Abstract

Purpose

Severe critical illness requiring treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU) may have a serious impact on patients and their families. However, optimal follow-up periods are not defined and data on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) before ICU admission as well as those beyond 2 years follow-up are limited. The aim of our study was to assess the impact of ICU stay up to 5 years after ICU discharge.

Methods

We performed a long-term prospective cohort study in patients admitted for longer than 48 h in a medical-surgical ICU. The Short-Form 36 was used to evaluate HRQOL before admission (by proxy within 48 h after admission of the patient), at ICU discharge, and at 1, 2, and 5 years following ICU discharge (all by patients). Changes in HRQOL were assessed using linear mixed modeling.

Results

We included a total of 749 patients (from 2000 to 2007). At 5 years after ICU discharge 234 patients could be evaluated. After correction for natural decline in HRQOL, the mean scores of four dimensions—physical functioning (p < 0.001), role-physical (p < 0.001), general health (p < 0.001), and social functioning (p = 0.003)—were still significantly lower 5 years after ICU discharge compared with their pre-admission levels, although effect sizes were small (<0.5).

Conclusions

After correction for natural decline, the effect sizes of decreases in HRQOL were small, suggesting that patients regain their age-specific HRQOL 5 years after their ICU stay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients treated in the intensive care unit (ICU) are the most critically ill patients within the hospital walls. Consequently, mortality in the first year after ICU discharge is high and it is suggested that there is an ongoing mortality and morbidity related to the critical illness for a period of up to 15 years after ICU discharge [1–6]. Although health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is a relevant outcome measure for patients admitted to the ICU, it is not routinely included in ICU practice or research. This may be because measuring HRQOL is more time-consuming than mortality rates and is also more difficult to interpret. However, long-term outcomes of physical and psychological factors, functional status, and social interactions are becoming more and more important both for physicians and nurses as well as for patients and their relatives [7, 8]. The ideal outcome is that ICU patients will attain their pre-morbid, or a better or similar, quality of life as a person of the same age, gender, and co-morbidity [9]. This bears the question in which period this recovery should occur. Indeed, optimal HRQOL follow-up periods are not defined in addition to the lack of knowledge regarding the optimal observation period for HRQOL preceding ICU stay. Most of the HRQOL studies performed in general ICU patients after ICU admission did not exceed a follow-up period of 2 years. Only five studies had a longer follow-up, but did not measure pre-morbid HRQOL [4, 10–12], except for the study by Cuthbertson et al. [13].

Therefore, the aim of our study was to measure HRQOL before ICU admission and to assess the impact of ICU stay by following the recovery of HRQOL in surviving patients from ICU admission up to 5 years after ICU discharge. In addition we compared the HRQOL of the surviving patients with an age-matched general population.

We hypothesized that HRQOL improves over a prolonged period following ICU discharge to a level comparable to an age-matched general population.

Materials and methods

We performed a long-term prospective cohort study in a 10-bed closed-format (intensives-led) mixed medical-surgical ICU of the Gelre Hospital, a 654-bed university-affiliated teaching hospital in Apeldoorn, the Netherlands. Between September 2000 until January 2007 all admissions were screened for study participation (ESM-1). The local ethics committee approved the study. Informed consent was given by a proxy and as soon as possible by the patients themselves. We evaluated HRQOL before admission (proxies), at ICU discharge, hospital discharge, and 1, 2, and 5 years after ICU discharge. We only included patients with an ICU stay longer than 48 h, because we aimed to evaluate the sickest patients, hypothesizing that the impact of ICU stay on HRQOL would be most prominent in those cases. Patients with an impaired level of self-awareness or without the ability to communicate adequately at any time during the study were excluded. Patients’ demographic data and severity of illness (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, APACHE II) [14] were also collected.

Health-related quality of life measurement

The Short-Form 36 (SF-36 version 1) [15], a widely used standardized generic health status questionnaire, was used to measure HRQOL. This measurement contains eight multi-item dimensions, i.e., physical functioning (PF), role limitation due to physical problems (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role limitation due to emotional problems (RE), and mental health (MH). Computation of domain scores was performed according to predefined guidelines [16]. Higher scores represent better functioning, with a range from 0 to 100. Furthermore, scores were aggregated to summary measures representing a physical health summary score (physical component score (PCS), mainly reflecting physical functioning, physical role, pain, and general health) and a mental health summary score (mental component score (MCS), mainly reflecting vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health) [17]. Population scores on PCS and MCS have been standardized on a population mean of 50 with a standard deviation of 10 [18]. The SF-36 was used for assessing HRQOL following critical illness [19, 20]. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch-language version of the SF-36 health questionnaire were evaluated in 1998 in community and chronic disease populations [21, 22].

