, 20]. There is increasing recognition of depression as being a major mortality risk in adult renal patients and depression may be more frequent than we have recognised in paediatric patients also [43].

Experience suggests that a multiprofessional team of play therapist, social worker, psychologist and family/systemic psychotherapist in conjunction with medical/nursing colleagues needs to constantly address the potential and actual trauma and upset that children and young people undergo with effective evidence-based interventions, such as distraction and combined cognitive behavioural therapy [44, 45]. Early referral is advocated with regular team meetings to facilitate knowledge transfer.

Socio-economic issues

As well as the information and psychological needs of children and their families, the financial impact of having a child with a chronic illness can be considerable, with often one parent giving up employment, as well as the additional costs of modifications to the family routine and travel. It is essential that each family is assessed by a social worker so that the burden of care is understood and resources such as grants can be maximised [46]. Transplantation is the preferred modality of treatment for children needing RRT, but again the financial impact on the family of living related donor transplantation, often from mothers, needs to be understood and carefully assessed as well as the lasting impact on family dynamics [47, 48].

Education

Academic performance is impaired and long-term employment possibilities diminished in young people with CKD [49, 50]. Although these issues have been documented, little practical advice has been forthcoming on tackling the issues. Absenteeism may remain a problem in children on home dialysis or post-transplant and those on haemodialysis may lose 60 % of their school contact time if on conventional three-times-a-week in-centre dialysis. Although educational support on hospital haemodialysis is mandated in many countries, it was only available in 10 of the 14 European units surveyed [31]. In our own unit we endeavour to maintain a close liaison with school, whether the child is on haemodialysis, CPD or post-transplant [51]. One of the teachers attends clinic to liaise with families and extra educational support has been provided during summer holidays. Visits to the school by either the dialysis nurse and/or teacher ensures that the dialogue with local teachers remains active [32].

Respite care

The concept of an annual holiday for children on dialysis is well recognised [52, 53]. The holiday “respite” gives the child the opportunity to build self-esteem and participate in activities that may be restricted during the rest of the year. For the parents there is the obvious lessening of the burden of care during the time off. Some children may not wish to socialise with their renal peers and, indeed, jealousy can arise in siblings. Home peritoneal dialysis and the use of portable automatic cyclers means that children can enjoy a holiday with the family in many locations where supplies can be delivered [32]. Haemodialysis can also be arranged at a different location, but there are more restrictions.

Recognition of the constant demands upon parents of technology-dependent children suggests that respite care within the home or occasionally hospice care might prevent “burn out” of carers, predominantly mothers [54, 55]. A child on CPD will become landlocked in their own home, as even close relatives may not feel competent enough to babysit the child on home dialysis or overnight feeds. Babysitting can be provided by experienced nurses from the unit and extended to daytime nursing support so that carers can have time to themselves as well as attending to the needs of other siblings [37]. Transport and parking issues are constantly referred to by families with a child on haemodialysis and the provision of escorts to accompany children and relieve parents has been recommended.

Youth work

The success of paediatric RRT means that there is an increasing number of patients needing preparation for transition and subsequent transfer from paediatric to adult units [56, 57]. However, before reaching the age when transfer is appropriate young people have to negotiate their way through adolescence, which brings additional psychosocial concerns with reported levels of very poor adherence [58]. Youth workers provide one-to-one support and group work for young people, building up their self-esteem and assisting with their adaptation during this transitional period before transfer to adult services [59, 60]. In our own unit where there is no defined adolescent unit, they have become invaluable in supporting young people and the model has now been extended to supporting young adults in the adult renal unit [61].

Recent research has highlighted that CKD patients aged 12–24 years need support and advice to improve autonomy, self management skills and the emotional burdens of future uncertainties [62]. In 377 young adults aged 22–31 years who have grown up with a somatic condition there was worse QoL and feelings of anxiety (29.7 %) and depression (17 %) in those claiming disability benefits [63]. The author suggests that future research might need to focus on emotional functioning and specific psychosocial support aimed at workforce participation.

Conclusions

Psychosocial support refers to an important area of the holistic care that is required for all children and families with CKD, especially those undergoing RRT. Research in this field is hampered by the difficulties of small numbers of patients and scattered paediatric units offering different levels of support. The qualitative and quantitative research that is available and the cumulative experience of over 30 years with RRT suggest that information and support for the child and the carers is essential. These beliefs have been given further impetus by quality of life studies that are now being incorporated into the routine care plan for children with CKD. Such studies have highlighted the need for the increased information and support, which is necessary. National and international associations need to develop and promote appropriate standards and multiprofessional staffing of comprehensive renal units so that the psychosocial prescription can be fulfilled.

Summary points

-

1.

Addressing the psychosocial “prescription” for children and families requiring RRT is as important as medical and dietetic prescriptions, as the burden of care and emotional burden are high.

