Abstract

Obese adolescents spend a disproportionate time in screen-based activities and are at higher risk for clinical depression compared to their normal-weight peers. While screen time is associated with obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors, little is known about the relationship between screen time and mental health. This cross-sectional study examines the association between duration and types of screen time and depressive symptomatology (subclinical symptoms) in a sample of 358 (261 female; 97 male) overweight and obese adolescents aged 14–18 years. Self-report measures assessed depressive symptoms and time spent in different types of screen behavior (TV, recreational computer use, and video games). After controlling for age, ethnicity, sex, parental education, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, caloric intake, carbohydrate intake, and intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, total screen time was significantly associated with more severe depressive symptomatology (β = 0.21, p = 0.001). After adjustment, time spent playing video games (β = 0.13, p = 0.05) and recreational computer time (β = 0.18, p = 0.006) was associated with depressive symptoms, but TV viewing was not.

Conclusions: Screen time may represent a risk factor or marker of depressive symptomatology in obese adolescents. Future intervention research should evaluate whether reducing screen exposure reduces depressive symptoms in obese youth, a population at increased risk for psychological disorders.

What is Known: • Screen time is associated with an increased risk of obesity in youth. • Screen time is associated with an adverse cardio-metabolic profile in youth. |

What is New: • Screen time is associated with more severe depressive symptoms in overweight and obese adolescents. • Time spent in recreational computer use and playing video games, but not TV viewing, was associated with more severe depressive symptoms in overweight and obese adolescents. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity in children and youth is reaching epidemic proportions, with recent epidemiological studies indicating that approximately one third of North American adolescents are overweight or obese [49, 62]. These rates represent a serious public health crisis given that obesity tracks from childhood into adulthood, and obesity increases the risk of morbidity and mortality [15]. However, often overlooked are the psychosocial consequences of obesity, which include weight-based teasing [16], bullying, stigma, discrimination, and bias [60]. Thus, it is not surprising that overweight and obese adolescents also report greater depression than their normal weight peers [23].

The World Health Organization forecasts that depression in youth will be one of the top contributors to the burden of disease by 2020 [52]. The prevalence of depression peaks in mid to late adolescence [76], with epidemiological studies in North America indicating that approximately 5–9 % of adolescents met criteria for clinical depression (i.e., major depressive disorder) [8, 58]. A recent systematic review indicates that an additional 9–16 % of youth report sub-clinical levels of depressive symptoms, as measured by self-reported questionnaires [5]. The high rate of depressive symptoms among adolescents is alarming given it is a central risk factor for suicide [47], the second leading cause of death in youth. Depression, and sub-clinical depressive symptoms, have also been linked to academic failure, poor interpersonal relationships, behavioral problems, and substance abuse in youth [40]. Moreover, longitudinal research shows that depressive symptoms track from adolescence and is predictive of clinical depression into adulthood [57]. Thus, identifying determinants of subclinical manifestations of depressive symptomatology (e.g., cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms), may aid the development of treatment and prevention strategies among adolescents.

Sedentary behavior—defined as a form of waking behavior expending <1.5 metabolic equivalents in a sitting or reclining position [48]—is now recognized as a distinct construct from physical (in) activity and may impact health through different mechanisms [25]. Screen time (ST) is the most prevalent form of sedentary behavior in children and youth, with the vast majority of North American and Australian youth exceeding guidelines of 2 h per day [4, 55, 69]. In fact, epidemiological data indicate youth in Australia [28] and Europe [65] accrue at least 4 h per day, while youth in Canada and the USA accrue up to 7–8 h per day of ST [6, 61]. This extreme amount of daily ST has been reliably associated with an increased risk of obesity [3, 24] and adverse cardiometabolic profile in youth independent of physical activity [10, 17, 22, 26]; however, a paucity of research has examined the association between ST and mental health indicators, such as mood or symptoms of depression.

The few studies that have investigated this link have shown mixed findings. While there is some evidence that ST is associated with an increased risk of depression in adolescents [9, 43, 45, 59, 67], other studies have shown no association [11, 29]. Importantly, of the five studies in which ST was associated with depressive symptoms in youth, two studies controlled for socio-demographic characteristics only [59, 67], another controlled for body mass index (BMI) and dietary intake (fruit and vegetable intake) but not physical activity [9], and the last two controlled for physical activity and BMI but not diet [43, 59]. Thus, no study to date has controlled for sociodemographics, BMI, physical activity, and diet. These are significant limitation given that ST is associated with increased body fatness and reduced physical activity levels in youth [44], as well as poor dietary habits [75]. In addition, these variables, as well as sociodemographic variables (i.e., parent education [59]) are also associated with depressed mood in youth [14, 21, 30, 63]. Carbohydrate intake may be particularly important to control for given ST is associated with increased intake of high carbohydrate snack foods and sugar-sweetened beverages [12, 51, 75] and carbohydrate intake is known to impact mood via serotonin release [77]. Moreover, given that time spent using computers and playing video games has equaled or surpassed time spent watching TV among youth [7, 61], and few studies have examined how individual ST behaviors such as watching TV, playing video games, and computer use relate to depression, with existing studies showing inconsistent findings [11, 45, 59], further inquiry is needed.

