Abstract

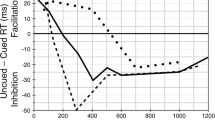

A review of traditional research on preparation and foreperiod has identified strategic (endogenous) and automatic (exogenous) factors probably involved in endogenous temporal-orienting experiments, such as the type of task, the way by which temporal expectancy is manipulated, the probability of target occurrence and automatic sequential effects, yet their combined impact had not been investigated. These factors were manipulated within the same temporal-orienting procedure, in which a temporal cue indicated that the target could appear after an interval of either 400 or 1,400 ms. We observed faster reaction times for validly versus invalidly cued targets, that is, endogenous temporal-orienting effects. The main results were that the probability of target occurrence (catch-trial proportion) modulated temporal orienting, such that the attentional effects at the short interval were independent of catch trials, whereas at the long interval the effects were only observed when catch trials were present. In contrast, the interval duration of the previous trial (i.e., exogenous sequential effects) did not influence endogenous temporal orienting. A flexible and endogenous mechanism of attentional orienting in time can account for these results. Despite the contribution of other factors, the use of predictive temporal cues was sufficient to yield attentional facilitation based on temporal expectancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the experiments reviewed here, the foreperiod durations usually ranged from 0.5 to 16 s.

Although the strategic view could also account for sequential effects, we will consider here sequential effects as an automatic contribution to temporal orienting effects, in order to further isolate the endogenous contribution of other strategic factors, such as the role of predictive temporal cues.

Data from four groups of the discrimination task (within-blocks and between-blocks groups by the 0 and 25% catch trial groups) were already reported in a previous article (Correa et al. 2004).

The medium SOA data were not included in the analyses due to insufficient observations in some experimental conditions (e.g., in the 50% catch trials group). The medium SOA has been previously used to make trend analyses in the RT function, in order to explore whether the attentional resources are assigned to specific moments in time in a gradual manner. Hence, the medium SOA did not provide relevant information for the purposes of the present study.

The manipulation of the between-subjects factors (e.g., the task) did not reverse the cue validity effects, rather it modulated the size of the effect (see results above, and also Correa et al. 2004). Thus, the analysis by combining the groups did not qualitatively change the main results.

References

Alegria J (1975) Sequential effects of foreperiod duration: Some strategical factors in tasks involving time uncertainty In: Rabbitt P, Dornic S (eds) Attention and performance V. Academic Press, London

Baumeister A, Joubert C (1969) Interactive effects on reaction time of preparatory interval length and preparatory interval frequency. J Exp Psychol 82:393–395

Bertelson P (1967) The time course of preparation. Q J Exp Psychol 19:272–279

Brown SW (1985) Time perception and attention: the effects of prospective versus retrospective paradigms and task demands on perceived duration. Percept Psychophys 38:115–124

Correa Á, Lupiáñez J, Milliken B, Tudela P (2004) Endogenous temporal orienting of attention in detection and discrimination tasks. Percept Psychophys 66:264–278

Correa Á, Lupiáñez J, Tudela P (2005) Attentional preparation based on temporal expectancy modulates processing at the perceptual-level. Psychon Bull and Rev 12:328–334

Coull JT, Frith CD, Buchel C, Nobre AC (2000) Orienting attention in time: Behavioural and neuroanatomical distinction between exogenous and endogenous shifts. Neuropsychologia 38:808–819

Coull JT, Nobre AC (1998) Where and when to pay attention: the neural systems for directing attention to spatial locations and to time intervals as revealed by both PET and fMRI. J Neurosci 18:7426–7435

Doherty JR, Rao A, Mesulam MM, Nobre AC (2005) Synergistic effect of combined temporal and spatial expectations on visual attention. J Neurosci 25:8259–8266

Drazin DH (1961) Effects of foreperiod, foreperiod variability, and probability of stimulus occurrence on simple reaction time. J Exp Psychol 62:43–50

Elithorn A, Lawrence C (1955) Central inhibition: Some refractory observations. Q J Exp Psychol 11:211–220

Gibbon J, Church RM, Meck WH (1984) Scalar timing in memory. In: Gibbon J, Allan L (eds) Timing and time perception. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, New York

Granjon M, Reynard G (1977) Effect of the length of the runs of repetitions on the simple RT-ISI relationship. Q J Exp Psychol 29:283–295

Griffin IC, Miniussi C, Nobre AC (2001) Orienting attention in time. Front Biosci 6:660–671

Griffin IC, Miniussi C, Nobre AC (2002) Multiple mechanisms of selective attention: differential modulation of stimulus processing by attention to space of time. Neuropsychologia 40: 2325–2340

James W (1890) The principles of psychology. Henry Holt, New York

Jones MR, Moynihan H, MacKenzie N, Puente J (2002) Temporal aspects of stimulus-driven attending in dynamic arrays. Psychol Sci 13:313–319

Karlin L (1959) Reaction time as a function of foreperiod duration and variability. J Exp Psychol 58:185–191

Kingstone A (1992) Combining expectancies. Q J Exp Psychol 44:69–104

Klemmer ET (1956) Time uncertainty in simple reaction time. J Exp Psychol 51:179–184

Los SA, Van den Heuvel CE (2001) Intentional and unintentional contributions to nonspecific preparation during reaction time foreperiods. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 27:370–386

Loveless NE, Sandford AJ (1974) Slow potential correlates of preparatory set. Biol Psychol 1:303–314

Milliken B, Lupiáñez J, Roberts M, Stevanovski B (2003) Orienting in space and time: Joint contributions to exogenous spatial cuing effects. Psychon Bull Rev 10:877–883

Miniussi C, Wilding EL, Coull JT, Nobre AC (1999) Orienting attention in time: modulation of brain potentials. Brain 122:1507–1518

Müller HJ, Rabbitt PM (1989) Reflexive and voluntary orienting of visual attention: time course of activation and resistance to interruption. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 15:315–330

Näätänen R (1972) Time uncertainty and occurrence uncertainty of the stimulus in a simple reaction time task. Acta Psychol 36:492–503

Niemi P, Näätänen R (1981) Foreperiod and simple reaction time. Psychol Bull 89:133–162

Nobre AC (2001) Orienting attention to instants in time. Neuropsychologia 39:1317–1328

Posner MI, Snyder CRR, Davidson BJ (1980) Attention and the detection of signals. J Exp Psychol: General 109:160–174

Schneider W (1988) Micro experimental laboratory: an integrated system for IBM PC compatibles. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 20:206–271

Walter WG, Cooper R, Aldridge VJ, McCallum WC, Winter AL (1964) Contingent negative variation: an electrical sign of sensorimotor association and expectancy in the human brain. Nature 203:380–384

Woodrow H (1914) The measurement of attention. Psychol Monogr 17:1–158

Zahn TP, Rosenthal D (1966) Simple reaction time as a function of the relative frequency of the preparatory interval. J Experimental Psychol 72:15–19

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Cultura with a predoctoral grant (FPU-AP2000-3167) to the first author, and research grants to Juan Lupiáñez (MCyT, BSO2002-04308-C02-02) and Pío Tudela (MCyT, BSO2003-07292). Please, address correspondence about this article either to Ángel Correa (act@ugr.es) or to Juan Lupiáñez (jlupiane@ugr.es), both at the University of Granada, Departamento de Psicología Experimental, Facultad de Psicología, Campus de Cartuja S/N, 18071 – Granada (Spain).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Correa, Á., Lupiáñez, J. & Tudela, P. The attentional mechanism of temporal orienting: determinants and attributes. Exp Brain Res 169, 58–68 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-005-0131-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-005-0131-x