Abstract

To date, researchers have lacked a validated instrument to measure stroke caregivers’ satisfaction with hospital care. We adjusted a validated patient version of satisfaction with hospital care for stroke caregivers and tested the 11-item caregivers’ satisfaction with hospital care (C-SASC hospital scale) on caregivers of stroke patients admitted to nine stroke service facilities in the Netherlands. Stroke patients were identified through the stroke service facilities; caregivers were identified through the patients. We collected admission demographic data from the caregivers and gave them the C-SASC hospital scale. We tested the instrument by means of structural equation modeling and examined its validity and reliability. After the elimination of three items, the confirmatory factor analyses revealed good indices of fit with the resulting eight-item C-SASC hospital scale. Cronbach’s α was high (0.85) and correlations with general satisfaction items with hospital care ranged from 0.594 to 0.594 (convergent validity). No significant relations were found with health and quality of life (divergent validity). Such results indicate strong construct validity. We conclude that the C-SASC hospital scale is a promising instrument for measuring stroke caregivers’ satisfaction with hospital stroke care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interest in assessing caregivers’ (spouse, partner, child, sibling, etc.) satisfaction with the hospital care given to stroke victims—an important indicator of quality of care [1–6]—is increasing [1]. Caregivers are often dissatisfied [6], many citing a lack of communication about services the patient has received [7–9]. Caregiver well-being could be improved through in-hospital delivery of stroke care that meets their needs and demands which, in turn, could relieve caregiver stress.

Such state of dissatisfaction despite the importance of the caregivers’ role could be explained in part by the lack of a validated stroke-specific caregiver satisfaction measure. Since the Satisfaction with Stroke Care (SASC) Questionnaire (Appendix 1) is validated for stroke patients [3, 10–13], our study investigates its reliability and validity for caregivers after adjusting the original SASC hospital scale accordingly. We tested the resulting 11-item caregivers’ satisfaction with hospital care scale (C-SASC hospital scale; Appendix 2) on stroke patient caregivers in the Netherlands.

Methods

The study was conducted at nine stroke service facilities in the Netherlands [14]. Since the measurements of satisfaction with care were part of daily practice and were initiated and implemented by stroke service facilities and not the research team, no ethics approval was required. Access to subjects was granted by the management staff at each facility.

Subjects

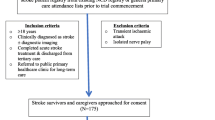

Stroke patients were identified through the stroke service facilities, and caregivers were identified through the participating stroke patients. Stroke patients who agreed to participate were asked to nominate their principal informal caregiver. This person was defined as “the person who helps you the most but who is not paid to do so.” Patients who were subsequently diagnosed with transient ischemic attack (TIA) instead of stroke were excluded, which led to an initial sample of 915 patients. Because 91 of these 915 stroke patients died during their hospital stay, the final sample consisted of caregivers of 824 patients.

Data collection and instrument assessment

We used demographic data that was collected by staff during hospital admission of the patient, which included gender, education, and relationship to the stroke patient (partner, child, sibling, other).

The original SASC for patients was validated by Boter and colleagues [1] in the Netherlands using forward and backward translation. We divided the first item of the original SASC, “I have been treated with kindness and respect by the staff at the hospital,” into two items to inquire about both the caregiver and the stroke patient. To obtain more information about satisfaction with the hospitalization process and hospital information received, we adjusted the SASC hospital scale and added two items. The resulting C-SASC hospital scale (Appendix 2) consists of 11 items measuring caregivers’ satisfaction with inpatient stroke care. Caregivers indicated their agreement with each item on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree); higher total scores indicate greater satisfaction [3].

Reliability of the instrument was assessed by determining the statistical coherence of the scaled items, which reflects the degree to which they measure the intended aspect of satisfaction. Validity is the degree to which a scale measures what it is intended to measure; here we focused on the construct validity of the questionnaire. Construct validity is supported if (1) instruments purported to assess the same concept (e.g., satisfaction) correlate substantially with one another (convergent validity) and (2) instruments purported to assess a different concept exhibit lower correlations (divergent validity). We evaluated construct validity by comparing the C-SASC hospital scale scores with caregivers’ reports (score of 1–10) on the staff’s attitude towards them and the extent to which their wishes had been taken into account (convergent validity). We evaluated divergent validity by correlating the overall C-SASC scores with those of stroke caregivers’ health and quality of life (QoL). We used the EuroQol questionnaire (EQ-5D) to measure the QoL of stroke caregivers, which uses a simple generic measure to aggregate QoL into a single index [15]. The EQ-5D comprises five questions about the current health state in five dimensions: mobility, self care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression [15, 16]. Responses collapse into one of three levels: no problems (score of 1), moderate problems (2), and extreme problems (3). To assess health of stroke caregivers the EQ-5D questionnaire was followed by a the visual analogue scale (VAS), a graph representation similar to a thermometer that ranges from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state) [16].