No study to date has examined the relationship between ST and depressive symptoms in overweight or obese youth, a population that is clinically relevant to study given obese youth engage in more ST [70] and report more severe depressive symptoms [23] than their normal weight peers. Elucidating a better understanding of the association between duration and types of screen time behaviors and mental health may be critical to developing more effective strategies to prevent or treat depression in this high risk group of youth.

The present study was the first to examine the independent relationships between the duration (time spent) and types of self-reported sedentary ST behaviors (i.e., TV viewing, seated video games, and recreational computer time) and depressive symptomatology in overweight and obese adolescents. It was hypothesized that longer duration of screen time would be associated with more severe symptoms of depression, after controlling for a wide set of possible confounders.

Materials and methods

Participants

All participants were either overweight (85th to 94th BMI percentile) or obese (≥95th BMI percentile) as determined by age and sex cut-off values from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) growth charts [35]. Participants were recruited from the Ottawa/Gatineau, Canada region as potential participants in the Healthy Eating, Aerobic, and Resistance Training in Youth (HEARTY) trial, a randomized controlled trial examining the effects of resistance training, aerobic training, or both on body fat in obese youth (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT00195858). Participants were recruited by posters and advertisements in the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario’s endocrine/obesity clinic, by radio and bus advertisements, and flyers in the community, and physicians’ offices. Only participants who were post-pubertal (Tanner stage IV or V) were included. Assessments, including physical examination and questionnaires, were conducted at the time of entry into the trial. Results reported herein represent baseline data collected before the exercise intervention was implemented and collected between 2005 and 2010. Participants were tested individually by our research staff. The methodology of this trial has been described in detail elsewhere [2].

Informed written consent from each participant was obtained in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines for human subjects. In the case of minors under the age of 16 years, written consent was also obtained by parents or legal guardians. The current study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Boards of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) (protocol no. 05/04E) and The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (protocol no. 2004219-01H).

Measurement

Demographics

Participant age, sex, and ethnicity were collected by self-report.

Anthropometrics

A manual scale and stadiometer (Health O Meter, Continental Scale Corp, Bridgeview, ILL) was used to measure participants’ height (meters, m) and weight (kilograms, kg) while they wore light clothing and no shoes. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2). All assessments of anthropometric variables were performed in a sensitive manner and in a private room by an experienced female research coordinator.

Screen time behavior

ST was assessed by asking participants to report how much time, in hours per day, they spent watching television, playing seated/inactive video games (excluding computer games), and using the computer for recreational reasons (excluding school work) [2]. The three types of screen behaviors were aggregated to make up a measure of total screen time used in the analyses. These questions and response formats reflecting the collection of continuous data are consistent with epidemiological studies assessing the relationship between the same types of screen time (TV, video games, computer use) and various health outcomes in youth [38, 39].

Physical activity

Participants recorded the physical activities performed over 3 days using the Previous Day Physical Activity recall, a valid self-report measure of physical activity in youth (including obese youth) [74]. Physical activity duration was assessed based on self-report questions, such as “On average, how long do you participate in some sort of physical activity each day – with physical activity being cumulative not consecutive?” Participants were asked to choose one of the following responses using a Likert-type rating scale: (1) less than 5 min; (2) 5 to 15 min; (3) 15 to 30 min; (4) 30 to 45 min; (5) 45 to 60 min; or (6) greater than 60 min. Physical Activity intensity was assessed by the question of “On average, how would you describe the intensity of most of your physical activity? Response ratings were as follows: 1 = light, 2 = moderate; 3 = vigorous.

Food intake

Energy intake (including total kilocalories and percentage of kilocalories consumed from fat, protein, and carbohydrates) was assessed using food diaries under the supervision of a registered dietitian [2]. Participants were asked to complete food diaries for 3 days (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day) during the baseline week of testing. The mean intake was averaged across 3 days for analysis. This self-report method of assessing free living food intake has been widely used and has demonstrated adequate reliability [68]. Dietary composition was analyzed using software (The Food 324 Processor SQL, 2006 ESHA Research, Salem, OR, USA).