As most of the patients are not able to complete a questionnaire at the time of admission, proxies have to be used frequently as a surrogate approach. The use of proxies to assess the patients HRQOL was validated in earlier studies by our research group using the SF-36 [23] and the Academic Medical Center Linear Disability Score (ALDS) measuring physical reserve [24], and showed that on all dimensions a significant correlation was found between the patient and their proxy. In general proxies tended to underestimate the patients’ quality of life, although the differences were small (less than 5 %). Proxies had to be in close contact with the patient on a regular basis. Proxies were asked to answer on behalf of the patient and mark the statement that best described the patient’s state of health in the last 4 weeks prior to the admission.

The first SF-36 questionnaire was completed within 48 h of admission, using the standard time frame of 4 weeks preceding critical illness. At the time of ICU discharge and hospital discharge, the patients were specifically asked to score their HRQOL according to their current situation. During hospital admission, patients completed the questionnaire by personal interview. All interviews were performed by the same investigator (JH). After hospital discharge, the questionnaire was completed by personal interview or conducted by phone. When needed, the investigator (JH) visited the patients at home. The average time required to complete the questionnaire was 15–20 min. Furthermore, we compared HRQOL before ICU admission and 5 years after ICU discharge with those of an age-matched general Dutch population [22] and used the first question of the SF-36 as a measure of the perceived overall health state. This is the single-item question pertaining to general status: “In general would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”

Statistical analysis

To correct for the gradual deterioration of HRQOL due to ageing in the general population, we calculated the natural decline of the Dutch normal population [22] as follows. In view of the average age of the study population [25], values for the different domains in the general population in the stratum 65–70 years of age were compared to those in the stratum 60–65 years of age. We calculated the perceptual decline for every SF-36 domain and applied these values to the scores obtained 5 years after ICU discharge to get the corrected HRQOL values used in final analysis.

As we aimed to assess how patients improve after ICU discharge, we chose to analyze changes over time from ICU discharge using a linear mixed model for each dimension of the SF-36 using the pre-ICU score as a covariate [26]. The main advantage of such a model is that each measurement of each subject is used, regardless of time of drop-out (like mortality). These models are less biased than complete-case analyses, as also the ‘worse’ patients who eventually drop out of the study are included as much as possible in the estimations of change over time. Including also patients who drop out will have a negative impact on the estimates of improvement over time. The improvement from ICU discharge is estimated using data obtained directly from patients; the proxy assessment is used only to correct for differences in pre-ICU HRQOL between patients. We made the following technical choices in the linear mixed model: a random intercept model, in which patients were included as a random effect (i.e., allowed to deviate from the common intercept); fixed effects included time, pre-ICU HRQOL score, APACHE II score, age, and gender; and the final estimation method was restricted maximum likelihood. The assumption of normality of the residuals was assessed by a Q–Q plot. Estimates of domain scores at different time points are presented with 95 % confidence intervals. To present the simplest possible model, we tested whether random slopes needed to be included in the model. We chose to report the models with random slopes for time (i.e., a different slope/trajectory for each patient), as these were significantly better than models without random slopes in all domains.

For the comparison of pre-admission versus 5 years, we could not use the linear mixed model, as the pre-admission score was included in that model as a covariate. Therefore, we performed analyses of covariance (ANCOVA, i.e., a general linear model) with Bonferroni correction (significance level, p < 0.05) to detect differences in the SF-36 scores at admission between survivors and non-survivors and to assess changes between pre-ICU and 5 years after ICU discharge (repeated measures ANCOVA). Statistical adjustment was made for age, sex, and APACHE II score by including these variables as covariates.