-

2.

The needs of each child and family must be individualised and constantly assessed by several members of the multiprofessional renal team, who need to help the whole family adjust to the changing challenges of chronic illness into adulthood.

-

3.

National and international standards are needed to define staffing levels and standards so that tertiary paediatric renal units can provide appropriate psychosocial care.

Multiple choice questions (Answers are provided following the reference list.)

-

1.

Psychosocial care of families with children requiring renal replacement therapy does NOT require:

-

a)

Evaluation of information needs of child and family

-

b)

Evaluation of support needs including social work assessment

-

c)

Discussion and information sharing at multiprofessional team meetings

-

d)

Liaison with clinical psychology for problems with child, siblings and families

-

e)

Routine evaluation by child and adolescent psychiatrist

-

a)

-

2.

Children who are needle phobic or apprehensive of potentially painful procedures do NOT require:

-

a)

Preparation before procedures by play therapists or child life specialists

-

b)

Use of local anaesthetic creams or sprays

-

c)

Routine use of general anaesthetics

-

d)

Distraction techniques to divert attention

-

e)

Early referral to clinical psychologist

-

a)

-

3.

Which of the following statements regarding educational issues in children on RRT is TRUE:

-

a)

Young people on RRT have comparable educational outcomes to peers

-

b)

Uraemia has no effect on cognitive function

-

c)

Haemodialysis prevents children doing schoolwork during treatment

-

d)

Absenteeism from school is at low levels (<5 %) in children following renal transplantation

-

e)

Liaison between hospital and home school teachers facilitates educational progress

-

a)

-

4.

Which of the following statements in respect of adolescent patients requiring RRT is TRUE

-

a)

Adolescents should all be treated in an adolescent unit

-

b)

Treatment choices should be made by parents in all those younger than 14 years of age

-

c)

Transition and transfer to adult renal centres should be completed by 16 years of age

-

d)

Poor adherence to medication occurs only in poor socio-economic circumstances

-

e)

Youth workers provide personal and group support for this group of patients

-

a)

-

5.

Which of the following statements is NOT TRUE in treating children with RRT

-

a)

Ethical decisions should be based upon “greater best interests” of the child and family

-

b)

Immigration status and race have no impact upon choice of therapy

-

c)

Strategies for home support may alleviate the burden of care and prevent “burn out” in families

-

d)

Health-related quality of life measures may be a valuable tool for longitudinal assessment of children on RRT as well as their parents

-

e)

The “psychosocial prescription” is of minor importance in treating children with RRT

-

a)

References

Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ (2012) Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol 27:363–373

Tjaden L, Tong A, Henning P, Groothoff J, Craig JC (2012) Children’s experiences of dialysis: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Arch Dis Child 97:395–402

Groothoff JW, Grootenhuis MA, Offringa M, Stronks K, Hutten GJ, Heymans HS (2005) Social consequences in adult life of end-stage renal disease in childhood. J Pediatr 146:512–517

Riley CM (1964) Thoughts about kidney homotransplantation in children. J Pediatr 65:797–800

Chantler C, Carter JE, Bewick M, Counahan R, Cameron JS, Ogg CS, Williams DG, Winder E (1980) 10 years’ experience with regular haemodialysis and renal transplantation. Arch Dis Child 55:435–445

Von Lilien T, Salusky IB, Boechat I, Ettenger RB, Fine RN (1987) Five years’ experience with continuous ambulatory or continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis in children. J Pediatr 111:513–518

Zurowska A, Fischbach M, Watson AR, Edefontiport A, Stefanidis CJ, on behalf of the European Pediatric Dialysis Working Group (2012) Clinical practice recommendations for the care of infants with stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD5). Pediatr Nephrol 28:1739–1748

Mekahli D, Shaw V, Ledermann SE, Rees L (2010) Long-term outcome of infants with severe chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5:10–17

Neu AM, Sander A, Borzych-Duzalka D, Watson AR, Valles PG, Ha IS, Patel H, Askenazi D, Balasz-Chmielewska I, Lauronen J, Groothoff JW, Feber J, Schaefer F, Warady BA, IPPN investigators (2012) Comorbidities in chronic paediatric peritoneal dialysis patients: a report of the International Pediatric Peritoneal Dialysis Network. Perit Dial Int 32:410–418

Vidal E, Edefonti A, Murer L, Gianoglio B, Maringhini S, Pecoraro C, Sorino P, Leozappa G, Lavoratti G, Ratsch IM, Chimenz R, Verrina E, Italian Registry of Paediatric Chronic Dialysis (2012) Peritoneal dialysis in infants: the experience of the Italian Registry of Paediatric Chronic Dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27:385–395