Depressive symptomatology

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 27 items reflecting cognitive, affective, behavioral, and somatic symptoms of depression in children aged 6 to 17 years [33]. The items are rated on a 3-point scale indicating symptom severity (0 = no presence of symptom, 1 = symptom is present and mild, and 2 = highest severity possible). Total scores on the CDI range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptomatology. This inventory has strong psychometric properties. It displays high internal consistency scores ranging from r = 0.71 to r = 0.89, and test-retest reliability coefficients ranging from r = 0.50 to r = 0.83, with time intervals of 2–3 weeks, and good concurrent validity [33]. The CDI also demonstrates good discriminant validity when classifying children and youth with no significant psychopathology versus those who were depressed [33], and it is the most frequently used scale to measure depression in children [71].

Statistical analysis

The data were validated by examining maximum and minimum scores to ensure that each item was scored correctly and within the proper scoring range. All assumptions for multiple regression analyses were satisfied. The independent effect of ST (time spent in TV + computer use + video games in hours/day) on depressive symptoms represented by the total raw score on the CDI (dependent variables) was examined using multiple linear regression models, whereby age, sex, parent education, ethnicity, BMI, physical activity duration (minutes/day), physical activity intensity, caloric intake (kcals/day), carbohydrate intake (grams/day), and sugar-sweetened beverage intake (kcals/day) were entered as covariates as research has shown these variables can impact depressive symptoms in youth [18, 37, 59, 71]. These analytic procedures were repeated to examine associations between the types of ST (TV, video gaming, and recreational computer time) and depressive symptoms in the manner described above. Each regression included a sex × ST interaction to evaluate whether the relationship between ST and depressive symptoms was differentially influenced by sex. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 19) was used to perform all statistical analyses. A two-tailed p value ≤0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

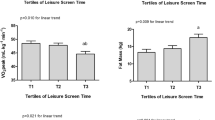

The sample consisted of 261 girls and 97 boys aged 14–18 years, with a mean age of 15.6 ± 1.4 years. The mean BMI was 34.5 ± 4.5 kg/m2. The majority of the sample (71 %) was Caucasian, 11 % were African-Canadian, 3 % Arabic, 3 % Hispanic, 3 % Asian, 2 % First Nations, 5 % mixed race, and 2 % categorized as “other.” Descriptive characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Ninety-three percent of the sample was obese (333 out of 358). The sample spent a significant amount of hours per day in ST, whereby participants accrued 2.9 h per day in TV viewing, 2.3 h per day in computer time, and 0.5 h per day playing video games. On average, boys had a higher BMI, reported more time spent engaged in video games and overall screen time, reported greater caloric intake, and exhibited lower scores on depressive symptoms. However, no sex differences were found for age, time spent engaged in TV or recreational computer use, physical activity duration or intensity, carbohydrate intake, or sugar-sweetened beverage intake.

Table 2 presents results from the multiple regression analyses on total screen time and depressive symptoms. After adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, parental education, BMI, physical activity duration, physical activity intensity, caloric intake, carbohydrate intake, and sugar-sweetened beverage intake, overall time spent in ST was associated with mores severe depressive symptomatology (β = 0.21, p = 0.001). The sex × ST duration interaction was not significant.

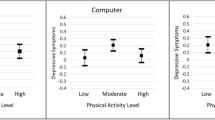

Table 3 presents results from the multiple regression analyses assessing the independent association between type of screen time and depressive symptoms. After adjustment, time spent playing video games (β = 0.13, p = 0.05) and recreational computer time (β = 0.18, p = 0.006) was associated with more severe depressive symptoms, but TV only showed a trend toward a significant association (β = 0.11, p = 0.09). In all regressions, the ST by sex interaction was not associated with depressive symptoms, indicating the relationship between duration and type of ST and depression was not influenced by sex.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to examine independent associations between the duration (time spent) and type of ST and depressive symptomatology in overweight and obese adolescents. We found overall ST was independently positively associated with depressive symptoms. Regarding the types of ST behavior, time spent in recreational computer use and video gaming, but not TV viewing, were positively associated with depressive symptoms, controlling for a broad range of confounders. The interactions between sex and total ST and sex by types of ST behaviors and depression scores were not significant, suggesting that the relationship between ST and depressive symptoms did not differ by sex.