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to analyze the caregivers’ demographic characteristics. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine differences between demographic characteristics of stroke caregivers in relationship to SASC. Cronbach’s α served as a measure of homogeneity reflecting the (weighted) average correlation of items within a scale [17]. In general, reliability is considered to be good if α > 0.80. The construct correlation patterns (trough convergent and divergent validity) were calculated with Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

To verify the one factor structure of the 11 C-SASC hospital scale items and to seek relationships between observed variables and their underlying latent constructs, confirmatory factor analysis was performed twice using LISREL software [18] by (1) listwise deletion of items with missing responses and (2) replacing missing responses with mean values. The models were tested in LISREL with four indices of fit using the cutoff criteria proposed by Hu and Bentler [19]. First, the overall goodness-of-fit test assessed the discrepancy between the model and the sample covariance matrix by means of a normal-theory weighted least squares test. Plausible models had low, preferably non-significant, χ 2 values. Second, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) reflects the estimation error divided by the degrees of freedom as a penalty function. RMSEA values below 0.06 were taken to indicate small differences between the estimated and observed models. Third, we used the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), which is a scale-invariant index for global fit that ranges from 0 to 1. SRMR values lower than 0.08 were considered to indicate a good fit. Fourth, we calculated the incremental fit index (IFI), which compares the independent model (i.e., observed variables are unrelated) to the estimated model. We considered IFI values larger than 0.95 indicators of a good fit. If confirmatory analysis with the full model (11 items) did not meet the four indices proposed by Hu and Bentler [19], we were prepared to exclude items one by one, following the modification indices provided by LISREL and the strength of the loadings, until the cutoff criteria for the four indices were met.

Results

The response rate of the caregivers was 40% (332/824). A primary reason for non-response was the distribution of the questionnaire 1 day before the patient’s discharge, which sometimes did not allow enough time for completion.

Description of stroke patients’ caregivers

Most (65%) of the caregivers were female (Table 1). The majority (57%) were the patient’s partner, 38% his or her child, and 5% his or her sibling. We found no significant differences between caregivers’ relationship (F 0.760; p 0.796), gender (T 1.052; p 0.399), educational level (F 1.213; p 0.220) and satisfaction with care, as measured by the C-SASC hospital scale.

Confirmatory factor analysis with the 11-item C-SASC hospital scale

Standardized loadings of the 11 C-SASC hospital scale items are shown in Table 2 (results of the confirmatory analysis with listwise deletion of missing responses). The indices of model fit showed insufficiency (Table 3, model 1). The RMSEA value of the C-SASC was 0.10, which is well above the cutoff value of 0.06. The IFI of 0.97 met the cutoff criteria of >0.95, but the SRMR value of 0.13 exceeded the cutoff value of 0.08. These indices indicated that the model could be improved.

We ran the confirmatory factor analysis twice, first with listwise deletion of missing responses and second with mean values in the place of missing responses. The results of the first stepwise confirmatory factor analysis (listwise deletion) showed that the elimination of items 6, 8, and 11 produced a model with a globally sufficient fit, as indicated by an RMSEA value of 0.05 and an IFI value of 0.99 (Table 3, model 4). The Satorra–Bentler scaled χ 2 value was 31.02 and significant (p = 0.000), and the SRMR value was 0.08. This resulted in a final eight-item instrument (Appendix 2).

The second confirmatory factor analysis in which missing responses were replaced with mean values led to the same stepwise exclusion of items 6, 8, and 11. The results of the fourth model produced in this manner showed a globally sufficient fit, indicated by exactly the same values as the first confirmatory factor analysis and leading to the same final eight-item C-SASC hospital scale (Appendix 2).

Reliability and validity

The descriptive statistical index of the C-SASC hospital scale was 18 ± 3.1. Cronbach’s α was 0.85, indicating good reliability of the scale.

To estimate construct validity of the instrument (Table 4), we looked at correlations between staff attitude toward stroke caregivers (r = 0.594, p ≤ 0.001) and the extent to which their wishes had been taken into account (r = 0.593, p ≤ 0.001). These values indicated convergent validity. The relation between caregivers’ SASC and (1) their health (r = −0.010, p = 0.877) and (2) their QoL (r = 0.003, p = 0.965) indicated divergent validity.

Discussion

This study aimed to develop and validate an instrument to measure stroke caregivers’ satisfaction with hospital care. This is the first study to assess stroke caregivers’ satisfaction using a Dutch sample, and our results show that the C-SASC hospital scale is a reliable and valid instrument. Since we tested the translated Dutch version of the original SASC we recommend testing the English version in other countries to ensure international validity. The results of the confirmatory factor analyses revealed good indices of fit with the eight-item C-SASC hospital scale. As indicated by the high reliability coefficient the scale showed good internal consistency. We found support for convergent validity through high correlations between the C-SASC hospital scale and the two general satisfaction items. In addition, we found strong support for divergent validity, since we found no significant relationship between a stroke caregiver’s satisfaction with hospital care and his or her health and quality of life. Since the C-SASC correlated substantially with the two general satisfaction items and no significant relationship was found with health and QoL we can conclude the C-SASC showed strong construct validity.