SF-36 dimensions of survivors were compared with normative data from the age group 60–70 years from the Dutch normal population [22] using the one sample T test. The significance level was adjusted by Bonferroni correction according to the number of related tests conducted. To examine the relative magnitude of changes over time and between groups, we used effect sizes based on the mean change found in a variable divided by the baseline standard deviation. Effect sizes estimate whether particular changes/differences in health status are relevant, helping one to interpret mean differences. Following Cohen, effect sizes of at least 0.20, at least 0.50, and greater than 0.80 were considered small, medium, and large changes, respectively [27]. To illustrate the course of HRQOL over time, we plotted raw (uncorrected) data. Groups were defined on the basis of the length of follow-up (i.e., ranging from only pre-ICU to 5 years after discharge).

χ 2 tests were used to assess the demographic differences between ICU survivors and ICU non-survivors. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL, USA, version 17). All data are expressed as mean ± SD where appropriate unless otherwise indicated.

Results

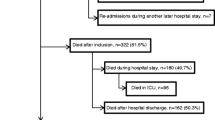

During the study period, 3,775 patients were screened for study participation. We included a total of 749 patients (20 %) (ESM-1). Out of those patients 61 % were men and 39 % women. Baseline HRQOL was obtained from all patients who were evaluated in the final analysis. HRQOL was measured at 1 year after ICU discharge (n = 378), at 2 years after ICU discharge (n = 301), and 5 years after ICU discharge (n = 234). At 5 years, a total of 115 patients (15 %) were lost to follow-up (mental impairment, dementia, long-term delirium). Five-year mortality of the total group was 53.4 % (n = 400). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients lost to follow-up did not differ significantly from the group analyzed in the study except for some types of admission and diagnostic groups (ESM-2). The demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients are shown in Table 1.

Changes over time in patients up to 5 years after ICU discharge

Most SF-36 dimensions changed significantly over time from ICU discharge, except for bodily pain (ESM-3 and Fig. 1). Pre-ICU HRQOL score was a significant predictor of change, in contrast to the APACHE II score. At ICU discharge, HRQOL scores were lowest for the physical functioning, role-physical, and general health dimensions. Surprisingly, bodily pain had a high (i.e., positive) score. Inspection of the Q–Q plots showed that the residuals of the models for all dimensions were normally distributed (ESM-3). The course of HRQOL over time is illustrated in Fig. 2 using uncorrected values, i.e., not derived from the linear mixed model.

Comparisons of survivors before ICU admission, 5 years after ICU discharge, and the general population. PF physical functioning, RP role limitation due to physical problems, BP bodily pain, GH general health, VT vitality, SF social functioning, RE role limitation due to emotional problems, MH mental health

Comparison of HRQOL of survivors with general population

Among those who survived 5 years, the pre-admission HRQOL was significantly lower in two dimensions, i.e., vitality (p < 0.001) and mental health (p < 0.001), compared with an age-matched general population. The effect sizes were small for both vitality (0.32) and mental health (0.26). The significant difference of the bodily pain dimension was based on a higher pre-admission score (mean 82.0) compared with the general population (mean 70.5) (Table 2). At 5 years, after correction for natural decline, the HRQOL was significantly lower than values in the general population in almost all dimensions except role-emotional (Table 2, p = 0.24), with medium effect sizes in the general health (0.61), role-physical (0.60), and the physical functioning (0.58) domains. Effect sizes in all other domains were small (<0.50). The significant difference of the bodily pain dimension was based on a higher mean 5-year score (mean 77.4) compared with the general population (mean 70.5) (Table 2).

Comparison of pre-admission HRQOL with 5 years after ICU discharge of survivors

After correction for natural decline in HRQOL, the mean scores of four dimensions—physical functioning (p < 0.001), role-physical (p < 0.001), general health (p < 0.001), and social functioning (p = 0.003)—were still significantly lower 5 years after ICU discharges compared with their pre-admission levels (n = 242). However, effect sizes were small (<0.5) in all these four dimensions (Table 2). Original obtained values before correction for natural decline in HRQOL are available (Table 3).

Comparison of pre-admission HRQOL survivors with non-survivors

Pre-admission HRQOL of non-survivors was significantly lower in all dimensions compared with the 5-year survivors (all p < 0.001, except bodily pain; p = 0.007) (ESM-4).

Discussion

This is the first prospective cohort study in critically ill survivors evaluating long-term effects of ICU stay on HRQOL taking pre-morbid HRQOL levels and effects of natural decline into account. We repeatedly measured changes in HRQOL from ICU discharge to 5 years thereafter. Improvement was strongest in the domains physical health and role-physical, and intermediate in vitality and social functioning domains. The smallest improvements were seen in bodily pain and mental health. We found at 5 years, after correcting for natural decline, that the HRQOL had decreased significantly and was still significantly lower in the physical functioning, social functioning, and general health dimensions compared with an age-matched general population. However, the effect size of the decreased HRQOL was small in all domains.