Very few studies have examined the relationship between ST and depression in youth, a population that amass a high volume of ST and who is vulnerable to depression. Consistent with our findings, Primack and colleagues [59] found in more than 4000 adolescents, that overall ST exposure during adolescence increased the risk of depression, findings that are consistent with some studies [9, 43] but not others [11, 29]. Methodological differences across the studies may explain, in part, the discrepant findings. For example, although the sample size was large, Casiano and colleagues [11] employed a diagnostic clinical interview designed to diagnose major depressive disorder (i.e., clinical depression) rather than examining depressive symptoms on a continuous scale as did Primack et al. [59] with the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale. Given the vast majority of the sample was not clinically depressed, along with the fact that the self-reported media use was recalled for the past 3 months—as opposed to a 1-week recall for Primack et al. [59]—these factors could explain their null findings. Hume et al. [29] did examine depressive symptoms using the same assessment tool as Primack et al. [59], but the sample size was relatively small, thus lack of power may have contributed to their null findings. Furthermore, Hume et al. [29] utilized higher cut off scores for the threshold for depression (15 compared to 10), which could also explain the lack of association between TV viewing and depression in adolescents.

Few studies have examined how specific types of ST relate to depression. Our findings that video games but not TV are independently associated with depressive symptoms are consistent with those by Mathers et al. [45]. Similarly, previous studies found that TV showed no association to depressive symptoms [11, 50], consistent with our findings. It is interesting to note that the significant association between video gaming and depression was evident with 35 min/day of mean time spent playing video games in the Mathers et al. [45] study, whereas in our sample the mean time spent engaged in video games was 84 min/day in boys and only 10 min/day in girls. This amount of video game exposure is considerably less than the national average of 123 min/day for boys and 40 min/day for girls [39]. While Primack et al. [59] found that TV was predictive of depression in a large longitudinal sample of adolescents, that study did not measure recreational computer use or seated video games, but instead used a hybrid measure of computer games, thus it is uncertain how these screen behaviors independently impacted depression. While we found video gaming was independently associated with more severe depressive symptoms, other research in adolescents found inverse associations [11, 50]. Our finding that recreational computer use was positively associated with depressive symptoms is consistent with some studies [43, 64, 78], but not others [42, 45]. The conflicting results may be explained, in part, by differences in methodology across studies such as differing depression questionnaires, covariates, and sample characteristics. For example, the current study is the only sample comprised with overweight or obese adolescents. Taken together, the emerging data indicate that types of ST behaviors may differentially relate to depressive symptoms and mental health, and further longitudinal study is needed to gain a better understanding of these associations and underlying mechanisms in both overweight/obese and normal-weight youth.

In considering some mechanisms by which ST may contribute to depressed mood, some possible explanations are offered. As noted by Primack et al. [59] adolescents with high volume of exposure to screens may be socially isolating themselves [27, 46]. In addition, excessive ST, which typically occurs in the evening, may reduce sleep which can have negative effects on mood and reduce one’s ability to cope with stress [53, 73]. Moreover, similar to epidemiological reports in youth from Canada and the USA [39, 61], adolescents in the current study reported spending more than 5 h per day in front of screens and engaged in only 30 min of physical activity per day. This excessive amount of ST could displace time spent engaging in physical activity, which has been shown to be protective against depression [37].

ST may also impact depressive symptoms through content of the media exposure, the situation, or the messages. For example, the association we found between computer use and depressive symptoms could have been due to youth repeatedly comparing themselves to idealized but unattainable images [36, 41, 72]. Relatedly, research has shown that high Internet use is associated with depression, with possible mechanisms of weakened family communication and social ties [34, 64, 78]. Moreover, social networking, which may have comprised a large proportion of time spent on computer use in the current study, has been associated with a myriad of negative mental health outcomes, including depression [54]. Although a review by Livingstone and colleagues [42] indicated that communication by the Internet may be a healthy way for some young people to meet social needs, it can be particularly problematic for those already isolated or marginalized, which is often the case with overweight and obese youth who comprised the present sample [60]. Video games may be associated with depression through social isolation, unfavorable comparisons to unrealistic images, frequent losing to other gamers, or the aggressive or negative content of the games themselves [31, 36]. However, video games have also been shown to be a distraction from stress due to high attentional demands, a source of enjoyment, and stimulates a release of dopamine [32], the neurochemical that mediates one’s sense of pleasure and reward, which may explain why some studies showed video gaming was inversely associated with depressive symptoms [11, 50]. Our finding that TV viewing was not associated with depressive symptoms may be explained by the possibility that much of the TV viewing may have occurred with other family members, allowing social interaction, unlike computer use and video games which tend to be more solitary. Moreover, the nature and context and content of TV viewing (i.e., how teens watch, what they watch, and with whom), which were beyond the scope of this study, may be more important than simply the number of hours watched [45]. It is important to note, however, that the null association between TV viewing and depressive symptoms should be interpreted with caution given the trend (p = 0.09) almost reached statistical significance, and the null association may have been partially due to the fact that all three screen behaviors were entered into the regression analyses as we wanted to determine which were the strongest predictors. Thus, future research is needed to clarify the relationship between TV viewing and depression in overweight and obese youth.

