Abstract

Having epilepsy has a large impact on one's well-being, but often seizure frequency and severity do not explain self-reported quality of life. We hypothesized that one's personal coping style is more important. In this study, 105 patients attending the outpatient neurological clinic at the University Medical Centre in Utrecht, the Netherlands, with a diagnosis of partial epilepsy, aged 17–80 years, completed questionnaires. Demographic information, disease characteristics, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and coping styles were obtained by postal-validated HRQoL questionnaires: the EQ5D and RAND-36 and the Utrecht Coping List. A passive coping style explained 45% of the variance in the mental component of HRQoL and was more important than ‘objective’ seizure-related measures. Confounders such as employment, gender, and side-effects of treatment explained another 6%. Passive coping style also influenced the physical component of the HRQoL, but here seizure-related factors predominated. Overall, epilepsy patients showed a more avoiding coping style, and female patients a less active coping style and more reassuring thoughts, compared to the Dutch population. The personal coping style of patients appears to be more important than seizure-related measures in predicting mental aspects of quality of life. Coping style characteristics rather than disease characteristics should guide clinical decision-making in patients with epilepsy. Further studies should investigate the effect on HRQoL of behavioral interventions to improve coping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epilepsy is a common disorder that has a great impact on people’s lives [1–4]. Patients experience social isolation, stigmatization, lack of understanding, and unemployment [5–8]. The risk of suicide is increased in patients with epilepsy [9]. There are also physical risks due to seizures, like falls, drowning, and burns and patients may feel insecure because seizures are unpredictable.

Health-related quality of Life (HRQoL) is an evaluation measure in treating patients with epilepsy. The impact of epilepsy on the HRQoL is generally assessed by mental status and seizure characteristics. Both influence HRQoL [10] but in clinical practice patients with similar clinical profiles show discrepant HRQoLs. We found the same paradox in caregivers: caring for intractable epilepsy affects their mental well-being, but the patients’ seizure frequency or severity did not explain the self-reported burden of care [4]. Having seizures or taking care of somebody with seizures leads to individualized responses and impact on HRQoL. This could be an expression of personal coping style, which is the person’s typical response when dealing with stressful life-events or smaller problems in daily life. The relation between personal coping strategy and HRQoL in other chronic diseases is well established [11–14]. Patients’ coping styles differ from the general population [15, 16]. Patients with epilepsy may also show different coping styles. Earlier studies suggested a relationship between coping styles, self-perceived seizure severity, and well-being [17–20].

We hypothesized that coping style rather than disease characteristics determine HRQoL in epilepsy and wondered if patients with epilepsy have different coping styles than the general population.

Methods

Subjects

Selected patients attended the outpatient neurological clinic at the University Medical Centre in Utrecht, the Netherlands, since January 2007. This is a teaching hospital and a secondary and tertiary referral center for epilepsy, and has epilepsy surgery facilities. Inclusion criteria were: a diagnosis of partial epilepsy, an age between 16 and 80, an IQ higher than 80, a normal neurological examination and the ability to complete a Dutch questionnaire. Exclusion criteria were: the presence of a malignancy, stroke, or any other disorder with chronic neurological deficit. The study was approved by the hospital’s Medical Ethics Committee.