Several psychometric properties could not be evaluated in this study and thus remain undefined. These include assessment of the instrument’s responsiveness, its predictive value (e.g., of caregiver well-being and patient QoL), and different modes of administration. More research is necessary to investigate the relations between severity of stroke, the patient’s QoL, and caregiver’s SASC. Since we excluded patients who died during hospital stay we could not investigate SASC of their caregivers. Not all items of the C-SASC were applicable for these caregivers. Future research is necessary to test an adjusted version of the C-SASC to assess their satisfaction with stroke care. The original SASC for patients consists of hospital and home subscales. We developed and validated the hospital scale for stroke caregivers and did not investigate the home scale. Further research is necessary to do so. In addition, we investigated the C-SASC before discharge which may have led to some bias on caregiver’s satisfaction with care compared to investigating satisfaction with care after discharge. Therefore, we recommend use of the C-SASC after discharge as well. With these shortcomings in mind, we conclude that the C-SASC hospital scale is a promising instrument for assessing stroke caregivers’ satisfaction with hospital care.

Notes

Items deleted after stepwise confirmatory factor analysis.

References

Boter H, de Haan RJ, Rinkel GLE (2003) Clinimetric evaluation of a Satisfaction-with Stroke-Care Questionnaire. J Neurol 250:534–541

Lewis JR (1994) Patients’ views on quality care in general practice: literature review. Soc Sci Med 39:655–670

Pound P, Gompertz P, Ebrahim S (1994) Patients’ satisfaction with stroke services. Clin Rehabil 8:7–17

van den Bos GAM, Limburg LCM (1995) Public health and chronic diseases. Eur J Pub Health 5:1–2

Larsen DE, Rootman I (1976) Physician role performance and patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med 10:29–32

Kincey J, Bradshaw P, Ley P (1975) Patients’ satisfaction and reported acceptance of advice in general practices. J R Coll Gen Pract 25:558–566

Hanger HC, Mulley GP (1993) Questions people ask about stroke. Stroke 24:536–538

Forster A, Smith J, Young J, Knapp P, House A, Wright J (2005) Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers. Cochrane Libr 5:1–74

van Veenedaal H, Grinspun DR, Adriaanse HP (1996) Educational needs of stroke patients and their family members, as perceived by themselves and by health professionals. Patient Educ Couns 28:256–276

Boter H (2004) Multicenter randomized controlled trial of an outreach nursing support program for recently discharged stroke patients. Stroke 35:2867–2872

Dennis M, O’Rourke S, Slatterly J, Staniforth T, Warlow C (1997) Evaluation of a stroke family care worker: results of a randomized controlled trial. BMJ 314:1071–1076

Gilbertson L, Langhorne P, Walker A, Allen A, Murray GD (2000) Domiciliary occupational therapy for patients with stroke discharged from hospitals: randomized controlled trial. BMJ 320:603–606

Rodgers H, Atkinson C, Bond S, Suddes M, Dobson R (1999) Randomized controlled trial of comprehensive stroke education program for patients and caregivers. Stroke 30:2585–2591

Nieboer A, Pepels R, Have L, van der Kool T, Huijsman R (2005) Stroke services gespiegeld, Hoofdrapport. ZonMW, Den Haag

EuroQol Group (1990) EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16:199–208

Brooks R (1996) EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 37:53–72

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Jöreskog K, Sörbom D (1996) User’s Reference Guide. Scientific Software International, Chicago

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6:1–55

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Patients’ satisfaction with inpatient stroke care (SASC hospital scale)

-

1.

I have been treated with kindness and respect by the staff at the hospital.

-

2.

The staff attended well to my personal needs while I was in hospital (for example, I was able to get to the toilet whenever I needed).

-

3.

I was able to talk to the staff about any problems I might have had.

-

4.

I have received all the information I want about the causes and nature of my illness.

-

5.

The doctors have done everything they can to make me well again.

-

6.

I am happy with the amount of recovery I have made.

-

7.

I am satisfied with the type of treatment the therapists have given me (e.g., physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy).

-

8.

I have had enough therapy (e.g., physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy).

Appendix 2: Caregivers’ satisfaction with inpatient stroke care (C-SASC hospital scale)

-

1.

I have been treated with kindness and respect by the staff at the hospital.

-

2.

The staff attended to my personal needs while I was in hospital and tried to support me as much as possible.

-

3.

I was able to talk to the staff about any problems I might have had.

-

4.

I received all the information I wanted about the causes and nature of the illness of the patient I take care of.

-

5.

The doctors did everything they could to make the patient I take care of well again.

-

6.

I am happy with the amount of recovery the patient I take care of has made.Footnote 1

-

7.

I am satisfied with the type of treatment the therapists have given the patient I take care of (e.g., physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy).

-

8.

The patient I take care of has had sufficient therapy (e.g., physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy) (See footnote 1).

-

9.

The patient I take care of has been treated with kindness and respect by the staff at the hospital.

-

10.

The hospitalization process went smoothly.

-

11.

I received all the information I wanted to about recovery and rehabilitation after a stroke (See footnote 1).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cramm, J.M., Strating, M.M.H. & Nieboer, A.P. Validation of the Caregivers’ Satisfaction with Stroke Care Questionnaire: C-SASC hospital scale. J Neurol 258, 1008–1012 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5871-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5871-2