It is important to note that most studies have been cross-sectional, thus directionality of the screen time and depression relationships cannot be ascertained. While one longitudinal study showed that screen time predicted depression in adolescents [59], there is also prospective data indicating depressive symptoms predicted elevated screen time usage [29]. Although these studies did not control for physical activity and other important confounders, the findings highlight the potential for reciprocal relationships whereby excessive screen time may lead to or exacerbate feelings of depression, and those who feel depressed may spend more time indoors and in front of screens, further socially isolating themselves and exposing them to content or messaging that depresses their mood, creating a vicious cycle.

Given adolescent girls are at higher risk of depression than boys [13, 56], we explored the possibility of sex differences in the relationship between screen time and depression. Although the results of the screen time by sex interactions were not significant, indicating the relationship between the screen time and depressive symptoms did not differ between boys and girls, our sample was comprised primarily of girls. Thus, it is possible we did not have adequate statistical power to properly evaluate sex differences. The sparse literature in this area in normal-weight youth has shown mixed findings, with one study showing a relationship between screen time and depressive symptoms in girls but not boys [66], while another found the relationship in adolescent boys but not girls [67]. The paucity of research in this area, combined with the mixed findings in the initial studies, underscores the need to further examine if the relationship between screen time and depressive symptoms differs by sex, and whether weight status (normal weight vs overweight/obese) moderates this relationship.

Limitations and strengths

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences about ST and depression, and it is possible that youth who feel depressed spend more time indoors and engaged in more ST [29], which may exacerbate their depressed mood. In addition, physical activity was a covariate and measured by self-report, consistent with most of the previous studies, so future studies should use objective measures (i.e., accelerometry) for more accurate measurement. However, given physical activity is often overestimated when measured by self-report compared to objective measurement [19], and our associations between screen time and depressive symptoms remained after controlling for physical activity, obtained effects may actually be conservative. As with most work on ST behavior, this measurement was obtained by self-report, thus there is the possibility of measurement error; however, results from a recent systematic review have shown that children and youth under-report sedentary behavior [1]. Finally, there is also the possibility of response bias due to the fact that participants were recruited by responding to community advertisements; as a result, it is unclear whether these findings can be generalized to all overweight and obese adolescents in the community. The present study also has several strengths. These include using a well validated measure of depressive symptoms in children and youth, and assessment of three specific forms of ST (TV, video games, and recreational computer use) which was not always included in previous studies. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between duration and type of ST and depression in a sample of overweight and obese adolescents, which is clinically relevant given this population is at increased risk of depression [63] and spend disproportionately more time in front of screens compared to normal-weight youth [70]. Finally, the current study included a comprehensive set of covariates that controlled for many important confounders, strengthening the internal validity of the findings.

Conclusions

The present study found that overall exposure to ST, particularly time spent engaged in video games and recreational computer use, were associated with more severe depressive symptomatology in a sample of overweight and obese adolescents after controlling for a wide range of confounders. These finds suggest that excessive ST may represent a risk factor or behavioral marker for depressive symptomatology in overweight and obese youth. Thus, youth presenting for treatment for depression should be screened for excessive ST usage, especially if overweight or obese. While targeting reductions in ST are critical components of pediatric obesity treatment and prevention [20], future randomized controlled trials are needed to determine whether reductions in ST attenuate depressive symptoms in overweight or obese youth. These studies would be especially important given that obese youth report more severe depressive symptoms compared to their normal-weight peers [23] which may be due, in part, to the widespread weight-based teasing and bullying [16] and discrimination and bias they commonly experience in society [60].