Questionnaires

A questionnaire was sent, after the patients’ approval. Data were obtained on gender, age, marital status (married, cohabiting, not cohabiting, single), employment (paid employment, unemployed, disabled, student, domestic work, volunteer work), epileptic treatment, side-effects of treatment (drowsiness, dizziness, irritable, skin eruption, combination or other) and average seizure frequency per month during the last 2 years. This seizure frequency was assessed primarily by number of seizures during the last 2 years, but checked by two questions about how many minor or major seizures occurred in the last month, as well as the date of the last seizure. Inconsistent answers on seizure frequency counted as missing values. Finally, we asked whether the patient experienced epilepsy as his or her most important (neurological) medical problem, to verify the inclusion. HRQoL was assessed by generic questionnaires: the EQ-5D and the RAND-36 (SF-36) [21, 22]. The EQ-5D consists of five questions on five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). The answers can be translated into a utility value describing the respondent’s health state, ranging from zero (death) to one (perfect health). The RAND-36 consists of 36 questions and gives HRQOL-scores on eight domains (minimum 0, optimum 100) and two summary scores, the mental (MCS) and physical component scores (PCS) of HRQoL. Coping style was measured using the Utrecht Coping List (UCL), providing coping style profiles [23, 24]. This is a validated questionnaire that quantifies coping style characteristics for problems and unpleasant events in daily life. Patients have to respond to the question ‘how often do the following behaviors apply to you?’ by ticking ‘never’ (1 point) to ‘very often’ (4 points). Subscores were used to describe individual tendency to seven coping strategies: passive reaction pattern (seven items), active confronting (seven items), palliative reaction (eight items), seeking social support (six items), avoidance (eight items), expressing emotions (three items) and reassuring thoughts (five items). A high score indicates an increased tendency towards using a specific coping strategy. The UCL is based on the premise that coping strategies are not mutually exclusive and may be used in various combinations.

Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS v15.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA). Means and median (range) values were used to describe patient characteristics with normal and skewed distributions. Gender and age of responders and non-responders were compared using, respectively, a Chi-square test and a Mann–Whitney U test. Ages were equally represented.

EQ5D utility scores, domain and summary scores of the RAND-36 and the UCL coping styles were calculated and compared to the Dutch population using a two-tailed independent t test [21, 22, 24]. The reference population for the RAND-36 was aged between 16 and 94 years (mean 47.6 years) and for the EQ5D, above 16 years.

We explored the association between coping styles and the HRQoL-outcome measures PCS and MCS using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Subsequently, the coping style that had the strongest association with HRQoL was studied in a multivariate regression analysis.

We studied the association of patient characteristics, i.e., age, gender, partner (yes, no), paid employment (yes, no) and disease characteristics (age of onset, duration of epilepsy, seizure frequency, number of antiepileptic drugs, epilepsy surgery, epilepsy as most important problem) with the MCS and PCS by univariate linear regression analysis, using a cut-off p value of 0.20. Subsequently, parameters with a p value below the cut-off value were entered in a stepwise backwards multivariate linear regression analysis, including passive coping style, with MCS or PCS as the dependent variable to study independent effects of coping style and patient characteristics on HRQoL.

Results

Subjects

Out of 362 patients with the diagnosis of partial epilepsy, 177 were eligible, of whom 105 (59%) responded and were finally included in the study. Responders were more likely to be female (58 vs. 43%, p = 0.049) and slightly older (44.4 vs. 38.8 years, p = 0.031) than nonresponders. Demographic and epilepsy characteristics of the responders are presented in Table 1.

Quality of life

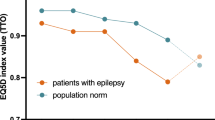

The average EQ5D utility score of the patients was 0.80, which is 9.2% lower than in the Dutch population (p < 0.01) [21].

Figure 1 shows the absolute difference between the patients and the Dutch population in the eight domains and the summary scores of the RAND-36. RAND-36 scores of patients were significantly lower on the mental domains: social functioning (−12 points), vitality (−12 points), role-emotional (−20), and general health (−11 points) and the physical domain: role physical (−20 points). This last domain describes experienced physical restrictions in reaching goals in life. The overall MCS was six points lower than the MCS of the normal population (p < 0.01).

RAND-36 summary scores and scores on eight domains in patients expressed as deviation, from the mean of the Dutch population (represented as zero) [21]. Positive scores represent better scores. *p < 0.01

Coping

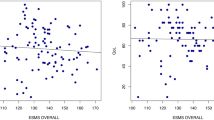

As shown in Table 2, patients used mainly palliative reaction patterns, active confronting, and avoidance. When compared to the reference population, avoidance was more prevalent in both male and female patients, and in female patients reassuring thoughts were more prevalent and active confronting less prevalent. Low MCS is strongly related to a passive coping strategy (Table 2; Fig. 2), as is, to a much lesser extent, to a lower PCS.