Watson AR (1997) Stress and burden of care in families with children commencing renal replacement therapy. Adv Perit Dial 13:300–304

Brownbridge G, Fielding DM (1994) Psychosocial adjustment and adherence to dialysis treatment regimes. Pediatr Nephrol 8:744–749

Report of a Working Party of Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, British Association for Paediatric Nephrology and NHS Kidney Care (2011) Improving the standards of care of children with kidney disease through paediatric nephrology networks. www.rcpch.ac.uk/networks Accessed 16 April 2013

Tong A, Lowe A, Sainsbury P, Craig JC (2008) Experiences of parents who have children with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics 121:349–360

Aldridge MD (2008) How do families adjust to having a child with chronic kidney failure? A systematic review. Nephrol Nurs J 35:157–162

Tsai TC, Lui SI, Tsai JD, Chou LH (2006) Psychosocial effects on caregivers for children on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int 70:1983–1987

Wiedebusch S, Konrad M, Foppe H, Reichwald-Klugger E, Schaefer F, Schreiber V, Muthny FA (2010) Health-related quality of life, psychosocial strains, and coping in parents of children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol 25:1477–1485

Buyan N, Turkmen MA, Bilge I, Baskin E, Haberal M, Bilginer Y, Mir S, Emre S, Akman S, Ozkaya O, Fidan K, Alpay H, Kavukcu S, Sever L, Ozcakar ZB, Dogrucan N (2010) Quality of life in children with chronic kidney disease (with child and parent assessments). Pediatr Nephrol 25:1487–1496

Neul SK, Minard CG, Currier H, Goldstein SL (2013) Health-related quality of life functioning over a 2-year period in children with end-stage renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol 28:285–293

Heath J, Mackinlay D, Watson AR, Hames A, Wirz L, Scott S, Klewchuk E, Milford D, McHugh K (2011) Self-reported quality of life in children and young people with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 26:767–773

Hysing M, Elgen I, Gillberg C, Lie SA, Lundervold AJ (2007) Chronic physical illness and mental health in children. Results from a large-scale population study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 48:785–792

Glazebrook C, Hollis C, Heussler H, Goodman R, Coates L (2003) Detecting emotional and behavioural problems in paediatric clinics. Child Care Health Dev 29:141–149

Kogon AJ, Vander Stoep A, Weiss NS, Smith J, Flynn JT, McCauley E (2013) Depression and its associated factors in pediatric chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 28:1855–1861

Report of a Working Party of the British Association for Paediatric Nephrology (2003) Review of multi-professional paediatric nephrology services in the UK—towards standards and equity of care

KDIGO (2012) Clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Chapter 5: referral to specialists and models of care. Kidney Int 3:112–119

Warady BA, Chadha V (2007) Chronic kidney disease in children: the global perspective. Pediatr Nephrol 22:1999–2009

Bruce MA, Beech BM, Sims M, Brown TN, Wyatt SB, Taylor HA, Williams DR, Crook E (2009) Social environmental stressors, psychological factors, and kidney disease. J Investig Med 57:583–589

European Kidney Patients Federation (CEAPIR) (2012). Unequal treatment for kidney patients in Europe. www.ceapir.org/wb/index.php Accessed 2 April 2013

NICE guidance (2008) Chronic kidney disease CG73 www.nice.org.uk/CG73 Accessed 2 April 2013

NICE guidance (2011) Peritoneal dialysis www.nice.org.uk/CG125 Accessed 2 April 2013

Watson AR, Hayes WN, Vondrak K, Ariceta G, Schmitt CP, Ekim M, Fischbach M, Edefonti A, Shroff R, Holta T, Zurowska A, Klaus G, Bakkaloglu S, Stefanidos C, Van de Walle J (2013) Factors affecting choice of renal replacement therapy in European Pediatric Nephrology Units. Pediatr Nephrol. doi:10.1007/s00467-013-2555-z

Watson AR (1995) Strategies to support families of children with end-stage renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol 9:628–631

Moss AH (2010) Revised dialysis clinical practice guideline promotes more informed decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5:2380–2383

Collier J, Pattison H, Watson AR, Sheard C (2001) Parental information needs in chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. Eur J Paediatr 160:31–36

Schoenmaker NJ, Tromp WF, van der Lee JH, Adams B, Bouts AH, Collard L, Cransberg K, van Damme-Lombaerts R, Godefroid N, van Hoeck KJ, Koster-Kamphuis L, Lilien MR, Raes A, Groothoff JW (2012) Disparities in dialysis treatment and outcomes for Dutch and Belgian children with immigrant parents. Pediatr Nephrol 27:1369–1379

Rossi A, De Ranieri C, Tabarini P, Di Ciommo V, Di Donato R, Biondi G, Parisi F (2011) The department of psychology within a pediatric cardiac transplant unit. Transplant Proc 43:1164–1167