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDI:

-

Children’s depression inventory

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- ST:

-

Screen time

References

Adamo KB, Prince SA, Tricco AC, Connor-Gorber S, Tremblay M (2009) A comparison of indirect versus direct measures for assessing physical activity in the pediatric population: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Obes 4:2–27

Alberga AS, Goldfield GS, Kenny GP, Hadjiyannakis S, Phillips P, Prud’homme D, Tulloch H, Gougeon R, Wells GA, Sigal RJ (2012) Healthy Eating, Aerobic and Resistance Training in Youth (HEARTY): study rationale, design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials 33:839–847

Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Bartlett SJ, Cheskin LJ, Pratt M (1998) Relationship of physical activity and television watching with body weight and level of fatness among children: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA 279:938–942

Government of Australia (2004) Australia’s physical activity recommendations for 12–18 year olds. Department of Health and Ageing. Canberra, Australia

Bertha EA, Balazs J (2013) Subthreshold depression in adolescence: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22:589–603

Active Healthy Kids Canada (2012) is active play extinct? The Active Healthy Kids Canada Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. Active Healthy Kids Canada, Toronto

Active Healthy Kids Canada (2013) Are we driving our kids to unhealthy habits? Active Healthy kids Canada Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. Active Healthy Kids Canada, Toronto

Statistics Canada (2003) National longitudinal survey of children and youth. Human Resources Development Canada and Statistics Canada

Cao H, Qian Q, Weng T, Yuan C, Sun Y, Wang H, Tao F (2011) Screen time, physical activity and mental health among urban adolescents in China. Prev Med 53:316–320

Carson V, Janssen I (2011) Volume, patterns, and types of sedentary behavior and cardio-metabolic health in children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 11:274

Casiano H, Kinley DJ, Katz LY, Chartier MJ, Sareen J (2012) Media use and health outcomes in adolescents: findings from a nationally representative survey. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21:296–301

Chaput JP, Visby T, Nyby S, Klingenberg L, Gregersen NT, Tremblay A, Astrup A, Sjodin A (2011) Video game playing increases food intake in adolescents: a randomized crossover study. Am J Clin Nutr 93:1196–1203

Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK (2000) Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: a theoretical model. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:21–27

De Moor MH, Beem AL, Stubbe JH, Boomsma DI, De Geus EJ (2006) Regular exercise, anxiety, depression and personality: a population-based study. Prev Med 42:273–279

Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS (2002) Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet 360:473–482

Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M (2003) Associations of weight-based teasing and emotional well-being among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 157:733–738

Ekelund U, Brage S, Froberg K, Harro M, Anderssen SA, Sardinha LB, Riddoch C, Andersen LB (2006) TV viewing and physical activity are independently associated with metabolic risk in children: the European Youth Heart Study. PLoS Med 3:e488

Everson SA, Maty SC, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA (2002) Epidemiologic evidence for the relation between socioeconomic status and depression, obesity, and diabetes. J Psychosom Res 53:891–895

Garriguet D, Colley RC (2014) A comparison of self-reported leisure-time physical activity and measured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in adolescents and adults. Health Rep 25:3–11

Goldfield GS, Raynor H, Epstein L (2002) Treatment of pediatric obesity. In: Wadden T, Stunkard A (eds) Handbook of obesity treatment. Guilford Press, New York, pp 532–555

Goldfield GS, Henderson K, Buchholz A, Obeid N, Nguyen H, Flament MF (2011) Physical activity and psychological adjustment in adolescents. J Phys Act Health 8:157–163

Goldfield GS, Kenny GP, Hadjiyannakis S, Phillips P, Alberga AS, Saunders TJ, Tremblay MS, Malcolm J, Prud’homme D, Gougeon R, Sigal RJ (2011) Video game playing is independently associated with blood pressure and lipids in overweight and obese adolescents. PLoS One 6(11):e26643

Goldfield GS, Moore C, Henderson K, Buchholz A, Obeid N, Flament MF (2010) Body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint, depression, and weight status in adolescents. J Sch Health 80:186–192

Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH (1996) Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 150:356–362

Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW (2004) Exercise physiology versus inactivity physiology: an essential concept for understanding lipoprotein lipase regulation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 32:161–166

Hardy LL, Denney-Wilson E, Thrift AP, Okely AD, Baur LA (2010) Screen time and metabolic risk factors among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 164:643–649

Heponiemi T, Elovainio M, Kivimaki M, Pulkki L, Puttonen S, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L (2006) The longitudinal effects of social support and hostility on depressive tendencies. Soc Sci Med 63:1374–1382

Houghton S, Hunter SC, Rosenberg M, Wood L, Zadow C, Martin K, Shilton T (2015) Virtually impossible: limiting Australian children and adolescents daily screen based media use. BMC Public Health 15:5

Hume C, Timperio A, Veitch J, Salmon J, Crawford D, Ball K (2011) Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. J Phys Act Health 8:152–156

Jacka FN, Kremer PJ, Leslie ER, Berk M, Patton GC, Toumbourou JW, Williams JW (2010) Associations between diet quality and depressed mood in adolescents: results from the Australian Healthy Neighbourhoods Study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 44:435–442

Kappos AD (2007) The impact of electronic media on mental and somatic children’s health. Int J Hyg Environ Health 210:555–562

