Abstract

Objectives

To quantify the strength of association between passive and active forms of screen time and adolescent major depressive episode and anxiety disorders.

Methods

Data from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study, a representative sample of 2,320 adolescents aged 12–17 years in Ontario (mean age = 14.58, male = 50.7%) were used. Screen time was measured using adolescent self-report on time spent on screen-based activities. Past 6-month occurrence of DSM-IV-TR defined major depressive episode, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and specific phobia which were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents.

Result

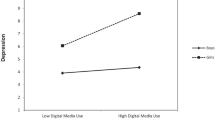

Adolescents reporting 4 or more hours of passive screen time per day, compared to those reporting less than 2 h, were three times more likely to meet the DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depressive episode [OR = 3.28(95% CI = 1.71–6.28)], social phobia [OR = 3.15 (95% CI = 1.57–6.30)] and generalized anxiety disorder [OR = 2.92 (95% CI = 1.64–5.20)]. Passive screen time continued to be significantly associated with increased odds of disorders, after adjusting for age, sex, low income, active screen time use, sleep and physical activity. A small-to-moderate attenuation of the estimated ORs was observed in the fully adjusted model. In contrast, associations between active screen time use and depression and anxiety disorders were smaller in magnitude and failed to reach statistical significance.

Conclusions

Passive screen time use was associated with mood and anxiety disorders, whereas active screen time was not. Further research is needed to better understand the underlying processes contributing to differential risk associated with passive versus active screen time use and adolescent mood and anxiety disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kessler RC et al (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(6):593–602

Polanczyk GV et al (2015) Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(3):345–365

Georgiades K, Duncan L, Wang L, Comeau J, Boyle MH, 2014 Ontario Child Health Study Team (2019) Six-month prevalence of mental disorders and service contacts among children and youth in Ontario: evidence from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. Can J Psychiatry 64(4):246–255

Comeau J, Georgiades K, Duncan L, Wang L, Boyle MH, 2014 Ontario Child Health Study Team (2019) Changes in the prevalence of child and youth mental disorders and perceived need for professional help between 1983 and 2014: evidence from the Ontario child health study. Can J Psychiatry 64(4):256–264

Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B (2016) National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 138(6):e20161878. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1878

Twenge JM, Martin GN, Campbell WK (2018) Decreases in psychological well-being among american adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Emotion 18(6):765–780

Owen N et al (2010) Sedentary behavior: emerging evidence for a new health risk. Mayo Clin Proc 85(12):1138–1141

Atkin AJ et al (2014) Prevalence and correlates of screen time in youth: an international perspective. Am J Prev Med 47(6):803–807

Sigman A (2012) Time for a view on screen time. Arch Dis Child 97(11):935–942

Hoare E et al (2016) The associations between sedentary behaviour and mental health among adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 13(1):108

Stiglic N, Viner RM (2019) Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: a systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 9(1):e023191

Sweetser P et al (2012) Active versus passive screen time for young children. Australas J Early Child 37(4):94–98

Martinez-Gomez D et al (2009) Associations between sedentary behavior and blood pressure in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 163(8):724–730

Wang X, Perry AC (2006) Metabolic and physiologic responses to video game play in 7-to 10-year-old boys. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160(4):411–415

Orben A (2020) Teenagers, screens and social media: a narrative review of reviews and key studies. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4

Boers E et al (2019) Association of screen time and depression in adolescence. JAMA Pediatr 173(9):853–859

Sanders T et al (2019) Type of screen time moderates effects on outcomes in 4013 children: evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16(1):117

Wu X et al (2013) Prevalence and factors of addictive Internet use among adolescents in Wuhan, China: interactions of parental relationship with age and hyperactivity-impulsivity. PLoS ONE 8(4):e61782

Hayward J et al (2016) Lifestyle factors and adolescent depressive symptomatology: associations and effect sizes of diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 50(11):1064–1073

Houghton S et al (2018) Reciprocal relationships between trajectories of depressive symptoms and screen media use during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 47(11):2453–2467

Twenge JM, Campbell WK (2018) Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev Med Rep 12:271–283

Martins N, Harrison K (2012) Racial and gender differences in the relationship between children’s television use and self-esteem: A longitudinal panel study. Commun Res 39(3):338–357

Domingues-Montanari S (2017) Clinical and psychological effects of excessive screen time on children. J Paediatr Child Health 53(4):333–338

Costigan SA et al (2013) The health indicators associated with screen-based sedentary behavior among adolescent girls: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health 52(4):382–392

Vernon L, Modecki KL, Barber BL (2018) Mobile phones in the bedroom: Trajectories of sleep habits and subsequent adolescent psychosocial development. Child Dev 89(1):66–77

Woods HC, Scott H (2016) # Sleepyteens: social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J Adolesc 51:41–49