The number of studies that report follow-up in a general group of ICU patients for 5 years or longer [4, 10, 11, 13] is scarce. One of the goals of our long-term follow-up study was to measure how much HRQOL had changed over time. However, how “long” is a long-term outcome? The most important problem of long-term follow-up is that more and more patients will be lost to follow-up, which can bias the results as the sickest patients drop out earlier [25, 28–30]. In our study, the loss of follow-up due to not responding 1–5 years after discharge was small, because we made every effort to target the highest response rate possible and all available data were used in the linear mixed model. This minimizes the influence of the survivors on the estimates of improvement, i.e., the estimates are less positive. A major proportion of our patients died before completing the 5-year survey. The overall mortality rate of our study was 53.4 % at 5 years after ICU discharge, which is somewhat higher compared to that found by Stricker et al. [11], who observed a 9-year mortality rate of 47.5 % despite a relatively low severity of illness and short ICU stay. This difference is not surprising because only patients with an ICU stay longer than 48 h were included in our study. The studies by Flaatten, Kaarlola, and others [4–10] showed a high mortality rate early after ICU discharge. These differences in survival may be due to differences in case mix. When comparing the 5-year HRQOL, corrected for natural decline, with the pre-admission HRQOL in our study especially the physical functioning dimensions (physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, and general health) were significantly lower compared with their pre-admission levels. However, the effect size of the decreased HRQOL was small, suggesting that the effect of the ICU admission on perceived HRQOL after 5 years may not be clinically relevant. Effect size is the degree to which the findings have practical significance in our study population [27]. It should be noted that these effect sizes are about the survivors: patients who drop out earlier have worse scores both before and after ICU compared to patients who drop out later or who survive. Imputing scores for patients who dropped out (i.e., died) would have a marked impact on the effect sizes. We did not impute missing scores, as we were interested in the HRQOL of survivors. The low HRQOL scores in the physical domains are in keeping with the findings in studies of general ICU patients [13, 31] as well as in studies of ARDS patients 5 years after ICU discharge [12, 13, 32]. We also compared our study results with a general population, and compared the long-term HRQOL of patients at 5 years with HRQOL before ICU admission. At 5 years, HRQOL corrected for natural decline was significantly lower in almost all dimensions compared with a general population. This is in line with the results of the study by Cuthbertson et al. [13] using the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D). Interestingly, Berkius et al. [33] found that at 2 years after ICU discharge, HRQOL in patients with COPD was similar to that in patients with COPD who had not received ICU treatment. In line with this study, others concluded recently that HRQOL scores after adjusting for age, sex, and coexisting conditions were almost equal to those of the normal population at 6 months after ICU discharge [33, 34]. To our knowledge scarce information exists regarding the natural progression of HRQOL in ICU patients over time, for instance due to aging. Hopman et al. [35] studied the natural progression of HRQOL over time in a normative population and found that mean changes tended to be small, but there was an overall trend towards decreasing HRQOL over time. Changes were more pronounced in the older age groups and in the physical domains. Additionally, natural decline is to our knowledge only studied in normative populations and therefore cannot be generalized to other populations. Interestingly, in our study, after correction of natural decline, the physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, and general health dimensions remained significantly lower compared with their pre-admission levels. However the effect sizes were smaller, suggesting that the effect of the ICU admission on perceived quality of life after 5 years in survivors was small and may not be clinically relevant. The use of Cohen’s effect size method to get an idea about the potential relevance of the findings was used in our earlier HRQOL study in critically ill patients [25] using SF-36, but has also been used in other HRQOL research [36]. Additionally, 6–12 months after ICU discharge, HRQOL dimensions were relatively stable except for the physical and role-physical dimensions, suggesting that these time points are less important when measuring HRQOL. The domain role-physical is related to physical functioning within the home environment. Given the low scores at 5 years, future research could be directed to amendable factors that influence physical functioning within the home setting.

In view of the strong effects in the physical domains, attention should be paid to early mobilization to potentially prevent or decrease the rapid loss of physical reserve during ICU stay and consequently result in more rapid recovery of HRQOL. Indeed, these kinds of interventions have been shown to improve outcome measures in ICU patients [37].