Koepp MJ, Gunn RN, Lawrence AD, Cunningham VJ, Dagher A, Jones T, Brooks DJ, Bench CJ, Grasby PM (1998) Evidence for striatal dopamine release during a video game. Nature 393:266–268

Kovacs M (1992) The children’s depression inventory (CDI) manual. Multi-Health Systems Inc., Toronto, p 15–25

Kraut R, Patterson M, Lundmark V, Kiesler S, Mukopadhyay T, Scherlis W (1998) Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am Psychol 53:1017–1031

Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL (2002) 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11:1–190

Lakdawalla Z, Hankin BL, Mermelstein R (2007) Cognitive theories of depression in children and adolescents: a conceptual and quantitative review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 10:1–24

Larun L, Nordheim LV, Ekeland E, Hagen KB, Heian F (2006) Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD004691

Leatherdale ST, Ahmed R (2011) Screen-based sedentary behaviours among a nationally representative sample of youth: are Canadian kids couch potatoes? Chronic Dis Inj Can 31:141–146

Leatherdale ST, Harvey A (2015) Examining communication- and media-based recreational sedentary behaviors among Canadian youth: results from the COMPASS study. Prev Med 74:74–80

Lemstra M, Neudorf C, D’Arcy C, Kunst A, Warren LM, Bennett NR (2008) A systematic review of depressed mood and anxiety by SES in youth aged 10–15 years. Can J Public Health 99:125–129

Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR (1998) Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev 18:765–794

Livingstone S, Bober M, Helsper E (eds) (2004) Active participation of just more information? Young people’s take up of opportunities to act and interact on the Internet. London School of Economics and Political Science, London

Maras D, Flament MF, Murray M, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, Goldfield GS (2015) Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev Med 73:133–138

Marshall SJ, Biddle SJ, Gorely T, Cameron N, Murdey I (2004) Relationships between media use, body fatness and physical activity in children and youth: a meta-analysis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28:1238–1246

Mathers M, Canterford L, Olds T, Hesketh K, Ridley K, Wake M (2009) Electronic media use and adolescent health and well-being: cross-sectional community study. Acad Pediatr 9:307–314

McHale SM, Crouter AC, Tucker CJ (2001) Free- time activities in middle childhood: links with adjustment in early adolescence. Child Dev 72:1764–1778

Merikangas K, Avenevoli S (2002) Epidemiology of mood and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. In: Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology, John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, p 657–702

Sedentary Behaviour Research Network SBRN (2012) Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms “sedentary” and “sedentary behaviors.”. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37:540–542

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM (2014) Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 311:806–814

Ohannessian CM (2009) Media use and adolescent psychological adjustment: an examination of gender differences. J Child Fam Stud 18:582–593

Oldham-Cooper RE, Hardman CA, Nicoll CE, Rogers PJ, Brunstrom JM (2011) Playing a computer game during lunch affects fullness, memory for lunch, and later snack intake. Am J Clin Nutr 93:308–313

World Health Organization (WHO) (2006) Constitution of the World Health Organization. Switzerland, Geneva, pp 1–18

Owens J, Maxim R, McGuinn M, Nobile C, Msall M, Alario A (1999) Television-viewing habits and sleep disturbance in school children. Pediatrics 104:e27

Pantic I, Damjanovic A, Todorovic J, Topalovic D, Bojovic-Jovic D, Ristic S, Pantic S (2012) Association between online social networking and depression in high school students: behavioral physiology viewpoint. Psychiatr Danub 24:90–93

American Academy of Pediatrics AAP (2013) Children, adolescents, and the media. In: statement AAoPP (ed), pp 958–961

Petersen AC, Sarigiani PA, Kennedy RE (1991) Adolescent depression: why more girls? J Youth Adolesc 20:247–271

Pine DS, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brook J (1999) Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: moodiness or mood disorder? Am J Psychiatry 156:133–135

Pratt L, Brody D (2008) Depression in the United States household population, 2005-2006. NCHS Data Brief 7:1–8

Primack BA, Swanier B, Georgiopoulos AM, Land SR, Fine MJ (2009) Association between media use in adolescence and depression in young adulthood: a longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:181–188

Puhl RM, Latner JD (2007) Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation’s children. Psychol Bull 133:557–580

Rideout V, Foehr U, Roberts D (2010) Generation M2 media in the lives of 8- to 18-Year Olds. In: Kaiser Family Foundation. http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf

Roberts KC, Shields M, de Groh M, Aziz A, Gilbert JA (2012) Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: results from the 2009 to 2011 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Rep 23:37–41

Roberts RE, Deleger S, Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA (2003) Prospective association between obesity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27:514–521