Twenge JM, Martin GN, Spitzberg BH (2019) Trends in US Adolescents’ media use, 1976–2016: The rise of digital media, the decline of TV, and the (near) demise of print. Psychol Pop Media Culture 8(4):329

Twenge JM (2020) Why increases in adolescent depression may be linked to the technological environment. Curr Opin Psychol 32:89–94

Twenge JM (2019) More time on technology, less happiness? Associations between digital-media use and psychological well-being. Curr Direct Psychol Sci 28(4):372–379

Hysing M et al (2015) Sleep and use of electronic devices in adolescence: results from a large population-based study. BMJ Open 5(1):e006748

Vallance JK et al (2015) Associations of overall sedentary time and screen time with sleep outcomes. Am J Health Behav 39(1):62–67

Hale L, Guan S (2015) Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Sleep Med Rev 21:50–58

Twenge JM, Krizan Z, Hisler G (2017) Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among US adolescents 2009–2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Med 39:47–53

Twenge JM (2018) Amount of time online is problematic if it displaces face-to-face social interaction and sleep. Clin Psychol Sci 6(4):456–457

Przybylski AK (2018) Digital screen time and pediatric sleep: evidence from a preregistered cohort study. J Pediatr 205:218–223

Falbe J et al (2015) Sleep duration, restfulness, and screens in the sleep environment. Pediatrics 135(2):e367–e375

Melkevik O et al (2010) Is spending time in screen-based sedentary behaviors associated with less physical activity: a cross national investigation. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 7(1):46

Lautenschlager NT et al (2008) Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA 300(9):1027–1037

Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC (2000) A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32(5):963–975

Barlett ND et al (2012) Sleep as a Mediator of Screen Time Effects on US Children's Health Outcomes. J Child Media 6(1):37–50

Herman KM, Hopman WM, Sabiston CM (2015) Physical activity, screen time and self-rated health and mental health in Canadian adolescents. Prev Med 73:112–116

Feng Q et al (2014) Associations of physical activity, screen time with depression, anxiety and sleep quality among Chinese college freshmen. PLoS ONE 9(6):e100914

Wu X et al (2015) Low physical activity and high screen time can increase the risks of mental health problems and poor sleep quality among Chinese college students. PLoS ONE 10(3):e0119607

Wang J-L et al (2018) The reciprocal relationship between passive social networking site (SNS) usage and users’ subjective well-being. Soc Sci Computer Rev 36(5):511–522

Orben A, Przybylski AK (2019) The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nat Hum Behav 3(2):173

Statistics Canada (2017) Microdata user guide 2014 Ontario Child Health Study

Boyle MH, Georgiades K, Duncan L, Comeau J, Wang L, 2014 Ontario Child Health Study Team (2019) The 2014 Ontario Child Health Study—methodology. Can J Psychiatry 64(4):237–245

Tremblay MS et al (2016) Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 41(6):S311–S327

Buysse DJ et al (1989) The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213

Sheehan DV et al (2010) Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID). J Clin Psychiatry 71(3):313–326

Duncan L et al (2017) Psychometric evaluation of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). Psychol Assess 30(7):916–928. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000541

StataCorp S (2018) Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP

Twenge JM et al (2018) Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychol Sci 6(1):3–17

Jelenchick LA, Eickhoff JC, Moreno MA (2013) “Facebook depression?” Social networking site use and depression in older adolescents. J Adolesc Health 52(1):128–130

Fox KR (1999) The influence of physical activity on mental well-being. Public Health Nutr 2(3a):411–418

Skelly AC, Dettori JR, Brodt ED (2012) Assessing bias: the importance of considering confounding. Evid Spine-Care J 3(01):9–12

Kleinbaum DG et al (1988) Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods, vol 601. Duxbury Press Belmont, CA

Kraut R et al (1998) Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am Psychol 53(9):1017

Twenge JM, Spitzberg BH, Campbell WK (2019) Less in-person social interaction with peers among US adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. J Soc Pers Relatsh 36(6):1892–1913

Strasburger VC et al (2013) Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics 132(5):958–961

Tremblay MS et al (2016) Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 41(6 Suppl 3):S311–S327

Lenhart A et al. (2010) Social Media & Mobile Internet Use among Teens and Young Adults. Millennials. Pew Internet and American life project

Mark AE, Boyce WF, Janssen I (2006) Television viewing, computer use and total screen time in Canadian youth. Paediatr Child Health 11(9):595–599

Leatherdale S, Ahmed R (2011) Screen-based sedentary behaviours among a nationally representative sample of youth: are Canadian kids couch potatoes. Chronic Dis Inj Can 31(4):141–146

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Favotto, L., Halladay, J. et al. Differential associations between passive and active forms of screen time and adolescent mood and anxiety disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55, 1469–1478 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01833-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01833-9