Patients and disease characteristics, coping, and QoL

Gender, paid employment, and side-effects of antiepileptic drugs were related to the MCS in the univariate analysis (p < 0.20, Table 3). In this univariate analysis, a passive coping style explained 45% of the variance in the MCS of HRQoL (adjusted R 2, 0.45), while the full model with passive coping style, gender, employment, and side-effects had an adjusted R 2 of 0.51, suggesting that these parameters explained only an additional variation of about 6% of the MCS. For the PCS, more factors were important: age, employment, seizure frequency, age of onset, experiencing epilepsy as most important problem, number of antiepileptic drugs, the presence of side-effects and a passive coping style. A passive coping style explains only 5% of the PCS; employment and age of onset seem to be as important.

Discussion

Individual coping style is more important to the lives of patients with focal epilepsy than ‘objective’ seizure-related facts. A passive coping style is highly correlated with a lower mental component of HRQoL and explains 45% of its variance: coping style is even important for the physical component of HRQoL, though seizure- and epilepsy-related factors play a more important role here. Patients with epilepsy show a coping profile different from the Dutch population.

This is the first study showing an important relationship between individual coping style and quality of life in patients with epilepsy. Although the design does not permit conclusions on causality, these results are important for patient-oriented care, especially when seizures are intractable.

Results were obtained in patients with normal IQ and partial epilepsy. Maybe results would have been different in patients with generalized epilepsies and in the mentally retarded. The latter group is especially difficult to investigate, and requires a different approach with more observational data. We chose to perform the study in patients with partial epilepsy because more patients would have intractable seizures, so any impact of ongoing seizures would be more evident.

Patients attended a secondary and tertiary outpatient’s clinic, with a relatively high percentage of surgical candidates. In the Netherlands, adult epilepsy is usually treated by neurologists, and almost all neurologists are hospital-based. Overall, the percentage of seizure-free patients will be larger in most other hospitals and in these patients the effect of coping may become mitigated. However, our study population may also be biased towards assertive and goal-seeking personality traits, and this would imply that in the general epilepsy population with seizures coping styles might be even more skewed towards the passive.

We do not know to what extent our findings may be culturally determined. In the Netherlands, the level of social security is high compared to other countries, and people receiving healthcare may cope more passively. Nevertheless, the relationship between passive coping style and HRQoL seems strong, and results on the HRQoL questionnaires are similar to those from other Western countries with less social security.

Depression was not taken into account in this study. We assume that a low MCS would translate into different degrees of depressive symptoms on depression scales. High scores on depression scales are known to correlate with HRQoL in epilepsy patients [25]. Considering coping style and depression, we enter more complicated psychological territory. It is likely that questionnaires measuring aspects of depressive behavior partly measure the same behavior investigated with questionnaires on coping style. Research on emotional coping shows this confounding [26, 27]. We thus expect a relationship between depression and coping style. Further research is needed to investigate the role of depressive symptoms in the coping of epilepsy patients.

The RAND-36 en EQ-5D scores are comparable to other studies in patients with epilepsy [28–31]. Reports on the impact of demographic and epilepsy characteristics on HRQoL show wide variation between different studies. Generally, none of the seizure-related factors explain much of the difference in quality of life in epilepsy [10, 32, 33]. A study on QoL and epilepsy showed depression and employment to be mutually correlated with an impact on QoL [32]. Depression, as pointed out, may be a translation of low MCS and thus be interdependent.

There are other diseases in which a passive coping style is associated with HRQoL. For example, in patients who had had a subarachnoid hemorrhage, passive coping style was associated with lower scores on the cognitive domain in the HRQoL [11].