Several limitations to our study should be mentioned. First, we only included patients on their first admission [25] who also stayed in the ICU for more than 48 h. Therefore, the results are not generalizable to the group of patients with a short ICU stay. Second, as mentioned above, we chose to use proxies for pre-admission scores, instead of a retrospective assessment at ICU discharge. This was done because the critical illness may influence the patients’ recollection of their previous health and the approach of using proxies in this setting [23] was validated in an earlier study by our group and by other studies [19, 38]. It is known that proxies may differ in their assessment from patients themselves, but our earlier results showed that these differences were small in our experienced research setting. Concerns about proxy estimations of HRQOL in populations with high disease severity [39] are probably based on major differences in timing of assessments of HRQOL: interviewing patients 3 months after ICU discharge and their proxies at study entry. It is likely that the critical illness may influence the patients’ retrospective recollection of their previous health (recall bias) and that they may overestimate their previous health. Still, the results between proxy and ICU patient measures should be interpreted with caution. Third, the presence of delirium could have influenced the response. Although structural screening for the presence of delirium was not performed at the time the study was started, we still tried to identify delirious patients by asking the opinions of the nurses, doctors involved in daily care of the patients, and included information from close relatives as well. The patients suspected of delirious states or other incapacities were excluded from the study. Finally, we cannot rule out that response shift played a role in our study population, i.e., the change in self-evaluation resulting from changes in internal standards or values in patients confronted with a life-threatening disease or chronic incurable disease [40]. Social functioning for instance could be perceived differently in the clinical setting because of the many visitors in the hospital.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that 5 years after ICU discharge, after correction for natural decline, the effect size of a decreased HRQOL was small in all study domains, suggesting that the effect of the ICU admission on perceived HRQOL after 5 years may not be clinically relevant.

Abbreviations

- APACHE II:

-

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

- BP:

-

Bodily pain

- CAM-ICU:

-

Confusion assessment method for the ICU

- EQ-5D:

-

EuroQol-5-D

- GH:

-

General health

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range (P 25–P 75)

- LOS:

-

Length of stay

- MCS:

-

Mental component score

- MH:

-

Mental health

- PCS:

-

Physical component score

- PF:

-

Physical functioning

- RE:

-

Role limitation due to emotional problems

- RP:

-

Role limitation due to physical problems

- SF:

-

Social functioning

- SF-36:

-

Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form

- VT:

-

Vitality

References

Combes A, Costa MA, Trouillet JL, Baudot J, Mokhtari M, Gilbert C et al (2003) Morbidity, mortality, and quality-of-life outcomes of patients requiring > or = 14 days of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 31:1373–1381

Cuthbertson BH, Scott J, Strachan M, Kilonzo M, Vale L (2005) Quality of life before and after intensive care. Anaesthesia 60:332–339

Eddleston JM, White P, Guthrie E (2000) Survival, morbidity, and quality of life after discharge from intensive care. Crit Care Med 28:2293–2299

Flaatten H, Kvale R (2001) Survival and quality of life 12 years after ICU. A comparison with the general Norwegian population. Intensive Care Med 27:1005–1011

Niskanen M, Ruokonen E, Takala J, Rissanen P, Kari A (1999) Quality of life after prolonged intensive care. Crit Care Med 27:1132–1139

Ridley SA, Chrispin PS, Scotton H, Rogers J, Lloyd D (1997) Changes in quality of life after intensive care: comparison with normal data. Anaesthesia 52:195–202

Graf J, Koch M, Dujardin R, Kersten A, Janssens U (2003) Health-related quality of life before, 1 month after, and 9 months after intensive care in medical cardiovascular and pulmonary patients. Crit Care Med 31:2163–2169

Wu A, Gao F (2004) Long-term outcomes in survivors from critical illness. Anaesthesia 59:1049–1052

Black NA, Jenkinson C, Hayes JA, Young D, Vella K, Rowan KM et al (2001) Review of outcome measures used in adult critical care. Crit Care Med 29:2119–2124

Kaarlola A, Pettila V, Kekki P (2003) Quality of life six years after intensive care. Intensive Care Med 29:1294–1299

Stricker KH, Sailer S, Uehlinger DE, Rothen HU, Zuercher Zenklusen RM, Frick S (2011) Quality of life 9 years after an intensive care unit stay: a long-term outcome study. J Crit Care 26:379–387

Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Diaz Granados N, Cooper A et al (2011) Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 364:1293–1304

Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, Maclennan G, Vale L (2010) Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care 14:R6

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE (1985) APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 13:818–829

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473–483

Ware JE (1993) Health survey manual and interpretation guide. Medical Outcomes Trust, Boston

Ware JE, Kosinski M (2001) Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res 10:405–413

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’ Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T et al (1992) Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 305:160–164

Chrispin PS, Scotton H, Rogers J, Lloyd D, Ridley SA (1997) Short Form 36 in the intensive care unit: assessment of acceptability, reliability and validity of the questionnaire. Anaesthesia 52:15–23

Heyland DK, Hopman W, Coo H, Tranmer J, McColl MA (2000) Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of sepsis. Short Form 36: a valid and reliable measure of health-related quality of life. Crit Care Med 28:3599–3605

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L (1993) Short Form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age. BMJ 306:1437–1440

Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman MA et al (1998) Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 health survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 51:1055–1068

Hofhuis J, Hautvast JL, Schrijvers AJ, Bakker J (2003) Quality of life on admission to the intensive care: can we query the relatives? Intensive Care Med 29:974–979

Hofhuis JG, Dijkgraaf MG, Hovingh A, Braam R, van de Braak L, Spronk PE, et al (2011) The Academic Medical Center Linear Disability Score for evaluation of physical reserve on admission to the ICU: can we query the relatives? Crit Care 15:R212

Hofhuis JG, Spronk PE, van Stel HF, Schrijvers GJ, Rommes JH, Bakker J (2008) The impact of critical illness on perceived health-related quality of life during ICU treatment, hospital stay, and after hospital discharge: a long-term follow-up study. Chest 133:377–385

Twisk, Jos WR (2003) Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology. Cambridge University, UK

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, NJ

Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD, Annemans L, Decruyenaere JM (2010) Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med 38:2386–2400

Hofhuis JG, Spronk PE, van Stel HF, Schrijvers AJ, Bakker J (2007) Quality of life before intensive care admission is a predictor of survival. Crit Care 11(4):R78

Nesseler N, Defontaine A, Launey Y, Morcet J, Malledant Y, Seguin P (2013) Long-term mortality and quality of life after septic shock: a follow-up observational study. Intensive Care Med 39:881–888

Jones C (2013) What’s new on the post-ICU burden for patients and relatives? Intensive Care Med 10:1832–1835

Schelling G, Stoll C, Vogelmeier C, Hummel T, Behr J, Kapfhammer HP et al (2000) Pulmonary function and health-related quality of life in a sample of long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 26:1304–1311

Berkius J, Engerstrom L, Orwelius L, Nordlund P, Sjoberg F, Fredrikson M et al (2013) A prospective longitudinal multicentre study of health related quality of life in ICU survivors with COPD. Crit Care 17:R211

Orwelius L, Fredrikson M, Kristenson M, Walther S, Sjoberg F (2013) Health-related quality of life scores after intensive care are almost equal to those of the normal population: a multicenter observational study. Crit Care 17:R236

Hopman WM, Berger C, Joseph L, Towheed T, VandenKerkhof E, Anastassiades T et al (2006) The natural progression of health-related quality of life: results of a five-year prospective study of SF-36 scores in a normative population. Qual Life Res 15:527–536

Skinner EH, Warrillow S, Denehy L (2011) Health- related quality of life in Australian survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med 39:1896–1905

Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL et al (2009) Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 373:1874–1882

Rogers J, Ridley S, Chrispin P, Scotton H, Lloyd D (1997) Reliability of the next of kins’ estimates of critically ill patients’ quality of life. Anaesthesia 52:1137–1143

Scales DC, Tansey CM, Matte A, Herridge MS (2006) Difference in reported pre-morbid health-related quality of life between ARDS survivors and their substitute decision makers. Intensive Care Med 32:1826–1831

Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE (1999) Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med 48:1507–1515

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Take home message: After correction for natural decline, the effect sizes of decreases in HRQOL were small, suggesting that patients regain their age specific HRQOL 5 years after their ICU stay.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hofhuis, J.G.M., van Stel, H.F., Schrijvers, A.J.P. et al. ICU survivors show no decline in health-related quality of life after 5 years. Intensive Care Med 41, 495–504 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3669-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3669-5