Batte S, Watson AR, Amess K (2006) The effects of chronic renal failure on siblings. Pediatr Nephrol 21:246–250

Chernoff RG, Ireys HT, DeVet KA, Kim YJ (2002) A randomized, controlled trial of a community-based support program for families of children with chronic illness: pediatric outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156:533–539

Ellis EN, Blaszak C, Wright S, Van Lierop A (2012) Effectiveness of home visits to pediatric peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 32:419–423

Hothi DK, Stronach L (2012) Home haemodialysis for children. Br J Renal Med 17:4–7

Duff AJ (2003) Incorporating psychological approaches into routine paediatric venepuncture. Arch Dis Child 99:931–937

Bandstra NF, Skinner L, Leblanc C, Chambers CT, Hollon EC, Brennan D, Beaver C (2008) The role of child life in pediatric pain management: a survey of child life specialists. J Pain 9:320–329

Hemandez EG, Loza R, Vargas H, Jara MF (2011) Depressive symptomatology in children and adolescents with chronic renal insufficiency undergoing chronic dialysis. Int J Nephrol 2011:79869

Chambers CT, Taddio A, Uman LS, McMurtry CM, HELPinKIDS Team (2009) Psychological interventions for reducing pain and distress during routine childhood immunisations: a systematic review. Clin Ther 31 [Suppl 2]:S77–S103

Uman LS, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, Kisely S (2006) Psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD005179

Lindley LC, Mark BA (2010) Children with special health care needs: impact of health care expenditures on family financial burden. J Child Fam Stud 19:79–89

Roodnat JI, Laging M, Massey EK, Kho M, Kal-van Gestel JA, Ijzermans JN, van de Wetering J, Weimar W (2012) Accumulation of unfavourable clinical and socio-economic factors precludes living donor kidney transplantation. Transplantation 93:518–523

Gordon EJ (2012) Informed consent for living donation: a review of key empirical studies, ethical challenges and future research. Am J Transplant 12:2273–2280

Duquette PJ, Hooper SR, Wetherington CE, Icard PF, Gipson DS (2007) Brief report: intellectual and academic functioning in pediatric chronic kidney disease. J Pediatr Psychol 32:1011–1017

Icard PF, Hower SJ, Kuchenreuther AR, Hooper SR, Gipson DS (2008) The transition from childhood to adulthood with ESRD: educational and social challenges. Clin Nephrol 69:1–7

Poursanidou K, Garner P, Watson A (2008) Hospital-school liaison: perspectives of health and education professionals supporting children with renal transplants. J Child Health Care 12:253–267

Warady BA (1994) Therapeutic camping for children with end stage renal disease. Pediatr Nephrol 8:387–390

Watson A, Hilton D, Hackett D (2010) Therapeutic recreation camps to provide a residential experience for young people in transition to adult renal units. Pediatr Nephrol 25:787–788

Thyen U, Kuhlthau K, Perrin JM (1999) Employment, child care, and mental health of mothers caring for children assisted by technology. Pediatrics 103:1235–1242

Watson AR (1996) Home health and respite care. Perit Dial Int 16:551–553

Bell L (2007) Adolescents with renal disease in an adult world: meeting the challenge of transition of care. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22:989–991

Watson AR, Harden P, Ferris M, Kerr PG, Mahan J, Ramzy MF (2011) Transition from pediatric to adult renal services: a consensus statement by the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) and the International Pediatric Nephrology Association (IPNA). Pediatr Nephrol 26:1753–1757

Haller DM, Sanci LA, Sawyer SM, Patton G (2008) Do young people’s illness beliefs affect healthcare? A systematic review. J Adolesc Health 42:436–449

Watson AR (2004) Hospital youth work and adolescent support. Arch Dis Child 89:440–442

Hilton D, Jepson S (2012) Evolution of a youth work service in hospital. Nurs Child Young People 24:14–18

Harden PN, Walsh G, Bandler N, Bradley S, Lonsdale D, Taylor J, Marks SD (2012) Bridging the gap: an integrated paediatric to adult clinical service for young adults with kidney failure. BMJ 344:e3718

Tong A, Henning P, Wong G, McTaggart S, Mackie F, Carroll RP, Craig JC (2013) Experiences and perspectives of adolescents and young adults with advanced CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 61:375–384

Verhoof E, Maurice-Stam H, Heymans H, Grootenhuis M (2013) Health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression in young adults with disability benefits due to childhood-onset somatic conditions. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 7:12

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Answers:

1 e

2 c

3 e

4 e

5 b

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watson, A.R. Psychosocial support for children and families requiring renal replacement therapy. Pediatr Nephrol 29, 1169–1174 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-013-2582-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-013-2582-9