This study reminds us that medical care for epilepsy patients should be highly individualized. Seizure calendars, while showing disease activity, do not reflect a patient’s well-being. Most studies on the effects of (drug) therapy ignore the fact that reduction of number of seizures and seizure severity may not translate into equal improvement in mental HRQoL. In fact, only cure from epilepsy, i.e., prolonged absolute seizure freedom, seems to influence QoL [34]. This underscores the fact that it is the unpredictability of seizures and a chronic, existential feeling of insecurity that poses the main burden in this disease. In a typical patient, the seizures themselves are only passing short-lived events. It is the constant awareness of what might happen, which makes epilepsy a chronic disease of the mind, especially in those who cannot cope with this mental stress. This is probably different from other chronic disease with more permanent manifestations such as arthritis or Parkinson’s disease. We believe that our findings press for different attitudes in therapeutic decision-making. In deciding about medication change or in considering epilepsy surgery, physicians have to balance risks versus potential benefit. Generally, physicians will rely on ‘objective’ measures to estimate seizure risk, i.e., seizure frequency, circumstances (e.g., occurrence during daytime or during sleep), and accidents. Our study shows how physician-centered this approach is. A true patient-oriented approach would take the coping capabilities of the individual patient as the most important risk factor. Thus, proceeding towards epilepsy surgery turns out much more logical in a patient with passive coping style and low scores on mental well-being, in spite of the fact that this patient may have only nocturnal seizures once a month.

More research is needed to understand the different coping profiles between patients and the general population. If coping style does not predispose for epilepsy, we speculate that some patients may have changed coping behavior in the course of their epilepsy. If true, this must encourage development of training programs to encourage more effective coping styles. Constructive coping strategies will enhance adjustment to chronic disease and improve HRQoL [35]. Interventions should then be tested for their efficacy and for their potential to improve HRQoL in patients with epilepsy.

Appendix: passive coping style | Seldom or never | Sometimes | Often | Very often |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Withdrawing yourself completely from others | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Being discouraged by a situation | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Being troubled about the past | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Using tranquilizers in situations of tension or nervousness | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Escaping in fantasies | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Being completely overwhelmed by problems | □ | □ | □ | □ |

Not being able to do anything | □ | □ | □ | □ |

References

Forsgren L, Beghi E, Oun A et al (2005) The epidemiology of epilepsy in Europe—a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 12:245–253

Strine TW, Kobau R, Chapman DP et al (2005) Psychological distress, comorbidities, and health behaviors among US adults with seizures: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. Epilepsia 46:1133–1139

Baker GA, Jacoby A, Buck D et al (1997) Quality of life of people with epilepsy: a European study. Epilepsia 38:353–362

van Andel J, Zijlmans M, Fischer K et al (2009) Quality of life of caregivers of patients with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia 50:1294–1296

Raty LK, Wilde Larsson BM (2007) Quality of life in young adults with uncomplicated epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 10:142–147

Olsson I, Campenhausen G (1993) Social adjustment in young adults with absence epilepsies. Epilepsia 34:846–851

Jacoby A (2008) Epilepsy and stigma: an update and critical review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 8:339–344

Smeets VM, van Lierop BA, Vanhoutvin JP et al (2007) Epilepsy and employment: literature review. Epilepsy Behav 10:354–362

Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Mortensen PB et al (2007) Epilepsy and risk of suicide: a population-based case-control study. Lancet Neurol 6:693–698

Jacoby A, Baker GA (2008) Quality-of-life trajectories in epilepsy: a review of the literature. Epilepsy Behav 12:557–571

Visser-Meily JM, Rhebergen ML, Rinkel GJ et al (2009) Long-term health-related quality of life after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: relationship with psychological symptoms and personality characteristics. Stroke 40:1526–1529

Siniatchkin M, Riabus M, Hasenbring M (1999) Coping styles of headache sufferers. Cephalalgia 19:165–173