Sanders CE, Field TM, Diego M, Kaplan M (2000) The relationship of Internet use to depression and social isolation among adolescents. Adolescence 35:237–242

Santaliestra-Pasias AM, Mouratidou T, Verbestel V, Bammann K, Molnar D, Sieri S, Siani A, Veidebaum T, Marild S, Lissner L, Hadjigeorgiou C, Reisch L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Moreno LA (2014) Physical activity and sedentary behaviour in European children: the IDEFICS study. Public Health Nutr 17:2295–2306

Suchert V, Hanewinkel R, Isensee B (2015) Sedentary behavior, depressed affect, and indicators of mental well-being in adolescence: does the screen only matter for girls? J Adolesc 42:50–58

Sund AM, Larsson B, Wichstrom L (2011) Role of physical and sedentary activities in the development of depressive symptoms in early adolescence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46:431–441

Tremblay A, Sevigny J, Leblanc C, Bouchard C (1983) The reproducibility of a three-day dietary record. Nutr Res 3:819–830

Tremblay MS, Leblanc AG, Janssen I, Kho ME, Hicks A, Murumets K, Colley RC, Duggan M (2011) Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines for children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 36(59–64):65–71

Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, Saunders TJ, Larouche R, Colley RC, Goldfield G, Connor Gorber S (2011) Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8:98

Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2002) Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort differences on the children’s depression inventory: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 111:578–588

Van den Bulck J (2000) Is television bad for your health: behavior and body image of the adolescent “couch potato”. J Youth Adolesc 29:273–288

Van den Bulck J (2004) Television viewing, computer game playing, and Internet use and self-reported time to bed and time out of bed in secondary-school children. Sleep 27:101–104

Weston AT, Petosa R, Pate RR (1997) Validation of an instrument for measurement of physical activity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 29:138–143

Wiecha JL, Peterson KE, Ludwig DS, Kim J, Sobol A, Gortmaker SL (2006) When children eat what they watch: impact of television viewing on dietary intake in youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160:436–442

Wight RG, Sepulveda JE, Aneshensel CS (2004) Depressive symptoms: how do adolescents compare with adults? J Adolesc Health 34:314–323

Wurtman JJ (1990) Carbohydrate craving. Relationship between carbohydrate intake and disorders of mood Drugs 39(Suppl 3):49–52

Ybarra ML, Alexander C, Mitchell KJ (2005) Depressive symptomatology, youth Internet use, and online interactions: a national survey. J Adolesc Health 36:9–18

Acknowledgments

This is a sub-study of the Healthy Eating, Aerobic, and Resistance Training in Youth (HEARTY) Trial (Clinicaltrials.gov Registration: NCT00195858), which was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Gary S. Goldfield was supported by a Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) Volunteer Association Endowed Scholar Award and a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Marisa Murray, Danijela Maras, and Angela L. Wilson were supported by Ontario Graduate Scholarships. Dr. Alberga was supported by a Doctoral Student Research Award from the Canadian Diabetes Association and an “Eyes High” Postdoctoral Fellowship from the University of Calgary. Glen P. Kenny is supported by the University of Ottawa Research Chair. Ronald J. Sigal is supported by a Health Senior Scholar Award from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. The authors would like to thank all of the subjects who participated in the study and all the research staff who assisted with the data collection and implementation of the protocol.

Contributor’s statement

Gary S. Goldfield conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, contributed to the writing of the manuscript, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Marisa Murray, Danijela Maras, Angela L. Wilson, Jameason Cameron, and Heather Tulloch analyzed and interpreted the data, contributed to the writing of the manuscript, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Penny Phillips coordinated and supervised data collection, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Glen P. Kenny, Ronald J. Sigal, and Stasia Hadjiyannakis and Angela Alberga conceptualized and designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed written consent from each participant was obtained in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines for human subjects. In the case of minors under the age of 16 years, written consent was also obtained by parents or legal guardians. The current study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Boards of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) (protocol no. 05/04E) and The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (protocol no. 2004219-01H).

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

Data were collected as part of the Healthy Eating, Aerobic, and Resistance Training for Youth (HEARTY) trial (Clinicaltrials.gov Registration: NCT00195858), which was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number MCT-71979).

Financial disclosure statement

No financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Additional information

Communicated by Jaan Toelen

Revisions received: 29 January 2016; 21 March 2016; 15 March 2016

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goldfield, G.S., Murray, M., Maras, D. et al. Screen time is associated with depressive symptomatology among obese adolescents: a HEARTY study. Eur J Pediatr 175, 909–919 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2720-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2720-z