Frazier LD (2000) Coping with disease-related stressors in Parkinson’s disease. Gerontologist 40:53–63

Finset A, Andersson S (2000) Coping strategies in patients with acquired brain injury: relationships between coping, apathy, depression and lesion location. Brain Inj 14:887–905

Kok ET, Bohnen AM, Bosch JL et al (2006) Patient’s quality of life and coping style influence general practitioner’s management in men with lower urinary tract symptoms: the Krimpen Study. Qual Life Res 15:1335–1343

Telles-Correia D, Barbosa A, Mega I et al (2009) Importance of depression and active coping in liver transplant candidates’ quality of life. Prog Transplant 19:85–89

Oosterhuis A (1999) Coping with epilepsy: the effect of coping styles on self-perceived seizure severity and psychological complaints. Seizure 8:93–96

Livneh H, Wilson LM, Duchesneau A et al (2001) Psychosocial adaptation to epilepsy: the role of coping strategies. Epilepsy Behav 2:533–544

Goldstein LH, Holland L, Soteriou H et al (2005) Illness representations, coping styles and mood in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 67:1–11

Cramer JA, Blum D, Reed M et al (2003) Epilepsy Impact Project Group. The influence of comorbid depression on seizure severity. Epilepsia 44:1578–1584

Hoeymans N, van Lindert H, Westert GP (2005) The health status of the Dutch population as assessed by the EQ-6D. Qual Life Res 14:655–663

Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD et al (1998) Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 51:1055–1068

Eriksen HR, Olff M, Ursin H (1997) The CODE: a revised battery for coping and defense and its relations to subjective health. Scand J Psychol 38:175–182

Schreurs PJG, van de Willige G, Tellegen B et al (1988) Handleiding Utrechtse Coping Lijst: UCL. Swets en Zeitlinger, Lisse

Kwan P, Yu E, Leung H, Leon T, Mychaskiw MA (2009) Association of subjective anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance with quality-of-life ratings in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia 50(5):1059–1066

Stanton AL, Noff-Burg S, Cameron CL et al (1994) Coping through emotional approach: problems of conceptualization and confounding. J Pers Soc Psychol 66:350–362

Stanton AL, Kirk SB, Cameron CL et al (2000) Coping through emotional approach: scale construction and validation. J Pers Soc Psychol 78:1150–1169

Wiebe S, Matijevic S, Eliasziw M et al (2002) Clinically important change in quality of life in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 73:116–120

de Weerd A, de Haas S, Otte A et al (2004) Subjective sleep disturbance in patients with partial epilepsy: a questionnaire-based study on prevalence and impact on quality of life. Epilepsia 45:1397–1404

Stavem K, Bjornaes H, Lossius MI (2001) Properties of the 15D and EQ-5D utility measures in a community sample of people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 44:179–189

Stavem K, Lossius MI, Kvien TK et al (2000) The health-related quality of life of patients with epilepsy compared with angina pectoris, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qual Life Res 9:865–871

Canuet L, Ishii R, Iwase M et al (2009) Factors associated with impaired quality of life in younger and older adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 83:58–65

Koponen A, Seppala U, Eriksson K et al (2007) Social functioning and psychological well-being of 347 young adults with epilepsy only–population-based, controlled study from Finland. Epilepsia 48:907–912

Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP et al (2001) A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med 345:311–318

de Ridder D, Geenen R, Kuijer R et al (2008) Psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Lancet 372:246–255

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients who participated in this study. We confirm that we have read the journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines. Maeike Zijlmans received grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) AGIKO-grant no. 92003481, the University Medical Center Utrecht (internationalization grant), and the ‘‘Stichting de drie lichten’’. Frans Leijten received a grant from the Dutch National Epilepsy Foundation (08-11-2009).

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Westerhuis, W., Zijlmans, M., Fischer, K. et al. Coping style and quality of life in patients with epilepsy: a cross-sectional study. J Neurol 258, 37–43 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5677-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5677-2